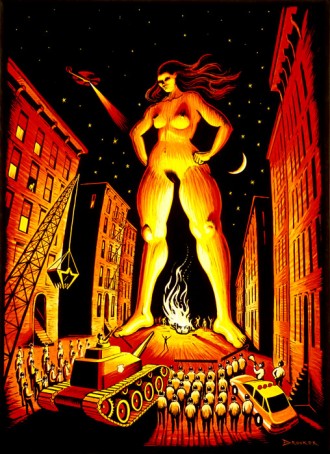

A woman with thighs the size of tree trunks stands on the twilight city street. Below her a tank raises its one truculent eyeball; she stares it down fiercely, hands planted on her hips. This painting, “Colossus Poster” by artist and illustrator Eric Drooker, has become an icon of protest movements around the world. Drooker, whose work includes the Illustrated Howl (created with Allen Ginsberg before the poet’s death) and darkly humorous, sometimes ecstatic New Yorker covers, knows full well the importance of art in political movements. Taking a page from underground Russian samizdat, Drooker has internalized his political beliefs and his art reflects this—making it both intensely moving and yet not at all didactic.

I met Eric Drooker at a slideshow of Howl in San Francisco’s Beat Museum, caddy corner from City Lights bookstore and cheek-by-jowl with the Hungry Club: Topless Entertainment and the dubious Basque Hotel. As I made my way through the museum’s downstairs to climb a rickety back staircase, I thought it appropriate that Drooker was showing his work here at an intersection of literary counter-culture and seamy sub-culture. I arrived late, and as I climbed over the crowd to get to my folding chair in the small, woolly room, the slideshow started, showing images of a writer on a rooftop with stars falling onto his head, clambering over chimneys in the dark and then clambering over phalluses, some quite aggressive.

New York-based artist Molly Crabapple’s work is similarly political yet playful. Crabapple has illustrated numerous book covers, created backdrops for burlesque venues like The Box, and authored a successful graphic novel, Scarlett Takes Manhattan. Both she and Drooker have been active in the Occupy movement, for which they’ve created eye-catching posters that they’ve offered as free downloads online. Like Toulouse-Lautrec, one of the fathers of poster art, they aren’t afraid of using sex in their work to grab your attention: they pull you in by the belt-loops only to school you in the talking points of the revolution.

More than many writers covering Occupy, Drooker and Crabapple have articulated the movement’s core ideals. Both artists are passionate about free expression, and explained how art can have a primary role in aiding protest movements. Working primarily in illustration, their artwork has to serve two masters: it must be instantly graspable and offer something important on closer inspection. While not all illustration does this, the best illustrators are adept at this striptease.

While Crabapple and Drooker didn’t know each other before this interview, some years ago, Crabapple volunteered at a slideshow of Drooker’s work in St. Mark’s Church. They connected by fondly remembering May Day Books, a pop-up bookshop in the lobby of the Lower East Side’s Theater for the New City that as Drooker remembered featured “chicken wire protecting the books, so the books couldn’t escape.” May Day was also where Crabapple once hung out, did homework on the couch to escape her tiny, windowless apartment, and first became familiar with Drooker’s work. She began the interview by explaining the influence Drooker’s work has had on her own artistic evolution and her decision to focus more on political and protest art.

The following conversation took place via Skype. I’d originally planned to moderate the discussion, but Crabapple came more than prepared. Her questions were almost entirely what was on my list, so I sat back and enjoyed a free-flowing conversation between the two artists. Crabapple began by explaining the influence Drooker’s work has had on her own artistic evolution and her decision to focus more on political and protest art.

—Tana Wojczuk for Guernica

Molly Crabapple: When I think of your art, I always associate it so much with this sort of tragically “gone” era of the Lower East Side—when the Lower East Side was poor people and artists, and it was a working class Latino neighborhood. I get this hardcore nostalgia bomb when I see a lot of your stuff.

Eric Drooker: The neighborhood has been in transition for decades, centuries, I guess. When I grew up there, it was certainly a mostly working class neighborhood and I have roots [in the Lower East Side] because my grandmother was born there, on Fifth Street and Avenue C or D. I grew up on Avenue B. The complexion of the neighborhood has changed pretty radically in the last fifteen years. It comes in waves and it depends who you talk to.

