Adult situations seen through children’s eyes have long been popular in Japanese literature, creating unique perspectives on difficult phenomena: nuclear war in Barefoot Gen, urbanism in Akira, or media frenzy in Battle Royale.

In reality, as fertility rates plummet and childhood psychology issues take over the news, there’s a sense that Japan’s literal future is at stake. Bullying and the cognitive mysteries of spectrum disorder have created a pandemic of hikikomori (shut-in disorder) and cases of seemingly arbitrary school violence.

Manga author Taiyo Matsumoto’s work is not known for having a political agenda. His manga worlds describe a para-terrestrial reality that doesn’t depend on physics or news items. Works like Number 5 take place in outer space; his longest and critically most visible work, Tekkon Kinkreet, depicts a Tokyo spliced with Medellín.

In his latest work, Sunny, Matsumoto has created a personal elegy that, while not explicitly political, prompts a closer look at the social welfare issues described in the narrative. Matsumoto’s manga story takes place in the Mie Prefecture, the name Sunny comes from the old Datsun the kids play in. Rich with images of urban melancholy, Sunny is like Matsumoto’s other stories, but with the added layer of being true to his life. He only recently revealed that part of his childhood was spent in a similar orphanage in Kansai while his mother worked on her career as a fine artist.

Originally serialized in IKKI magazine over 2012, Sunny is a collection of stories about orphans from the Hoshinoko Gakuen, or Star Kids foster home. Bespectacled Sei is the newcomer, not more than ten years old and obsessed with baseball. He physically guides the reader through the process of joining a foster ward, including the Beckett-esque conviction that his parents are coming back any day now.

