At the end of the month, the Justice Department will grant early release to 6,000 inmates from federal prisons as part of an ongoing effort to ease overcrowding and offer redress to harsh sentencing for drug related offenses. This is the largest one-day release in our country’s history. The word is finally out: The prison industrial complex destroys individuals, families, and communities. The American justice system has proven to be anything but just, undermining the best parts of American democracy—the right to a fair and speedy trial, the presumption of innocence until guilt is proven, and the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. The system targets, entraps, and engulfs those whose lives are marked by poverty and mental illness, and astonishing numbers of African Americans and Latinos. Bolstered by the war on drugs, “tough on crime” political campaigns, mandatory minimums, and three-strikes laws, the carceral state expanded at record pace in the past few decades.

This is not the first time the nation has been caught up in heated debate about the purpose and methods of punishment. The same can be said of the early American republic, a few decades between 1786-1830 when the penitentiary in the US was born. Pennsylvania’s leading statesmen joined with Quaker reformers to overhaul the state’s penal code. The move to make punishment humane, rational, and nonviolent was inspired by two key and equally compelling forces: Enlightenment theories of justice and what we might call the birth of American exceptionalism. Elites considered the British penal code overly severe—a relic of medieval times and representative of all that was wrong with old Europe. They moved quickly and decisively to change it. The new system of punishment eschewed outright violence—no more whippings, brandings, stocks, or pillories—in favor of a term of containment and penance. In 1790, punishment became defined by a singular experience: the denial of freedom. This decision dovetailed with abolitionist efforts in the state.

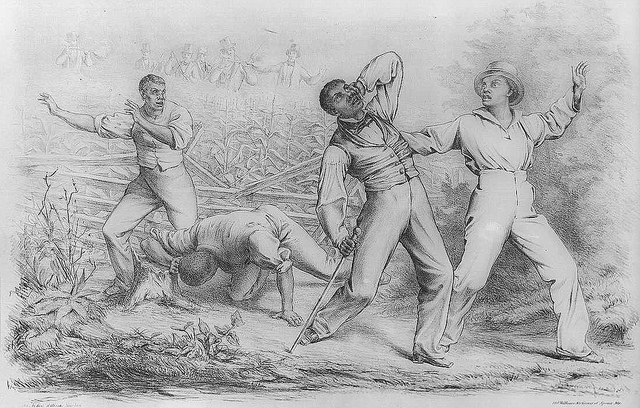

The association between crime and African Americans was established both through the language of criminality, with deep roots in slavery.

In 1780, Pennsylvania passed the Gradual Abolition Act, making it the first state to pass a law abolishing slavery. The law famously did not free a single enslaved person already residing in the state but rather promised gradual freedom for the next generation. But the state quickly became a refuge for runaways who could successfully cross into its borders. In the decades to follow, the city of Philadelphia quickly became home to the largest free-black community in the country. This era of freedom and abolition in the North—commencing eighty years before slavery would finally meets its end nationwide—is generally deemed a bright spot in the history of American race relations.

But there is another side to this story, a darker tale of our nation’s founding that confirms what now seems all too obvious: the promises of American democracy were never intended for African Americans. This exclusion was once achieved through enslavement and a Constitutional compromise that counted the enslaved as three-fifths of a person. White abolitionists including Benjamin Franklin felt the compromise was a necessary evil, that national union was more important than the freedom or human dignity of African Americans.

In the decades that followed, the criminalization of blackness served to further undermine African American claims to freedom and citizenship. Free blacks were treated terribly on the streets, before the courts, and inside the prison. The association between crime and African Americans was established both through the language of criminality, with deep roots in slavery, as well as through public discourse that was willfully colorblind and refused to acknowledge racial difference. The language of criminality was used to deflect attention from the abuses African Americans faced and served to justify said abuses. Willful silence about how a given policy or practice disproportionally targeted or affected free blacks was even more dangerous. Both were deployed to undermine African American claims to freedom, justice, and citizenship.

Slavery itself made criminals of any and all African Americans who sought freedom. African American children were never given the benefit of the doubt or treated as children in need of protection and support from state. Rather, the court system came down hard on them—especially when those deemed most powerless asserted themselves. In 1794, Pennsylvania Attorney General William Bradford, Jr., mocked the use of arson as a crime of revenge, noting that it was a tool of “slaves and children.” While he belittled them with words, it was clearly maddening to Bradford, lawmakers, and other white elites that enslaved black girls found a way to fight back against structural powerlessness. Black girls convicted of arson received brutally long prisons sentences—from five to twelve years—and many died while in prison. This was deemed a logical result of their inherent criminality and was not cause for concern among reformers.

It was one thing to be against the enslavement of a people but another thing entirely to respect their humanity and recognize their right to citizenship.

When free blacks were on trial for crimes during this period, judges often used abusive language towards them in the courts. Before issuing a verdict for a group that including both enslaved and free blacks in an 1803 arson case, the president of the court noted “their ingratitude towards the citizens of Pennsylvania, who had done so much for them.” Such condescension and infantilization towards free blacks aimed to both justify and distract from the harsh punishments issued by the state. Black elites and most abolitionists communicated their own disavowal of arson as a strategy of resistance, believing that it went too far and undermined the goodwill of liberal whites. But arson and the threat of arson were excuses to indirectly articulate what most whites already believed: African Americans were not capable of functioning within the laws of society and didn’t deserve the rights and freedom of citizenship.

