The doctor who arrived in my wife’s recovery room to perform our son Sebastian’s circumcision was a mix of Foghorn Leghorn and Huey P. Long, a gentleman from another age. A pale, portly man in a white dress shirt and black suspenders, he introduced himself formally as the “attending physician who would perform the procedure” and walked me down the hospital’s hallway toward the room where my two-day-old son lay, oblivious.

“If I may, young man,” the doctor asked me, “were you present yesterday for your wife’s cesarean section?”

Darcy’s first pregnancy had been mostly smooth until we found out that the baby was breech. While it isn’t unheard of for OBGYNs to attempt breech deliveries, the likelihood of dangerous complications for both mother and child can be heightened considerably under such circumstances, and a C-section is often recommended unless the baby flips in time. And so came a tragicomic parade of techniques we undertook together to turn the baby right-side down, including the two of us visiting an acupuncturist with a stoned assistant; Darcy doing headstands in a pool; and, as a last resort, me singing and humming through a paper towel roll into her groin to coax the baby down through some sad human proxy of echolocation. In the end, though, he stayed just where he was. A C-section was scheduled for a week before Darcy’s due date, but she went into labor three hours before the surgery. As she tested Darcy’s dilation ahead of her now-emergency C-section, the maternity nurse, “Baby — you got feet dangling out your vagina!”

I was present for the surgery, holding Darcy’s hand through the twilight of her meds. I saw her red guts, which looked oddly lovely, and I fumbled with the scissors to cut the blue cord. Now, standing in the hallway with the circumcision doctor, I told him as much. I felt exhausted, raw, and openhearted. “Well,” he continued, in his genteel drawl, “what you experienced yesterday watching your wife’s Caesarian section is called sympathy. What you are about to experience watching your son’s circumcision is called empathy.”

He meant it to be funny, but I was struck by those words then and still think of them often — not only as they relate to myself, but also in reference to all men who are in some manner of sexual partnership with menstruating persons. When liberal men express outrage at the naked anti-abortion rhetoric and barely constrained misogyny of the American conservative movement, is it sympathy or empathy that we are expressing? If sympathy, why does our outrage stop there? If empathy, what are its limits?

In spring of 2018, with Sebastian on the cusp of his fourth birthday, Darcy and I were delighted to discover that she was, again, pregnant.

From the beginning, there were warning signs that everything was not as it should be. At first we were content to rationalize away or ignore these signs. The almost immediate extreme nausea and crippling abdominal and lower back pain Darcy began to experience just several weeks out from that first double-line; the bizarre irregularity of the test results themselves, with one test coming up positive and the next negative; Darcy’s increasing certainty that what she was feeling through the early spring of that year was nothing like what she had felt gestating Sebastian.

Darcy’s doctors demurred, questioning her pain. And though I myself never disbelieved it, exactly, I found myself swayed by the assurances of the medical staff. I also discovered that there were limits to my ability to empathize. I could tend to Darcy when she was throwing up on her knees for an hour on the bathroom floor, then remove my hand from the back of her neck to take my son to a neighbor’s pool party. I could lie next to her as she writhed in pain in a tangle of bedsheets, and still manage to tell her that everything would be fine. She was in a very different place: “Don’t forget me,” she pleaded at one point. I knew she was in awful pain, but the pain wasn’t mine and I wished it away.

Darcy is no pushover. For almost a decade, she has been an activist for increased access to reproductive rights in the Gulf South, where we live, and nationally. She is also a Unitarian Universalist minister. More recently, she has channeled these commitments into becoming a PhD candidate in history at Tulane University, focusing on the fraught intersection between reproductive health, rights, justice, and religion in the United States. Not only has Darcy long served as a compassionate advocate for the reproductive rights of others, but she is attuned to the dictates of her own body and a forceful advocate for herself when it comes to her own medical care. If Darcy’s body knew, she knew.

When she was finally admitted to the emergency room on a steamy New Orleans morning in mid-May, it didn’t take the doctors long to ascertain what had occurred to us both several times but what, in our guarded optimism, we had failed to recognize: the pain Darcy was experiencing was due to an ectopic pregnancy that had ruptured the fallopian tube. Within an hour of this diagnosis, she would undergo emergency abdominal surgery to contain the rupture itself and prevent further blood loss and possible death. “When you had your C-section four years ago, that was to save your baby’s life,” the obstetrician on call told Darcy and me in the anteroom to the OR, an eerie echo of what the doctor who circumcised my son told me years before. “This surgery will be to save your life.”

Our faces crumpled, as though conjoined.