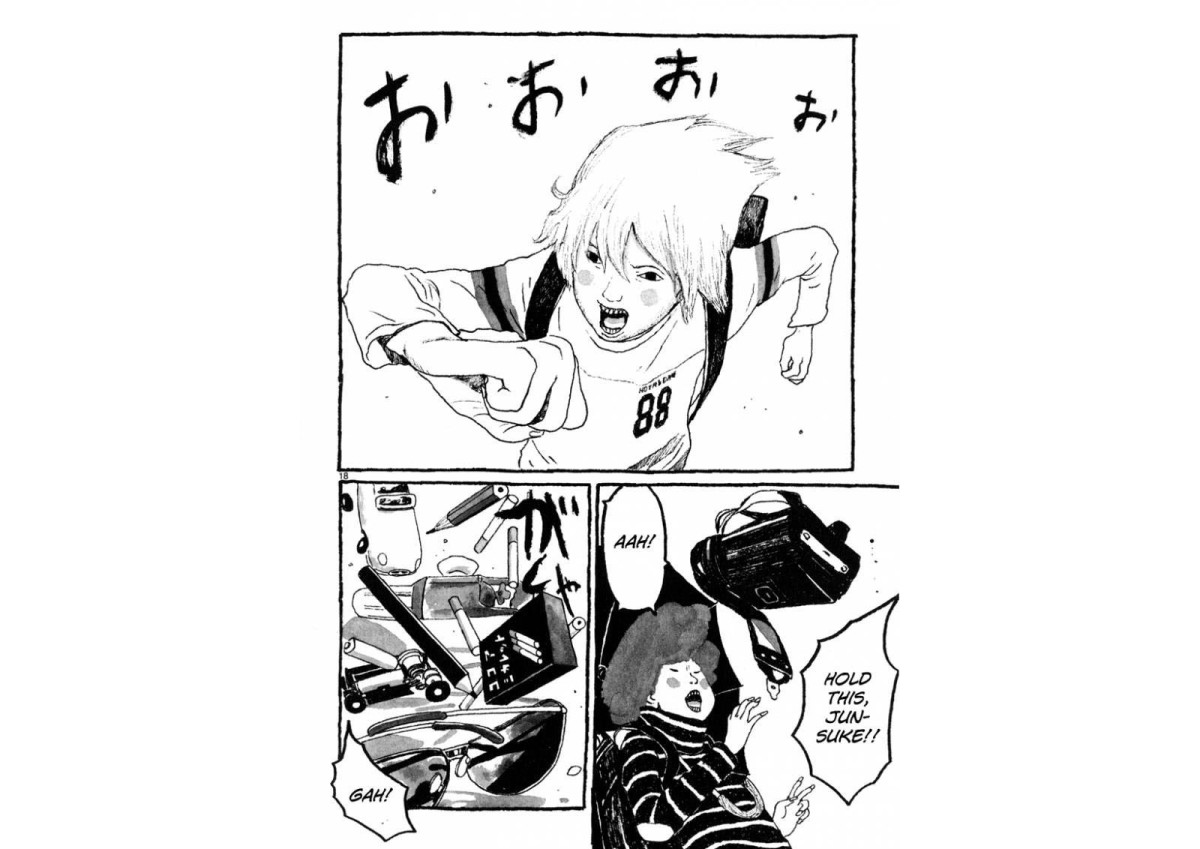

There is Junsuke, half Sei’s age and a petty thief. Kenji, the son of an alcoholic deadbeat father and one of the oldest orphans, is a high school senior debating dropping out just months before graduation. Megumu, an impressionable teenage girl, confronts her fear of mortality head-on with the discovery of a dead cat. Taro is the youngest, a toddler whose narrative inhabits a unique magical realism populated by a talking Shiba inu, a gentle giant, and a lot of four-leaf clovers. Taro ends the novel by getting lost in the last chapter of Sunny, leading his peers on a baby-hunt successfully ending at a Shinto Shrine.

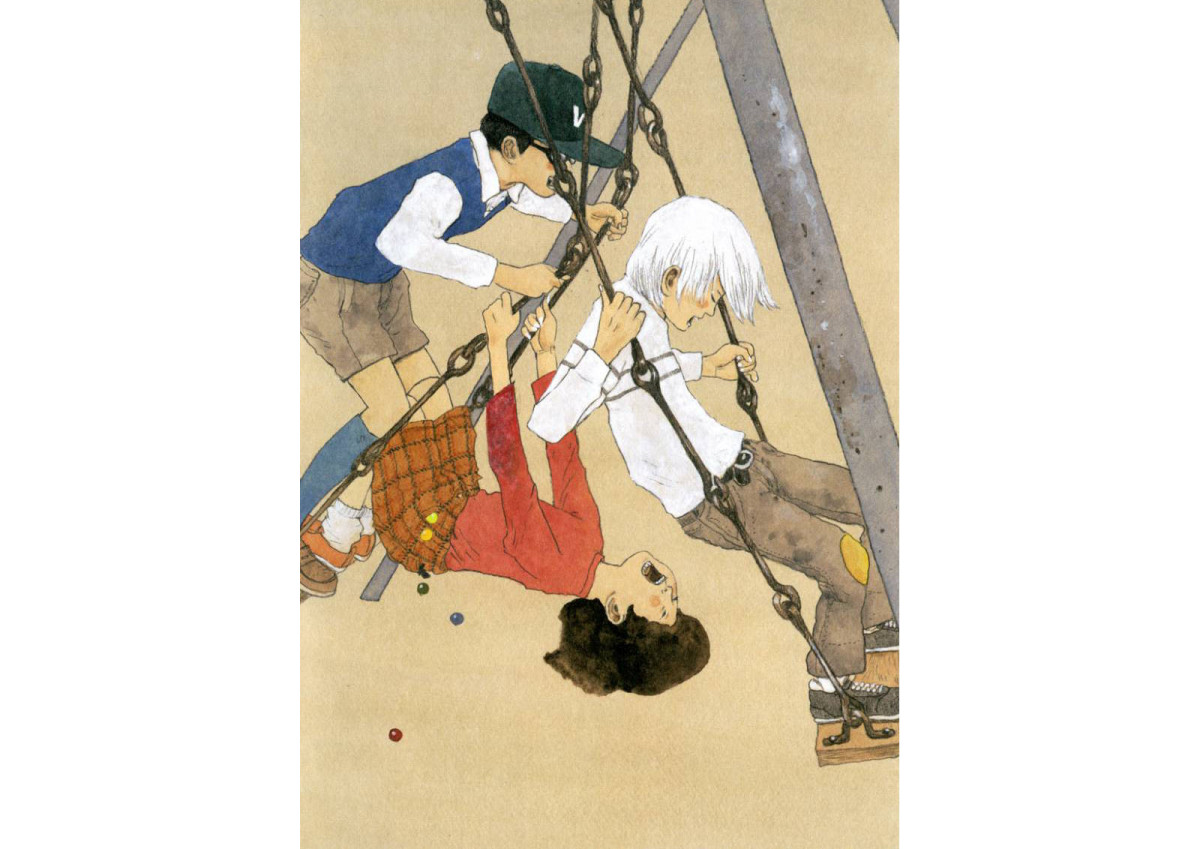

Readers will no doubt feel the terrifying urgency of being a lonely child, those feelings tempered only by the barometric vacuums they inhabit. The “cover orphan” is Haruo, also referred to as Shiro, which means “white” because his hair has prematurely grayed.

