Visual artist Sarah Crowner’s work has been described as many things: lyrical, hard-edge painting, primary abstraction, non-painterly. Curator Gary Carrion-Murayari coined it “Personal Modernism.” She has been declared a painter, a sculptor, and an installation artist during her career, but none of these terms feel comprehensive enough, nor do they do the artist, or her work, justice. Standing in front of Crowner’s abstract sewn paintings or her large-scale tile installations, one is filled with a sense of modernism’s profound influence on her work as well as with her deft ability to harness the energies of the natural world.

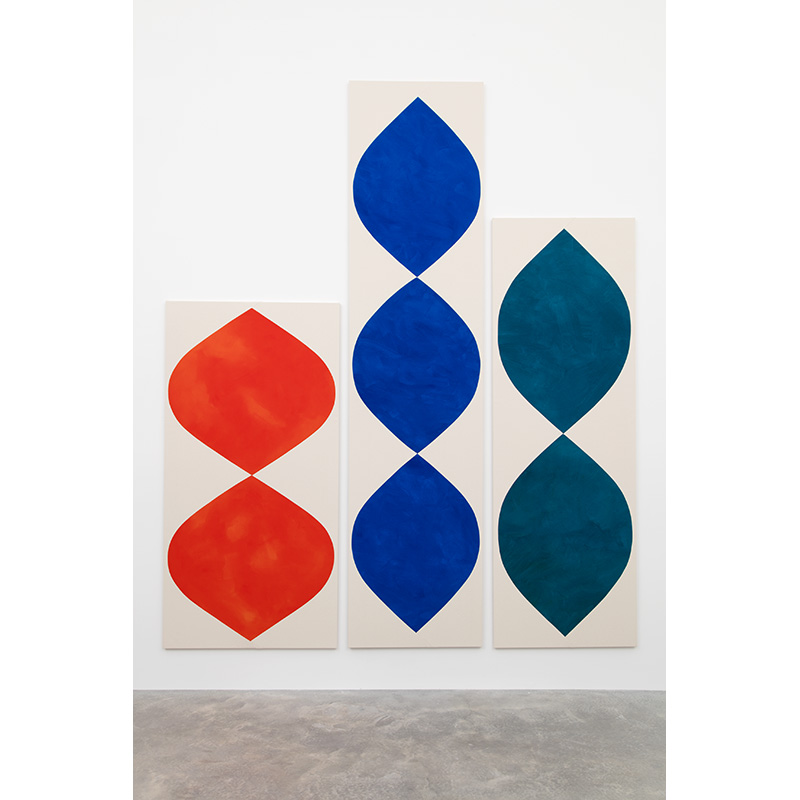

This spring, Crowner’s work will appear in two major shows; Beetle in the Leaves, which runs from April 16 through February 2017 at MASS MoCA (Crower’s first museum show in the US) and Plastic Memory, which opened May 13th at Simon Lee gallery in London. Both exhibitions feature the artist’s sewn paintings—cut-up pieces of raw and painted canvas, reconfigured and re-stitched to form a new surface—as well as new tile works, installed both on the floor and hanging from the walls.

The fluidity with which Crowner navigates different media—painting, sculpture, and ceramics—reveals a vast range of influences: from hard-edge painting and Op artists like Victor Vasarely and Bridget Riley—who inspired Crowner’s large-scale black and white geometric installation, Continuum, 1963, shown at the 2010 Whitney Biennial—to the magazine editor Alexander Lieberman and decades-old issues of Harper’s Bazaar. These oscillations are what makes the artist so hard to classify and, perhaps, is what has kept her from the spotlight for so long.

Crowner was born in Philadelphia and attended graduate school in New York, but she spent much of her early life on the West coast—Santa Cruz, Oakland, and Portland—where she took up painting. “I spent all those hard years by myself, making bad art,” she told me when we met in her soon-to-be-abandoned Gowanus studio. She is moving to a larger studio in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and speaks about those years with residual consternation and amusement. “I still work a lot,” she tells me. “I really don’t want to ever stop.”

That seems improbable. Crowner is interested in not only creating new modes of painterly expression, but in the studied reinterpretation and elevation of existing art histories. In all her mediums, she’s able to capture, in the words of Bridget Riley, “the dynamism of visual forces.” It is Crowner’s ability to cross genre, to collapse time, even, that makes her artistic voice at once challenging and essential.

—Elizabeth Karp-Evans for Guernica

Guernica: You have two shows opening this spring. Is it difficult to present two bodies of work at the same time?

Sarah Crowner: It seems like, the last six years, there’s always been another deadline, but I’m always working towards something. With these two shows, there are plenty of cross-references. For example, I’m using a similar tile pattern in both shows; one in fired terra cotta, and one using hand-painted cement. Also, the paintings for the show in London come out of the process of making the paintings for the show at MASS MoCA.