Some people think that it’s improved because it’s much safer now, you’re less likely to have some junkie pull a knife on you now, but you’re more likely to get mugged by the landlord every four weeks, for much more money. You get mugged, they take five dollars, twenty dollars—but the landlord wants one thousand or two thousand dollars every four weeks. They’re never satisfied.

I’ve found that the neighborhood has been more dangerous for artists. It’s a more hostile, dangerous neighborhood now than it was then when it was mixed, lower class, bohemian. Artists always live in the cracks anyway, whatever culture they’re in. They’re usually accustomed to not having much money, to kind of roughing it. So we’re not so fazed by it all. But we’re a small minority of the population.

Molly Crabapple: You got your start as a tenants’ rights organizer [in New York] and your art very much came out of your politics. What do you think about the intersections between art and activism?

Eric Drooker: Ah, Molly, what do you say to that?

Molly Crabapple: People are always asking me about it. I’m interested in hearing what someone else says.

Eric Drooker: Well, [laughs] ok, let me see: art and activism. I can always fall back on, “the question should be, what isn’t political? Everything you do is political, even if it’s abstract. You’re making a political statement even if it’s unwittingly.” I think so much of art is unconscious anyway, the artist doesn’t know the real reason they’re doing it. They’re just kind of going along with it intuitively. The unusual thing about doing this street poster art—or something with a conscious social critique in it—is that the artist thinks they’re a little in control, focusing and trying to make a specific point. But even then, when you look at it a few years later, you realize you were just working through some of the usual feelings you were going through during that time.

When I was in my early twenties I was doing tenant organizing—rent strikes, specifically—in my building. I think that was how I started doing poster art. It was something very concrete.

I realized not too many people were showing up at the tenant meetings, I put up a sign in the lobby of the building: “Tenant Meeting, Thursday Night, Apartment 14.” I got the distinct feeling that most tenants felt like, “Why would I want to go into somebody’s apartment? Tenant meeting? Ugh.” It smacked of … a bunch of busy-bodies or something. People didn’t want to go. These were Americans and they didn’t really have any experience with something as basic as “community.”

Art grabs people by their eyeballs, it seduces them … art is a means to an end rather than simply an end in itself. In art school we’re always taught that art is an end in itself — art for art's sake, expressing yourself, and that that’s enough.

But then I discovered that if I drew a picture, a little piece of artwork on the flyer hanging in the lobby announcing a meeting on Thursday night, that more people would show up. The art was just a way of hooking people in, saying: “Hey, maybe there’s something cool about the tenant meeting. If the picture’s really cool and weird, maybe I should check this out.” And I think all of my art has really developed out of that realization.

Art grabs people by their eyeballs, it seduces them. Especially if the picture is very beautiful or very sexy or just really weird, if it has some surreal element in it. It makes people do a double take and then, if they’re looking at the picture, maybe they’ll read the text under it that says, “Come to Union Square, For Anti-War Meeting Friday.” I’ve been operating that way ever since—that art is a means to an end rather than simply an end in itself. In art school we’re always taught that art is an end in itself—art for art’s sake, expressing yourself, and that that’s enough.

Molly Crabapple: Which is so arid, if you think about it. One of the things that always frustrated me—because my roots are as an illustrator and I’ve spent much of the last year doing work around Occupy Wall Street—was the idea that if art was somehow engaged in the outside world in any way, it became no longer art. To me, that detaches art, sterilizes it, locks it up in a white-wall gallery and makes it just a commodity for rich people. I was more moved when I saw people holding my art as protest signs or re-pasting it in squats than I was in any gallery show I’ve ever had, because my art was becoming more a part of every day life.

Eric Drooker: I feel the same way. We both are illustrators trying to make Benjamins to pay off the landlord. Illustrators are usually illustrating something big or commercial if not outright advertising. It’s a form of prostitution, but that’s cool because we don’t have any moral hang-up about it. The problem with prostitution in my experience is that it’s often unsatisfying. It’s unsatisfactory for the client, for the John. The client isn’t quite satisfied and then the prostitute is always unsatisfied but is doing it just to make ends meet. And if you’re doing fine art, if you’re doing it for a gallery or a museum, it’s so sterilized. It’s such an antiseptic environment.

What’s that Regina Spektor song? [Museums] are like mausoleums. Having your work in a museum is something we as artists aspire to, but I don’t think that’s something we need to worry about while we’re alive. Typically your work will end up in a museum [after] you’re dead. And maybe that’s the function of a museum. It’s an archive of your work after you’re dead. But while we’re alive, I like to see it in places where it’s connected to day-to-day life and making a difference. Specifically, what was happening down on Wall Street. So much of it was this creative outburst, which I think is what gave it so much power. And what made it so threatening.