Matsumoto mentions in interviews that he was not able to draw himself as the main character, nor was he able to imbue any supporting characters with characteristics of people other than himself. However, Haruo’s heartbreaking dialogue is unavoidably sincere and forces one to compare him to the author.

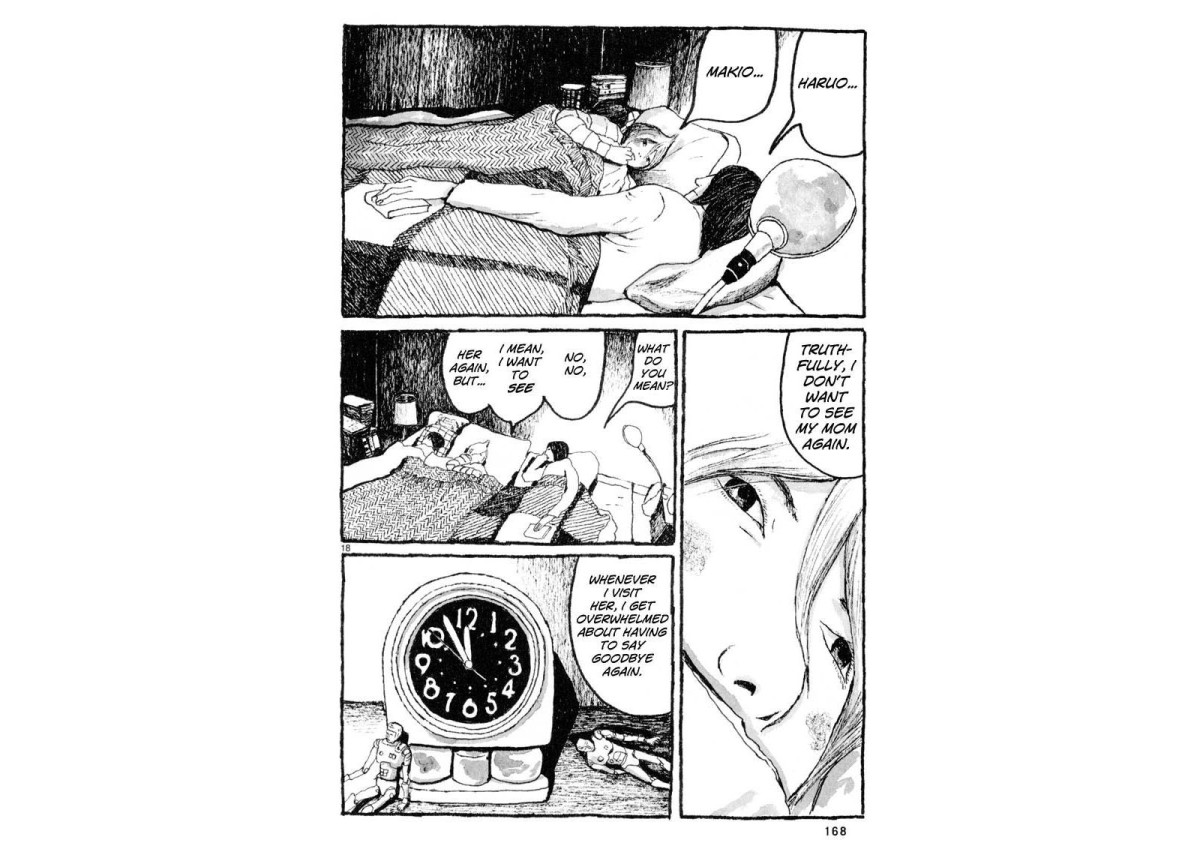

In his most direct confrontation, Haruo confesses to an older visiting graduate of the home—Makio—that he does not want to see his mother whom he misses.

Haruo: No… I want to (see her)… But I don’t want to.

When I see her, I think about when I hafta say goodbye, and I feel my heart’s gonna pop.

