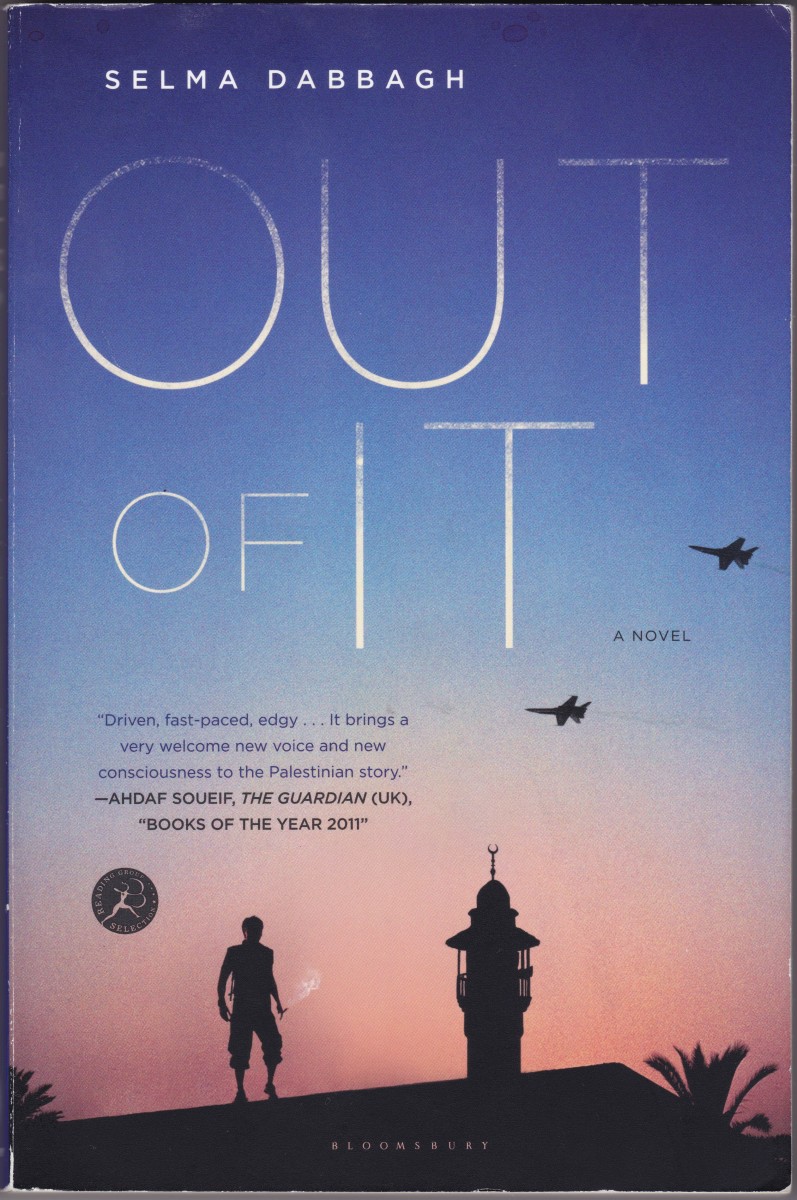

—Excerpt from the novel Out Of It

Out Of It begins with a nighttime aerial bombardment and its bloody morning aftermath for a family in Gaza. The three adult siblings of the Mujahed family, Rashid, Iman and Sabri, live with their mother Jihan in what used to be a block of eight identical buildings; now surrounded by tent-dwelling neighbours, theirs is the last residence standing. Rashid, 27, having spent the night of the bombing getting defiantly stoned, wakes to the news that he’s been awarded a full scholarship to graduate school in London. Iman, his twin sister, has been working in Gaza for a year as a teacher since completing her education in Europe. When the bombing begins, Iman is trapped at a meeting with several other women. The next day she learns that one of her students, a little girl, was killed when the hospital was bombed during the night. Like Rashid, Iman struggles to stay above despair and maintain a sense of purpose and belonging in Gaza.

I first encountered Dabbagh’s writing through the streetwise voice, spiked with humor and innocence, of the teenage Jewish Londoner who narrates her 2007 short story “Down the Market,” an electrifying account of Israeli settler violence in the West Bank. Dabbagh creates characters who face extreme situations—bombings, interrogations, the violent deaths of family members and friends, the deaths of children. I’ve been struck, both in her short stories and in Out Of It, by the kind of mental dexterity her characters need to survive, switching from the flight-or-fight response to the fierce persistence of the private individual in maintaining a continuous self. They have specific, irreducible memories and emotional attachments—her character Sabri keeps a shirt that had belonged to his wife Lana wrapped in plastic, believing it still has her scent, for example—and the capacity for tenderness and humor and regret and hope for future happiness. They are as susceptible to having their hearts beat faster at the sight of a certain man or woman as any Austenian maiden at a garden party.