Molly Crabapple: It’s like the tenants’ meeting and how no one wanted to go to that: people in the U.S. didn’t know how to engage in political action because it just seemed so ungodly dreary and hopeless. And then suddenly there was this ecstatic thing that everyone was part of—from old school union guys to crust punks—it was beautiful and freeing. People were playing the cello and singing even though they might get their heads smashed in. It became this amazing outpouring of all the shit that we had suppressed over the past decade.

If I do a picture, I want the audience to be the people I was just packed against on the subway or on the street, walking on Fourteenth Street. I don’t want it to be some narrow public that I myself feel alienated from.

Eric Drooker: I found myself, especially in that first couple of months, in this heightened emotional state, on the verge of tears much of the time—watching it, getting involved, hearing what young people were saying on the street corner. Contrast that with what we’ve been taught is the proper role of art, which is that you want to have it very neatly matted and framed and put on a white wall in some room where only a certain class of people are going to go in.

Sometime when I was in my mid-twenties I noticed, “Hey, even I don’t go into too many art galleries. Why? Because I don’t like the vibe in them. If even I’m not going into galleries, then who goes into art galleries in the first place?” It’s just a certain, very narrow percentage of the population. Don’t you feel like you want to be talking to the masses of people with your artwork? Especially if you’re in New York and talking to a mix of people every time you’re on the subway. If I do a picture, I want the audience to be the people I was just packed against on the subway or on the street, walking on Fourteenth Street. I don’t want it to be some narrow public that I myself feel alienated from.

And maybe that’s one of the falsehoods behind doing the kind of art we do, where we are attempting to speak to the broad public. If you make a street poster and literally paste it on the street in a city like New York, where it’s such a mixed population and so densely populated, and it stays up for a full week and doesn’t get covered up by something else or pulled down, you will have fifty thousand people who will have seen it. It will be the poorest of the poor—some homeless man who lives on the street will see it and probably appreciate it, or some businessman or landlord will see it. Everyone will see it. And whether or not they even realize that they saw it, on some level it’s affecting their consciousness.

That’s about as religious as I get–that’s my faith, that even if people screen it out and didn’t think they saw it, they did. Even if it was for a split second, it’s become part of them and it’s affecting them somehow.

Molly Crabapple: One of my favorite pieces is your illustrated “Howl.” What I loved about that so much is that “Howl” is such a mad, ecstatic, visceral poem and I felt that your illustrations got that. That is something very hard to translate into still images, but you did. This is probably the most clichéd question ever, so I apologize in advance, but tell me about the process of working on “Howl.”

I illuminated [Allen Ginsberg’s poems] with paintings and drawings that bounced off of them. You want the picture to relate to the text without it slavishly regurgitating it or merely illustrating it, because that’s redundant. You want to show another angle of what the text is saying.

Eric Drooker: When Allen was still alive, he was very much what we’re talking about; he was an artist, but he was very local. He was just another wing-nut in the neighborhood and he was very accessible. [You’d see him] in Tompkins Square Park or in the local delicatessen, in one of the greasy spoon restaurants on First Avenue or a Chinese restaurant. The last time I saw him, he invited me out to dinner at this little Chinese restaurant, a hole-in-the-wall on First Avenue and Twelfth Street or Thirteenth Street near where he lived. We had collaborated on one of his last projects just before he died in the spring of ’97, a book called Illuminated Poems—it was Allen’s poems and songs and I illustrated them. Or, I illuminated them with paintings and drawings that bounced off of them. You want the picture to relate to the text without it slavishly regurgitating it or merely illustrating it, because that’s redundant. You want to show another angle of what the text is saying.

We did several dozen of these collaborations—pictures to go with Allen’s words. The book came out and it became an underground classic. At a certain point, I got a call from movie directors based in San Francisco who were going to be making a movie of “Howl” because the fiftieth anniversary of the poem was coming up. At first, they thought they were going to simply ask for permission to use my images to go along with their documentary about the poem, but then when they came over to my studio here in Berkeley and they saw some of the sequential art and I showed them a couple of my graphic novels, they realized that the pictures themselves could really be telling the story. And since there wasn’t much footage of Ginsberg back in the ‘50s, they didn’t have that much archival material to work from. They didn’t have documents to make their documentary from.

