“I would to God Shakespeare had lived later, & promenaded in Broadway.”

—Herman Melville, Letter to Evert A. Duyckinck Mar. 3, 1839

“Is Shakespeare Dead?” wondered Mark Twain in 1909, and we are still debating it today. Does Shakespeare matter? Or is his work elitist gobbledygook we are forced to swallow like oily medicine? 2016 marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and this column will spend the year exploring the ways Americans use Shakespeare to reflect the things that matter to us most, in the process bringing his plays back to the accessible, bawdy, working-class entertainment they once were. Shakespeare immigrated to America in the saddlebags of the first European settlers. At a time when we are debating the right to own guns, the responsibilities of privilege, racial injustice, and the very character of our nation (all coming to a head in this, a Presidential election year) his work is as relevant to Americans as it has ever been since.

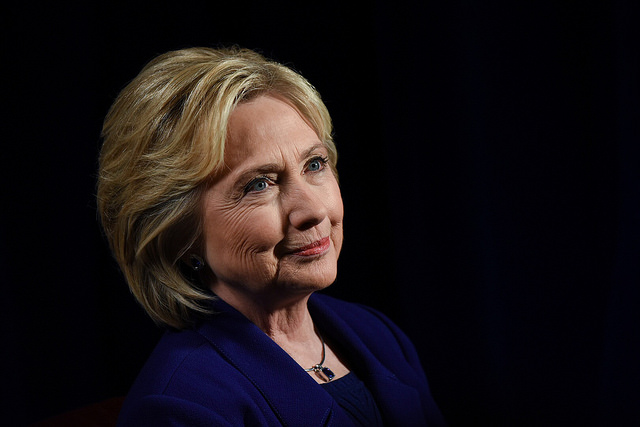

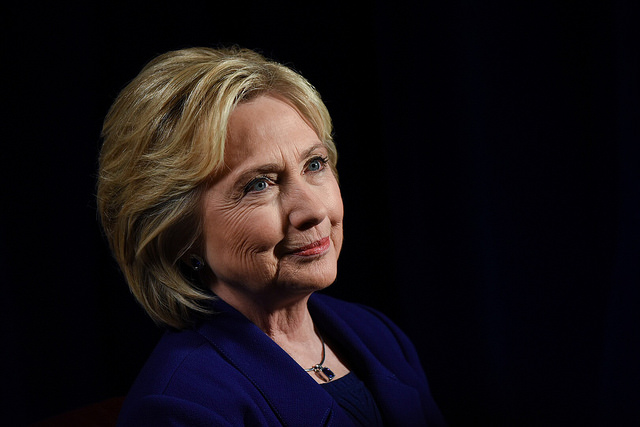

In her op-ed “Hillary in History,” published November 8, 2015, New York Times columnist Gail Collins notes that “when it comes to women winning political office, there’s a long line of wives in the cast of characters.” She calls Clinton a “perfect transitional figure,” representing the intersection of the power behind the throne and the ambition to wield that power herself. And yet this transitional quality, which is almost a job requirement for female candidates, is exactly what makes the Lady Macbeth arrow sting.

The image of Lady Macbeth illustrates the great difficulty of making the transition between wife and leader.

In a 1992 interview for NBC, Katie Couric asked Hillary Clinton, then in her early days as First Lady, to comment on comparisons to Lady Macbeth. Clinton, made wary by the backlash from “cookie gate,” laughs her off. It takes Couric three tries to get a response. Finally, Couric remarks that many Americans are uncomfortable with her perceived level of influence on the President because, “after all, you were not elected.” Clinton, in an olive drab polka-dot dress with an enormous bow at her neck topped by a strand of pearls, nods demurely and lays on the southern drawl: “I don’t know that I have any more influence than anybody else who is an advisor to the president.”

The image of Lady Macbeth illustrates the great difficulty of making the transition between wife and leader. And it draws its power from regressive definitions of those roles.

First ladies have been particularly susceptible to this epithet. Historian Gay Smith writes that “attempts were made to characterize Eleanor Roosevelt as a kind of Lady Macbeth having undue influence over President Franklin Roosevelt’s actions and policies.” Nancy Reagan drew similar criticism, as a Lady Macbeth and “lioness with claws unsheathed.” During the 1980 presidential election one writer argued that “first ladies should be elected, not married” because “they do not just reign with their husbands but play a part in ruling.”

