By Kate Webb

The reasons that so many twentieth-century writers, everyone from Vladimir Nabokov to Angela Carter, turned to film as a metaphor for modernity were manifold, but part of the attraction was the internationalist milieu in which Hollywood evolved, one that helped the city become an important focus for radical idealism and then for the reaction against it. In the Silent era, skills were translatable: neither mother tongue nor accent were of concern when it came to joining a film’s cast or crew. So as Hollywood’s success and purchasing power grew, actors and directors were fetched from across the globe and by the early ’20s, Hollywood was cosmopolitan enough to have earned the name “Hollywood Babylon.”

Whether this meant heaven or hell depended on your idea of paradise. For some the title referred to the city’s large expatriate community, to others it implied the debauchery D.W. Griffith depicted in Intolerance, his 1916 film about the fall of Babylon. The two visions, of course, were not mutually exclusive; together they helped to define Hollywood not just socially but politically.

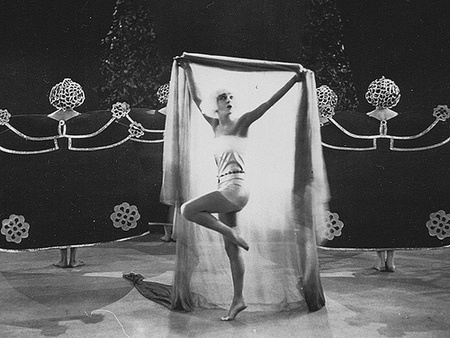

Alla Nazimova, the actress Adolph Zukor once called “the quintessential Queen of the Movie Whores,” was typical of this milieu, her exoticism provoking adoration and horror in equal measure. In 1918, she bought a mansion and plot of land on Sunset Boulevard, then still only a dirt road. Here she established one of Hollywood’s earliest salons where you were as likely to find Charlie Chaplin or Valentino as Nazimova’s women friends and lovers (these included ex-wives of both men). They all liked to role play: “My friends call me Peter and sometimes Mimi,” Nazimova told one columnist.

Born Miriam Edez Adelaida Leventon, Nazimova was Crimean and Jewish. In Russia she had been friends with Chekhov and Gorky, and studied under Stanislavksi (paying for lessons, her biographer Gavin Lambert suggests, by working as a part-time prostitute). She arrived in New York in 1905, coming from St. Petersburg by way of Berlin and London, where she was a member of Pavel Orlenev’s avant-garde theatre troupe. It took just one year for her to become a sensation on Broadway even though she knew only a handful of English words.

When Pavel returned to Russia, her career in theatre began to wane. So she made her bid for celluloid, its immortality seeming more commensurate with her ambition. For her first outing, War Brides, shot in New York in 1916, she was paid $1000. The following year, David O. Selznick’s father, Lewis, helped her to complete her migration westward, taking her to Hollywood, where she put her ambition to work, producing, directing, and writing many of the films she starred in. With proceeds in hand (she was soon earning $13,000 a week) the “Woman of a Thousand Moods,” “the greatest artist of the screen,” as Metro Pictures presented her to the public, took possession of her mansion.

Nazimova was not an obvious choice for Hollywood: on her arrival, studio bosses were appalled by her moustache, insisting she shave it off despite Nazimova’s claims that in Europe it was considered attractive.

Set in three and a half acres of tropical vegetation, The Garden of Alla, as Nazimova knowingly named her estate, was garlanded with exotic birds: the feathery kind could be found in an aviary Nazimova installed; the two-legged creatures, like Chaplin’s wife Mildred Harris or Valentino’s two wives—the actress, Jean Acker, and the costume designer, Natacha Rambova—paraded on the terrace overlooking the vineyards. Nazimova lived here with fellow actor Charles Bryant, her pseudo-husband, who was reputedly paid 10 percent of her salary for acting the part. Although the two flirted in public they did not share a bed. This privilege Nazimova reserved for a succession of female lovers, many of them part of the lesbian and bisexual coterie known by those in the know as “the sewing circle.”

