By Angela Boskovitch

Offensive words’ social stigma often have no known origin. The meaning and acceptability of linguistic expressions evolve together with society, however, and new uses appear. In Egyptian colloquial Arabic, the word A7A, a common transliteration of the Arabic letters ‘alif, haa, and ‘alif, is prohibited from being broadcast, published, printed, or distributed in any formal way because of its perceived vulgarity. But for a generation questioning social norms, socio-economic hierarchies, and political passivity, this word commonly meant to evoke a sense of objection, frustration, and contempt is being used more than ever.

Artist Bashir Wagih conducted a photographic study into the many uses of A7A, pronounced AHHA, that became part of a multimedia exhibition held in March at Cairo’s Photopia photography gallery.

“We had some threats before the opening, and some people came just to object to it being here,” says Wagih, matter-of-factly, despite the potential violence he faced for exhibiting A7A Portraits. “I explained to people that this was something philosophical. It’s about questioning what we believe in the present that has to do with the past.”

A7A and its social implications have no known derivation, explains Adel Iskandar, a media scholar and lecturer at Georgetown University who has researched the expression.

Because of the term’s versatility, A7A can absorb practically any meaning the person saying it wants it to—from disgust and anger to shock or surprise.

“With contemporary colloquial language, it doesn’t really matter where the term originated, so long as it has utility,” he explains. “It was considered the kind of term used by those of lower standard, although not necessarily lower class. It’s very jarring to the ear. It severs the comfort and harmony of human communication.”

Because of the term’s versatility, A7A can absorb practically any meaning the person saying it wants it to—from disgust and anger to shock or surprise.

According to Manfred Woidich, Professor Emeritus of Arabic at the University of Amsterdam, an expert on Egyptian dialects and co-author of the Wortatlas der arabischen Dialekte (Word Atlas of Arabic Dialects), A7A is “an interjection which belongs to Egyptian ‘baby-talk’”—linguistic forms like onomatopoeia that small children acquire while developing their mother tongue. According to Woidich, A7A is one of three similarly sounding expressions grouped together in the authoritative A Dictionary of Egyptian Arabic: Arabic-English by Martin Hinds and el-Said Badawi. “A7A and similar terms are in common use in Egypt, and presumably have been so for ages,” Woidich explains. “It seems to have an onomatopoetic origin. As to its vulgarity,” he continues, “it is more or less because the term has sexual connotations too,” in its allusion to the supposed sound women make during sex.

In literature, the term has historically been used only by a very small group of radical writers to speak to the plight of the poor and downtrodden, and even then it was written in the dialogue of their characters, rather than the narrator’s voice. The profane satirical poem “Kos Omeyaat” by the late leftist poet and playwright Naguib Sorour, which makes frequent use of the word, could only find publication in the former Soviet Union. In June 2002, a Cairo court even handed down a one-year sentence to Sorour’s son, Shohdy Naguib Sorour, tried in absentia for possessing and distributing the poem online and transgressing public morality. A7A has never been uttered in a film, with the exception of it being spelled out as “A-7-A” by Ahmed Mekky in the 2008 film H Dabbour, a comedy that uses plenty of objectionable language.

“Using the term today means you object to something or are angry, or something is extreme, intriguing, or captivating,” says Iskandar. “It’s the limit. It’s a term that pushes the limits and sets the limits at the same time.”

It’s this use as an interjection of strong and sudden emotion that most interests the artist Wagih. The idea for the current exhibit grew out of his own desire to understand the nuances in facial expressions that accompany utterances of A7A. Upset after an incident with some friends, Wagih photographed himself and noticed that in his own facial expression of A7A, a look of frustration dominated. “I also shot my assistant’s A7A reaction, but his facial expression was very different than mine and I wondered why,” he says. His own theory is that since “no one knows what it [really] means… Its use is different from person to person.”

“Objection is becoming a standard practice of daily life in Egypt today…. People are using A7A all over the place online.”

A communications engineer by education, Wagih designed a multi-phase experiment to study the A7A expression. First, he met with his participants individually for an initial chat. Then, each one was invited to his studio, where Wagih asked his subjects to recall a time that day when they had wanted to say “A7A” to someone but couldn’t for fear of transgressing social norms. Wagih would then role-play the story with the participants in order to provoke an emotional reaction from them. When each person was about to exclaim “A7A”, he asked them to express it on their faces rather than say it.

“When you build up emotion during a role-play and then stop from saying the word, the emotion automatically translates to your face,” Wagih explains. “That’s when I took the picture. I showed each person the photos and asked them to choose the one that best represented how they thought they looked.”

