Fields, country cottages, cow sheds, and tower silos flash by out the window of the bus. The head teacher picks up the microphone, taps on it, blows.

“Are you listening to me, children?”

“Yes!”

“I want to remind you one more time about our plan for today. We’ll drive until it gets dark, stop in the forest for the night, set up the tents, eat supper, and go to bed. Then tomorrow morning we’ll leave in time to arrive in Brest by twelve o’clock.”

“And we’ll bake potatoes?” asks Sinitsina.

“Yes, of course, we’ll bake potatoes, and fry salo… Now, children, do you remember, how many years ago was the defense of Brest Fortress?”

“In ’41, which means forty-six years ago!” yells a teacher’s pet named Kutepova.

Onishchenko says to me, “The guys brought some stove-top vodka. Wanna drink?”

“No. I don’t drink,” I say.

“You don’t smoke and you don’t drink? You’re a picture of health, huh? But you wanna fuck girlies, right? No smoking, no drinking, only fucking all the…”

Nesterenko turns to us. “You’re such a bigmouth, Onishchenko.”

“Why does that make me a bigmouth?”

“You know you are.”

“You want me to prove I’m not a bigmouth?” he smiles. “Wanna try me?”

Nesterenko snorts, turns away.

Onishchenko leans in to my ear and whispers, “You know which of our babes you can fuck? Koltakova. She’s not a virgin anymore. Last summer some guys out in the country did the deed.”

“How do you know?”

“She told me herself. What, you believe me? One zero, my favor. No, seriously, the guys said so. Basically, one guy made like she and him were going for a walk, then he brought her to his house, and then a bunch of his friends arrived and they all came on her belly, on her dress. And she pressed charges.”

“Then what happened?”

“The guys are serving time. What do you figure they got, fifteen years? Since it was a gang rape. Listen, here’s a joke. A man is on trial for gang-raping a bunch of big-horned cattle. He stands up in the courtroom. They ask him, ‘Where are the rest? Where’s the gang?’ He says, ‘I was alone.’”

Onishchenko giggles, I smile.

“Get it?” he asks.

I nod.

We stand in a clearing—me, Onishchenko, Kurilovich, Maleev, and Usachenok. Everybody’s smoking but me.

“Come on, why are you wound so tight? What are you, a virgin?” he says. The guys laugh.

“And you know what I saw over there?” says Maleev. “Tampons. The babes were changing their ’pons, and throwing the old ones out.

“Piss off,” says Usachenok.

“Let’s go—I’ll show you if you don’t believe me.”

Onishchenko asks, “Where were they? What spot?”

“Over there,” Maleev points to a part of the forest.

Onishchenko turns to me. “Let’s go look, Vova.”

“Um, I don’t feel like it.”

“Come on, why are you wound so tight? What are you, a virgin?” he says. The guys laugh. “We’re gonna go now, don’t get started without us,” he says to them.

“There’s nothing to get started with yet, I have to go get it,” Kurilovich says, and goes to the tent.

Onishchenko and I head back to the clearing.

“Did you see them?” Kurilovich asks. He’s holding a green vodka flask in his hand.

“Nah. Gimme a shot,” says Onishchenko.

“I guess you didn’t look in the right place. Take it.”

Onishchenko takes a drink, looks at me. “Wanna swig, Vova? Here you go…”

I take the bottle, put it up to my mouth. It’s got cloudy homebrew vodka in it. The neck of the bottle is wet with slobber. I take a sip, offer the bottle to Kurilovich. Onishchenko intercepts it, takes a big gulp.

“What are you doing, man? Trying to hog it all?” yells Maleev. “You want to be the only one to get loaded?”

“You said there was another bottle…”

“Yeah, and? What then? What about tomorrow?”

“Tomorrow we’ll get some beer.”

“Where you gonna get it?”

“In Brest. I’ll take care of it,” Onishchenko says. “Go get the other one before Teachy spots that we’re missing.”

We go to the bonfire. Onishchenko smiles like a moron, staggers, grabs hold of a tree. It’s not visible on the rest of us. Kurilovich grips Onishchenko’s shoulders.

“Sober up, man. The teacher will spot us. Your stumbling will get all of our asses beat, not just yours.”

“The teacher creature’s got a big red cunt…”

“Shut the fuck up,” Kurilovich tells him. “Your ass is gonna be red and blue.”

The babes and the teacher are sitting by the bonfire frying salo on sticks.

“Why, here are our boys… Where have you been? We were starting to get sad,” the teacher says.

Maleev says, “We’re going to sleep. Since we’re getting up early tomorrow.”

“As you wish. But maybe you’ll come sit with us for a while?”

Nestrenko looks at Sanina with an insidious smile. She’s the prettiest in the class, the best dressed of all. Now she’s in corduroy jeans from Italy and a gray Yugoslavian windbreaker.

Onishchenko sings quietly in my ear: Two football players get out of their truck, lay down on the field, and fuck, fuck, fuck.

Our tent is behind the bus. Onishchenko unzips his fly, pees on the tire. Maleev hollers: “You want the drivers to give it to you?”