She was not an obvious choice for Hollywood: on her arrival, studio bosses were appalled by her moustache, insisting she shave it off despite Nazimova’s claims that in Europe it was considered attractive. And her ideas were too literary, too highbrow: “I wanted to do thoughtful things, things subtle and only hinted at,” she told Djuna Barnes in 1930. Trying to achieve this she spent her earnings on expensive, “artistic” productions of A Doll’s House and Salomé. But these were too advanced for America’s homespun taste and they flopped. Sensing that her money and luck were about to run out, Nazimova built twenty-five apartments on her estate and began renting.

In 1927, The Garden opened to the public, setting the standard with a star-studded shindig that lasted through the night and long into the next day. Only a year later, though, the Russian actress’s grand scheme had financially ruined her and she was forced to sell. Wanting to strip the place of its association with its former hostess, the new owners added an ‘H’ to Alla, leaving a name that some could barely credit: “I’ll be damned” Thomas Wolfe wrote to Scott Fitzgerald in 1939 on discovering his friend’s new address, “if I’ll believe anyone lives in a place called ‘The Garden of Allah.’” Tallulah Bankhead thought it “the most gruesomely named hotel in the western hemisphere.” The Wall Street Crash, meanwhile, took what was left of Nazimova’s fortune. Characteristically she rallied, though, and with her final lover, the actress Glesca Marshall, returned to take up residency in The Garden once again, living there until her death in 1945.

Whether or not she owned The Garden, Nazimova’s example meant that the place was home to many glamorous, brilliant, expatriate, and by American standards, unorthodox inhabitants. Pola Negri, Greta Nissen and Marlene Dietrich stayed there. The Swedish sphinx Greta Garbo particularly loved the pool, then the largest in Hollywood, and she used her rooms during a brief liaison with John Gilbert—before returning to the company of women and gay men, whom she usually preferred. The German director, Ernst Lubitsch had an apartment as did the Italian actor Roman Navarro, while the Australian Errol Flynn conducted affairs at The Garden with the Mexican actress Lupe Vélez and the French actress Lili Damita. Cary Grant wanted to stay when he first arrived in town, but unlike other English residents such as Charles Laughton and Laurence Olivier, he couldn’t afford to.

There were of course also home-grown inhabitants who were broad-minded enough to enjoy the continental clientele and partake of the freely available drink and drugs. (At The Garden, it was said, Prohibition acted more like a stimulant than an embargo.) Buster Keaton, the Gish sisters, Gloria Swanson, Fairbanks and Pickford, W.C. Fields, Edward G. Robinson, Bogart and Bacall, Orson Welles, Grace Kelly, and Frank Sinatra all stayed at one time or another.

In 1927, Hollywood started to talk: “You ain’t heard nothin’ yet!” was the famous opening line—an example of the kind of wit that would enliven its best scripts—and producers began recruiting writers in earnest. Many of them would pull up at The Garden. Besides Fitzgerald who wrote the Pat Hobby stories there, guests and visitors to the bungalows and apartments included his friend, Dorothy Parker and many of the Algonquin set she drew on her coattails; also, at one time or another, P. G. Wodehouse, Raymond Chandler, Hammett and Hellman, Ernest Hemingway, William Faulkner, Clifford Odets and André Malraux.

Photographs of female stars wearing trousers or in athletic poses, or of male stars like Cary Grant and Ronald Coleman in their pyjamas breakfasting together, suggested, to those who were paying attention, that there was more than one way to live.

Then there were The Garden’s impressive array of musicians: Rachmaninov, Stravinsky (who was Harpo Marx’s neighbor, and whose “overpowering” piano playing disturbed the comedian’s harp practice), Toscanini, Mischa Ellman, and Jascha Heifetz, as well as the jazz musicians Woody Herman, Benny Goodman, Cole Porter, and Artie Shaw together with his wife of the time, Ava Gardner. There was the ballerina Anna Pavlova, the boxers Joe E. Louis and Jack Dempsey, and perhaps most surprising of all, one of Nazimova’s early guests was rumored to be Albert Einstein, visiting America in 1921 after winning the Nobel Prize. By any standards it’s an astonishing cast and it’s hard to imagine such a congregation again. Today it would be impossible to accommodate the egos or the entourages. In its heyday, though, The Garden became synonymous with Hollywood, a distillation of all of the pleasure and all of the anxiety that movies provoked.