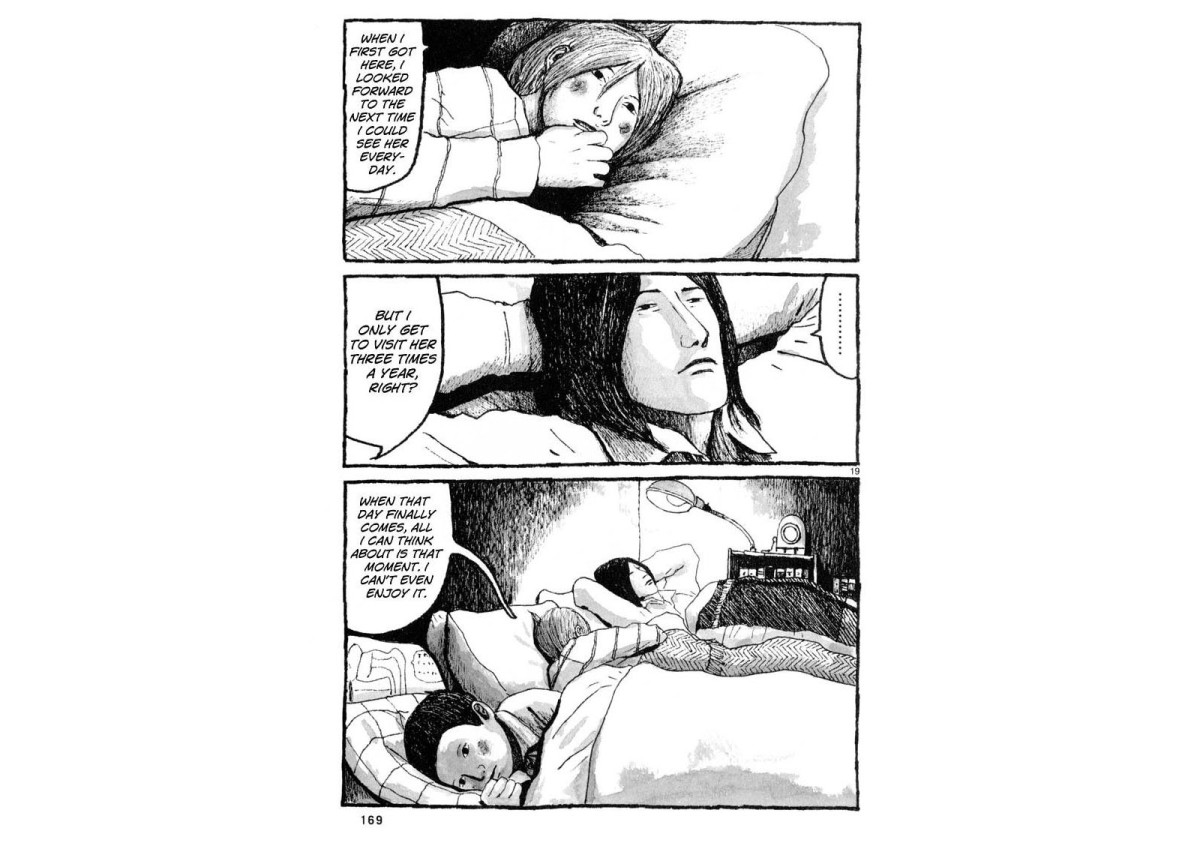

At first, I used to dream about her next visit every day…

But there’s only three visits a year, right?

And halfway through that’s all I can think of, Y’know?