Guernica: Your work is often informed by the physical space of a gallery or museum. Did the spaces in Massachusetts and London influence these shows?

Sarah Crowner: The MASS MoCA show is an example of a physical space that I had to reckon with that was very limiting, but also inspiring, because it was not a clean white cube. It’s raw ceiling beams, rough brick walls, and floorboards. It looks a lot like this studio, in a way. There’s this history that’s embedded in that building and I wanted to draw on that and pay attention to that.

The show is a lot about patterns. I’m making a tile mural and a tile platform, both large-scale, originating from a pattern that was just discovered by a group of young mathematicians. The platform is one thousand square feet and the wall mural is twenty feet by ten feet. Both are made out of a particular pentagon design. The sewn paintings in the show are made using patterns as well, similar to the way that a tailor would use a pattern to make a suit.

Guernica: How did you come to use patterns in your paintings?

Sarah Crowner: Living in Santa Cruz, the Bay Area, and Oregon, I was always taking hikes and going on a lot of solitary walks. I didn’t make this connection until recently, but I think the forms, colors, and beauty in nature that I experienced are suddenly coming up in my work now. Back then, we didn’t have iPhones—there was a lot of wandering around just looking at things. I think that time was a real gift.

Artwork exists in relation to the world around it, so at MASS MoCA I thought about the interior—the beams, the bricks on the wall—behind the paintings. When you’re standing on this huge tile platform, your experience of looking at the paintings and these beams is going to be very different than if you were standing in a perfectly white gallery space. Here, you’re standing on this geometric abstraction, on a painting in a way, and it changes the way we receive art. I find it interesting how pattern informs your reception.

Guernica: You’re using pattern as a way to recontextualize familiar space?

Sarah Crowner: Yes, with this show in particular. I really paid attention to the architecture: where the beams were, where the floorboards met with this very old glass, the windowpanes and ancient windows. There’s a grid in there. In order to make that show, I found a new pentagon pattern that was recently discovered. The form can only be repeated with its mirror so it’s not a singular form or tile that’s repeating; it’s the double. I thought that this was a brilliant but really subtle concept: something that can only be repeated with its partner. As a way of regenerating. It’s very natural.

I also painted on the cement tiles rather than using a terracotta glaze. Glaze can be sprayed or brushed on, and when you fire it, different things happen to the color that can be stunning, but accidental. With this new work, I wanted to paint decisive and gestural brushstrokes, to relate the work to the paintings.

The end result is kind of a like a vibrating painting.

Guernica: Did you make the tiles yourself?

Sarah Crowner: I worked with a factory in Morocco. I had a mold made, and we made about two thousand tiles. I went there with my assistant, Nicky, and we got a bunch of house paint and painted a few different colors all over. They look very brushy, kind of white-washed in a way. Some I left raw. Then they cured and were sealed and shipped to Massachusetts, where they’ll be sealed again and placed in the floor and grouted. The end result is kind of a like a vibrating painting, the way the brush strokes in one tile might be going one way and the brush strokes in another tile might go in a different direction, but they all run up against each other. It was really an attempt at interruption of gesture.

Guernica: What is it like to work in an environment like Morocco when you’re envisioning a show in Massachusetts?

Sarah Crowner: It’s a big leap of faith, because one can only imagine how the work will look in the space. I didn’t know what the tile platform was going to look like until it was finished. I rendered it on the computer, and I think I know what it’s going to look like, but I had never done it before; no one has. This pattern, as far as we know, has never been tested on a surface, because it’s brand new.

Guernica: Your paintings also relate to this idea of bringing together different parts to form a whole, constructing something that’s visually brand new.

Sarah Crowner: Exactly. Earlier, I had all these different pieces of a cut-up painting on the floor. It’s a lot of me saying, “Does this work this way? Does it work that way?” and arriving at a pattern. Then I sew it together. I’ll stretch it, and then maybe slice it up again. It might end up smaller than originally intended, or back in pieces. The process has become very lengthy.

Guernica: Why did you begin to work with tile and ceramics?

Sarah Crowner: In the very beginning, I was working in New York and I wasn’t feeling like I had found my voice in painting. I was very frustrated with painting, although I love paint, and I love working with paint. I felt that there was something missing, and it was something tactile—I wanted to get into the work, to touch it, to manipulate it. I met somebody who told me about a ceramics residency at Hunter.

I stopped painting entirely, and I started making these handmade clay vessels, these pots that were sculptural. Firing them, playing with glazes, and having a really good time; I made a great body of work and ended up showing it. My first solo show in Berlin was these handmade, blobby, bottomless vessels. I began thinking about craft as it relates to modernism, and as it relates to a particular art history that I was interested in at the time, from the 1950s and 1960s.

