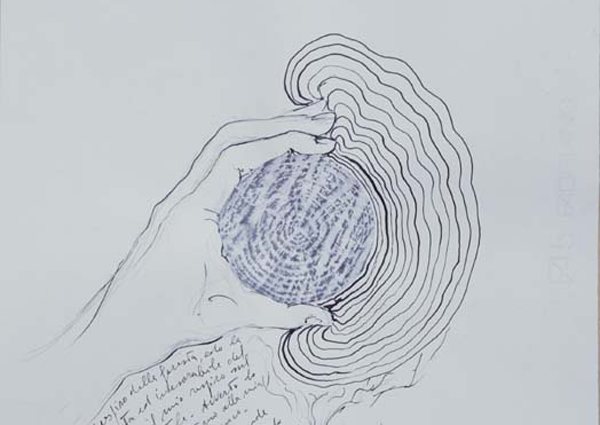

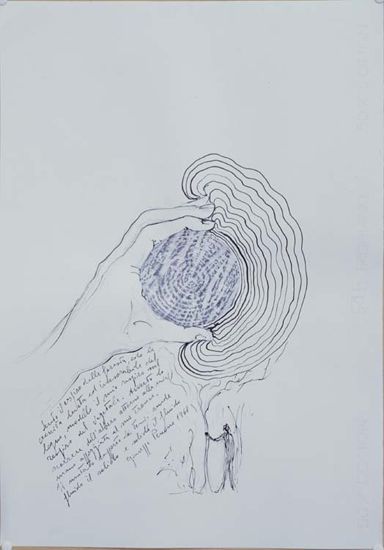

Collection of the artist.

In early autumn it rains pollen in my garden. It falls from the tree by the front door, flickering pale yellow in the sunlight. It’s best to watch in the afternoon, when the bees are at their most active, humming away until darkness falls. When the bees began frequenting this tree many years ago, I panicked. As a child living in England, I was attacked by a swarm whose hive I had disturbed while playing hide and seek in the copse with my brother. I heard the buzzing before I saw them, ribboning toward me as I walked back to our driveway, unable to find my brother. By the time I realized what I had triggered, they had already descended upon me, clinging to the cuffs of my red raincoat, my blue jeans, my lips, my ears.

Hearing my cries, my brother ran out from where he had been hiding, and pushed me into the house, trapping me and the bees between the front door and the glass door that stood behind it. This is where I remained until a neighbor came. I have no recollection of what happened after that. I know honey bees die after stinging their victims. Ironically, I feel guilty.

We planted the humming tree, a terebinth Ella sapling indigenous to this area in the Judean Hills of central Israel, twenty years ago, when I first moved to the Ella Valley. We planted it outside the boundaries of our plot of land, by the driveway. After a few months, I became convinced this was not the right spot for it, and one October morning I dug it up and replanted it in the garden. I loved its mottled trunk, its delicately veined leaves, and could already imagine my children learning to climb its branches. The tree grew slowly. Today, it towers over the house and spreads those branches across the front porch. Today, I am not afraid of bees.

The trees in the area where I grew up, back in northern England, were mostly silver birch. One was planted in the middle of the garden, a winnowy tree that shimmered in the moonlight and shivered in the wind. I loved that tree and would run my hands up and down its slender trunk when I thought no one was looking. I grew up with that tree until age fifteen, when my brother, Andrew, two years older than I, was killed in a motorbike accident. Back then, it seemed as if everything stopped growing. My mother, knowing the wars that Israel had been through, yearned for a place where there were other Jewish mothers whose sons had died. She craved empathy. Within a year, I was sent ahead of my grieving parents to a boarding school in Israel’s Negev Desert, a place where no trees grew. The green landscape of my childhood was replaced by a pale wadi and a rocky expanse that supported only low bushes. I suffered, and got on with life, my memories erased by the arid climate, my connections to family and school friends back in England severed. On an emotional level, this was survival of the fittest, and I survived, somehow.

My parents moved to Israel later that year but the damage was done, our family unit shattered. I had been uprooted and more than thirty years later this sense of displacement continues to disturb me. Since then, I have built a house and have made a family of my own, and have chosen to stay in Israel to remain close to my parents. I have returned to England numerous times with a yearning for the life I left behind, for my brother, the house I was taken away from that still feels like home.

On my last visit, a family friend drove me back there, to my childhood home. The copse has gone and in its place is another house. We approach from the back. Through the trees, I see it. This is my home. This is my bedroom window, and next to it my brother’s. I get out of the car and walk toward the boundaries of the garden. Someone has erected a black iron fence around it. I reach through the bars to touch the bracken that grows there. Wild blackberries poke out between the railings. The end of summer. After school, my brother and I used to pick them, popping them straight into our mouths without washing them.

Perhaps this is how it feels to live in exile, to yearn constantly for a land left behind.