The casual mixing of people from across the world at The Garden broke down many barriers. Its rich, beautiful, smart, and successful people were confident enough to exercise the kind of sexual freedom that would land you in jail elsewhere in the country. Admittedly, much of this behavior was closeted, but the message still got out. Photographs of female stars wearing trousers or in athletic poses, or of male stars like Cary Grant and Ronald Coleman in their pyjamas breakfasting together, suggested, to those who were paying attention, that there was more than one way to live, one way to be. All this was central to the allure of Hollywood. Nazimova may have been forced to shave off her “clearly defined moustache,” but ambiguity was a part of the city’s seductive mystery—whether it was Grant flouncing around in a woman’s dressing gown in Bringing Up Baby, shouting, “I just went gay all of a sudden!”; Katherine Hepburn or Louise Brooks, crop-haired and disguised as boys; or Dietrich and Garbo dressed in men’s clothes and romancing women.

Even when the new owners took over, the presiding spirit remained Alla’s—freethinking and acting, secular and satirical. Fitzgerald’s last love, the columnist Sheilah Graham, whom he met at a party at The Garden in Robert Benchley’s bungalow, thought the main tenor of the place was that whatever you did there, “no one paid any mind.” In her book memorializing The Garden, she shows how such insouciance was a matter of deportment and tact, the visible sign of how free people might live together: for many it did not therefore preclude political commitment.

Indeed, by the ’30s, Hollywood’s heady mix of cosmopolitanism, radicalism, and remarkable payslips produced a unique atmosphere: “Dialectical materialism by the pool,” the screenwriter Budd Schulberg, friend of Fitzgerald and a Communist Party member, called it, remembering the radical chatter he continually heard in the mansions of the rich. The Garden specialized in this kind of talk: it was here that Dorothy Parker, Charles Brackett, and Donald Ogden Stewart got wildly drunk together and plotted the Screen Writers Guild; here, too, that Frederic March gathered its residents to watch a screening of The Spanish Earth, the anti-Franco documentary written by Hemingway and Dos Passos about the civil war, and solicited $1,000 towards the cost of ambulances in Spain from each of the guests—though Errol Flynn, Graham reports, ran off without paying.

Parker, a communist and founder of the Anti-Nazi League, conducted a variety of political activities at the Garden’s poolside, where she and her husband Alan Campbell lived for a while. And even after the two moved into a palatial Beverly Hills home, dressed with Picassos, from where they hosted highly successful fund-raising events raising millions for the anti-fascist cause, Parker continued to haunt The Garden, calling out a reluctant Fitzgerald, the friend she’d once been sweet on, to come with her to political meetings. Eventually some of this talk found its way into The Love of the Last Tycoon, the novel about “the whole equation of pictures” in Hollywood that Fitzgerald had begun working on, charting the relationship between moguls, players, unions, and workers. (“You don’t really think you’re going to overthrow the government.” “No, Mr. Stahr. But we think perhaps you are.”)

The philosophy the radicals were pursuing was European in origin, but their tone was pure American, reflecting what the Australian novelist Christina Stead wrote of the American mindset when she first visited the U.S. in the Thirties: “I thought the whole country twanged with impertinence.” The modernity and freedom articulated in such insolence is part of what drew Nazimova and many of the early twentieth century émigrés to America, together with a chance of greater money and fame than they could earn at home. But others who came were exiles from history: Jews denied the chance to prosper, escapees from the Russian revolution. With the advent of sound this extraordinary creative and business community might have thinned out and yielded to assimilation, but the onset of fascism in Europe produced a new crop of refugees in search of a home.

