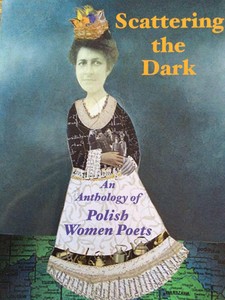

There is no shortage of Polish poetry in English translation—think Miłosz, Szymborska, Herbert, Różewicz, Świrszczyńska, Zagajewski, Lipska, and many others, including younger poets—yet most Anglophone readers, including fellow authors, hardly realize that the poets familiar to them represent but a sliver of varied aesthetic schools and traditions of Polish poetry. While alleged untranslatability of avant-garde or so-called language poets explains some of the omissions, the politics of translation and publishing—a topic for separate essay—is equally to blame for it. What’s more troubling, women poets have been translated much less frequently than their male counterparts. This is somewhat reflected across Polish poetry in general, where women poets are grossly underrepresented in critical overviews as well as in the lists of nominations and winners of the country’s top literary prizes. Called “a passionate, mournful, erotic book of astonished lives” by Valzhyna Mort, and “a useful, subversive, even necessary anthology” by Edward Hirsch, Karen Kovacik’s Scattering the Dark: An Anthology of Polish Women Poets

(full disclosure: I am one of the contributors), published in February by White Pine Press, goes a long way in broadening our perspective of contemporary Polish poetry. This interview was conducted via email.

—Piotr Florczyk for Guernica

Guernica: As you write in your informative introduction, in the recent anthologies of Polish poetry published in the United Kingdom and the United States, work by women poets comprised less than fifteen percent. How do you begin to explain such a blatant disparity?

Karen Kovacik: First of all, the issue of gender imbalance in translation is by no means limited to Poland. According to the Women in Translation website, such a disparity exists for most of the top twenty languages in translation. In 2014, for instance, of 104 books translated from French, twenty-nine were by women. Of sixty-seven translated from Spanish, nineteen were by women. And according to Three Percent, an organization that tracks publishing data in the field of literary translation, most of the top twenty US publishers of translations also revealed an imbalance on their lists in 2014.

That said, in Poland certain factors exacerbate the gender imbalance. Shana Penn in her important book on women in the Solidarity movement and Agnieszka Graff in her books, not least Świat bez kobiet (trans. World Without Women), call attention to historical and cultural factors that contribute to women’s achievements and struggles for gender parity being discounted. During the communist era, in the political opposition, there was a sense that freeing Poland from the yoke of Soviet domination took priority over women’s struggles for equality. Maria Janion, specialist in feminist and gender studies at the Polish Academy of Sciences, for instance, herself espoused such a view, only to be disappointed after the fall of communism. She writes: “It turned out that in a free Poland, a woman is not a human entity but the bedrock of the family, who instead of bothering herself with politics should look after the home” (See Ewa Krakowska’s 2009 article “Feminism Polish Style”). Since the fall of communism, the Catholic Church has been allied with more conservative forces in Polish society, including the Law and Justice Party, currently in power. Such a cultural context can’t help but have an effect on the country’s literature. In literary publishing, reviewing, criticism, and awards in Poland, Kamila Pawluś has noted a significant gender imbalance. In my anthology, I even quote Polish sources expressing regret that Szymborska won the Nobel Prize.

Guernica: In your introduction, you also shed light on “the traditional linking of national identity and poetry” in Poland. This is a fascinating subject, one that’s completely foreign to American poets, many of whom, it seems, wish for poetry to have a larger impact in the US. Have younger Polish poets, both men and women, tried to shed the “Romantic paradigm”?

Karen Kovacik: It’s impossible to generalize absolutely. A poet like Jan Polkowski, for instance, seeks to continue the “Romantic paradigm,” the notion that poetry should serve the nation, in much of his work. In general, though, since the fall of communism there has been less focus on the country’s historical traumas in the work of both male and female poets.

Guernica: Scattering the Dark features the work of thirty-one poets of various generations and aesthetics, translated by you and eighteen other translators. What criteria did you apply to make your selections?

Karen Kovacik: I was guided by numerous criteria. First, as I read book after book of Polish women’s poetry, I began to see that certain themes recurred again and again, which led me to create a thematic structure for the anthology. So one criterion was finding poems that fit each of eight themes. Second, I looked for work that somehow spoke to gendered concerns, though perhaps not every poem fits into this category. Third, I considered literary reputation in Poland, though here, too, while a couple of the poets are less well known I deemed their work important enough to include. Fourth, poems had to work well in English translation. And fifth, I tended to include shorter lyrics.