As vivid and wrenching as my memories are of that day, there’s so much on Darcy’s end that I’ll never begin to understand — like the transvaginal ultrasound she received from a callous, incompetent radiation tech in a far corner of hospital who, through some fluke of communication between hospital admittance and Darcy’s obstetric team, left her twisting in stirrups while congratulating her on a future that would never be. I can only guess at the profound melancholy my wife must have felt to miscarry in this way, hounded by the thought that she might lose her life.

When I got the call that Darcy was, indeed, okay, manic relief and elation washed over me. But what I felt most was an overwhelming sense of powerlessness in the face of my wife’s subjugation to the functions of her own body. And that terrified me.

Darcy had lost the fallopian tube. She’d also lost a lot of blood. Before getting off the call so I could contact Darcy’s family and my own with the news of her surgery’s success, I asked the doctor if she thought it would still be possible, or advisable, to try for another child in the future. “Probably, sure,” she said blithely. “Might just take a little while.”

When I came a few hours later to pick Darcy up from the ER recovery room and help her outside to the car, she incrementally swung her legs from the side of the bed. She hobbled toward me, devastated, overjoyed to return to her life.

Although Darcy recovered physically from her ordeal in a matter of weeks, it took more than a year for the trauma of what she’d experienced to subside. I had also been traumatized by the event, but not on the same molecular level. There were terrible nuances to Darcy’s experience that continued to elude me, even when she explained them. That she’d been in abnormal, crippling pain — pain she was told she didn’t feel. That she’d been cut off from the people she loved in a dizzying moment of needing them most, sunk into anesthesia. That, viable or not, she had lost a wanted pregnancy.

In the meantime, Darcy had begun to receive chaotically itemized and miscalculated medical bills from the hospital. Time and again, on the phone with her insurance company and with the hospital’s billing department, she was asked to recount in excruciating detail the circumstances of the ectopic pregnancy itself and the emergency surgery she underwent to contain it. To this day, Darcy cannot open an envelope from the hospital without her fingers trembling. For days she will set them aside on the counter, these totems of doom that bear her name.

When, in the fall of 2019, we discovered that Darcy was pregnant again, we were thrilled but cautious. The first trimester found us whimsical at times, contemplative at others. Finally, on a warm winter night on our New Orleans porch, surrounded by frolicking neighborhood kids, we told Sebastian. He was a little confused but elated: “I’m going to have a baby brother!” For him, it was uncomplicated, this creative process of which he was the fruit.

Darcy’s third pregnancy, like her first one, went smoothly. Masked and nose-swabbed this time, Darcy gave birth again, in the same hospital, by another C-section. Again, my wife’s hand held in mine. Again, her gorgeous maze of guts. Again, the baby’s cheek on hers before I was ushered over to scissor the cord. The baby urinated gloriously onto my arm. The surgical team stitched Darcy up, resealing the scar from two previous cuts. We named our second son August after August Wilson, the American playwright. His skin was as soft and as sweet as a crepe.

Two days home from the hospital, Darcy began to experience painful bloating in her abdomen. It was subsequently diagnosed as a hematoma, the result of excess blood from the C-section seeping into her intestinal wall. She would have to be readmitted to the hospital.

I was home with the kids, one of them two days old. Those forty-eight-hours were strange, terrifying: I could barely sustain my frayed nerves with a drink, so scared of what would happen next, that I would have to drive, to flee, to sustain this faint thing trembling in my arms. When the baby wasn’t asleep in the depths of his sling, I taught him to bottle-feed. To replenish his milk, we drove to the hospital, where Darcy was pumping alone in her room. These bottles of milk were ferried downstairs to the hospital’s driveway by one of several of the birthing center’s lactation staff. Sometimes I gazed up at the hospital’s windows in the hope of seeing Darcy, but the glass was tinted. I couldn’t see through.

I decided to get a vasectomy in the winter of 2021, nearly a year after our second child was born, almost two years to the day since Darcy’s ectopic pregnancy.

