The Colbert Report offices are two blocks from Piers 92 and 94, which this past weekend seemed an apt geographic coincidence after the Armory Show moved in. There’s not much that’s very civilized or sensical about contemporary art fairs, at least not these days: The spiky, brightly-colored, confrontational artworks on display; the fashionable dealers who, in a few cases, have a by-now-clichéd bottle of iced champagne alongside the binders of images on their desks; the cloud of overwhelmed uselessness that seems to surround many fair-goers’ heads. Kind of like the breathless conservatives who claim Stephen Colbert as champion, some fairgoers seemed dizzily unaware of what’s going on around them.

Colbert’s sights may be elsewhere, but the cognitive dissonance of today’s “art world” has inspired the Occupy Museums movement to protest its excesses outside of the MoMA and now the Armory Show. The “mobile exchange art fair” that Occupy Museums announced on its Facebook page, which took place on Saturday and Sunday, invited participants to “bring items such as paintings, drawings, sculpture, conceptual art, crafts, food, and other objects to exchange with Armory attendees and each other.” Because,they say, “The wealthiest 1 percent exploit our art and culture for their personal gain. Artists and art-lovers are left wanting.” Certain tableaux at the fair might have seemed to confirm that sentiment.

There was a tonal difference between the two Armory fairs, Modern and Contemporary. At Modern, in the small Pier 92, the ceilings were low and you can see the Hudson out of windows on either side of the strip of galleries along the slim aisle. It was quite calm, with Picassos and kinetic art and an enormous splotch sculpture by Sol LeWitt. The contemporary fair was in a cavernous industrial-ish space that was echoey and bright. The colors were suddenly fluorescent and jumped off the page, and objects that defy simple understanding or aesthetic pleasure were given place of pride in booths.

There was a framed take-out container stained with oil at the challenging booth of Galleria Continua, which also has the enormous mirror, rectangular but for a small chunk taken from a bottom corner, in front of which groups of teens stand to take self-portraits on their camera phones. Skeptics make snide comments. There was a Baldessari photo series with dots over the faces of dead people crushed by urban detritus, and, like it, many of these pieces were confrontational and demanding, drawing attention to some of the same complicated socio-political issues that the protestors outside declaimed.

They also sell for quite a lot of money, the dark fact to which the Occupy-ers object. It’s worth noting that they didn’t protest last week’s Association of Writers and Writing Programs conference, which took place in Chicago; AWP distinctly lacks the glitz of the Armory Show. But the events are more analogous than they look, because essentially, art fairs are conferences. Big, gaudy conferences that happen to have thought-provoking and sometimes beautiful items on display, which outsiders like to see. That the creative industries have been starkly, aggressively commodified is neither limited to visual art nor is it a new concept—it’s far from a perfect system.

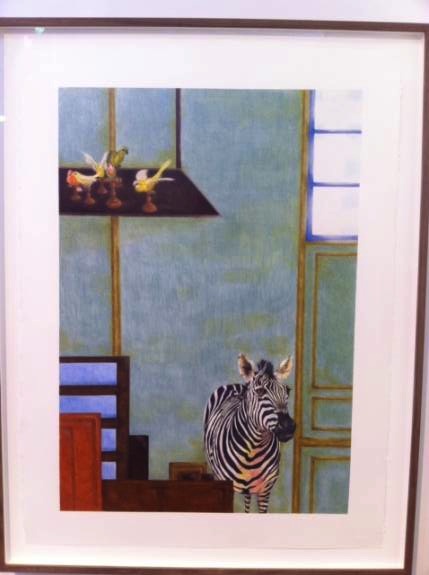

Luckily, you don’t have to be able to buy them to enjoy, say, the haunting Amy Simon colored pencil drawings at the Wetterling Gallery, or the jewelry at the Levy booth that surrealist Meret Oppenheim designed for Schiaparelli in the 1930s. There was a ring whose delicate gold prongs held a sugar cube, a necklace of plastic bones on a silk rope, like Wilma Flinstone chic, and a watch that dangles from a pin, surrounded by silver strips of eyelashes and a pearl tear.

If you did pay the entrance fee to go to the Armory Show, the art demanded that you tune out the cacophonous, contradictory scene of the fair to view it, or that you embraced the spectacle itself. (The thoughtful Ben Davis and Kyle Chayka at ArtInfo compiled a detailed Best Of slide show to use as preparation.) But thankfully, that tunnel vision, that sense of wonder, is what great art does.