A blond woman opens the door holding a yapping dog in her arms. I’m crying now, the dog is yapping, and my daughter, who accompanied me, places a hand on my shoulder. I’m peering through the open door, looking for the emerald carpet, the second glass door, the heavy bronze curtains of my childhood. “We’re going,” my daughter apologizes to the blond woman without explanation. She does not say a word, just stands there holding the dog and staring at me. More than I want to enter the house, I want to go to the silver birch that stands in the middle of the garden. I go. I stroke its bark. My daughter offers to break me off a piece. No, I say, let it be. The silver birch has grown so much, no longer fragile as it was back then. I want to press my lips to it, align my body to its trunk, breath it in. This tree has a history and I am a part of it. I am losing my mind, I think, as my daughter pulls me away, sobbing, to the waiting car.

Perhaps this is how it feels to live in exile, to yearn constantly for a land left behind. When we moved to the Ella Valley twenty years ago, my partner and I took great care, we thought, not to build on land that might have belonged to Palestinians before the Arab-Israeli war of 1948. I had no wish to take land that might once have belonged to others but I had a very great wish to live here. Somehow, the landscape of this quiet valley reminded me of the vastness of Yorkshire. I took walks in the forest that grows around the village.

I was all about nature back then. On daily walks I began breathing in the trees, breathing in the cyclamen that grows in secret places, the za’atar that releases a musty aroma when rubbed between the fingers. Thomas Merton wrote about living “in simple direct contact with nature.” This is what I did. I began listening to the hidden sounds of the forest: a lizard moving through bushes; the rustle of leaves as a snake slithers between the rocks; the dull beating of birds’ wings as they rise at dawn. On these early morning trips I have witnessed a single hawk circling its prey, and parrots the color of peppermint gliding along the outskirts of the forest.

On one of my first forays, I began distinguishing between the trees: carob, olive, fig, and fragrant almond, straight lines of bushes that give succulent, prickly pear fruits through the fall. They were planted by Palestinians who lived here before 1948, people who lived off the land and who probably loved it as much I do.

This is when I became aware of the remnants of buildings that remain deep in the forest, broken walls made of stone and arched doorways that were built by other people. They walked out of these doorways with their children, not knowing they would never return. Once, while working as a journalist, I interviewed a Palestinian woman living in the Deheishe refugee camp south of Bethlehem. I asked her what she thought about the Law of Return, promulgated in 1951, that grants automatic citizenship to Jews. In answer, she went over to a wooden box and pulled out a large, rusty key, which she then held out to me. “This will always be my home,” she said and I nodded.

Were she able to return, there’s no doubt she would recognize where her home had stood, despite the shifting political and physical landscape of this troubled country. Much of the hilly area that surrounds the Ella Valley, for example, was turned into a forest after 1948. The eucalyptus and Jerusalem pine trees were planted by the Jewish National Fund, an organization authorized to preserve state lands for the benefit of the Jewish people. The fact that this forest was shaped by human hands does not make it any less beautiful to the eye but it does expose the layers of history and culture that lie beneath it. It is not just the roots of trees that lie beneath the earth, but the roots of two peoples fighting each other for their existence. Wendell Berry writes about this in “A Vision”:

If we will have the wisdom to survive,

to stand like slow-growing trees

on a ruined place, renewing, enriching it…

then a long time after we are dead

the lives our lives prepare will live

here, their houses strongly placed

upon the valley sides…

The entire valley is resplendent with evidence of life going back thousands of years. In late 2014 an ancient ritual bath, dating to the second century CE, was discovered when the road running beneath my house underwent construction. Nearby, an equally ancient water cistern was revealed, used during the Jewish rebellion led by Simon Bar Kochba against the Romans.

Razing houses or covering the ground with trees will not erase these lives; they will continue to haunt until such time as they are acknowledged.

The cistern was covered in graffiti scrawled by two Australian soldiers serving in this area during the British Mandate, Corporal Scarlett and Corporal Walsh, Royal Australian Engineers of the Australian Sixth Division. They carved their names and serial numbers in the rock around 1939. They were stationed in the area prior to being sent to France. But France surrendered and so instead they were sent in October 1940 to Egypt, where they fought at the front. What was it like for these two soldiers, so far from home, dusty and tired, dragged into a conflict that was not theirs? As I travel this road today, I wonder about the layers of lives of people who inhabited this area: the Jewish women during Roman times who bathed in privacy once a month in the ritual bath; the Christians under Byzantine rule who pressed oil and made wine; the Palestinians who grazed their sheep on the lower terraces for hundreds of years under the Ottoman Empire; the battles that were fought.

A short drive northwards from my house are the ruins of the Palestinian village of Sar’a, up in the hills. There is little evidence of the people who lived here because their houses were razed to the ground after 1948 by the Israeli government, but blue Mesopotamian irises continue to grow on the grounds of the village cemetery. The custom was to bury the dead with three irises: one placed on the head, one on the stomach, and one by the feet. Today, the succulent buds poke through the earth of the cemetery of Sar’a, as nature continues to both witness and renew.

