On November 6, the Jewish Museum in New York will open Unorthodox, an exhibition that brings together work by an international group of fifty-five contemporary artists. Turning an eye toward practitioners who operate outside the traditional conventions of the art world, the show will feature works that don’t quite fit into a singular art-historical tradition, and which borrow widely from a variety of sources—pop culture to politics, cartoons to historical tragedy.

Inspired by the age-old Jewish rite of discussion and debate, the exhibition brings together pieces that disrupt the typical museum experience and confronts viewers with imagery that is variously alarming, surprising, funny, thoughtful, and complex. “The field of art is generally believed to be an open and enlightened place, full of creative autonomy and artistic freedom,” says Jens Hoffmann, deputy director of exhibitions and public programs. “While that can be true in some small parts of it, the reality is that artists’ creative compulsions and productive itches are regularly subject to innumerable rules, mindless bureaucracy, and countless regulations, codes, and conventions, which together constitute systems that dictate how art is made and viewed.”

Over the past few years, Hoffmann and exhibition co-curators Daniel S. Palmer and Kelly Taxter sought out unknown or barely known artists who questioned what Hoffman describes as “art’s elitism and hierarchies” and “the unspoken societal rules governing how to behave in general,” but who were nonetheless creating world-class art. “During our initial research we looked at myriad countercultural figures and phenomena, such as anarchists, fetishists, art forgers, criminals, evangelists, journalists, comedians, philosophers, educators, the avant garde, reality TV, and Internet trolls, to name just a few,” says Hoffmann. “All of them traversed the very fine line between art and everyday life, or between fact and fiction.”

Ultimately bringing together artists from diverse backgrounds and multiple generations, the exhibition features more than 200 pieces, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, and multimedia works. Exploring the many manifestations of the word “unorthodox,” the works sheds light on, among other things, politics, identity, gender, violence, and trauma.

“To stage an exhibition entitled Unorthodox in the context of the Jewish Museum might seem provocative,” says Hoffmann. “The title does not refer to a critique of religious orthodoxy, however; rather, it speaks of orthodoxies in the plural, meaning anything and everything that is culturally, socially, or politically normative…. The most interesting moments of subversion are when artists or cultural practitioners work with all of their might to invert these norms. Art, after all, can be a brilliant means to probe previously unquestioned truths, and to allow unorthodox concepts to infiltrate orthodox systems.”

Below, Hoffmann, Palmer, and Taxter provide commentary on some of the most compelling works that will be on view, ones that, they say, “inspired us, that made us curious, that were energizing—that made us burst out in hysterical laughter or cringe at the sheer irrationality of it all.”

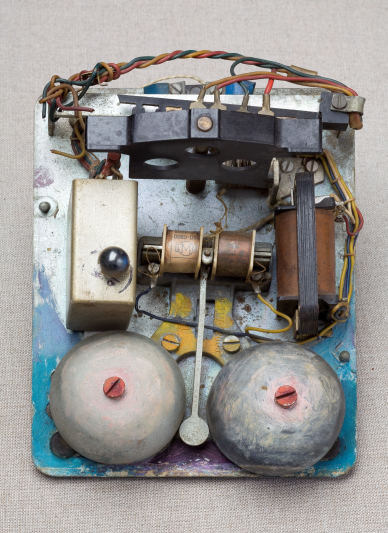

Erna Rosenstein witnessed the murder of her parents and other horrors during World War II. She survived by using various aliases and carrying fake documents bearing Christian names. These disturbing events became inspiration for her work, which calls upon a language of Surrealism and distortion of found objects, such as in this small, untitled assemblage artwork. Here, she exposes and alters the interior mechanisms of a doorbell, adding paint and rearranging forms in a way that disrupts our expectations of this banal object and serves as a protest against official state cultural policies.

William T. Vollmann traveled to Afghanistan in the early 1980s to help the Mujahideen fight the Soviets, has taken drugs with prostitutes in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, and survived sniper attacks during the Bosnian War. He wrote a seven-volume “symbolic history” of violence and freedom in America, nearly died of hypothermia in the Arctic Circle, and recently discovered that the FBI once suspected him of being the Unabomber. Alongside his abundant literary output (he generally publishes three substantial books per year), Vollmann creates thickly impastoed paintings with intricately carved frames that capture different aspects of his female alter ego, Dolores. He views his own cross-dressing and the art he makes about it as research and an exploration of femininity. “Not only am I physically and emotionally attracted to women,” he writes, “I also wonder what being a woman would be like.”