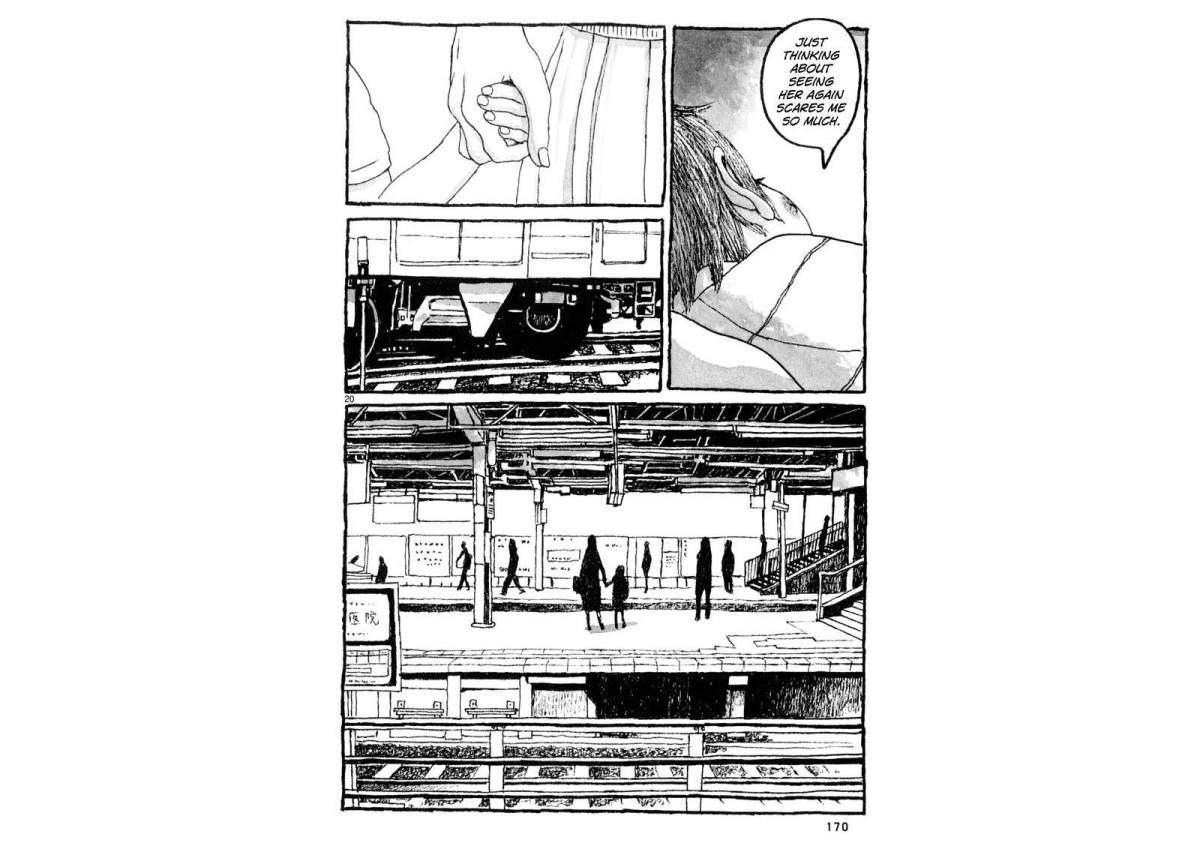

Now I’m scared just thinking of the next visit…

In this scene, Sei is depicted pretending to sleep, but is wide-eyed as the dialogue transpires behind him. Later they share their feelings over a round tin of Nivea face cream, a trinket Haruo keeps on him to remind him of the smell of his mother.

I spoke to Matsumoto about his experiences in foster care and the significance of his latest graphic novel at the Toronto Comic Arts Festival, where he was a featured guest.

“I don’t know why I felt compelled to write this,” he said, “but it was important to do it. It was important for me to take on this challenge… I’m sure children who are raised by their parents have their own issues and problems, and I wouldn’t say I grew up necessarily misfortuned, but I think there’s a particular set of things you grow up with in a foster home. That’s what I wanted to depict. I can’t say exactly why. It’s something only someone who grew up this way would understand.”

As with Matsumoto’s past works, especially in Tekkon Kinkreet, Sunny follows its child characters with either melancholic hesitation or panicked urgency. In Tekkon, depictions of the homeless urchins protecting their slum against foreign invaders make childhood violence palpable, yet in the quiet moments when those children observe the city, they are endearing.

“Looking back,” says Matsumoto “I remember a kid from the home who was so sweet, so nice. It was always amazing to me how kind he was, and that’s when I realized I was screwed up. I honestly believe my personality was totally screwy.”

And yet he insists his work, as fixated as it has been on the mischief of children in crisis, is not allegorical but merely drawn from an inexplicable penchant for drafting kids.

“I’m not sure why I draw these things, but I know I’m good at depicting children. I like drawing them, to be sure.”

It’s difficult not to compare Matsumoto to his own characters. Child-like in stature and demeanor, his hair is uncharacteristically gray for a forty-something, and his observations tempered. He loves Katsuhiro Otomo (creator of Akira) and Stanley Kubrick, but Sunny is more like a Terrence Malick film. A.O. Scott, in his review of Tree of Life, characterized Malick’s “changing interior weather of a child’s mind” as honest and accurate.

Matsumoto’s work can be likened to this same atmospheric fidelity. Even as we talked, Matsumoto insisted his personal life not be confused as the substance of his fiction-cum-memoir. And while the basics of Matsumoto’s private life are common knowledge, like Malick’s, he is not keen on marking parallels to them, preferring the diffusion of fiction.

Regarding his own childhood, I asked when he ceased to throw shoes and whip trees. When he stopped being mischievous.

“When my mother came back, I became a good kid to convince her to stay.”

Anne Ishii is a writer and editor based in NYC. She is most recently the producer of the book The Passion of Gengoroh Tagame: Master of Gay Erotic Manga, and is the Editor-in-Chief of Paperhouses. You can find her writing at ill-iterate.com