It was two years before the first Earth Day in 1970 when Garrett Hardin penned the famous essay “The Tragedy of the Commons,” and it fit a certain bleak and despairing mood of the time. Paul Ehrlich had just published The Population Bomb, a Malthusian account of a world overwhelmed by sheer numbers of people. Against the backdrop of that gloom, Hardin’s theory came as another dose of bad news, “proving” that we also had no hope of controlling our appetite for natural resources. Because no one owned the oceans or the atmosphere, we would inevitably fish and pollute them into oblivion. Hardin offered a few suggestions, but his title summed it up: we were witnessing a tragedy whose script could not be revised.

Oddly, a decade later, his argument fit just as easily the exuberant, privatizing mood of the Reagan years. No one owns the sky or the sea? Well, then, let’s sell them! The race was on to privatize everything, from fishing rights to kids’ playgrounds, on the theory that this was the only way to manage them well. Society was the problem, the individual was the solution.

The only thing that Hardin’s argument didn’t fit was the facts, at least not all of them. For eons communities had managed to protect all kinds of resources without private ownership. In America and in England, it’s true, a couple of centuries of enclosure and corporatization made this harder to recall. But around the world, most of the pasture lands, forests, and streams had long been controlled by communities, drawing on deep traditions of custom and collective wisdom. Even in the United States, we had classic examples—the acequia irrigation systems of New Mexico, which may be the only sustainable water systems in the American West, or the lobster fishery of Maine, protected from overfishing less by law than by long custom.

And in the years since “The Tragedy of the Commons” appeared, even a cursory glance around the landscape reveals that Hardin’s gloom has been disproven a thousand times. For example, I’m willing to bet that many of the people reading this turned on their local public radio station this morning. Here’s how public radio works: give away your product for free with no advertising, and then twice a year wheedle people to make a donation to pay for it. Turn that in as your business plan at some bank and they’ll laugh you out the door, but public radio has been the fastest-growing sector of the broadcast industry for years. And now we have low-power FM and community radio, not to mention the explosion of free content on the Internet.

The last few decades have been dominated by the premise that privatizing all economic resources will produce endless riches. Which was kind of true, except that the riches went to only a few people.

I’ve spent most of my life as a writer—and one of the sweetest parts of that job is knowing that whatever I produce ends up in a library, an institution dedicated to the idea that we can share things easily. There are innumerable other examples—and they are the parts of our lives that we usually care most about. They don’t show up on balance sheets because they’re not producing profit, but they are producing satisfaction.

These things we share are called commons, which simply means they belong to all of us. Commons can be gifts of nature—such as fresh water, wilderness, and the airwaves—or the products of social ingenuity, like the Internet, parks, artistic traditions, or the public health service. But today much of our common wealth is under threat from those hungry to ruin it or take it over for selfish, private purposes.

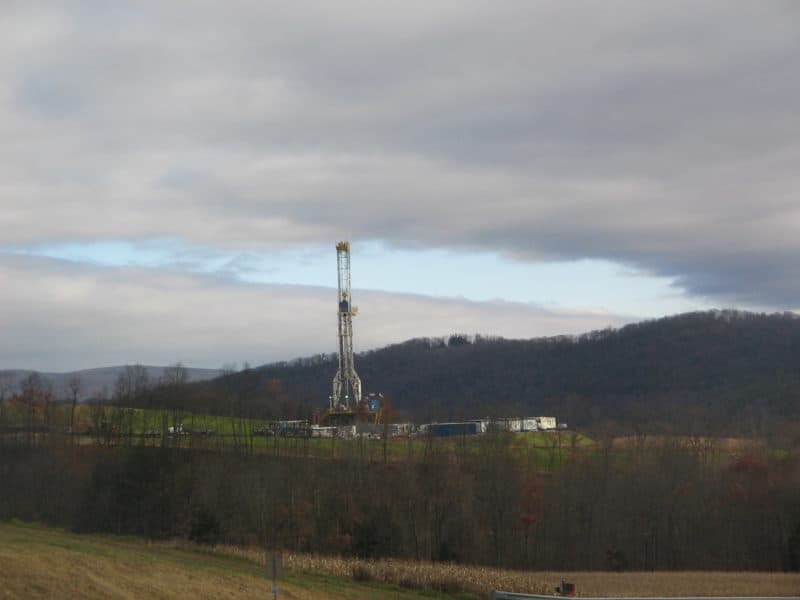

The most crucial commons, perhaps, is the one now under greatest siege, and it poses a test of whether we can pull together to solve our deepest problems or succumb to disaster. Our atmosphere has been de facto privatized for a long time now—we’ve allowed coal, oil, and gas interests to own the sky, filling it with the carbon that is the inevitable byproduct of their business. For a couple of centuries, this seemed mostly harmless—CO2 didn’t seem to be causing much trouble. But two decades ago, we started to understand the effects of global warming, and now each month, the big scientific journals bring us new proof of just how vast the damage is: the Arctic is melting, Australia has been on fire, the pH of the ocean is dropping fast.

If we are to somehow ward off the coming catastrophes, we have to reclaim this atmospheric commons. We have to figure out how to cooperatively own and protect the single most important feature of the planet we inhabit—the thin envelope of atmosphere that makes our lives possible. Wrestling this key prize away from ExxonMobil and other corporations is the great political issue of our time, and some of the solutions proposed have been ingenious—most notably the idea put forth by commons theorist Peter Barnes and others that we should own the sky jointly and share in the profits realized by leasing its storage space to the fossil fuel industry. For that to work, of course, we would have to reduce that storage space quickly and dramatically. Barnes’s cap-and-dividend plan offers one way to make that economically and politically feasible.

But for this and other necessary projects to succeed, we need first to break the intellectual spell under which we live. The last few decades have been dominated by the premise that privatizing all economic resources will produce endless riches. Which was kind of true, except that the riches went to only a few people. And in the process they melted the Arctic, as well as dramatically increasing inequality around the world.

The commons is a crucial part of the human story that must be recovered if we are to deal with the problems now crowding in on us. This story is equal parts enlightening and encouraging, and it is entirely necessary for us to hear it.

This post originally appeared at OnTheCommons.org.