“The drivers are faggots, I’ll fuck ’em in the mouth.”

“Seriously, or they’ll fuck you in the mouth, got it?”

Onishchenko zips up his fly, lies down in the tent. Kurilovich says, “What do you think, is he really that drunk? He’s totally full of shit. He didn’t say anything like that in front of the teacher. Well, should we lie down?”

“What the hell else is there to do?” Maleev spits on the ground. “We can’t get any more hammered.”

Maleev and Kurilovich climb in the tent. Usachinok says to me: “Come with me—I’m gonna smoke.”

“Okay,” I say.

Usachenok takes a cigarette from a pack of Stolichnies. “You really don’t want one?” he asks me.

“Really.”

“That’s right, you’re a role model. All right…”

He strikes a match, lights a cigarette, takes a drag. There are noises audible from the bonfire area. Usachenok throws his cigarette.

Koltakova and Kutepova come out into the clearing. “What’s this you’re doing here?” Koltakova says.

“Where’s the teacher?” asks Usachenok.

“She probably got on the bus, to go to sleep…”

Usachenok picks his cigarette up off the ground, takes out his matches.

“What, she’s gonna sleep on the bus?” he asks.

“Yes.”

“Why not with you, in the tent?”

“You should ask her that,” says Koltakova. “You’d better give me a cigarette.”

“You really smoke?”

“Yeah, sometimes I indulge,” she says.

I reach for the pack, too.

“You too, Vova? Go ahead, be a good role model for us…” Usachenok says. “Well, should we go for a walk? Not to the bonfire, don’t piss yourself. This road here goes straight out to the highway.”

“I wanted to ask you,” I say to Koltakova. “They told me about you…”

Usachenok walks in front with Kutekova. Koltakova and I fall behind them about three meters. Cars and vans are going by on the highway. “I wanted to ask you,” I say to Koltakova. “They told me about you…”

“Who told you about it, or is it a secret?”

“It’s a secret.”

“And what did they say, exactly?”

“Well, they said you…last summer, out in the country…”

“Well, what about it?” she says.

“I just wanted to ask, is it true or not?”

“Curiosity killed the cat, you know…” She touches my belly, moves her hand lower and then jerks back after I get a hard-on. She giggles. “Don’t listen to anybody, okay? I’m the only one who knows what really happened, but I don’t have to tell anybody if I don’t want to, got it?”

“Got it.”

“Let’s talk about something else,” she says. “After eighth grade, where are you going? To ninth grade?”

“Well, yeah, where else would I go?” I put my arm around her waist. “And you?”

“I don’t know yet. There’s still time left.”

“How much time is there? It’s the end of May.”

“In a pinch they’ll always take me in ninth, right?”

I slowly move my hand up to her right shoulder. She stops me abruptly, pushes my hand away. “We shouldn’t do this, all right? I’m gonna go to sleep now.”

We go up to the bus. The bonfire has died down. The driver Misha is smoking by the rear tires.

“Where are you going?” he says. “Do you know what time it is? It’s two in the morning.”

“You won’t tell Elena Semyenovna?” says Kutepova. “Please.”

“Don’t piss your pants, I won’t tell,” he says.

The teacher speaks into the microphone: “Now we will all get out and go inside the fortress.”

“Elena Semyenova, may I stay here?” I ask. “I’ve been to the fortress before. And I have a headache.”

“Well, if your head hurts…” she says. “Generally speaking, breaking away from the collective is not a good thing, but, all right…”

I lean back against the seat, close my eyes.

We’re standing by a little fountain. Across the road is a two-story supermarket. Maleev gives Onishchenko a ruble.

“You want two?” Onishchenko asks.

“Yeah.”

“What about you, Vova? You want some beer?”

“Just one.” I give him two fifteen and one twenty kopeck pieces.

“So, three altogether for you guys, if there’s one from Vova, and then two for me,” Onishchenko says. “All right, I’m off.”

Onishchenko goes up to two guys. They’re seventeen or eighteen. One of them has a round button pinned onto his jacket, but from here I can’t see what’s on it.

“It’s no good we sent Runt,” says Kurilovich. “We should have all gone. They’re gonna push him around and take the dough.”

Onishchenko is walking to the store with the local guys.

“Hey man!” Kurilovich screams.

He doesn’t turn around.

“Well?” asks Maleev. “Where’s the beer?”

“There is none,” says Onishchenko. “They figured out we’re from Mogilev and wanted to beat the shit out of us. They were gonna call some more huge guys… I barely got us off the hook. I had to give them the money.”

“Have you lost your fucking mind? All the money?”

“They searched me, took me to the store and searched me.”

“Now I’m gonna fucking kill you,” Maleev hollers. “We should have each got our own—I’ll bet the store would have sold to us.”

I’m sitting by the tent, reading a book, The Andromeda Nebula. Maleev comes up to me.

“Vova, come here. We need to talk.”

I put a bookmark between the pages, shut the book, and get up.

We go out to the clearing. Standing there are Onishchenko, Usachenok, Kurilovich, and Koltakova. Maleev grabs Koltakova’s hand. “So? Did he fuck you or not?” he says.