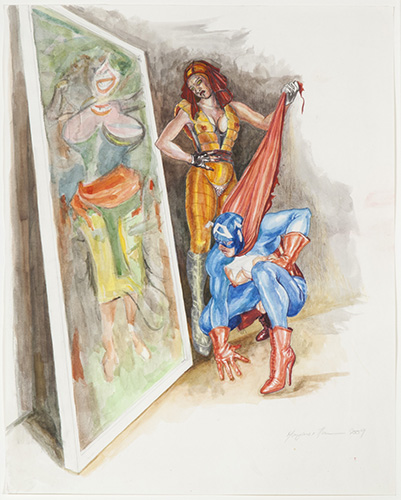

In 1970 Margaret Harrison founded the London Women’s Liberation Art Group, which advocated for women artists’ exhibitions and rights. Her first solo exhibition in London in 1971 tackled sexuality and gender issues. Included in that show were drawings of popular comic-book heroes and other pop-cultural icons such as Hugh Hefner and pin-up girls. The male figures had breasts and other feminine features; Hefner wore the “bunny girl” uniform of the servers at his Playboy clubs. Citing indecency as the cause, the police shut down Harrison’s debut after one day; the authorities were clearly threatened by representations outside the heterosexual norm. As with this 2009 work, she continues to revisit these decades-old images; the issues that spurred them remain, to her, unresolved.

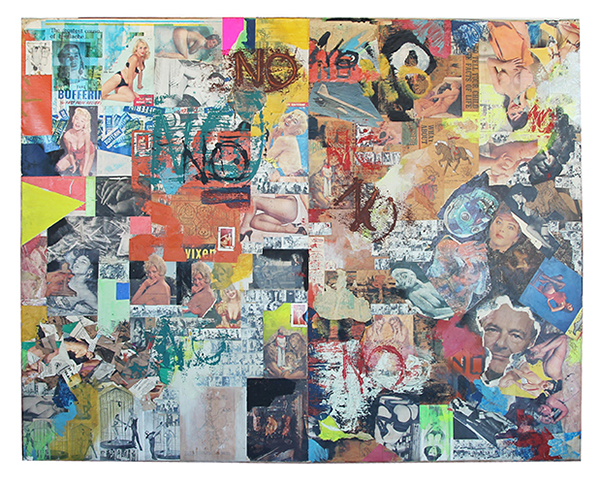

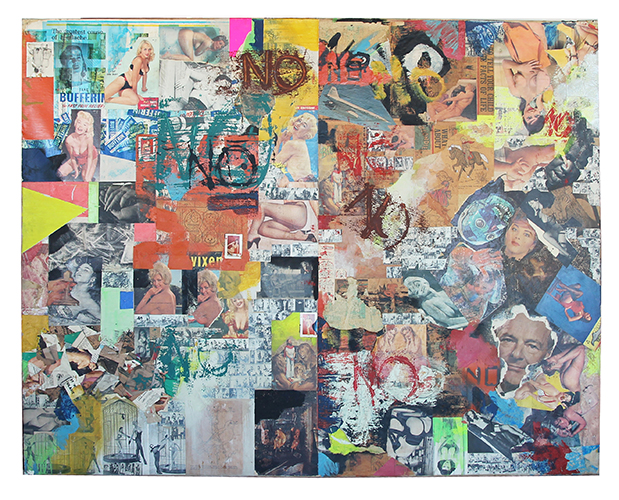

Boris Lurie’s highly charged political works meld the sacred with the profane. In his “Big No Painting” from 1963, for example, pornography is overlaid on Holocaust imagery. In other works, a Star of David becomes intertwined with a swastika. These pieces, which often include the exclamation “No!” scrawled across them, condemn the flattening of violence into pure imagery. Lurie’s art was a working through of his own traumatic experiences as a Holocaust survivor and witness, as well as an act of resistance against the numbing effects of consumerism, capitalism, and war.