I was thinking, how can I bring craft and modernism together, but still be painting? I loved doing ceramics, but I still wasn’t finished with painting.

Then I saw a Vasarely painting from the early 1950s, which was really weirder than what he did in the 1960s; slightly ugly and really fascinating. I saw a black and white reproduction of it, and I thought, “I want to somehow cut that up and figure out how what makes it work.” What’s a painting made of? It’s fabric. It’s paint and fabric, pretty much, on a support. So what if I painted on canvas and cut it up, and then stitched it back together? I was thinking the hard lines could be a sewn line instead of a painted line. I thought that intersection of the high art of painting, and then the making of the functional object, sewing, could be somehow collapsed in doing the work that I’m doing now, the sewn paintings.

Manipulating material and working with clay really brought me back into painting in a different way. I began constructing paintings, and making paintings that are objects. You might not even call them paintings, because they’re something else even though they’re made of paint and canvas.

Guernica: They’re construction. The whole process is very constructivist.

Sarah Crowner: They’re construction, yes, or building. I think that art history can be a medium that can be manipulated in the same way that a material, like paint or clay, can be. You can work with your hands; you can touch it. What if we could open art history books and pull the contents out and stretch out the forms, reverse the forms, collapse them?

It has become something between painting, wall, and floor.

Guernica: That seems to be happening with craft art, connecting it with modernism, with fine art; it means something different than it did sixty years ago. Did you intended to draw on this collapsing when you started making the tile pieces?

Sarah Crowner: I didn’t really intend it until I arrived at it; I’ve been pushing it ever since. At MASS MoCA, I am showing a tile mural, but the feeling I am interested in is a kind of “lifting” a tile floor up and hanging it on the wall, elevating it and treating it as a painting. It has become something between painting, wall, and floor.

Guernica: Is part of changing the viewers’ experience of time, slowing it down, a conscious choice to eliminate the frame?

Sarah Crowner: When you’re standing on a tile floor and you’re looking at a painting, you’re really receiving the painting in a different way than you would if you were in a white cube space, or something more generic. You’re standing on a composition. You’re looking at a composition. It’s using your body to receive the painting: it’s a bodily experience.

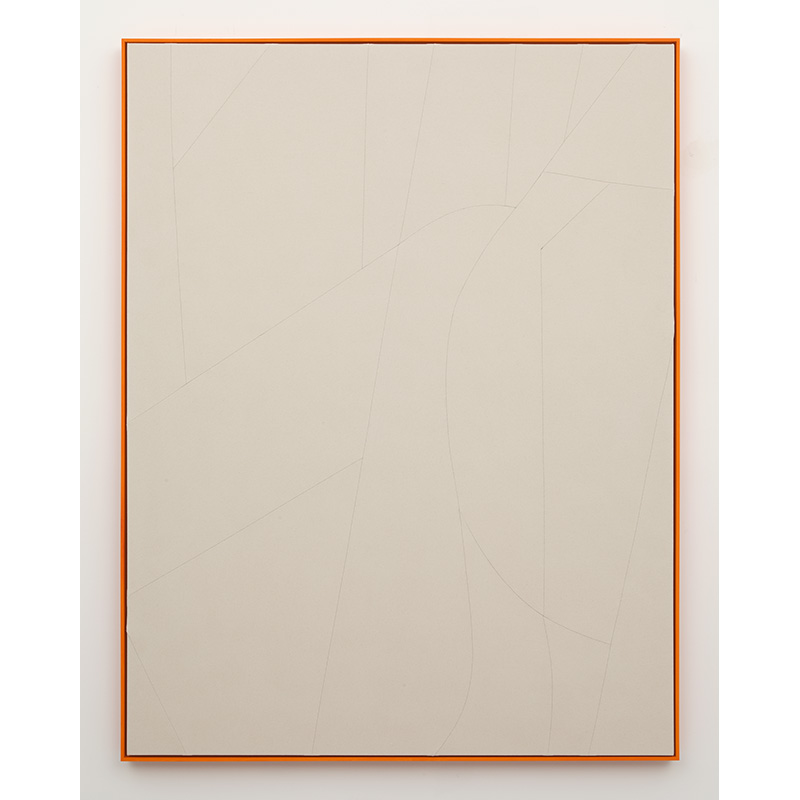

Guernica: You get compared to Bridget Riley but there’s something more organic about your painting; a looser geometry to it. Do you think this is due to the physical nature of constructing the work?

