On a Thursday afternoon in June 2007, I rode my motorcycle – a poorly built Iranian version of a Honda 125 cc – through downtown Tehran feeling like a time traveler who had entered the city from the wrong portal. The city had turned into a ghost of itself and there was something both splendid and strange in that. Traffic had disappeared; one could actually breathe relatively easily for a change. Gone was that polluted air which usually blankets the city like another official edict no one knows what to do with.

I thought to myself: This is how it must have been forty years ago. For a spell, Tehran actually seemed habitable again, as if some divine hand had reached down and instantly swept away the muck of poison and people. But after a while what had been a uniquely pleasant afternoon ride began to feel wrong, and a sense of foreboding took over. Instead of imagining the quiet, traffic-less Tehran of old, now I thought: This is how it could turn out when the Americans finally decide to attack, or when a mammoth earthquake punches the fault-line on which Tehran was built. It was not impossible to imagine that a mass exodus had taken place. But that could not be. For an exodus to happen, you need gas.

Some days earlier, the authorities had put the whole country on gas rations, accounting for the lack of traffic and people. In the meantime, everyone was jockeying to get what they could from the pumps. I’d first noticed this upon coming back to the city from the Caspian shore. A mile-long line of cars was formed in front of a gas station in the Yusefabad district. In front of the station, soldiers in dark green uniforms were posted with guns. Police cars hung back every hundred yards or so from the gas line watching the slow crawl.

Instead of imagining the quiet, traffic-less Tehran of old, now I thought: This is how it could turn out when the Americans finally decide to attack, or when a mammoth earthquake punches the fault-line on which Tehran was built.

It turned out that around midnight, someone in some ministry or other had finally announced that the dreaded gasoline rationing they’d been talking about for months was finally being put into effect. Immediately, fights had broken out around the country. Panic brought people carrying plastic containers in order to pump a few extra liters as back-up. Chaos engendered further chaos. Several gas stations were burned down – estimates ran anywhere between two to sixteen in Tehran alone. And with the onset of the summer heat, several buildings where people had begun hoarding gasoline had already blown up.

In the provinces the stories sounded wilder still. A friend that I’d been staying with up north called to say that just that morning, a local tough had driven into a gas station heading a caravan of ten cars. Flicking on a cigarette lighter, he’d demanded gas for his entire entourage or the place would go up in flames. The ten cars got all the gas they wanted, for free. In the south-west of the country, it was said that the local minority Arab population simply pulled out guns when asked to produce their gasoline ration cards. And in the north-west, the minority Turks had made mounds of their ration cards in front of gas stations and burned them. People retold these stories around Tehran with grudging respect for Turks and Arabs, the assumption being that, as usual, those folk had shown some real khaaye, or “balls,” while the majority Persian population had characteristically caved in, again, without so much as a whimper.

But the truth is that nobody knew what was really going on. The ration cards had been issued to each owner of a vehicle several months ago and pumps all over the country had had slots installed in them so that you would have to slide your ration card in there (much like you would do with a credit card) before pumping. What no one could accept, however, was that the actual rationing would take place any time soon, if ever. When it actually happened, three liters a day for a car and one liter a day for a motorcycle just seemed absurd. A little metric conversion might tell the story better: there are about 3.785 liters to each gallon. What the government was suggesting was that the average car owner could get by with not quite one gallon of gas a day. Nothing was said of the atrocious state of public transport which made driving one’s car to work a necessity for a lot of people. Then there was the question of how taxicabs would get along from now on, or the tens of thousands of private drivers in towns all over Iran who made their living ferrying people back and forth everyday. Add to that the question of fuel for farmers and their tractors, fishermen and their boats, and one begins to get an idea of the monster that the authorities, in their usual, inimitable way, had created. How would anyone travel anywhere now that everyone was reduced to watching the gas gauge every minute? What if you ran out? Would anyone help you? How could they help you when they were on rations themselves?

Conspiracy theories began to circulate. This was another effect of the American sanctions on Iran, to which there was some truth. The fact is that this country, known for possessing one of the biggest reserves of oil in the world and the second largest reserve of natural gas by far, cannot provide enough refined gasoline for its own population. It has to spend five billion dollars a year on imports.

Conspiracy theories began to circulate. This was another effect of the American sanctions on Iran, to which there was some truth. The fact is that this country, known for possessing one of the biggest reserves of oil in the world and the second largest reserve of natural gas by far, cannot provide enough refined gasoline for its own population.

There is simply not enough refining capacity in Iran, while the insistence on forging ahead with the nuclear program that the Americans are so worried about continues. The combination of fearing a couple of timely precision bombs from the Americans, the extravagant gas usage of the average Iranian, and the subsidized gasoline that had kept gasoline prices preposterously low at 34 cents per gallon, had put the government in a no-win situation. Something had to be done. But if prices were raised to at least compete with Persian Gulf area standards, inflation would hit another overdrive. What to do? Let’s limit gas usage. A fairly logical idea that, as always, was carried out with little planning and zero attention to detail.

To begin with, in a classic case of the left hand not knowing what the right hand was up to, most heads of government agencies, including the police force, had no idea that the rationing was being implemented until they heard it on radio. This is a peculiarity of the Islamic Republic; rather than being a monolithic state, it’s more of a schizophrenic one. The centers of power are many and often feuding with each other. You can think of an alternate, Iranian version of Henry Kissinger’s adage about Europe: “If I want to call Europe, what number do I call?” If I want to talk to a decision maker in Tehran, who the hell do I dial? Do I dial the President, the Supreme Leader, The Council of Experts, the Expediency Council, the head of the Revolutionary Guards, the Ministry of Intelligence, the Parliament…?

