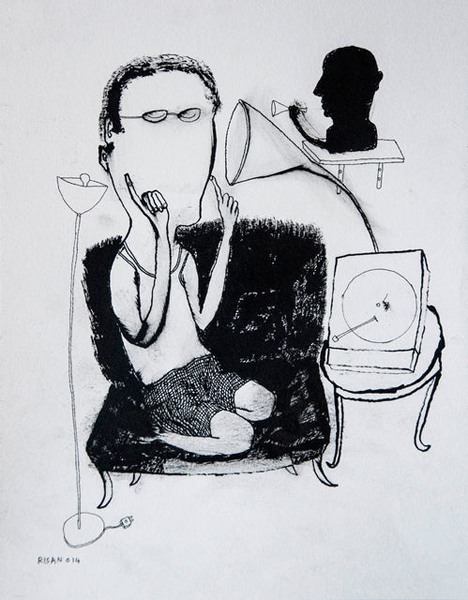

Whenever the uncle we all called Gramophone, behind his back, walked into any room with a radio on or some music playing, it was immediately turned down or turned off. He would sometimes use two fingers to block both ears when loud music from the record store down the road wafted into the Family House. He was called Gramophone because he would clean and dust every part of the sitting room but would not go near or touch Grandfather’s four-in-one Sanyo stereo. When this was pointed out to him once, he shrank back and said he could dust and clean everything in the sitting room but not that Gramophone, pointing to the Sanyo stereo. We were warned not to whistle songs around him. Whistling was not encouraged in the Family House at any rate; whistling in the daytime was said to attract snakes while whistling at night attracted evil spirits.

He sought refuge in the Family House many years ago, having killed a man, or, as we were told, he had not actually killed the man but the man had died from their encounter and he had had to flee from the village at night. He knew that there was only one place on this earth where no arm no matter how long could reach him, and that was the Family House.

Anytime someone sang any popular song around him, he would cover both ears with his hands like a little child who did not want to hear or listen to an instruction. On days that Grandpa was happy, he hung the loudspeaker of his Sanyo stereo on the outside wall of the house facing the street so that passersby could hear the music playing. Many would stand and listen to the music for a while. Grandpa usually did this when a new LP was released by any of the popular musicians. When a new LP was released, Grandpa bought the record and played it over and over again while a small crowd stood outside enjoying the music. Some in the crowd whispered that this was what it meant to be a rich man. They praised Grandpa for not being selfish. He actually spreads his wealth, so that even those who have no music system can stand in front of his house and enjoy the music, they said.

On such days Gramophone would go to his room and plug his ears with cotton wool and would not emerge until late at night, when the hubbub had died down and the music turned off. When he emerged his eyes would be red and would appear as if he had just finished crying. Those who knew in the Family House would shake their heads. They were the ones who told us his story in bits and pieces, but at the heart of the story was a gramophone record player.

He used to live in the village and was the first man to buy a gramophone record player. His nickname back then was Cash. He was also the owner of I Sold in Cash Provision Store.

In the evenings when people were back from the farms and had finished the day’s business, they would sit outside their homes to take in the cool night breeze. Cash would tie his gramophone to the passenger seat of his bicycle and would pedal slowly through the village. As he pedaled past homes, people would call out, Cash, Cash. If it was their lucky day, he would gently alight from his bicycle and untie his gramophone. A table would be produced and a piece of antimacassar spread on top of the table on which he would then gently place the gramophone like the special guest that it was. His hosts for the evening would request whatever record they wanted played. A favorite was a play featuring Mama Jigida and Papa Jigida, a bickering couple who quarreled all the time because Papa Jigida was always broke. Sometimes people requested some local musical star. Cash would search through his collection and say, I don’t have the record by that particular musician but I have this one and they both play their guitar in the same way. Listen to it, you’ll like it.

Whoever thought of putting people in that box must indeed be a wizard, one of the householders would remark.

Cash was always a welcome guest and people would bring out their best drinks and kola nuts to entertain him. A few would even put some money by the record changer for him to buy batteries. For many, just having the gramophone sitting there was enough. For first-timers Cash would flip through his pack of LPs arranged in a carton and pick out something. He would bring out the LP, dust it with an orange cotton handkerchief, and gingerly place the record in the changer. First there was a little crackle as the pin scratched the record and then the voices would begin to sing or talk and would float into the surrounding inky darkness.