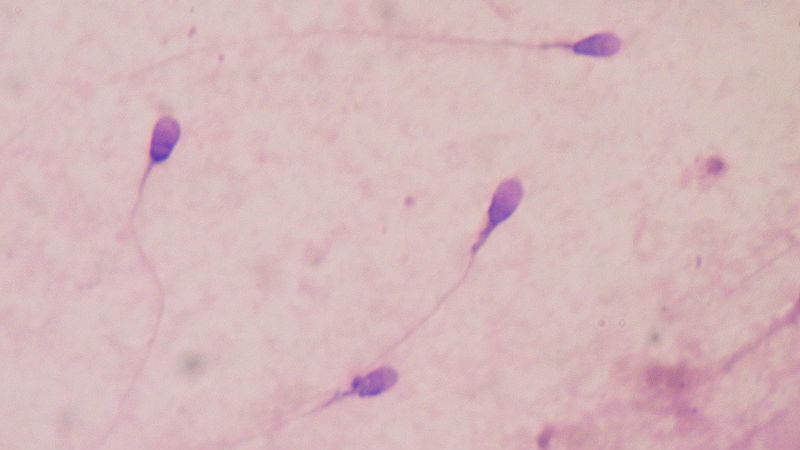

I went to see a urologist and told him what I wanted. He asked if I was sure, only once, without judgment or coercion. Then he walked me through the procedure itself: an hourlong, same-day surgery under local anesthesia, followed by a single follow-up appointment to determine the efficacy of the surgery by “tumbling” my sperm to look for live ones. He asked if I had a partner and, if so, if she had given her consent.

Although spousal consent isn’t legally required for a vasectomy, urologists consider it to be “good practice.” In principle, encouraging but not requiring spousal consent also applies for those seeking tubal ligation, hysterectomy, or abortion, in the states where it remains accessible and legal. In practice, however, it is disproportionately more difficult to access these common healthcare services than to get a vasectomy. Women have reported being denied tubal ligations or hysterectomies if they do not have spousal consent, and have been made to undergo extensive psychological evaluations and write essays defending their choices. It is no longer difficult to imagine, in a post-Roe world, that these double standards of consent could become enshrined in law. So while it is strange to conceive of such a straightforward procedure as a vasectomy constituting a form of resistance, that is the world I live in.

Apart from a “consent” form, which I did indeed have Darcy sign, all I would need on the day of the procedure was the athletic protector I would have to wear for support throughout my recovery, and someone to drive me home from the hospital, as I’d be in no condition to drive myself.

I shook the penis doctor’s hand.

A month or so later, a nurse gently shaved my testicular region. The local anesthesia was a prick in the balls. When my urologist came in and made the incisions — one on each side of my scrotum — through which he would sever and cauterize the vas deferens that conducts sperm up through the penis, I felt minor discomfort. Some tugging and pulling. He biopsied sections of what he had found and then stitched me up again.

At home, I iced my balls with frozen peas. After two days I was on my feet. In another two weeks I was jogging. Two months after the surgery, I went in for the follow-up visit where they “tumbled” my sperm and uncovered no stragglers. A month after that I received the bill: a single sheet, cleanly itemized, billed to insurance, which cost me a total of five hundred dollars.

The dissonance between Darcy’s reproductive experience and mine was so sharp and profound it would verge on parodic had the danger for Darcy not been so dire, so deadly. I want to acknowledge this, and also, to push past it.

It can be dangerous for men to let the gap between women’s experiences and their own undo them, stranding them — stranding us — in a place of paralyzed inaction that morphs, over time, into complacency. In my vasectomy, I found a way to be empowered by the terror I felt at Darcy’s pain and peril. And while I would like to be able to say I had a vasectomy to ensure the well-being of the person I love, that is magical thinking. Getting a vasectomy allowed me to feel I could do something to make my partner less vulnerable to the vicissitudes of her reproductive system and the systemic patriarchy that seeks to exploit that vulnerability. Considering all my wife had gone through — what so many women go through to live the lives they want, whether or not those lives include children — a vasectomy seemed like the only meaningful response. In fact, like the only response: There was no other choice I could make as a man.

Today, there is an increasingly large part of me that feels it is essential for me — for all men — to continue pushing back against oversimplified definitions of sympathy and empathy, with their stultifying limits. Instead, I want to equip myself with what political scientist and author Terri Givens defined as “radical empathy,” a process by which we “[move beyond] walking in someone else’s shoes and [take] actions that will not only help that person, but will also improve our society.”

Vasectomies won’t appreciably narrow the gap in severity between men and women’s reproductive experiences and outcomes. But for men, considering vasectomy can be a step toward a more radical, vulnerable, and actionable empathy. Along with unconditionally supporting the right to abortion — through activism, donation, voting for candidates who support reproductive rights, and having direct conversations with those in their lives who would prefer to reduce people with uteruses to what they can gestate — a vasectomy is an acknowledgment, sealed in discomfort and inconvenience, of the autonomy and physical well-being that menstruating people put on the line every day in the course of making reproductive decisions, small and large. If sympathy requires our outrage, empathy demands our action.