—Rahat Kurd for Guernica

Guernica: Is it possible to say whether the personal precedes the political for you? In your work, the two have a way of coming at the reader so intensely at once that I wonder if you regard this as your central creative task. This quality in her work reminds me of the South African novels of Nadine Gordimer, for whose characters surviving and resisting the dehumanizing impacts of apartheid comes to us through their private emotional lives.

Selma Dabbagh: My primary focus is the personal. The personal and political were so tightly entwined in Out of It, as the pressure to be politically engaged was one of its key themes. My later work may veer away before it veers back to such a politicized terrain. In terms of my central creative task, I would say that that is to be true to myself. I am a great admirer of Gordimer’s work, particularly her short stories. She had an extraordinary knack for catching the finest calibrations of human emotion. I was probably more led by writers like Gordimer in terms of where I wanted to place myself on the political-personal spectrum than other Palestinian writers. I got to the point in the writing process where I decided to jettison the idea of conveying the whole of Palestinian history (I started out with the idea of writing a grand epic or saga starting in the 1930s) or even any particular message. I just wanted the characters to live and breathe on the page, for their emotions and desires to be communicated to the reader. The fate of a character where there is no history, no connection, no belief, will not stay with you longer than a headline statistic. But, having said that, you cannot write the personal without having a good understanding of the big-picture political issues that influence your characters’ lives. As the surrealist painter and writer Leonora Carrington put it, “to possess the telescope without the other essential part, the microscope seems to be a symbol of darkest incomprehension. The task of the right eye is to peer into the telescope while the left eye peers into the microscope.”

If you grow up in a society where you are predominantly defined by your sexual status and outlook, you become painfully aware of it.

Guernica: I’d like to talk about your portrayal of Iman, the young female protagonist. At one point in the novel Iman admits to herself that she’s attracted to a political activist she met in Gaza. Despite her own strong capacity for leadership under extremely harsh circumstances, Iman feels ill-equipped for intimate relationships, inhibited by what she feels is lack of experience. The contrast will be very familiar to many readers who are raised with both a lively social justice consciousness and traditional Muslim family and community expectations.

Selma Dabbagh: Iman was a tough character to write. I kept feeling that she disapproved of and disliked me, that to her, I was a “sellout” like her father. I started writing the novel when I lived in Bahrain and was effectively a corporate housewife in my 30s. I had been a lot more politically active previously and the shift to an enforced depoliticized setup sat uncomfortably with me. In the early drafts Iman came through as too harsh and unlikeable. There was no nuance to her. She was like a reprimanding conscience haranguing me. If you grow up in a society where you are predominantly defined by your sexual status and outlook, you become painfully aware of it.

Guernica: And yet, she is determined to have a private life on her own terms. When she eventually makes it to London, we see Iman very deliberately initiate the seduction of a man she meets at a party, as if it’s something she is determined to go through and get over with. It’s very funny. But later on, she finds a powerful emotional connection with someone else, someone also from Gaza.

Selma Dabbagh: Exploring Iman’s sexuality gave her the vulnerability and depth she needed. In her case the seduction was definitely a rebellious act, but it left her feeling nothing in particular.

Personally, I’m with the Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani, who said that political liberation is not achievable without sexual liberation.

Guernica: I wonder if it takes female characters like Iman to create more awareness and sensitivity around women’s sexual autonomy. Have you had any memorable reactions to her?

Selma Dabbagh: An older Communist male friend of mine was concerned about the perception of Iman in terms of her sexuality—and that moral judgment of her really put me off. I suppose how we choose to portray a character is a bit more instinctively Victorian—that if it doesn’t result in a marriage it shouldn’t be represented at all. But I can think of many writers from the Arab world whose treatment of women’s sexuality is much more rebellious than mine; Randa Jarrar’s robust A Map of Home (set between Kuwait, Egypt, Palestine and the US), and Hanan El Shaykh’s The Story of Zahra which deals with sexual abuse and incest in a lower income Beiruti family. Ahdaf Soueif’s In the Eye of the Sun (set between England and Egypt), writes more poignantly about the difficulties men have with women asserting their sexual desire than in any other novel I have read. When I was in my late teens, early twenties, I was just exhilarated to find this book, written by this woman who had this funny Arab name, that this could be a subject of fiction—it was really revolutionary—it made me look at my whole experience in a new light—it gave me a vocabulary for understanding the whole context of where I’d lived in the Gulf. The intricacies and complexities of a marriage that looks like it should fit and it just doesn’t. It helps you to legitimize your own thoughts and actions and to think of other potential remedies to your own situation.

Writers from Arab, Muslim, South Asian and other backgrounds are opening up many avenues for women in terms of how they view their own sexuality. Some groundbreaking writing is going on. It is an old gripe, but still a pertinent one, that women’s liberation whether sexual or otherwise is placed at the end of the list of priorities when it comes to any kind of struggle for national liberation or representation. Personally, I’m with the Syrian poet Nizar Qabbani (among others), who said that political liberation is not achievable without sexual liberation. Clamping down on women’s sexuality shows nothing more than a desperate loss of power on the personal and political fronts, a meanness of spirit, and a lack of ideas about what to do next.