Whoever thought of putting people in that box must indeed be a wizard, one of the householders would remark. That is what I keep telling our people, the white people have their own witchcraft but they don’t kill their brothers and sisters with it, they invent things like the airplane and the car and this gramophone.

At this point a bottle of half-drunk aromatic schnapps still in its original carton would appear, and drinking would commence while the gramophone made music. Cash would occasionally bring out a record to play. He would begin by introducing the musician. Some of the artists were from the Congo and sang in Lingala. Even though Cash had never been to Congo, he would sometimes translate these songs, especially after a few shots of schnapps:

My mother saved and scraped to buy me a guitar

I will never forget my mother’s sacrifice

I will play this guitar until I die.

Rotate Provision and Fancy Store was everything Cash Provision Store wasn’t. Take the word Fancy that was a part of its name. People wondered what the word Fancy meant at first, but were not left to wonder for long. Not only did Rotate stock and sell provisions, but he also sold baby clothes, and women’s hats and gowns and shoes—these were the fancy goods, according to him.

Cash prided himself on the fact that he sold in cash, hence his nickname, as opposed to credit. Rotate did not mind offering credit and would quickly write down the customer’s name and how much was owed in a blue-ruled Olympic Exercise notebook. The only proviso was that customers had to pay a little against what they owed before he could offer more credit.

Rotate installed his own gramophone in his store and hung both loudspeakers from the door. His gramophone was always playing music. He played not only highlife, but also some Western music by KC and the Sunshine Band and Sonya Spence and Don Williams and Skeeter Davis and Bobby Bare.

A bottle of watered-down gin filled with anti-malaria herbs was placed on a table in the store. Customers who had no money could have a free shot of watered-down gin, listen to music, and chat. Some ended up buying an item even if it was just a cigarette.

While Cash closed his store as soon as darkness came, Rotate lived in his store and encouraged people to knock on his window at any time if they needed to buy something. Rotate also had a medicine box out of which he sold tablets. Just tell him what ails you and he’ll mix some tablets that’ll cure you, people said about Rotate.

People no longer talked in whispers about how Rotate got his name or made the money with which he had opened his Provision and Fancy Store. They all knew he had made his money from a marijuana farm. When news of the farm reached the ears of the police, a detachment of policemen was sent to arrest him. According to people who were there, the police inspector who led the team asked Rotate if he did not know that it was illegal to plant marijuana.

“No, sir, I did nothing wrong. I was only practicing crop rotation.”

“What do you mean by crop rotation?”

“Well, sir, in school we were taught in agricultural science that it was not good for the soil to plant only one kind of crop from year to year so I decided to rotate the crops. Yam last year, marijuana this year, and corn next year,” he shot back.

He was arrested and detained at the police headquarters, but he bribed the police and was released.

When Cash heard that another store had opened he went to congratulate the new owner and even sat down ready to share drinks. He knew Rotate’s story. Unlike Rotate, he had made his own money by using his bicycle to ferry items to distant markets for female traders. But he believed in live and let live. Rotate did not offer Cash any drinks. According to Cash, the man rejected his extended hand of fellowship.

Cash began to worry when he noticed that items on his shelf were beginning to expire without being sold. Biscuits, tea bags, tins of milk all sat on the shelves until they expired. He stopped moving around with his gramophone in the evenings to people’s homes, preferring to stay in his store and play the records in the hope that customers would come in to buy. Rotate’s store, on the other hand, was attracting the younger crowd, which had money to spend and spent it quickly, unlike the older people who counted every penny and loved to haggle.