Hollywood, with its large international community, was an obvious choice for artistic and political dissidents. And they came, among them Fritz Lang, Robert Siodmak, Max Ophüls, Hans Detlef Sierck, who like many émigrés changed his name in Hollywood, to Douglas Sirk, and Bertolt Brecht—a good friend of the Ukrainian actress and screenwriter Salka Viertel, who was another of The Garden’s habitués and another of Garbo’s lovers. She and her husband Berthold Viertel (immortalized in Christopher Isherwood’s 1945 novel about filmmaking, Prater Violet) had planned to return to Vienna, but stayed in America, fearing the darkness descending over Europe.

“The Hollywood Communist Party was like Sunset Strip. Thousands of people used to go there, hang around a little while, and then pass on some place else.”

Viertel ran her own salon attended by many of the brilliant and distinguished newcomers: the Mann brothers, Arnold Schoenberg, Max Reinhardt, Kurt Weill, Hanns Eisler, Lion Feuchtwanger, Alfred Döblin—who was allowed into America in 1940 with a contract to write for MGM at $100 a week—and Brecht, who arrived from Finland in 1942 and began working for United Artists with Eisler and Fritz Lang on the anti-Nazi film, Hangmen Also Die! A good number of them were communists and aligned with them in a loose coalition were Hollywood’s old New Deal progressives and supporters of the Republican cause in Spain, who found themselves attracted to the lively social life organised by the Party. The writer and director Abraham Polonsky said that at this time, “The Hollywood Communist Party was like Sunset Strip. Thousands of people used to go there, hang around a little while, and then pass on some place else.”

For these communists, New Dealers, and fellow travelers living amid the opulence of Hollywood, giving away a percentage of one’s salary to the Party or to the fight in Spain was not always enough to ease the contradictions between fantastic personal wealth and egalitarian beliefs. “I was the only person to buy a yacht and join the Communist Party in the same week,” said the actor Sterling Hayden, self-mockingly. But he was not alone: guilt about earning vast amounts of money, first in the middle of a Depression, and then as fascism advanced in Europe, had been a motivating factor for becoming active in left wing politics. For many in Hollywood, though, the point was not to redistribute down, but to level up. Communist idealism meant an end to deprivation, and after the revolution there would be bouquets and banquets for all; like Nazimova, everyone would be free to imagine and create their own paradise, to share in the bounty of the garden.

In his 1975 autobiography, By a Stroke of Luck, the screenwriter Ogden Stewart, another friend of Fitzgerald’s and President of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League, describes this optimistic belief in the redistribution of wealth and fun, in which, rather than dismantling palaces, their doors would be opened to all: “Let it be understood…that the romantic ‘communist’ did not beat his Hawes and Curtis stiff dress shirt into a hairy one and set out with begging bowl to Do Good. I wanted to do something about the problem of seeing to it that a great many people were allowed into the amusement park. My new-found philosophy was an affirmation of the good life, not a rejection of it…”

Christina Stead, who worked at MGM in 1940, captures this mood brilliantly in I’m Dying Laughing, her novel about left wing writers in Hollywood, which goes some way to explaining how those who instinctively loathed the discipline of “collective responsibility” or the crudeness of the Party’s line on culture—how even writers like Fitzgerald—kept company with communists and were periodically caught in the net of their enthusiasm. And for a while, in the Hollywood gardens at least, this romantic communism could be sustained. But in I’m Dying Laughing, what begins in California as an attraction to the ideal of plenitude over scarcity is stretched to the limits of credibility when Stead’s protagonists, now exiled from America by the anti-communist blacklist and living in the lap of luxury in postwar France, sing out their battle-cries—“crêpe flamandes for the masses!… Pressed ducks for the people”—while those around them starve on rations and rotten bread.