These chapter headings, by the way, sound like poetry themselves.

Guernica: Instead of the chronological or alphabetical approach, you grouped the poems into eight chapters governed by themes, among them “Lifting the Veils of History” or “A Gallery of Myths and Masks,” introducing each one with a brief essay. These chapter headings, by the way, sound like poetry themselves. Why did you choose these particular themes and not others? Did they become apparent to you while you were making your selections?

Karen Kovacik: I started by reading everything by what Kamila Pawluś calls the “pantheon”: Wisława Szymborska, Julia Hartwig, Anna Świrszczyńska, Urszula Kozioł, Krystyna Miłobędzka, and Ewa Lipska. From reading them I discovered six of my themes: history, Poland’s tradition of bardic nationalism, use of myths, popularity of the ars poetica, the domestic arts, and life transitions. When I broadened my reading to younger poets, I discovered two more: dream poems and curating objects. Surely, there are other categories, and a different anthologist might have called attention to those. But I guess these eight themes reveal a kind of literary conversation across generations of Polish women poets and also implicitly make connections between the included writers and poets beyond Poland’s borders.

Guernica: Some of the poets gathered here, such as Wisława Szymborska or Anna Świrszczyńska, are no strangers to Anglophone readers. Szymborska in particular, whose oft-quoted poem “The End and the Beginning” opens the anthology, has a large following. Some critics might say that her spot should have been given to a hitherto unknown poet.

Karen Kovacik: One of my readers prior to publication suggested I not publish thirteen poems by Szymborska in the anthology. But, in the end, I didn’t take her advice because I thought it important for Anglophone readers to read the Polish Nobel Laureate in the company of other prominent and emerging women poets from her country. It is also important to show that Szymborska was not immune from sexist treatment. In the History of Polish Literature, Miłosz even referred to her as “a poet who leans toward preciosity…[who is] at her best when her women’s sensibility outweighs her existential brand of rationalism.”

This apocalyptic landscape both enthralls and depresses the speaker, perhaps not unlike Poland itself, with all the changes and upheavals brought about by the country’s transition from communism to democracy.

Guernica: There is a lot to admire in Scattering the Dark. The work by Joanna Lech (b. 1984), with its cascading offhandedness, seems particularly rich. In “Postscript” she channels an inability to grasp, literarily and figuratively, her surroundings: “Back behind the train station lie ruins of houses, shattered windows, trash. A broken swing. / Nothing’s here, nothing’s left, the tracks are overgrown. So I don’t understand / what you’re doing, twirling around, holding out your hands.” This apocalyptic landscape both enthralls and depresses the speaker, perhaps not unlike Poland itself, with all the changes and upheavals brought about by the country’s transition from communism to democracy.

Karen Kovacik: Thanks for that sensitive reading. That’s precisely how I see Lech’s poem.

Guernica: Likewise, Agnieszka Mirahina (b. 1985) seems drawn to the quotidian reality, with its incessant flow of political and marketing bombast, if only because it reminds her of the past. Here are a few lines from “All the Radio Stations of the Soviet Union”: “and no one really knows who purged the truth from that fairy tale / since the ants had always been here had remained in Asia this is Moscow calling // each word’s an order in the grammar of crackles hisses static / all radio stations of the Soviet Union are working.” Ironically, by employing a radio metaphor, Mirahina announces her desire to be heard loud and clear. Does she succeed?

Karen Kovacik: I think so! I found it interesting that Mirahina, only four years old when the first free elections were held in postwar Poland, used this punny, neo-Language idiom for taking on the Soviet Union, the Katyń massacre, and the end of the Warsaw Uprising.

Guernica: The slightly older Justyna Bargielska (b. 1977) is another poet who’s been well received in Poland. You point out that all her poetry volumes have English-language titles. Elsewhere you in your introduction, you make the case for seeing these poets for what they are: “a cosmopolitan group, influenced by extensive contacts with other literatures and languages.” It’s true that Poland and Poles are generally worldlier and more open-minded than ever before, but what do you make of Bargielska’s decision to title her books in English?