It was one thing to be against the enslavement of a people but another thing entirely to respect their humanity and recognize their right to citizenship. In 1800, members of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery suggested that more African Americans attend church as a way to cultivate their finer sensibilities and as a result, encourage better treatment from masters. The logic here, though not explicitly stated, suggested that African Americans invited abuse by not being properly submissive. This approach willfully ignored the longstanding tradition of slaveholders and other whites using both extreme and subtle forms of violence against African Americans to get them to submit to their wishes. Such characterizations by white leaders who supported black freedom were damning and served to undermine the prospects for black equality in society and under the law.

By the 1810s, Philadelphia was embattled over the place of the growing free black community. Several local officials—including the mayor—introduced legislation in 1813 that would require free blacks to register with the state and carry papers with them at all times. The response of one of the city’s black elites, sailmaker and businessman James Forten, reveals how bad things already were. Forten made several powerful points, although one resonated more loudly than the others. He claimed that society needed to take greater responsibility for the education and empowerment of a group of people previously enslaved. He complained that the constable, night watchmen, and jailors had already shown bias against African Americans and could not be trusted to carry out the laws. But Forten would only go so far in his critique of the system and he distanced himself from those who committed crimes, calling for policing authorities to clamp down hard on people of all races who broke the law. He wrote, “The villainous part of the community, of all colours, we wish to see punished and retrieved as much as any people can.”

Forten embraced a “tough on crime” approach toward free blacks in order to preserve the freedom and dignity of elite law-abiding citizens like himself. There was no reason to believe the state needed Forten’s encouragement to do what it had already undertaken—he was not to blame for the growing crackdown on free blacks, immigrants, and other poor people in the city. That ship already sailed. But he did help establish a precedent that justified the criminalization of free blacks who turned to marginal and informal economies for survival, using the language of morality and ethics to code the racist implications.

African American women were more frequently arrested, received longer sentences for their crimes, and were less likely to be pardoned than other women. Many made a living on the streets working marginal economies as hucksters selling used or slightly damaged or nearly spoiled goods. Others operated or worked in tippling, disorderly, or bawdy houses. Some walked the streets night after night, selling sex or companionship. Still others stole household items from employers or masters such as clothing, items made from precious metals, or even food–facing stiff sentences when caught. Irish and English immigrant women also did all of these things but they were more likely to receive the benefit of the doubt when night watchmen who monitored their comings and goings made split-second decisions about who was simply walking from one place to another versus those deemed idle, disorderly, or vagrant and in need of surveillance. There were great ideological forces already in place that marked white women as least likely to break the law and most deserving of protection by patriarchal authorities. Black women received no such treatment. It was black women—not black men—who quickly outnumbered their white counterparts in the nation’s first penitentiary. This happened largely without remark.

The penitentiary system was still a work in progress in the 1820s. White reformers were increasingly alarmed that young people were held in prison alongside old, hardened offenders. They moved to create a separate institution that would treat these youth like children and offer much needed council and educational opportunities, sparing them the harsh treatment of incarceration. The House of Refuge, opened in 1828, denied admittance to African American children. Roberts Vaux, great Quaker prison reformer, abolitionist, and advocate of public education was intimately involved with the project. By 1829, the House already served fifty-seven boys and twenty-three girls. The reports for the institution do not mention race or an official policy of exclusion, continuing the practice of not talking about race. This exclusion only became evident as abolitionists tried to explain why there were so many black men in prison. It turned out that black boys—denied admittance to the House of Refuge—were added to the total number of black men in prison.

Only in the past decade have the consequences of this practice—the mass incarceration of African Americans—been brought to light on a national stage.

The white elites leading Philadelphia’s prison reform movement rarely said explicitly racist things about African Americans who were incarcerated. This silence signaled a practice of consciously not talking about race in criminal justice, just as officials consciously avoided talk of abolition at the Constitutional Convention and managed to avoid use of the term “slavery” in the final document. Outside observers, however, freely spoke of the racism in the early years of the American justice system. French visitor La Rochefoucault Liancourt declared that whites were granted preferential treatment in the courts and prisons over blacks. He called white reformers hypocrites because they oversaw this discrimination despite belonging to the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. Famous observers Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont claimed there was greater hostility towards African Americans in free states, drawing a direct link between freedom and criminality, “The day when liberty is granted to him, he receives an instrument, which he does not know how to use, and with which he wounds, if not kills himself.” Both European and American elites conceded that the conditions of enslavement nurtured ignorance and dependency but they did little to advance educational opportunities and living wages for free blacks. Rather, they blamed incidents of crime by African Americans as a symptom of their stunted development rather than a result of structural discrimination.

White reformers launched numerous efforts in these formative decades of the young nation, from hospitals and schools to prisons and almshouses. The expansion of the state in the name of democracy, order, and the common public good for all American citizens was fraught from the start. Black women and children seeking to live, work, survive, and thrive were criminalized from the moment they broke free from the chattels of slavery. They were denied the protection and support that white patriarchal authorities offered worthy white women and children. They were punished for seeking freedom—that experience which embodied the very spirit of democracy—and condemned for breaking the law.

The end of slavery did not bring about the promised legal freedom of this country’s underlying principles. Those threatened by freedom necessitated the criminalization of blackness, one that was often made through actions couched in willfully colorblind language. Only in the past decade have the consequences of this practice—the mass incarceration of African Americans—been brought to light on a national stage.

Well-meaning reformers and elites often failed at their stated aims of justice and equality for African Americans because they refused to confront the racist ideologies that informed and justified enslavement. Moving toward an abstract ideal of “freedom” from slavery, prison, mass incarceration without tackling head-on longstanding stereotypes and assumptions about racial difference—chiefly, the criminalization of blackness—will only ever lead to partial inclusions. Understanding of the insidious and profoundly historic role of language—and silence—in justifying the expansion of punishment and the criminalization of an entire class of people is vital if we are ever going to confront this injustice and truly embrace the democratic promise of freedom and justice for all.