She snatches her hand back. “None of your business, got it? And just try and touch me, by god…”

“Don’t try to scare me…” says Maleev.

“I’m not trying to scare you. You’ll see for yourself if you try anything,” she says.

Koltakova goes to the bus. Everybody looks at me. Onishchenko smiles crudely. Maleev says, “You think you’re so smart, right? And the rest of us are morons?”

“So what?” I say.

“Nothing.”

He puts his hand up abruptly, and I flinch.

“Don’t be scared, we’re not gonna hit you,” he says. “We’re just going to teach you a little lesson.”

“Take him down! Dogpile!” Kurilovich screams.

I knock on the door of the bus. The head teacher opens it.

“Elena Semenova, may I sleep in the bus? The tent feels cold to me.”

“Why is your jacket all wet? And all stained green?” she asks me.

“I slipped.”

“All right, come in…”

There are newspapers spread out on the front seat, and on it are slices of salo, boiled eggs, bread, pickles.

Misha, the second driver Valery, and the geography teacher Prudnikova are sitting in the aisle.

I lie down on the wide seat in the rear of the bus.

The head teacher says to Misha, not very loudly: “He’s a good student… Mother’s on the parents’ committee… We can’t, not now…”

Misha mumbles something, rustles some papers. Their glasses clink.

I’m pulling my sneakers on. My feet swelled during the night. I can hardly get them on. Misha and the head teacher are asleep on the first seat, their arms around each other. Valery and Prudnikova are also together, in the aisle. Two empty vodka bottles are lying on the floor.

“Where did you sleep, on the bus? Come on, don’t be mad about that. Come with me, I want to show you something…”

I’m careful not to wake them up opening the door of the bus. It’s cold. I zip up my jacket.

Onishchenko is smoking by the tent.

“Hi!” He shoves his hand at me, I shake it. “Where did you sleep, on the bus? Come on, don’t be mad about that. Come with me, I want to show you something…”

“Tampons?” I ask.

“What fucking tampons? What are you, a moron?” He laughs.

We walk along the forest on the side of the road. Onishchenko stops. “Give me your word, as one of the brothers, that you won’t tell anybody,” he says.

“My word as a brother.”

“Swear on your tooth.”

I touch my front tooth with my fingernail.

He shoves his hand in his pocket, takes out a button pin. It says “Modern Talking” and it’s got Thomas Anders and Dieter Bohlen from the German rock group on it.

“I bought it yesterday from those guys.”

“For how much?”

“Four rubles.”

“So, like, they didn’t take your money?

“No,” he said. “But you swore on your tooth that you wouldn’t tell anybody. That’s it, let’s go back.”

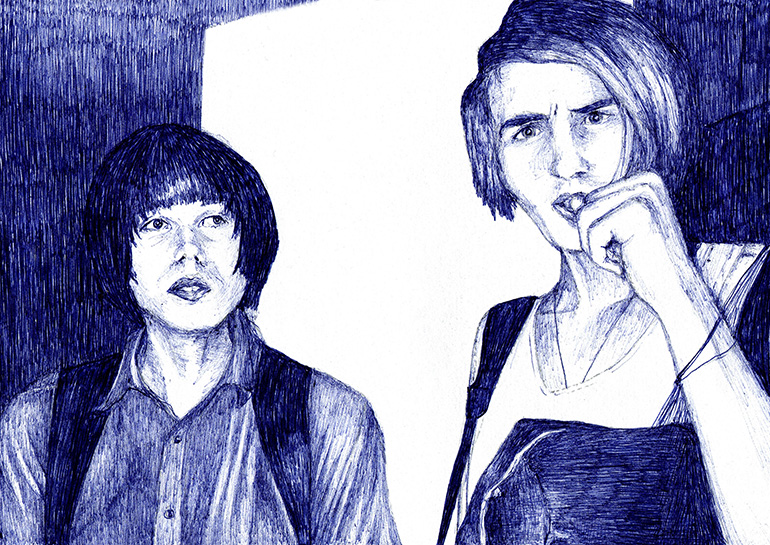

Vladimir Kozlov grew up in Mogilev, an industrial city in what was then the Belarussian Soviet Socialist Republic and is now the country of Belarus. He has published more than a dozen books of fiction and nonfiction. Several of his novels have been long-listed for awards, such as the National Bestseller and Big Book prizes in Russia. He was also nominated for GQ Russia’s Writer of the Year in 2011 and 2012. His most recent novel Voina (War) was released in 2013, and he also wrote, directed, and co-produced a feature-length independent film adaptation of his novella Desyatka (Number Ten). He lives in Moscow, and is nearing completion on a documentary about the Siberian punk movement of the 1980s.

Andrea Gregovich’s translations of Kozlov and others have appeared in AGNI, Tin House, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Café Irreal, 3AM Magazine, BODY, and several anthologies. Her translations of Kozlov’s story “Politics” appears in Best European Fiction 2014, and her translation of Desyatka (Number Ten) is available as a Kindle e-book. She is also writing a book about her grandfather, a notorious Arizona cowboy who was one of the first pilots in history to experiment with cloud-seeding.