O

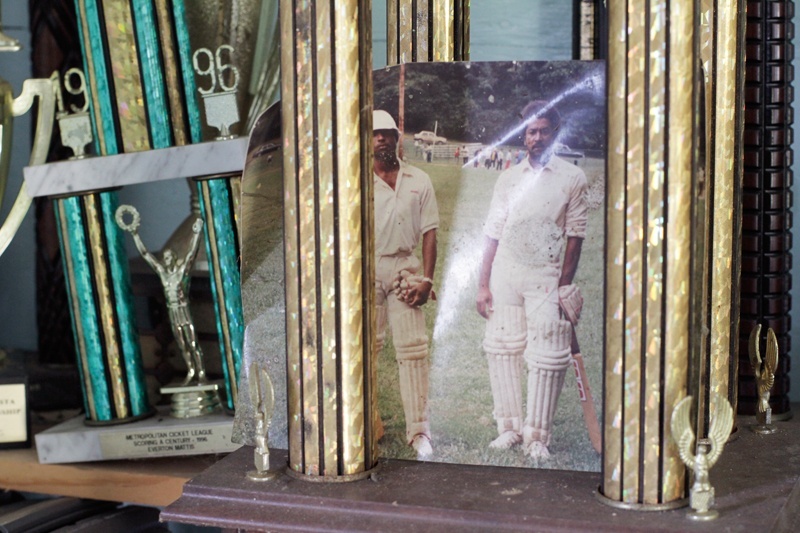

n summer Sundays a group of men descend onto the green fields of Jamaica Bay’s Gateway Park in Brooklyn. Dressed in white from head to toe—trousers, sleeved shirts, and wide-brimmed hats—the scene almost resembles a religious ritual. But the men have gathered to play cricket, a bat and ball game that first originated in sixteenth-century England, and was later transmitted to the West Indies, Australia, and India through the country’s imperial pursuits—and that’s been continuously practiced about the globe ever since, taking on increased significance in the forging of post-colonial nationhood and identity. In the newly released A Gentleman’s War—a transmedia documentary that includes interviews with scholars of the sport, photographs of fans and players, as well as documentary shorts—filmmaker Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich follows one contemporary cricket team for a single season, staging a compelling story of black diaspora, belonging, and beauty.

—Ashley James for Guernica

Guernica: How did your interest in this project arise?

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: My work as a documentarian has looked to the stories of the African diaspora and the urban. I’m interested in finding lived cultural aspects within urban environments that are underrepresented and turning them into images that complicate conversations of identity.

It was while in the midst of working on a series of photographs inspired by Edouard Glissant’s Poetics of Relation that I first became aware of how competitive the sport of cricket was in New York. I was in Cambria Heights in Queens walking down to Linden Boulevard and came across a cricket match. I ended up spending a really special afternoon there observing the game. Over a year later I proposed A Gentleman’s War to the National Black Programming Consortium and they provided funding.

Guernica: Your work evokes C.L.R. James’s quasi-memoir Beyond a Boundary (1963), which uses cricket as a conduit for meditations on race, empire, and aesthetics in the colonial West Indies. Do you see shifts between the context in which he wrote and that of urban—and increasingly gentrified—Brooklyn?

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: I was reading C.L.R. James’s Beyond a Boundary while shooting. His writing was really a road map for me. There’s a reason James writes his memoir through the lens of cricket: the implication is that this is how he wants you to know him. Many of the cricketers I met shooting A Gentleman’s War, especially of an older generation, have a similar relationship with cricket—that the sport is intertwined with a sense of self.

The institution of cricket is in many ways closer to the black church than American athletic mainstays such as football or basketball. Many cricketers, especially throughout the diaspora, feel most connected, most celebrated and respected, at the Sunday cricket match. The culture of the match is also a platform for reinforcing and cultivating family. Although the leagues in the five boroughs are primarily male, every member of the family attends matches from the eldest to the youngest and they are all day events that include full dinner and music.

The New York leagues are very much tied to the maintenance of the West Indian and Pakistani immigrant communities of the outer boroughs. Cricket has been able to flourish in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island on the fringe of growing gentrification. Many of the parks the sport is played in are difficult to get to from Manhattan, buried in some of the vast and beautiful parks that serve communities such as Canarsie, East Flatbush, and East New York, as well as Pelham Bay in the Bronx. I do wonder how that will change as gentrification pushes farther out into the boroughs.

The archetype of the cricketer is a British and, one might argue, dated version of masculinity.

Guernica: How much does the history of English imperialism inform your project? Is it a history that you felt on the field?

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: It is unquestionably a history one needs a sense of to comprehend the significance of cricket in the Caribbean and its diaspora today. The archetype of the cricketer is a British and, one might argue, dated version of masculinity. The narrative of cricket, established by James and by films like Fire in Babylon (2010), situates the cricket field as a symbolic stage for the fight for equality by people of African descent in the British colonies.

During the golden age of the West Indies team, starting with the Frank Worrell era of the 1950s up through Viv Richards’s prolific exploits in the 1970s, cricket was very much a space where the desire of Caribbean nations to be recognized as sovereign and formidable on the world stage came to fruition. There are parallels between the failure of the short-lived federation of former British West Indian colonies in the early ’60s and the success of a unified West Indies cricket team in international test matches. It was only on the cricket field that this political ideal for a unified Caribbean was able to manifest.