Definitely not the parliament in this case, as it was going on its three-week summer leave the day after the rationing proclamation.

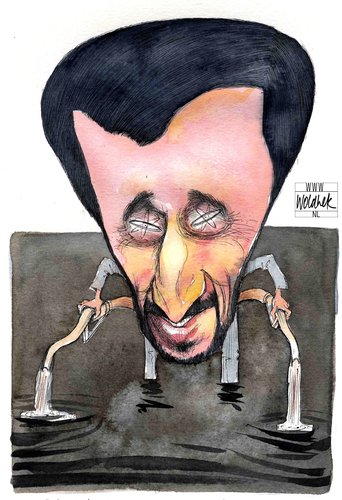

In the end, it was the Iranian President, Mr. Ahmadinejad, who appeared most on point regarding this affair. On TV he displayed his own time-tested brand of fatuous bravado that gives many heads of state sleepless nights these days. He told reporters that the ration cards were the beginning and the end of discussion about gasoline for the foreseeable future. In other words, contrary to all the rumors, no one was going to be able to buy gas at the much more expensive free-market rate once their ration cards were used up for the season. It didn’t matter if you were willing to pay thirty cents a gallon or three dollars a gallon – once your ration card was on zero, you’d have to put your car in the garage for the next four-month rotation.

Now, this did not sit well with seventy million Iranians. Of all the jokes that made the rounds when gasoline rationing began, two seemed to be repeated ad infinitum on the streets and in taxicabs, on text messages and in emails: 1. Somebody asks President Ahmadinejad how is one supposed to get anything done now that there’s no gas. Ahmadinejad’s answers: ‘It’s easy. Just go ride on one of those 17 million asses that voted for me in the last election.’ 2. ‘Dear President, you keep saying that the Shi’ite messiah is on his way. But how’s he supposed to get here on only 3 liters a day?’

But these jokes belie a deep sense of anxiety that has gripped Iran for some time now. On that post-ration-announcement day when I was on my bike in the empty streets of downtown, I gave a ride to a young animation artist who was heading home from Revolution Square.

Just that morning, a local tough had driven into a gas station heading a caravan of ten cars. Flicking on a cigarette lighter, he’d demanded gas for his entire entourage or the place would go up in flames. The ten cars got all the gas they wanted, for free.

He expressed the feelings I’d been having in a nutshell: “We’re all waiting for something to happen. We just don’t know what, or when.” As we rode on, I tried to question him a bit. Was it war that people were expecting? The arrival of the Americans? Another revolution? Or something as uncomplicated as cheap and unlimited gas again? No, he said. It wasn’t one thing or another; it was just waiting for the sake of waiting itself. In the same way, perhaps, that in the days that followed, drivers rushed to the gas stations and waited and waited for hours on end just to fill up their tanks. The absurdity of this behavior gave birth to another round of jokes and hand-wringing a week later, once the hysteria had calmed a little. Did these men and women truly not realize that hurrying to get gas on their ration cards only hastened the inevitable, the moment when their cards would show a big fat zero on them?

But I could only worry so much about other people’s peculiar behavior. I had my own troubles. My motorcycle had been sitting in our basement gathering dust for the past ten months, while I had been out of the country. The first thing I had to do was get it in shape. Which I did. But, once that task had been accomplished, I had to get a motorcycle gasoline ration card – I’d been away when they were first issued. I went to the Yusefabad police station and quickly realized that getting a card was no easy matter. After the rationing announcement, every slacker in town who hadn’t gotten their card yet was after the same thing. So for a couple of weeks I resorted to begging for gas, a liter here and there, from friends. By then the underworld had adjusted to the new situation and I heard stories of how you could buy stolen cards down in the Molavi district, or buy bulk from peddlers coming from the Gulf, or just pay quintuple the rate to the newly important gas station attendants who pocketed the forgotten ration cards of hapless drivers.

Was it war that people were expecting? The arrival of the Americans? Another revolution? Or something as uncomplicated as cheap and unlimited gas again?

I decided it was best to take another trip to the Caspian shore, this time to the home of an old childhood friend in the police force there. I took a ride from Freedom Square with four other passengers, plus the driver. There was only one topic of conversation the entire five-hour ride: gasoline. The young army recruit on medical leave complained that his family, who were farmers, had already had to stock up on three-hundred thousand tuman, roughly $300, of blackmarket gas just to keep their machinery running. Another fellow was convinced that the government had stolen his card and given it to someone else, because no matter which police station he went to they told him he’d already received his card and couldn’t get another. Our driver, too, was on a roll and would not stop cursing the government. They were feeding people second-rate gas, he said. If the rationing didn’t force him to put his car and his livelihood to sleep, then the bad gas would surely bring him and the car to a dire end. Only one of the passengers stayed silent, and when my time came to say something I played my part by whining about how I hadn’t managed to get my card either.

And then I got my card. My uniformed childhood friend simply helped me get it up north instead of having to scramble for it at the Yusefabad police station in Tehran. Once I had the card in my hand, I turned to him and said one word, “Gold!” My friend laughed. I owed him one. He left me at the Nowshahr air terminal where I caught a Tupelov to Tehran, and spent the entire forty-minute flight obsessing over how much fuel the Russian plane was using.

Back in Tehran, the gas panic had subsided. There was bustle and traffic again on the streets. People were, and are, using up their gas ration cards and still waiting, waiting for something – anything – to happen.

All photographs by David Mohammad Yaghoobi

Salar Abdoh‘s latest novel is Opium. He can be reached at zzsalar@aol.com. Click HERE for Part One, “Moving Violations”, in his series on Iran. Click HERE for Part Two, “Vanishing Point”.