That’s where they came up with the idea to hire me to animate the goddamn poem, to actually animate the goddamn poem, which I thought was way too ambitious. First of all, it’s a very long-winded poem. It goes on for almost half an hour when Allen reads it out loud. And it’s so abstract, how do you try to illustrate something like that? Much less animate the motherfucking thing? And there’s the fact that animation is extremely time-consuming, tedious, labor-intensive, and therefore, extremely expensive as an art form to really do it right, to really do full animation. But they told me that they would hire a full animation studio to work with me and they would be bringing my pictures to life, so how could I say no to that opportunity?

But it proved to be a very different way of working than I’m used to because I hadn’t really ever done animation before.

Most visual artists, just like most writers, tend to be solitary. While they’re doing the art, that is. They may have a crazy orgy that morning, but at a certain point they kick everybody out, and say: “Come, go home. Yeah, I had a great time too.” And then you’re alone again, and then you’re freshly inspired and energized.

Eric Drooker: I’m accustomed to just working by myself, alone in the room and cranking up the music and just working and getting all into an obsessive state where I’m focused on this thing, and it’s the one thing that I feel like I may have a little bit of control over in my life.

Howl the movie was very much a collaboration. The book, the graphic novel, that came out afterwards was kind of a byproduct of the movie; I had way more control over that. Once again, it was just me alone in the room and I was able to pick and choose what I thought were the most powerful, successful frames from the whole movie to illustrate the poem.

We all know artists who like to collaborate, who like to work as a team. It all kind of depends what your habitual working method is. Most visual artists, just like most writers, tend to be solitary. While they’re doing the art, that is. They may have a crazy orgy that morning, but at a certain point they kick everybody out, and say: “Come, go home. Yeah, I had a great time too.” And then you’re alone again, and then you’re freshly inspired and energized. Even if I have one other person in the room, just quietly reading in the corner, that’s too much. I get distracted. I have to kick them out.

Molly Crabapple: I have a weird thing with solitude and community and working. I am intensely collaborative with my work, but I like to do all my pieces in a dark corner and then give them to other people. I sometimes feel like what got me into art was that I was this weird, twitchy little kid who couldn’t talk to anyone and drawing people was the only way I could get people to like me. I feel like I’ve spent much of my life using my sketchpad to take that certain [person] who interested me and kind of seduce them or win them over or get to understand them through drawing them. But then, of course, once I steal their essence I go to my dark little burrow again and make pictures of them.

I had been drawing her in a series of drawings, and then she was conjured up by the drawings and then there she was! This beautiful Italian woman with long hair, and it turns out she grew up in East New York, way out in Brooklyn. She moved in and she was living with me for a while. She was the muse for that poster of the giant woman standing in the middle of the street, with the police surrounding her.

Eric Drooker: I try to, at least once or twice a week, have someone over and model, usually a dancer friend or a poet or someone to come over and just stay still for me. Depending on how exhibitionist they are, it will determine the finished work. And I say, “You’re the muse; you come up with it. I’ll draw you however you want.” And I feel like that’s more of a collaboration and a way of communicating with them through art. It’s almost a very different type of art—maybe even a different part of the brain that I’m using—than I use when I’m doing my very finished work or street poster art.

Molly Crabapple: Speaking of muses, you have this very iconic woman that you frequently draw. She is in this white dress and she has black hair. She’s the subject of Blood Song [a graphic novel]. Tell me about that character.

Eric Drooker: As you know, artwork has this magic. I don’t even believe in magic, or ghosts or anything like that, and yet in a city like New York, on the subway, I definitely see ghosts and art seems to have some magical properties. If you draw something or paint something, it often appears. That’s what was the case with that woman. I had been drawing her in a series of drawings, and then she was conjured up by the drawings and then there she was—this beautiful Italian woman with long hair, and it turns out she grew up in East New York, way out in Brooklyn. She moved in and she was living with me for a while. She was the muse for that poster of the giant woman standing in the middle of the street, with the police surrounding her. Do you know that one?

Molly Crabapple: I do.

