There was a black-and-white movie of a very small baby

that would not move and she looked just like a baby would

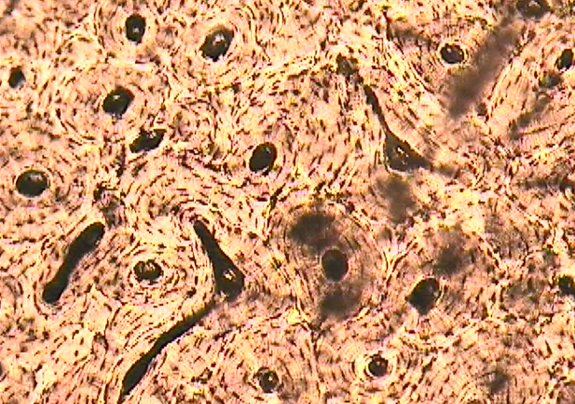

if you tucked her under a microscope. A nurse tried to explain

what to expect next. Words like blood clot and how they’re hard

to describe if you’ve never had one. I’d been reading 17th c.

rituals of the Bacabs, who were the Mayan medicine men,

whose incantations have many lines about blood as a needle,

and I’d been reading the 17th c. case study of an English woman,

also named Kate, bleeding and sweating forth needles, page

upon page of it, until I wished, for her sake, she would die.

On the 7th day she took 80 drops of tinct. theb. without

the least effect, complained of frequent rigors succeeded by heat.

On the 8th day she could get but little rest from a universal

soreness of the right side, which she described as if her ribs

were falling out of her sockets. I was bleeding a lot then,

but trying to pretend it was OK, because they say you’ll bleed

a lot and a lot is subjective and so is how long. And if

I’ve learned anything, it’s every time you go to a doctor

they put something metal in your vagina and sometimes it’s sharp

and sometimes it’s not and sometimes your baby lives

and sometimes she does not and sometimes you stop bleeding

and sometimes you start. The doctors always have a reason

and you are always expected to believe in reason. I’d read

the first Bacabs were four brothers who stood at the corners

of the earth to keep the sky from falling.

The madness coil was made at the place of the Lady-

needle-remover-of-clotted-blood. Cast it away.

And the snake fell. Four days prostrate in that place.

Then he bit the arm of the madness of creation.

He bit the arm of the madness of darkness.

He licked the blood from a leaf. He licked

the blood from the stump. Cast it away

into the earth, into the underworld, the brimstone,

the fire, the belly of its mother, she-who-keeps-closed-

the-opening-of-the-world. Into this opening, cast in

the labored breathing. Cast in the soured atole.

Cast in the virgin cacao and the virgin seeds.

Cast in the herbs and venom. Then how with a needle,

pry out the heart. There came forth then, oh how?

Frightened, oh how, is your vigor, when it falls.

Your breath, when it is taken away. Frightened,

oh how. Of creation, oh how. Of birth, oh how.

Stopped before me and behind. It stops, oh, it stops,

it is broken. Broken open is the beak, then. Broken,

then, is the groaning. Broken, then, it ends.

I have a full copybook of notes on Kate Abbott’s bleeding.

Crying in the library, I couldn’t stop turning the pages

of the doctor’s handwriting. First he suspected she swallowed

the pins herself from compulsion, but then no, that was not it.

He couldn’t say. I had the idea we had the same illness

though certainly we did not. I sweat, then bled through

the sheets. Something sharp was being drawn out of me.

On the 20th day she had nothing come away from the sore

but a few pieces of bone; she coughed and expectorated

a dark foetid matter, complained of a great pain in her stomach

as if a large needle of bone was there. By the 67th day she was

reduced to eating only milk and rice, which oozed then

out of her sores. If it were me—. The doctor gave 120 drops

tinct. theb. He couldn’t say.

The disease of the Rattlesnake—he enters into

the needle, tongue of the spindle, tail of the thimble.

This is his heart, a red bead. He enters to the crest

of the verdure. Then how, cooled the red firefly.

Then how, cooled the white firefly.

Eleven years passed unnoted, then this: Saw K. Abbott today

in the marketplace. Inexplicably well, mother to two. Shall I tell you now

about my beautiful child? Shall I tell how she’s going to live forever?

Kathryn Nuernberger is the author of Rag & Bone (Elixir, 2011). New poems can be found in West Branch, Cincinnati Review, 32 Poems, and on Versedaily.com. She teaches at the University of Central Missouri, where she also serves as poetry editor for Pleiades.