Cash began to introduce new things. He now sold chinchin and puff-puff and buns in a glass-sided display box, but Rotate had beer-beef—chunky pieces of beef spiced up and fried until they were really dry and filled the mouth—that were said to enhance the taste of beer on the tongue when chewed. Rotate sold sausage rolls, which had the advantage of never going bad. Rotate only bought and sold certain items during certain seasons. Schoolbooks and exercise books when school resumed in September, machetes and hoes at the start of the farming season, raincoats and boots at the start of the rainy season, and Robb, Mentholatum, and Vicks inhalers when the harmattan season set in. Whereas Cash would pile up all the items in his store even when they were out of season and sometimes even sold brown and faded exercise books to pupils at the beginning of the school year, the stuff from Rotate’s store always smelled fresh and new.

People began to talk about the fall of Cash and the rise of Rotate.

And then Rotate bought a Yamaha motorcycle, an Electric 125. It was electric blue in color and flew through the dusty village footpaths like a bird. It made Cash’s Whitehorse Raleigh bicycle look shabby and prehistoric.

People began to talk about the fall of Cash and the rise of Rotate. Cash had a framed picture in his store that showed two men. In one half of the picture, the man who sold in cash was smiling and looking prosperous in a green jacket and a fine waistcoat with a gold watch dangling from a chain and gold coins all around him. The other man, who sold on credit, was dressed in rags and looked haggard. All around him were the signs of his poverty; a rat nibbled at a piece of dry cheese in a corner of the store. A wag suggested that Cash should change his name to Mr. Credit.

Someone came and whispered to Cash that the reason his former customers were running away from his store was that Rotate had been spreading terrible rumors about him. He said that Rotate told people that Cash opened the soft drinks he sold and mixed them with water in order to get more drinks, that he duplicated keys to padlocks before he sold them.

Cash was angry when he heard these stories and decided to confront Rotate. His plan was to tell Rotate that the sky was wide enough for every manner of bird to fly without running into each other or knocking each other down with their wings. His plan was to tell Rotate that they could indeed practice rotation in their business by taking turns selling certain items so that they didn’t create a glut. But Cash’s visit was unsuccessful. Rotate rebuffed him, telling Cash, There is no paddy in the jungle, you mind your business, I mind my own. Every man for himself, God for us all.

One day there was an early-morning police raid on Rotate. They knew exactly where to look and they found wraps of marijuana in empty giant tins of cocoa beverage. According to some people, the leader of the team told Rotate to give out everything in his store because this time he was not coming back.

But Rotate did come back after three weeks and he promptly declared total war on Cash, claiming that Cash had ratted him out. Rotate returned from detention red-eyed. He said he was going to wipe out his enemies once and for all. When you kill a snake, there is no need to leave the head lying around, you must sever the head and bury it in a deep pit, he boasted. He told his customers to buy only from him; if there was something they needed and he didn’t have it, he would buy it for them the next time he went to the market.

According to Rotate, there were only two kinds of people in this world: those who were for Rotate and those who were against him. He said that there was no way the police could have known where he kept his marijuana cache if someone had not worked as an informant. He said if his enemies were jealous because he was the owner of an ordinary motorcycle, then what were they going to do when he bought the fully air-conditioned Peugeot 504 station wagon that he was going to get soon? Though Rotate had dropped out of secondary school early in form three, he still threw around terms from the various subjects he had studied and justified his nefarious trade in marijuana by quoting the law of demand and supply. He said having only one store in the village was the equivalent of creating a monopoly. He said he believed in democracy, which was why he played his gramophone for all, unlike Cash, who only played for his favorites. He said he was planning on expanding his business and bringing democracy to the village. He planned to expand his business and open a full-fledged boutique selling ladies’ and children’s clothes and would also open a chemist shop selling medications. He said he was practicing what he had learned in his business-methods class in school.

Cash did his best to reach out to Rotate. He sent a couple of individuals who were close to Rotate, the people who bought marijuana from him. Rotate said to them, “The police told me that the person who told them about me and my business told them to lock me up for good, that he did not want them to ever release me from detention. Think of what would have happened if I was never released. Who else could possibly tell them that?”

Soon after his release, Rotate bought an electric generator and a fridge and began to sell cold drinks. Cash had a gas lamp in his store and this was considered a major boost in a village where darkness descended without warning and was impenetrable and dense. But people also told Rotate that the two records Cash played over and over again were songs in which the musicians talked about enemies. One of the songs had the refrain:

You are not the owner of my destiny

Your hatred of me, and your anger against me will kill you.