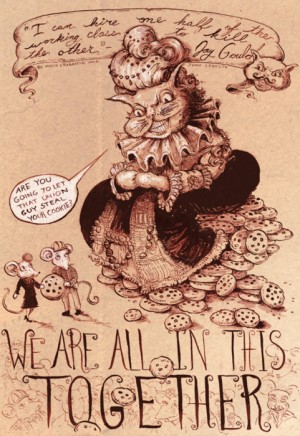

We used to call the 1% the ruling class, but America’s never felt comfortable using that terminology. It was taboo to talk about class war. Americans are okay talking about it like this; everyone wants to be part of the 99%, even the cops are like, “No, no, man. I’m part of the 99% too.”

Eric Drooker: It was when Giuliani got elected the first time around, and to show that he meant business he showed up on Thirteenth Street and Avenue B to evict the squatters. He showed up with a tank, a Korean War-era tank. They called it an armored personnel carrier, but it sure looked like a tank. It had the caterpillar treads, just like in the movies. There it shows up on Avenue B, and I was so outraged and just freaked out, which I guess was the intention, so I got to work immediately on a poster, because poster art was always my way of being involved in the conversation. So it wasn’t just a one-way conversation with the police yelling at us or freaking us out. Street posters allowed you to have the last word. If you put them up in your neighborhood, you were speaking to your neighbor. So I did an image of all the protesters and the police on Thirteenth Street and Avenue B with all the tanks, except the scale was all different.

The woman was fifteen, twenty stories tall. The model for the poster was this girlfriend, this lover, who was living with me at the time. Except she was this very skinny Italian woman, but in artwork you can do whatever you want, so in the finished drawing I fleshed her out. I gave her these really big legs so that she looked like she was really planted firmly in the street, that she had a connection with the earth. She wasn’t going anywhere. That’s ultimately what that whole squatter struggle was about, it was about territory and the land and who controls the turf. Any time the real estate interest complained, the police would show up and kick people out of Tompkins Square Park, try a curfew, or try to evict people from the local squats in the neighborhood. It seemed to always be fueled by real estate and it was this ongoing war–it’s still going on, of course – between people and this minority, it’s called the 1% now?

Molly Crabapple: Yeah, the 1%.

Eric Drooker: We used to call the 1% the ruling class, but America’s never felt comfortable using that terminology. It was taboo to talk about class war. Americans are okay talking about it like this; everyone wants to be part of the 99%, even the cops are like, “No, no, man. I’m part of the 99% too.” No one wants to be part of the 1%.

The poster art over the years, art with social critique in it, has always been on that theme. It’s been trying to make that point–that we are larger than they are. They may have guns and pepper spray and helicopters and F16s and the whole U.S. military on their side, but when it comes down to it, we still have the numbers.

And that’s why I played around with scale. I made the woman huge because it’s showing that we are larger than them and the police are much smaller than that. That’s just a gimmick that I use in my images, playing around with scale, or drawing very realistically, but then having one element blown out of proportion, which often has a comic effect. Humor is a potent thing to use in one’s art. [But] I find it very difficult to be funny, it’s much easier to do tragedy than it is to do comedy.

Molly Crabapple: Why do you think that is?

Eric Drooker: There’s so much tragedy in people that we see every day that we don’t have to make anything up. We don’t have to invent anything. There are two items on the menu: comedy and tragedy. We all know what tragedy is. “Yes, I’d rather not have any more tragedy, please. I’ll have comedy, please.” Comedy, in the Greek sense, only means that it has a happy ending.

It doesn’t mean humorous, “ha-ha.” Like Dante’s Divine Comedy: you have Inferno, which is the famous one, and then Purgatory, but then it ends with Paradiso, “Heaven.” So he called it a comedy because it starts out in Hell and you can only reach Heaven by going down through the Nine Circles of Hell. It has a happy ending. Doing art that has a happy ending, that doesn’t seem really corny, is extremely difficult to pull off convincingly.

Molly Crabapple: For most of my career, I only did work that was funny or satirical or sexy. And it wasn’t that I wasn’t interested in doing critical work, or I wasn’t interested in doing tragic work, it was that I felt like I didn’t have the right to. There were certain chops I thought you had to have to do that, and I just didn’t have them.

Eric Drooker: Gravitas.

Molly Crabapple: Exactly. Gravitas. And I thought I had to stick to a certain type of work. Occupy Wall Street made me say, “Fuck that shit.” I had been unwilling to put myself on the line and deal with tragic things, or deal with political things, or deal with grave things in life. I was kind of copping out and hiding. It really liberated me once I was able to — and once I gave myself permission—to deal with that sort of work. It’s interesting what sort of things come easily and come with difficulty to people.

