“Subverting always makes sense if it doesn’t feel like a rule, but if it allows also recreation, which is the same as re-creating.” —Paulo Bruscky

I first encountered Paulo Bruscky’s works in 2013 far from São Paulo, my home, at the show Paulo Bruscky: Art Is Our Last Hope at the Bronx Museum. Bruscky was born in Recife, in the northeast of Brazil, in 1949. He began making art during a hard moment for Brazilian politics: a military dictatorship that lasted from 1964 to 1985. What was important in Bruscky’s early practice was that he was also looking for, and ended up finding, answers to repression by making art meant to experiment, using creativity and imagination to subvert an adverse condition—essentially, starting from scratch. He called this the process of unlearning. Seeing his early pieces was a way of digesting the June 2013 protests that I hadn’t experienced. Bruscky also helped me understand how the events of the 1960s still resonate now.

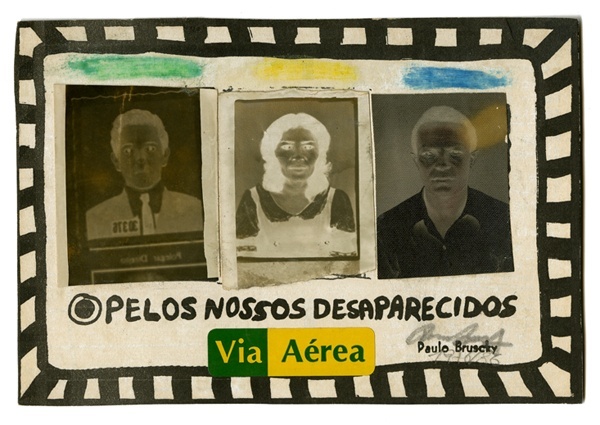

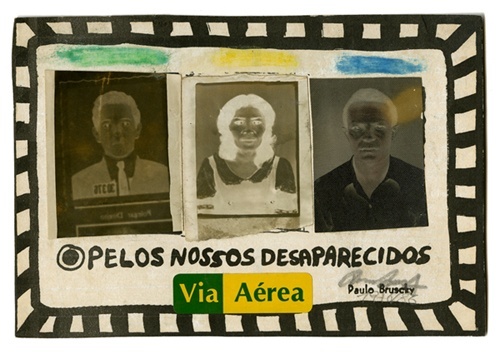

It’s been fifty years since Brazil was taken over in a military coup; the result was over twenty years of dictatorship. During the 1970s, militants, students, and intellectuals were persecuted, tortured, sent into exile, or killed. Brazil was flooded by ideological hostility from the right and the left. Up in Recife, Bruscky was going against the flow of control: he often worked alone, doing performances in the public space, testing and regularly surpassing the limits imposed by the regime. His first works were part of the “mail art movement,” whereby artworks were sent via the postal service, to spread the word about the oppression.

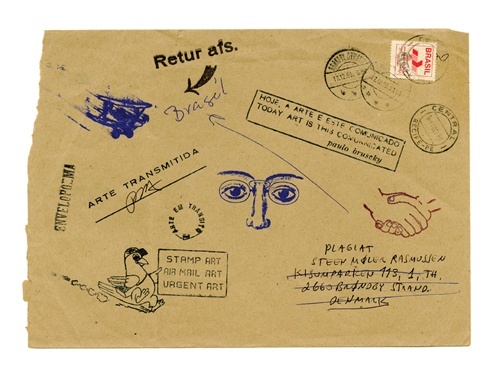

What remain from Bruscky’s works of that time are envelopes that seem to be expressing discontent and grief about missing friends, but also convey quasi-enigmatic imagery: puzzling eyes, flying men, guns, skulls, or holding hands that float on the paper. From that moment up until the 1980s, Bruscky started to create an aesthetic and conceptual universe of his own. But instead of being overwhelmed by grief, Bruscky worked within the tragic-comic, and with the absurdities of Brazil’s political condition.

Recife, Brazil

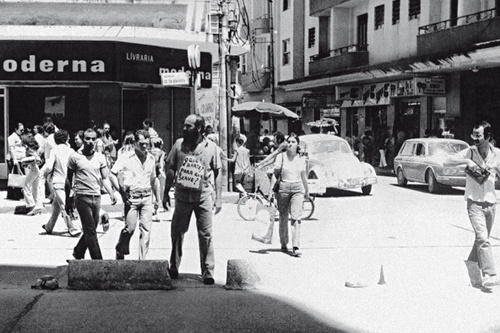

In 1978, Bruscky wandered around Recife like a sandwich-board man wearing posters that asked in bold type, “What is art? What is it for?” After strolling across the streets, or merely sitting on plaza benches, Bruscky would stand for hours as a live display, facing pedestrians from the window of a local bookstore. These questions were genuine for Bruscky, who was trying to discover what an artist could do, and what art could do, amid so much repression. Before that, in Funeral Art (1971), with a bit of dark humor, he announced his own funeral as an artist, transporting a coffin with canvases to a gallery. Local newspapers were amused and called the action an exhibition. At the end, spectators were handed prayer cards and candles. It could not have been a more literal interpretation of Roland Barthes’s The Death of the Author, the seminal text that challenged the notion of authorship, and with which Bruscky was familiar. For him, this newfound and freeing perspective on art became a tool against political violence: he realized that the ephemeral art he was making could be both conceptually and politically liberating.