Although some of the emotional expressions were reactions to current events, most were responses to personal experiences.

Wagih shot the photos over nearly two years, beginning in late February 2011. “Only recently have I learned more about the origin of A7A as a word for objection after meeting with a professor from Al Azhar,” he says, speaking of the university’s Faculty of Arabic and Islamic Studies. “Before meeting him, I was doing more of a social survey by asking random people what the expression meant to them.”

Among those Wagih photographed were Egyptians and foreigners living in Egypt aged eighteen to thirty-seven from different social classes and educational backgrounds. “I tried to be as diverse as possible, but I couldn’t find anyone older than thirty-seven to take part. Even if they understood the idea, it was just too much for them.”

This change in social acceptability is in part the result of a generation coming of age in a time of protest, where terms like A7A can be found everywhere.

“Objection is becoming a standard practice of daily life in Egypt today,” explains Iskandar. “People are using A7A all over the place online. It’s still not acceptable, but there’s growing tolerance. This is not because the term has taken on a more positive meaning, but because of desensitization. Things in Egypt are getting closer to the catastrophic and people have a lot more to be frustrated about. It’s on the tip of their tongue.”

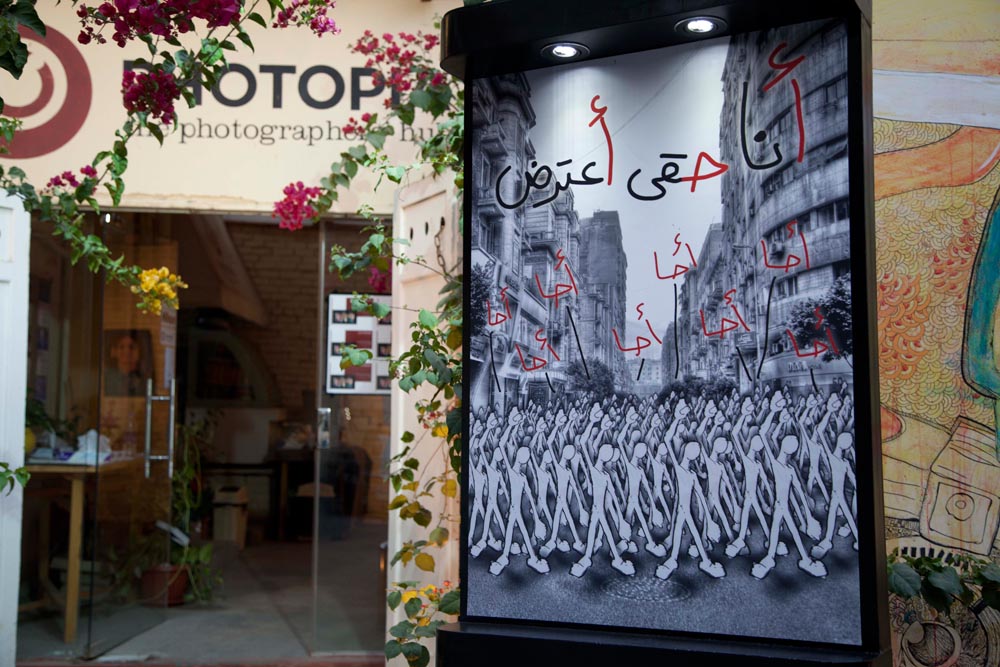

This use of A7A as an objection was portrayed in the first installation of Wagih’s three-part exhibit. In a garage space preceding the gallery’s entrance, a series of three dramatically lit, digitally manipulated hand-drawn works were arranged as a kind of comic strip—all that could be seen in the otherwise dark space—with the fourth in the series located a few paces beyond, just outside the gallery door.

The three drawings in the garage depict a portly king decreeing unjust royal orders to cries of “A7A” from his subjects, who take to the streets. One of these works directly references current events using hand-drawn protestors superimposed onto a photograph of a Cairo street. To heighten the contemporary context, actual garbage was strewn beneath the work, invoking the city’s trash-lined streets.

The final drawing in the series, which visitors encountered just prior to entering the gallery, showed protestors chanting, “I have the right to object”—words whose respective first letters in Arabic coincide with the ‘alif, haa, and ‘alif of A7A.

For the artist, the doors to the gallery served as a kind of threshold for contemplation. “Here’s where I tried to provoke people into understanding that a lot of the things we do in our daily lives are not actually ours,” explains Wagih. “They’re not spawned from our interactions or experiences, but rather from the past. The exhibition was not just about the word A7A. I want people to ask questions about our inherited experiences.”