Eric Drooker: When I was younger, when I was a teenager, the work was more satirical and funny and cartoony. And part of it was chops–if you have a more limited repertoire of stick figures and cartoon characters, they lend themselves more to humor than to tragedy. But certainly by the time I was in my early-twenties and was living there on the Lower East Side, I was so surrounded by tragedy that I think that inspired me to try to reflect it in the artwork.

As I developed as an artist and studied art history, I noticed that all the great works were dealing with the human condition. [Art] had humor in it. It had sex in it. But it also had sorrow running through it.

[Art] is one of the few ways we have of dealing with things that frighten or anger us. Art is one of the few places where you can put it in a constructive way where it won’t burn you up inside or hurt anyone. Often, we don’t even realize we have these emotions until after we have completed a whole series of paintings. We look at them a few years later and we realize, “oh, I guess I was really emotionally shut down during this period.” But at the time, we don’t realize that. It’s like art history, we look back and can start to see patterns emerging.

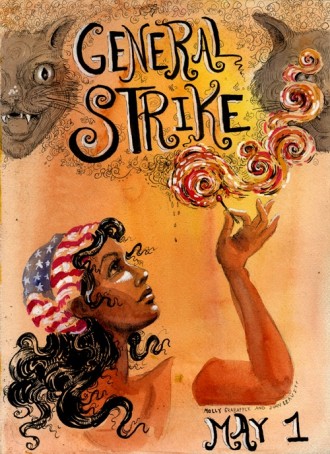

But, Molly, the first thing of yours that I saw that I was aware that it was you doing it, was a couple of months ago with your May Day General Strike Poster. I like how it was not only announcing this hardcore direct action, the general strike, but in the image you have a lot of optimism and a lot of beauty. It’s difficult to get that, to convincingly communicate those things in the same piece.

Molly Crabapple: Thank you. I was inspired by the 1888 Matchgirl Strike in London—one of the strikes of the Labor movement. These girls who made matchsticks were dying of phosphorus poisoning because there weren’t adequate facilities, and they were just being worked to death and they would get this condition called phossy jaw, where their jaws would necrotize.

Eric Drooker: It’s sounds like William Blake’s “dark satanic mills.” Of course, Blake was writing at the very beginning of the Industrial Revolution. It was the 1780s, but he was so prophetic.

Molly Crabapple: Me and Natasha Lennard, who is an organizer at Occupy, were talking about how very often these labor posters, they have one image of how a worker looks like, which is this big, strong, burly industrial worker who’s a man. And I love that image. I think it’s a great image, but we were talking about how it wasn’t reflective of so many of the people who do the shit work in our society. So I wanted to do a Latina woman instead.

Eric Drooker: Even though it’s not clear, it could be an Arab woman. You don’t know what her ethnicity is. All you know is that she is not Scandinavian.

Molly Crabapple: Exactly.

Eric Drooker: It’s not Paul Bunyan. It’s what more and more of the workforce looks like. People don’t work in factories, [they aren’t] big muscular guys. The working class is flabby because they’re sitting in front of a computer all day, but it’s still their labor being extracted. Working people are working even longer hours, even though we won the eight-hour workday at the Haymarket General Strike in Chicago.

In the U.S., ironically, people work longer hours in the U.S. than they do in Europe or in any other industrialized country. They seem utterly oblivious to May Day, don’t really know what it is—our own history. They don’t realize that May Day is this radical workers’ day, celebrated all over the world. Not just in Cuba and China, but in France, England, Canada. Everybody has the day off on May Day and they are commemorating this moment in history that happened right here in the U.S., in Chicago.

Molly Crabapple: It’s this strange thing, America. Our class system is not explicit, and people think that they will somehow magically become millionaires and don’t fight for their actual rights.

Eric Drooker: And that’s why there hasn’t been an outcry to tax the rich over the years. The only rational explanation is that we’ve fallen for that Horatio Alger story.

I think for an artist there are so many things to make pictures of now, that everyone else may be suffering, but at least artists will just be stimulated by it all. If you look at the paintings of Peter Brugel or Rembrandt or Francisco Goya’s engravings, all the really good shit. Or Picasso’s “Guernica.” All the really amazing stuff through history was about some kind of social crisis that the artist lived through, like we are living through now.