It’s an outcome that suggests Hollywood’s romanticism was always self-deceiving: the idealistic belief that the world could be a more sumptuous place in which everyone could be equally generous and prodigal is revealed, flagrantly (and perfectly in tune with the postwar mood), as the mask of bad faith. Even before the war, however, the sense of hope and the self-ironizing American sensibility that had proved so winning in a string of Thirties movies (so liberating and expressive of a democracy in full flight) was starting to sour. By 1939, and the Hitler-Stalin pact, the contradictions of such a life were proving for many too great to endure. At one point in I’m Dying Laughing, Emily, the central character based on Nathanael West’s sister-in-law, Ruth McKenney, derides herself for betraying her talent by screenwriting for money rather than working on something literary, serious, and “authentic,” all while at the same time, against her better impulses, continuing to toe the Party line: “Jehesus-Jehosaphat! I’m always doing the opposite of what I want. It’s dialectical I guess. The latest word for selling-out.”

This only foreshadows the greater treachery to come: Stead’s protagonists end their dream of being on the side of the angels in history by naming the names of their erstwhile comrades, giving them up to the investigating committees just as Schulberg, Garfield, Hayden, and countless others were to do in real life. The rapid descent from radical idealism to McCarthyite backlash was perhaps more keenly felt in Hollywood than anywhere else in America. From 1947, when the first House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings on the film industry took place, to the breaking of the blacklist by Otto Preminger and Kirk Douglas in 1960, a decade of revelations, betrayals, false names, and regretted lives reached all the way to the higher echelons of the industry where those who dared initially to demonstrate against the trials found themselves locked in hotel rooms signing “confessions” for FBI agents and shadowy right-wing business organizations such as the League of America.

Inevitably Nazimova’s Garden succumbed to the dreariness of modern times—paradise was paved and a McDonalds and a bank put in its place.

The political power of these forces was so great that even movie heroes, men like Humphrey Bogart and Gene Kelly, could not escape their grasp. In the end, after demonstrating in support of the Hollywood Ten (the group of writers and directors sent to jail for refusing to cooperate with the committee), Bogart hung his head and requested a closed hearing of the HUAC in which he declared he had never been a communist. Kelly, as powerful as he was, could not save the career of his wife, the actress Betsy Blair, a communist, but never a Party member: she was blacklisted, and the fall-out from this contributed to the destruction of their marriage, as it did for many couples in the industry.

The Garden, of course, had always had its snakes, right wing residents like Ginger Rogers and her rabidly anti-communist mother, Lela, who took up residence in 1932, as well as the ultimate snake waiting to slough off his skin and usher in the new Cold War politics, the FBI informant known as T-10: Ronald Reagan. (Incredibly enough, Nazimova was Nancy Reagan’s godmother). By the Fifties many of the HUAC’s victims had been thrown in jail or out of the country: Brecht testified (but in an evasive and equivocal manner) then fled to Switzerland; from The Garden, Parker, Hellman, Hammett, Ogden Stewart, Viertel, Welles, Edward G. Robinson, and Artie Shaw were all blacklisted, along with hundreds of others in Hollywood.

The paranoia and loss of faith this resulted in was reflected in The Garden, now a more menacing place: drinking descended into brawling and the occupants were as likely to be police or con men as actors or writers. Its nadir came one night when thieves broke in and shot the night watchman. Many felt the final party held before The Garden closed in 1959, where guests came dressed as early film stars, was proof that the dream was over: a diminishing self-parody that mocked its earlier brilliant spirit of originality.

Inevitably Nazimova’s Garden succumbed to the dreariness of modern times—paradise was paved and a McDonalds and a bank put in its place. But it persisted in the imagination, at least, as a place of freedom and tolerance. In 1946, a gay cabaret club opened in a Seattle basement with the same name. A regular visitor there remembered this new Garden as heaven on earth: “In it we found love, understanding, companionship, friendship, and a common bond. We were more or less one big family.” The rare combination of conviviality and creativity that Nazimova fostered in her wild Garden, made it, as Harpo Marx once said, “a pretty mad place.” For the same reason, Artie Shaw remembered just how conducive the devil-may-care attitude of The Garden was to self-liberation: “It was always a little shabby and run-down. You’d expect the rats to come. No one was polishing the tops of the palm trees. The Garden was one of the few places so absurd that people could be themselves.”

Kate Webb’s essays on Christina Stead and Angela Carter have been published by Virago, Macmillan, and the Halstead Press. She is writing a book on the dream life of Eleanor Marx.