“What really surprised me is that people found the less intense images to be more disturbing, because it meant that the person was blocking their emotion in some way.”

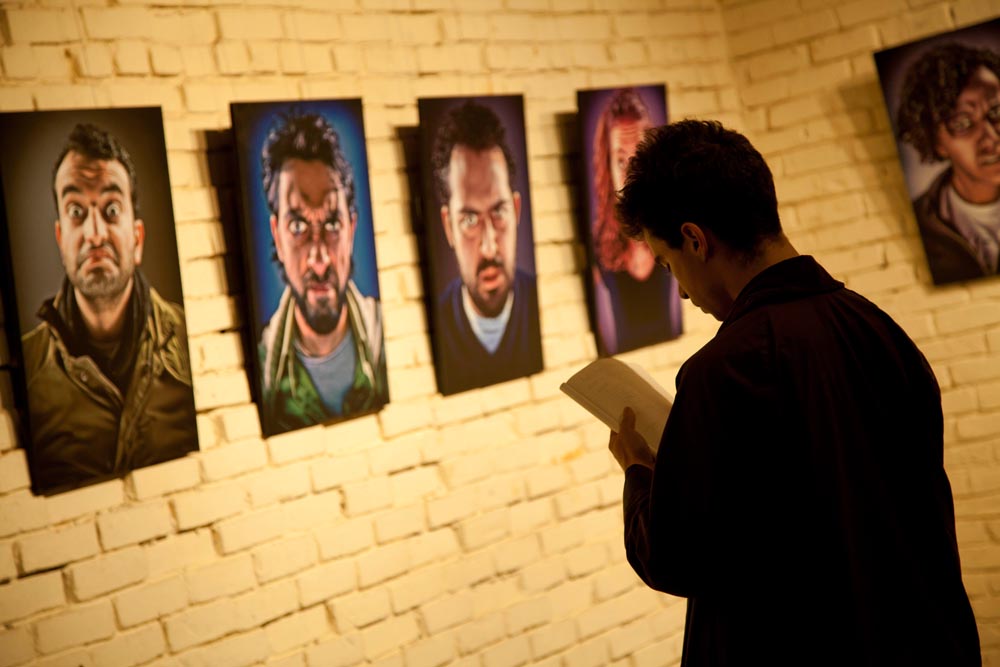

Inside the exhibition space, fourteen portraits slightly larger than life-size were hung in rows of seven. They showcased emotional expressions as jarring as the term itself.

Not content to let his study end at the photographs, Wagih was also interested in the reaction of the visitors who came to the exhibition opening. “There were men and women, a professor, youth intrigued about an exhibit showing this word. But what really surprised me is that people found the less intense images to be more disturbing, because it meant that the person was blocking their emotion in some way.”

The exhibit’s patrons were also asked to give their own A7A expression on film, posing alongside the portrait they felt most closely resembled how they perceived their facial interpretation of A7A to look.

“I wanted to know if I’d shown the full range of A7A’s uses, if everyone at the gallery could identify with at least one of the images,” Wagih adds. “I also wanted the visitors to interact with the images to break the awe of such a disturbing photo. I was surprised that everyone who took part in the video found his or her facial expressions in the gallery.”

Now that the exhibit has come to an end in the upscale Korba neighborhood of Heliopolis, Wagih plans to show it at a location in Cairo’s Downtown, the scene of protest activity, where, he explains, the exhibition will be in its natural comfort zone. He would also like to show the works somewhere outside of Egypt.

Born in Dubai, raised in Canada, and now living in Egypt, Wagih has a special interest in understanding emotion beyond the bounds of culture, and he is already at work planning a larger project to photograph facial expressions in multiple countries.

“There’s a universality about the way we express emotion,” he remarks. “Someone who worked at a shop near the exhibit was struck by the drawing of the king and came by. Although he was uncomfortable about coming in because he didn’t feel he was dressed to attend such an event, once he did he found the portraits very expressive. He’s now going to do his own research into A7A.”

Angela Boskovitch is an art director and freelance journalist writing about the arts in the social, cultural and political spaces of the Mediterranean and Middle East. Her writing has appeared in ARTPULSE (USA), Women’s eNews (USA), On Earth (USA), The Egypt Monocle, Avvenire (Italy), The Austrian Times, FRM-FrankfurtRhineMain (Germany) and DEUTSCHLAND (Germany), among others. She has worked on documentaries in Germany, Italy, Egypt and Iraq and lectured university students on intercultural communications. She also develops art and culture projects for the MENA Region.