At a time when Brazilian artists were still influenced by the European concrete art (a movement that praised the rational and essential elements of each technique)—or in Recife, by even more traditional art forms—and the practices of Helio Oiticica and Lygia Clark, for instance, were just starting to be assimilated, Bruscky’s works were aligned with the anti-object currents of the Fluxus Movement.

During those days, Bruscky was jailed and interrogated, and his house was invaded by the military. Not only because of his ideology, but because of his art. Bruscky’s pieces are distinct, eccentric, and also a bit clumsy and funny. Though he was being persecuted, what came up in Bruscky’s works was not anger, but a silence, and as he himself has said often, a kind of unlearning.

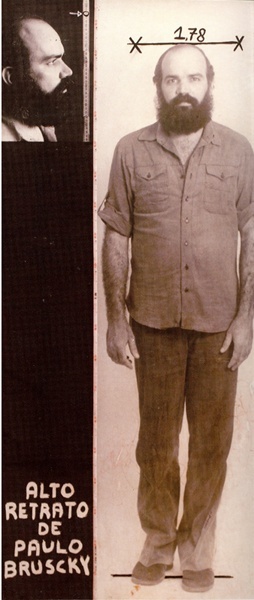

The use of language within artworks is also characteristic of conceptual art. Bruscky created poems and games with images and words, mostly in Portuguese. His humor is often found in simple combinations of the title of the work and a visual element. “Poetic Line” (1981), for example, is composed of those same words and a red twisting thread that is the aesthetic counterpart to the text: an exact, non-metaphorical, “poetic line.” “Tall Portrait” (1978) is a black-and-white self-portrait marked with his dimensions; in Portuguese, self-portrait is auto-retrato. But Bruscky substituted one letter for another, so what we have is an alto-retrato, or tall portrait. The piece seems to simulate a type of criminal record, perhaps criticizing the way Brazilian activists were being treated by the regime. In “I’m Pickling Myself” (1974), both the text and image are amusing. Although Bruscky uses a similar image for this self-portrait, he now smiles at the viewer, and floats like a pickle inside transparent glass. The Bruscky who, in “Tall Portrait,” was being measured and aesthetically depicted as blacklisted, appears in another universe, as if a consumable mini-artist ready to be taken down from a market shelf by the hands of a laughing child. Bruscky intertwines fiction and nonfiction, maybe to see how far art can go and to test reality itself.

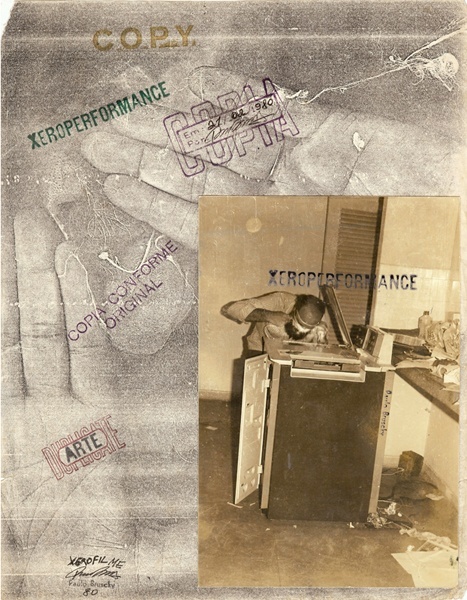

Of all of his work, X-ray and xerox self-portraits may be the most intriguing. “Autum Radium Retratum” (1978-2013) is an X-ray of his skull as a self-portrait and “Xeroperformance” (1980) is a series of photocopies of Bruscky making faces by pressing his face against the glass of a copying machine. They look like bizarre, hypochondriacal experiments with the limits of now outdated machines. Bruscky worked in a hospital for a while, and contact with this kind of technology clearly influenced him. The gestures Bruscky makes in these self-portraits defy the rational way of handling these devices and become a subtle act against authority.

These early works are active and fruitful, with implicit layers of sadness, inertia, and an isolation, desolation, and awkwardness that, at times, are funny. As I walked to the subway, leaving the Bronx Museum, I tried to imagine what Bruscky must have experienced in the 1960s. We have a lot to learn from him. When last year one million people took to the streets of Brazil, for a brief moment the march was strong. The protests were contradictory, but most were spontaneous and not fabricated by political parties. That moment held a fragile, but promising, freedom, the same spark that is found in Bruscky’s works—a kind of unlearning about ideology, ideology that before the protests was frozen for many young Brazilians. A lesson to be learned: it is more important to shout, even if the solutions are still unclear and sides are still not chosen, than to embrace a mandatory silence.

Tatiane Schilaro is a graduate student in the MFA program in art criticism and writing at the School of Visual Arts in New York City.