Karen Kovacik: I’d like to take your larger point first. Writers from relatively small countries (or language groups) must cultivate relationships with writers, translators, and readers of other countries. In this regard, Poles are no exception. And that multilingualism is something that writers and readers on the American scene don’t always understand or appreciate. Since the fall of communism in 1989 and again after Poland joined the European Union in 2004, opportunities for freer travel and cultural exchange have grown tremendously. And the poets in my anthology—as professors, writers, editors, and translators—have all contributed to the notion of “words without borders,” to a literature that’s both homegrown and outward looking

As for Bargielska, not all of her books do have English-language titles, but many do: Dating Sessions, China Shipping, Bach for My Baby. Perhaps there are Polish nationalists who would accuse her of selling out or giving in to globalization, but I see her aiming for a resonance that will draw in readers beyond Poland’s borders and loving certain sounds and rhythms from English that can reverberate in interesting ways with her poems in Polish.

Guernica: Another striking component of this anthology is how short many of these poems are. Most American poets prefer long, sprawling narratives that often rework the classics or incorporate historical facts and documents freely. At least some of it stems from the poets’ desire to reach a larger audience by dismantling the division between poetry and prose. Would you say that Polish poets have more faith in lyric poems to get across to their readers? Here’s Krystyna Miłobędzka’s untitled poem in its entirety: “strip yourself of Krystyna / of child mother woman / lodger lover tourist wife / what’s left is undressing / trails of discarded clothes / light gestures nothing more.” As an award-winning poet and creative writing professor, you must come across all sorts of poets in your reading life and in the classroom. What would you say are some of the other formal and thematic differences and similarities between American and Polish women poets?

Karen Kovacik: Well, that’s a large question! In some ways, as I mentioned earlier, I deliberately skewed the sample by including a preponderance of shorter poems. Yet I suppose in Poland there are more short poems, maybe because of certain minimalist traditions in poets such as Tadeusz Różewicz or Anna Kamieńska, which privilege the fragment, the attenuated, the dwindling number of words that can still earn our trust. A related observation is that poets often feel comfortable leaving poems untitled, trusting somehow that the reader will find something of value even with the frame left off. The brevity of poems and omission of titles might be due to Poland not having the creative writing establishment that the US does. This is another huge generalization, but I believe more Anglophone women poets write more explicitly about the body, though of course there are exceptions on either side of the equation.

Guernica: Your publisher, Buffalo’s White Pine Press, has long been a supporter of poetry in translation. How did you approach them about publishing Scattering the Dark?

Karen Kovacik: Dennis Maloney of White Pine had already issued my translation of Agnieszka Kuciak’s Distant Lands: An Anthology of Poets Who Don’t Exist. Another publisher said he would only be interested in the project if I created a mixed-gender Polish anthology. At an Associated Writing Programs conference a few years ago, I mentioned this to Dennis, and he burst out laughing. Then he said he would be interested in taking on an anthology of Polish women poets.

Guernica: The publication of most translated books is partially financed by the author’s home country, in the form of a translation grant or similar government subsidy. What are the pluses and minuses of such an arrangement?

Karen Kovacik: I’ve grateful to the Instytut Książki (trans. The Book Institute) for its support of Polish literature in translation. Without its funding, Polish poetry would not have achieved such prominence on the world stage. But often translators and authors make very little for a translated work.

…I sometimes feel I’m part of a decades-old conversation skipping back and forth across the big pond.

Guernica: Do you think Scattering the Dark will alter our understating of Polish poetry?

Karen Kovacik: I hope so! More than anything, I hope more individual volumes by Poland’s women poets grow out of this collection.

Guernica: Finally, you are both a poet and translator. Can you talk about how these two activities coexist in your writing life?

Karen Kovacik: I find that I go through some periods where I focus on my own work (I’m in one now) and ones where I concentrate on translation. From my close reading of contemporary Polish poetry, I find new rhetorics or means of discovering poems of my own. For instance, Julia Fiedorczuk, a poet in the anthology wonderfully translated by Bill Johnston, has taught me so much about ecopoetics, and I love her fresh, surprising images, her reinventions of ordinary Polish phrases. Agnieszka Kuciak showed me how to do a “big concept” book like her faux anthology of twenty-one invented poets. Jacek Dehnel has such a voracious mind: astronomy, botany, chemistry, painting, biology, music—it all shows up in his poems. And as a literary translator, he often borrows forms from some of the poets he translates—Philip Larkin, W.H. Auden, Carl Sandburg—so I sometimes feel I’m part of a decades-old conversation skipping back and forth across the big pond.