We build our houses, we make our marks on the land, we plant our trees and raise our children, but we cannot wipe out these layers of lives and we cannot continue to ignore them. There is little I can do to change the bitter status quo. But it is my duty to acknowledge those who came before and to recognize not only their existence but the injustice that accompanied their displacement. If I ignore those who came before me, I am ignoring the fullness of past lives. Razing houses or covering the ground with trees will not erase these lives; they will continue to haunt until such time as they are acknowledged. I return to Wendell Berry’s poem, “Rain,” in which he says:

The path I follow

I can hardly see

it is so faintly trod

and overgrown.

At times, looking,

I fail to find it

among dark trunks, leaves

living and dead.

This is what makes the Ella Valley what it is today. These are paths that other people have walked; this is the land that has nourished body and spirit for thousands of years. This is also the spot where David allegedly fought Goliath, the Philistine from nearby Gat. In the King James Bible it says, “And the Philistines stood on a mountain on the one side, and Israel stood on a mountain on the other side: and there was a valley between them.” Every summer, tourists tumble out of buses parked not far from the Ella Junction to walk along the edge of the now-exhausted stream where David picked up the pebble that killed Goliath. I have never stood there but I have visited the site of the Philistine fortress, Tel Azekah, a flat-topped hill that towers over one side of the valley. Standing there overlooking the valley, watching the cars flashing by on the road below, I can easily visualize David looking up, his eyes dazzled by the sun, about to cement his place in biblical history. “Thou art but a youth,” Saul told him, unable to believe this slip of a boy could defeat a giant.

There’s a Bedouin shepherd called Mustapha who lives here a few months in the year, grazing sheep and goats along the gentle slopes. He wears a Kansas City baseball cap pulled down to protect his face against the glare of the sun and only drinks water when the flock does, at the end of grazing time. He has an iPhone on which he listens to music. Mustapha shows me photos of his family: six children, a wife, another wife, a flimsy building he says is his home. They have satellite TV in the tent they’ve erected up on the hill; it helps them pass the long nights apart from their families until winter sets in. They were removed from the desert land their ancestors lived on. When I ask him if he misses his childhood home, Mustapha simply shrugs.

The Bedouins, unwillingly relocated to shanty towns on the outskirts of Beersheva, have a tacit agreement with the Jewish National Fund: their flocks keep the wild wheat down in exchange for access to the valley at certain times of the year. After that, the sheep and goats are herded onto trucks and taken back to Beersheva for sale. Mustapha knows each and every animal by sight, but never gives them names.

The sheep have big, heaving bodies and black lips. I stood there, my back against a rock, fifty pairs of eyes staring at me, waiting for a sign.

I’ve spent time with Mustapha and the other shepherds, roaming the low hills with them, learning the language of the animals—low, guttural tones that instruct the flock to stop, go, or return to their temporary base about a mile from my house. All you can hear is the sound of dry wheat rustling under hooves, and the occasional barking of dogs that circle the flock. Sometimes migrating birds rise up and the sheep lift their heads, mid-munch, at the disturbance.

On one excursion with Mustapha, which began at dawn, when the air is crisp and the hills are flecked gold and purple, a couple of sheep wandered down a slope. Stay with the flock, Mustapha told me, running off to round up the stragglers, leaving me surrounded by fifty bleating animals. The sheep have big, heaving bodies and black lips. I stood there, my back against a rock, fifty pairs of eyes staring at me, waiting for a sign. I cleared my throat. I was in charge and did not have the faintest idea what to do. The sheep stood there until Mustapha came back up the slope. You’ll never make a shepherd, he said.

But perhaps my son will. Daniel grew up here, at the edge of the forest, and has spent hours wandering around the valley. He knows the names of the plants better than anyone else. He knows how to build a fire and how to extinguish it safely; he knows which mushrooms can be eaten and which are the sweetest forest herbs to put in tea when there is no sugar. He knows how to talk to cows and how to get them to move away by performing an exaggerated curtsey, bowing so deeply that his head almost touches the ground. On a recent walk, we suddenly found ourselves surrounded by a herd of pale brown cows. Daniel, a slight figure in the middle of a clearing, emitted a firm moo and then moved his arms upwards and outwards, as if he were about to fly. Then he bent down low, acknowledging the cows in their own language. They moved off at a leisurely pace.

He understands not only the nature but also the history of this place where he was born. He took his first steps in the forest, which is also where he cultivated his love of nature. He can recognize a mole burrow, and knows when a snake has been hiding under a particular rock. He has crawled through many of the tunnels leading to caves used since the time of King David, three thousand years ago, for refuge and escape. And last week it was Daniel who showed me the rubble of a Palestinian house destroyed after 1948.

It was getting late and the air was heavy with approaching darkness. I looked through two tiny windows set deep into the south-facing wall of the house. The valley stretches out, dotted with olive and carob trees. On a clear day you can see as far as Gaza. “Look,” Daniel said, balancing on a rock, one hand clutching the branch of an almond tree heavy with blossom, “what a view they had back then.”