We had never seen Grandpa dance, but he always told us that the day Gramophone got married he would dance and dance. When we asked Grandpa why he did not dance he would respond, If you give me a reason to dance I will dance. Win a scholarship to study in England and I will dance. If you people give me a good reason to dance I will dance. The only person that dances for no reason is the madman down the street, and even the madman has a reason, it is only that we don’t know his reason. But the day your uncle gets married, I will dance for the whole world to see.

Cash would later tell people that when he walked into Rotate’s store that evening, he went in to make peace. To talk to Rotate as one man to another. He had hoped that they could work things out and settle their differences once and for all over drinks. When Cash walked into Rotate’s shop and greeted Rotate, Rotate did not respond to the greeting but said to Cash:

“You are not yet satisfied with informing on me and setting the police after me. You are not satisfied with spreading rumors about me. You are not satisfied with lowering your prices so that people will stop buying from me and buy from you, no you are not satisfied and now you have come to greet me with juju, or you think I don’t know who your juju man is, you think the moment you open your mouth to greet me and I respond I will now become a zombie, and slavishly do all your bidding.”

As Rotate said this he came out of his shop and gave Cash a shove. Cash shoved Rotate back. Rotate slumped and fell to the ground. As he lay on the ground, his entire frame shook a couple of times, a little foam-like thing came out of the side of his mouth, his eyes rolled back into his head, and he stopped breathing.

That night a neighbor came to Cash’s house and asked Cash whether he was waiting for the police to come and get him and send him to jail for the rest of his life. If you know what is good for you, you better start running to the house they call the Family House. You know the big man’s house in the city. No one can touch you there.

That was how Cash came to live in the Family House. He was the one who knew where everything was. If an item was misplaced he knew where to find it. If a lightbulb needed to be fixed or the television antennae needed to be turned or there was a hard task that no one else could do in the Family House, he was the man for the job. He had a bunch of keys with him at all times.

The case did not go away. Rotate’s people did not give up. They called the police and Cash was charged in absentia with murder. Grandpa tried persuading them to reduce the charge to manslaughter so Cash could serve a few years in prison and be released, but the family refused. After many years, Rotate’s uncle, who was at the head of the family’s pursuit of justice, died. His relations who were left were tired of the case and the cost of going to court. Many big stores were now in the village and the story of Cash and Rotate’s rivalry seemed like an ancient folktale. Some people from Rotate’s family soon sent an emissary to Grandpa saying that they wanted a settlement. Rotate had died single. The family wanted money to be paid, enough money to cover the cost of him marrying a wife, and they wanted many white animals, a white cow, a white goat, a white sheep, a white chicken, or the cash equivalent. Grandpa called them for a meeting and the settlement was negotiated down. Eventually they accepted. They were paid. They in turn paid off the police and told the police to close the case.

We were spending the holidays in the Family House the day the man formerly known as Cash, now Gramophone, got married. Grandpa had given him one of the girls who lived in the house. Her father had owed Grandpa some money and she had come to live in the Family House until the debt was paid off. We were told that by the time her father was ready to repay the debt the girl said she did not want to return to her father’s house anymore. Some other person said that her father had died and nobody had bothered to come for the girl after that.

I remember that at some point in the night the man in charge of the music had wanted to turn off the music, but Grandpa had instructed that it be played until morning.

On the day that Gramophone got married, there was a big party in the Family House. The entire street was invited and there was lots of music, but he did not block his ears when he was led out to dance with the bride. Grandpa also danced and danced. The kids from the poorer houses were so excited to have bottles of soft drinks to themselves. They were urged to drink as many as they wanted. Some of them had so many drinks and poured some away and screamed to each other excitedly about pouring a half-finished bottle of soft drink away.

I remember that at some point in the night the man in charge of the music had wanted to turn off the music, but Grandpa had instructed that it be played until morning. As we rolled in our sleep toward morning we could still hear the music playing in front of the family house.

In time Gramophone/Cash had children and told Grandpa that he wanted to return to the village. This is your home now, Grandpa said to him. His children soon joined the many children who lived in the Family House and would grow up to work for Grandpa.