Bunny Rogers has numerous websites authored by a string of alter egos: Emr006, emr007, emr008, Catgirl462, catnip4, Serineana, Biff Brannon, Muffy Summers, and bunrogers. This collection of pages and personae is a scattered self-portrait, a mode Rogers often employs. She practices the art of immersion, slipping into different versions of herself, friends, or characters from TV, books, and art history. She fosters a strange intimacy with her subjects and, in turn, reflects on how peculiar closeness has become in the wake of social media. For the series Self Portrait as Jeanne D’Arc, Rogers insinuated herself into a character from the cult cartoon television series Clone High.

Cyrus Kabiru’s childhood home was adjacent to Nairobi’s massive and overflowing Dandora dumpsite, a landfill located just two miles outside of the Kenyan capital’s center. The first thing he saw every morning was garbage. This inspired him to expand his concept of the cast off and thrown out—a theme prevalent in his work—to encompass not only objects, but also to address Kenya’s changing relationship to individual freedoms, industry, and reliance on foreign manufacturing. His series of found scrap-metal bicycles draws parallels between the individualistic life of an artist and the freedom engendered by locally made goods and community.

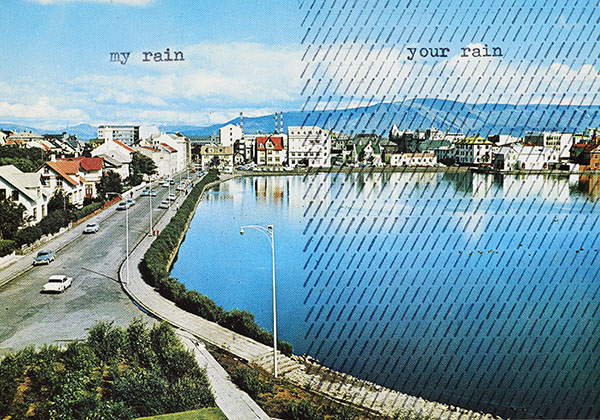

Endre Tót studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest, but came into conflict with official Socialist Realism doctrines and was expelled. To overcome the state-imposed isolation he faced in Communist Hungary, he would send his art through the mail to the West. “My Rain—Your Rain” (1971-78) is part of a series of works created on found postcards, and features a rain-like pattern made by repeatedly typing a slash. He tempers this minimalistic, almost banal repetition with a critical edge through the further addition of humorous statements and political critiques written directly on the images.

Austė had few acquaintances as a child, and did not learn English until she began school at age five. Inspired by the Lithuanian folktales, poetry, and plays passed down to her from her parents, she created her own elaborate costumes and enacted rituals in the woods around her suburban Detroit home. These childhood ceremonies later informed the Cococello Club, her performance troupe, for which she wrote, directed, and costumed a series of productions presented in East Village nightclubs in the 1970s and 1980s. Echoing this history, her paintings of sylph-like women, as in the painting above, with their feline companions, jewel-covered skies, and castle-dotted landscapes, are rich with character, fantasy, and fashion.

Max Schumann’s paintings are made of acrylic on cardboard. In lieu of his signature he paints a price—$1, $10, $!00, $1,000—in the lower right-hand corner of each piece. He often paints the same image multiple times, but assigns different prices to the nearly identical versions. Schumann and fellow artist Dale Wittig founded the artist-activist practice the “Cheap Art Collective,” which plays on the idea of value and quality to highlight, as in this work, intersections between the mass media, gentrification, war, economics, and culture.

Gülsün Karamustafa has witnessed sociopolitical upheavals and military coups, and was caught in waves of forced migration between Greece and Turkey. Her passport was revoked between 1971 and 1986, and at one point during the 1980s she was imprisoned by the Turkish military. Informed by these experiences of physical and cultural displacement, she explores notions of hybridity, economic and political mobility, difference, orientalism, and postcolonialism through the lens of art history and the language of Turkey’s folk customs and aesthetics. Her works on paper poetically commemorate the noble efforts of her compatriots who participated in these political causes. Here, a woman is shown endlessly sewing bright-red Communist flags, underscoring Karamustafa’s interest in the steadfast role of women in these struggles.

To contact Guernica or Abby Margulies, please write here.