Sarah Crowner: There’s a real quickness and spontaneity to my work—especially with the new work, which is coming out of taking a form and then slicing it up and reorganizing it—that’s not really planned out. I have referenced Bridget Riley directly. I saw a photograph of her standing in her own installation, almost like a spiral room of zigzags. It’s a famous picture, and these zigzag black and white forms envelop her. Making those paintings was an attempt to look at the way a work has been photographed, not at the painted forms themselves.

Here, I was studying a reproduction, not studying the actual Riley art object. That’s where I feel like I have the license to have a little bit more fun. I think if you’re going to spend your life doing something, you should enjoy it. Thinking about painting and making painting gives me a huge amount of joy.

Guernica: Your works are very tactile and draw inspiration from the natural world, but technology also plays a large role. Would your work be different in a different time?

Sarah Crowner: Definitely. Think about if it were the late 1970s and we were in the art historical moment of pattern and decoration. There were artists at this time thinking about decoration in a way that was against compositional painting. Pattern is non-compositional; it’s one shape repeated again and again. It’s nonhierarchical. I think the feminist artists of the pattern and decoration movement were saying that’s what makes it essentially a female thing: perhaps composition is male, and non-composition is female.

I also use Photoshop a lot. I use my camera, I use scanners, I use Amazon or eBay to find the early 1950s Harper’s Bazaar where the Ray Johnson backdrops were printed for the first time. I made a whole series of paintings based on these Ray Johnson backdrops he painted for Harper’s Bazaar in 1957.

Guernica: You take a lot of inspiration from publications.

Sarah Crowner: I love art books. I thought if I wasn’t an artist, I would have my own art bookstore. I have spent a lot of time in libraries. When I was growing up in LA, I would go to the UCLA library. In San Francisco I snuck into the San Francisco Art Institute library. There were Xerox machines. It was a different way of gathering information. I was reading a lot of books—Agnes Martin’s writings, reading a book about Jessica Stockholder—and reading a lot about women artists in particular.

I saw that it was possible to have a life as an artist, and although there are so many factors at work, mostly one has to show up every day to the studio.

Guernica: You moved from the West Coast to New York for grad school. Was it easier to find an artist community?

Sarah Crowner: The thing about New York, which is great, is that it’s such a practical education. I got a job at Printed Matter to support myself through Hunter College. I found that this was a better education than graduate school, because I was working day-to-day with real artists making a medium that wasn’t just precious—it was a book. I ended up starting the bookstore side of Dexter Sinister, which was a basement publishing project in Chinatown, handling production. I worked for the Oldenburgs. Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, before she passed away. I was their studio manager for a few years. Then I worked for Rudolf Stingel for a few years.

I saw that it was possible to have a life as an artist, and although there are so many factors at work, mostly one has to show up every day to the studio. It sounds very simplistic, but so much has to do with showing up. I gained a lot of practical knowledge in New York: You have to make a living, so what are you going to do? You should try to do what you love.

Guernica: What’s your show at Simon Lee going to be like?

Sarah Crowner: We’re going to have about seven or eight paintings and a tile platform using the same pentagon pattern, but using glossy white glaze on the floors. It’s a long, skinny gallery, and the platform goes halfway through the gallery, so the viewers have to walk on it. Then there’s going to be a wall piece, a tiled mural. At some point, you’ll be standing on a composition and looking at another composition that relates to the one on the floor. It’s about asking viewers how they’ll receive each work. One, you walk on, and the other is treated as a painting, but they’re the same.

I’m really interested in the audience’s reception of painting and what painting is, and what it can be. It’s possibilities. I wonder if people will try to touch the tile mural. I hope they do, but we’ve all been taught you’re not supposed to touch anything that’s on the wall if you go into a gallery. Yet it’s the same material installed on the floor.

Guernica: Are you surprised by the way people react to, or act in, your installations?

Sarah Crowner: In a gallery in Brussels I once made a platform that was made of raw MDF. It was a simple platform that covered the entire footprint of the gallery. You had to step up about seven inches and you were on the platform, it was like a stage. People were so nervous just to step up! Several paintings were hanging on the walls, but the only way the viewer could really look at them was if you were standing on this simple raised platform. People were afraid to do it at first because they felt they were on stage. They wondered: What’s going to happen? It’s this interesting psychological space that changes when you feel like you’re on stage.

Guernica: Presenting a stage, constructing your paintings, making books; your work is very much production-based. Is part of having a show come together bringing these immersive, laborious experiences into the space as well?

Sarah Crowner: For me, being an artist is about doing. Of course there is also thinking, reflecting, contextualizing. But for me, thinking is doing. It is a way of understanding through making. It is also a solitary act, even though you may have assistance sometimes. You have to go into your studio and spend a lot of time by yourself, and be okay with that.

To contact Guernica or Elizabeth Karp-Evans, please write here.