However, my overall purpose with A Gentleman’s War was to highlight what I saw as culturally valuable within a black American context—the ways the identity of the cricketer has manifested in post-colonial, contemporary, urban contexts. The farther away the culture of the sport gets from England, as far as, say, Canarsie Park in Brooklyn, the more provocative it becomes. In light of national programs like My Brother’s Keeper (Barack Obama’s initiative to improve opportunities for men of color), and the concerns we have as a community and as a country for the perception and institutional disenfranchisement of black men, I want to place the cricketer in the American landscape of today. There is a lot more out there in America in terms of fraternities of black men than, say, hip hop, and I wanted to shine a light on one of those communities.

Guernica: Do you find that the current twenty-first-century iteration of cricket still holds radical potential?

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: This is a really incredible question. Elder generations of cricketers worry about the survival of the sport in the Caribbean and the future tenability of the sport in the states. Even in many former British colonies in the Caribbean, cricket’s popularity is threatened by track and field and soccer among the younger generation. The true growing market for cricket is actually found in South Asia in India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, where cricket fanaticism remains mainstream.

The radical potential for me as a documentarian didn’t lie in the sport’s continued marketability in places like the United States, but rather in the ways that intergenerational exchange and inclusion is built into the sport of cricket and its club model. Because cricket is a game you can play well into your forties, teams are often composed of players ranging between teen and middle age. Clubs that finance and support a team both in the U.S. and on the national cricket circuits in the Caribbean as well as the U.K., are often grassroots community organizations, kept alive by an elder generation of former cricketers and their families.

Within the construct of the club, a teenage player always has a number of elders with whom they are in conversation. Jeff James, the manager of Progressive Cricket Club, said to me during production that you need both the strength of the young and the wisdom of the old to win a match. This is culturally radical when one compares it with a culture of athletics we have here in the states that puts performance and physical aptitude over community and the cultivation of one’s character.

Guernica: The film closes with Progressive’s defeat at the white clothes finals. While there is a palpable disappointment following this loss, A Gentleman’s War presents cricket not only as sport, but as community. How much did competition color the atmosphere?

The outcome of a league game is not a small thing but represents for many of these men the sweetness of life.

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: Many players have had or hope to have professional careers either on the new national USA team or playing within the Caribbean on a national team. Some players even make it from New York’s Metropolitan league onto the West Indies team, which plays international test matches. So as you can imagine the pressure to win and perform within the league is intense. Although it is a Sunday league, rosters for the top teams are stacked with the best available players from the Caribbean as well as the tri-state area, and fandom really reaches a fever pitch the closer the season gets to the finals.

I wanted the longer film piece to capture this fervor. I wanted you to get that it was a big deal to these men what happened on Sundays, and that the outcome of a league game is not a small thing but represents for many of these men the sweetness of life.

Guernica: What does it mean for cricket to be a “gentleman’s game”? How does it offer an alternative performative masculinity, particularly for black men and West Indian immigrants?

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: When Viv Richards led the West Indies team to victory in the 1970s, the players from the Caribbean were taunted by a racist British media as degrading the expectation of conduct of the gentleman’s game. This critique was re-appropriated with pride: many a Caribbean cricketer will tell you about the aggressive and proud black cricketer, embodied by a Viv Richards or a Michael Holding. In other words, in the beginning, “gentleman” was really a code for white, or British as opposed to African, and that was something Caribbean cricketers played to strike down through fighting to be recognized by exclusive clubs and in international competition.

For me the West Indian cricketing culture is specific: not just an offshoot of a British sport, but an entity in its own right. If cricket is the gentleman’s pastime in England, it is fierce and dignified as a gentleman’s war in the Caribbean!

Guernica: I was struck by Mark McMorris’s childhood memories of the lengthy preparations required for cricket games, including the washing and ironing of the requisite brilliant white uniforms. I wanted to know exactly who completes these tasks. Is it women?

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: It is important to acknowledge here that there is professional and amateur women’s cricket, although at a smaller scale, and no organized co-ed play at least in the states at the senior level. Within the traditional cricketing format women were an important part of the club, which Mark recalls growing up with his father, former West Indies player Easton McMorris. Women play a supporting role in men’s club competition, packing lunch for the players and taking interest as fans in the performance of the team. Within the Metropolitan League there are spouses and daughters who come to every match and even take part in strategic club meetings.

Guernica: Did the particular aesthetics of cricket impact your aesthetic choices as filmmaker?

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich: The setting of a New York cricket match is surreal. Many of the parks where these matches take place feel like another part of the country entirely. I wanted to evoke the magic of stepping off the street in East New York in Brooklyn into the thick of a match in one of these parks and to provide a sensory experience more than a narrative one. The whole summer of shooting there was no rain until the end of the finals, which makes for that beautiful footage at the end of the documentary short. The sky literally split open as if in conjunction with the drama of the match.

Cricket is incredibly striking. The different bowling styles are explosive and elegant. Spin bowling, one technique of delivering the ball to the batter, resembles the plié in ballet. Fast bowling, a kind of furious wind milling of the arms, is terrifying and transfixing. The cricket uniform, which has stayed much the same over the past one hundred years, trim and striking white all over with the optional sweater and hat, is so dignified, so noble. Anyone who grew up with cricket takes for granted what those regal uniforms can do—they create kings—and I want this image for America.

Madeleine Hunt Ehrlich is a documentarian and a candidate for a master’s in fine arts from Temple University. Her work explores themes of physicality, violence, masculinity, and identity within Caribbean American and urban space.