In 1996, Time published a cover photo of Clinton that they later admitted had been manipulated to look like Lady Macbeth.

Despite attempts to shrug her off, Lady Macbeth has dogged Clinton’s political career like some particularly virulent paparazzo. The same year Katie Couric asked Clinton to comment on the public’s “fears of a coequal partnership” in the White House, William Safire described a new parlor game political correspondents in Washington like Maureen Dowd and Andrew Rosenthal played behind closed doors during election season. In his New York Times column, “On Language,” Safire describes the “Shakespeare ‘92” rules as follows: “to match characters in the Bard’s plays with real people in today’s political whirl.” For example, “somebody says, ‘Hillary Clinton’ or ‘Marilyn Quayle,’ and the respondent says, ‘Lady Macbeth’ or ‘Portia,’ as the case and the political judgment may be.” The game was, Safire wrote, an attempt to compare fleeting political celebrities to “eternal” archetypes. A month later, Dowd referenced the Hillary Clinton / Lady Macbeth comparison in a Times piece about Hillary’s “bid” for first lady and America’s “fears of the notion of a coequal couple in the White House.” She writes, “Everywhere Mrs. Clinton went last week the high powered litigator who brought home more than five times the salary her husband did last year tried to reassure doubters that she is not Lady Macbeth in a black preppy headband.”

Three months later, The American Spectator featured a cover story on Hillary Clinton titled “Lady Macbeth of Little Rock.” Conservative critic Daniel Wattenberg observes that “The image of Mrs. Clinton that has crystallized in the public consciousness is, of course, that of Lady Macbeth: consuming ambition, inflexibility of purpose, domination of a pliable husband, and an unsettling lack of tender human feeling, along with the affluent feminist’s contempt for traditional female roles.” In 1996, Time published a cover photo of Clinton that they later admitted had been manipulated to look like Lady Macbeth. The frequency of the comparison spiked in 2008, and now is once more on the rise. In a case of life imitating art imitating life, a recent piece in The Guardian suggests that Hillary Clinton could learn a thing or two from fictional First Lady Claire Underwood. (House of Cards creator Beau Willimon has suggested Claire was based on Lady Macbeth, though Francis seems less like Macbeth than Shakespeare’s version of Richard III).

As a woman, she suffers from a “likeability issue” because she cannot afford to seem maternal without being dismissed as too soft.

Maybe it’s a good sign that Hillary Clinton can joke about these Shakespearean comparisons. Collins quotes Clinton’s retelling of the “if I’d married him” joke so popular among first wives (Michelle Obama has told it, herself):

“[Hillary] Clinton told a joke about a successful businessman and his wife who drive into a gas station where her old boyfriend is working. The husband notes with satisfaction that if she’d married him, she’d be the wife of a gas station attendant.”

“And then,” Clinton concluded, “the wife says: ‘No, if I’d married him he’d be a big success, like you.’”

The danger of being the power behind the throne is that you are considered neither a powerful leader nor a good wife. In his popular book of “political theology,” The King’s Two Bodies, scholar Ernst Kantorowicz described a classic catch-22 of politics, that a leader must be seen as both a father-figure protecting the realm and a nurturing mother who can soothe an anxious people. In this sense Hillary Clinton seems perfectly poised to lead, and yet, as a woman, she suffers from a “likeability issue” because she cannot afford to seem maternal without being dismissed as too soft. This is ultimately what the archetype of Lady Macbeth reveals, the persistence of a retrograde assumption that ambitious women have forfeited the soft, squishy qualities that would make them good mothers, good wives. Or, to quote Lady M. herself, they must “unsex” themselves.

Appearing just after “Lady Luck” in the OED, “Lady Macbeth” is defined as signifying “a remorseless or ruthless woman, esp. one who assists or controls a weak man”; the embodiment of the bad wife. I’d argue this is a stubborn misreading of Shakespeare’s play, a play in which the husband addresses his wife as “my dearest partner in greatness” and relies on her quick thinking to get away with murder (the kind of cool-headed woman who will pick up the bloody daggers her husband foolishly carries away from the crime scene).

The question of Hillary Clinton’s success rests not only on whether she will finally shake the Lady Macbeth associations and overcome the “likeability issue,” but whether we as a nation can reconcile the role of President with that of the Good Wife.