Guernica: Where in the world have you travelled with Out of It?

Selma Dabbagh: All over the place. From several towns in England, to Malta, Dublin, Beirut, Qatar, Bahrain, Jaipur, New York, Lahore, Ramallah, Gaza, Edinburgh, and Glasgow.

Guernica: Tell me about the conversations you’ve had with your audiences.

Selma Dabbagh: Audiences have been so varied, from knowing nothing at all about Palestine to being academics and students of the region and its literature. Each event has its own challenges. I have been heckled and harassed by Israelis, but not as much as I thought I would be. Although this is a relief on a personal level, it also worries me. It seems Israel’s national psyche is being encouraged to be so sociopathic and lacking in empathy that no one comes out to challenge you. It used to be that there was a denial that Palestinians existed, then a denial that Palestinians suffered, now it is as though they are saying, we know you suffer, but who cares? Audiences are normally quite respectful even if they don’t agree with where I may come from. Many in the UK in particular are outraged by the situation in Palestine and there is a feeling of historic responsibility, a continuing guilt and a national debt that needs to be repaid (particularly with the older members of the audience). The younger audiences I found the most exciting were in Gaza and in Lahore. In Gaza, I was struck by the girls in particular, how intrinsically anti-authoritarian many of them were, how well read, how undaunted by speaking their minds. In Pakistan, it was really gratifying to see how themes in my novel were picked up on and understood by readers; there was a class of people who felt alienated both by their own pro-Western government as well as by the growing Islamic extremism—a parallel with the difficult middle ground that my characters were trying to tread.

Guernica: Tell me about the Palestinian Festival of Literature (PalFest). Does literature or literary engagement change the conversation around Palestine, whether it is young Palestinians envisioning their future, or with your own experience as a Palestinian-British writer in London?

They responded to the idea that writing is for the opening up of space to express yourself—not to feel that you have to postpone making space for art and beauty until the political struggle is over.

Selma Dabbagh: PalFest allows international writers to experience Palestinian society under occupation first-hand. It is globally unique in being a travelling literature festival. As the audiences can’t travel, the writers do. They go through the checkpoints of Jerusalem to Ramallah, Hebron, Jenin, and Nablus in the West Bank. Writers have been harassed and stopped. Venues have been closed down and audiences tear gassed by the Israeli authorities. At PalFest in Gaza in 2012, a poetry reading I attended for the final concert was closed down by armed men said to be Hamas by everyone other than Hamas. Writers, publishers and journalists see the reality of life under occupation and siege and write about it. That is one function of the Festival. It also made the publication and reception of my novel slightly easier, as my editor, Alexandra Pringle, editor-in-chief at Bloomsbury, had attended PalFest twice. She describes it as being a life-changing experience and has published many Palestinian writers, and books about Palestine, since. Many of the journalists and individuals who supported and promoted Out of It and other literature on Palestine were better able to understand the work in context, as they had also had experienced the extremity of current realities by attending PalFest. It is therefore easier for books about Palestine to get published since PalFest, as there is greater understanding of that world in the mainstream media. Whether that is due to social media or literature or the legacy of Edward Said is hard to gauge, but there are definitely more well established intellectuals with first hand experience of Palestine since PalFest than there were before it.

The other side of the Festival is what it brings to Palestinian society in terms of literature. It not only enables Palestinians working in the arts, writing and studying literature, to meet writers they would never previously have met, but provides them with creative writing classes where they can express ideas; there is a liberation to opening up the imagination which needs to always remain the freest space of all. I noticed that some of the girls who came to creative writing class would at first think that of course they have to write about Palestine and the refugee experience. And their bodies would kind of sink. But they really responded to this idea that writing is for the opening up of space to express yourself—not to feel that you have to postpone making space for art and beauty until the political struggle is over.

Most of the PalFest events are also fun. I do not say this frivolously. There is a real need for outlets for enjoyment in Palestinian society. We need a sense of celebration of who Palestinians are and what we could be, if given the space to do so. At one event that I attended in Gaza, a music concert, there were 19-year-olds who had never attended a concert before in their lives. It was extraordinary to experience. I felt like the room would burst before the event even started.

Selma Dabbagh is a British Palestinian writer of fiction. Her short stories have been published in Granta, Wasafiri, International PEN, Telegram Press and other publications. Some of these stories have won or been nominated for prizes. Her first novel, Out of It (Bloomsbury, 2012) set between Gaza, London and the Gulf, was nominated as a Guardian Book of the Year in 2011 and 2012 and was critically acclaimed across the political spectrum from the Financial Times, the Economist and the Daily Telegraph to the communist Morning Star in the UK. Her first play, The Brick, was produced by BBC Radio 4 in January 2014 and nominated for an Imison Award. She is finalizing her second novel, We Are Here Now and thinking about her third. Selma lives in London.