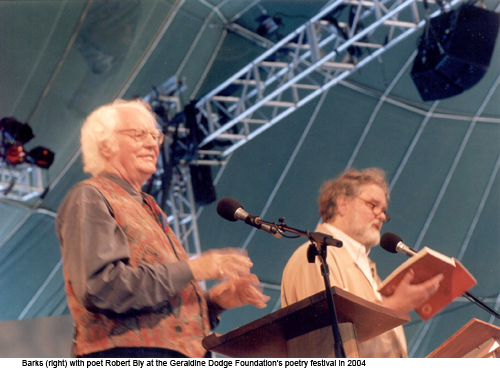

In 1976, the poet Robert Bly handed Coleman Barks a volume of stilted translations by a Cambridge Islamicist named A.J. Arberry and said, “These poems need to be released from their cages.” Since that time, Barks has been translating the ecstatic poems of Jelaluddin Rumi, a 13th century Sufi master and the original whirling dervish. Barks has called himself an “unaffiliated mystic” and translating Rumi has been his own kind of spiritual and poetic practice. With over 15 volumes of translations in print, Barks has helped make Rumi one of the most popular and best-selling poets in the United States.

Born and raised in Chattanooga near the Tennessee River, Barks spent much of his childhood on the campus of the Baylor School, where his father was the headmaster and where he grew up loving words, dancing, and the old oaks, black locusts, and persimmon trees that provided shade. He now lives not too far from the University of Georgia, where he taught poetry and creative writing for over 30 years.

Barks has a big, southern-inflected, convulsive way of laughing that frequently punctuates his sentences. It’s hard not to join in because he seems to be having so much fun considering Rumi’s teachings and what they tell us about life’s ecstasies and absurdities, large and small.

I spoke with him on the phone from his home in the Five Points neighborhood of Athens, Georgia.

–Gibson Fay-LeBlanc for Guernica

Guernica: What will you be doing on September 30, 2007, the 800th anniversary of Rumi’s birth?

Coleman Barks: There are going to be Rumi festivals all over the place, in Charleston, in Prague, and I’ll be at one in Detroit that day.

Guernica: You also just passed the 30-year anniversary of when you began translating Rumi. Did you have any idea when you first started doing this that it would be such a huge undertaking?

Coleman Barks: I didn’t. I started doing it as a practice for myself. And, it still is that. I didn’t have any idea about publishing until about seven years later. It was a late afternoon practice that I did to heal myself from teaching. If you teach three university courses a day, you need something to turn your mind off. I went down to this little restaurant called “Bluebird” and worked on these poems because, to me, they felt like they could not be explicated. I’d been talking all day about what poems meant, and these poems felt like they were mediums you could swim in or float in. They were beyond the mind and that was good for me.

Guernica: Did you know anything about Sufism or mysticism at the time?

Coleman Barks: I had always wanted to. I had read Evelyn Underhill’s collection of mystics and Rudolf Otto and Rollo May. I had been a kind of natural mystic my whole life, growing up there in Tennessee next to the river. Somehow, that was important for my consciousness. I still don’t study [mysticism]. I just wait for experiences.

“Just being sentient and in a body with the sun coming up is a state of rapture.”

Guernica: Other than Rumi, who are the poets you go back to again and again?

Coleman Barks: Wordsworth and Whitman and Rilke. And a wonderful Korean poet I’ve just found named Ko Un. There’s a book called 10,000 Lives. I met him last fall—when you meet the man, something deep in you relaxes. That’s one of the ways I know that something is happening.

Guernica: In your experience, are the spiritual and poetic worlds overlapping, separate, or one?

Coleman Barks: The mystics always say that the experience they’re talking about is ineffable, that you can’t say it. Rumi was asked one time why he talked so much about silence. He said, “The radiant one inside me has never said a word.” One of his metaphors is that all language can say about the divine is “Well, He’s not a weaver.” He said that those who love words have to go toward the divine center using words—you have to use whatever it is you love because the divine is right in there between you and your desire. I love that. It’s like Joe Campbell saying, “Follow your bliss.” You just follow whatever it is you love to do.

Guernica: So translating Rumi is still part of your daily practice?

Coleman Barks: He wasn’t today. [Laughs] I’ll bet a third of the days between the fall of 1976 and now have had either 15 minutes or an hour or three hours of work on Rumi. I have piles of things around that haven’t been published.

Guernica: Have there been periods when you couldn’t translate Rumi for one reason or another, be it spiritual or psychological? Have there been times when you didn’t love Rumi?

Coleman Barks: It looks like there would have been. It seems inhuman to say that I’ve never gotten tired of it. But, I can’t think of such a period. It keeps unfolding in different ways.

Guernica: In your translation, Rumi writes, “Submit to a daily practice.” What are your other daily practices?

Coleman Barks: I like to walk around my neighborhood, late in the afternoon. I sometimes wind up at the wonderful, old Shell station that’s been changed into a coffee shop. Right where Johnny used to change my oil, I have a latte and take out my little book bag. It doesn’t sound very austere. [Laughs]

Guernica: It doesn’t need to be, right?

Coleman Barks: I’m hoping so. I walk down there and read Ko Un or somebody or write on my own. I’m trying to put together three different manuscripts right now.

Guernica: Is that your own stuff or Rumi or . . . ?

Coleman Barks: One is this Rumi book called Bridge to the Soul —the introduction is about this trip that Robert Bly and I took to Tehran and two other cities in Iran last May. There are 90 new Rumi poems in there that haven’t been published. And then, the University of Georgia has asked me to put together a collection of several volumes of my poetry that they’re going to look at. So, there’s all these things going concurrently.

Guernica: I would imagine after all this time that Rumi is like another voice in your head. Do you find him creeping into your own work as well?

Coleman Barks: It’s like being in an apprenticeship to a master. I’ll let someone else say whether or not it seeps into my work. The way I usually try to explain it is with the Rumi work, I try to get out of the way and disappear, and with my own work, I try to get in the way. I let my shame and ecstasy and disappointment come in, all my emotional states, whereas with Rumi they’re more spiritual states.

“ . . . this is a sacred universe to him and to me too. It’s insane not to say that, I mean, just look.”

Guernica: Rumi writes, “Wash yourself of yourself.” How do you do that? There’s a lot of autobiographical poetry out there . . .

Coleman Barks: I think my life is tremendously interesting [Laughs], and surely, other people do too, and, by the way, here are my grandchildren. [Laughs] I’m still shamelessly full of my own effects, of my own existence, so it’s a kind of relief to me to work with Rumi, with something beyond me. The voice that comes there isn’t a personal voice—it’s something more like the voice you hear in Rilke’s Duino Elegies. Not personal. It may be bewildered, it may be ecstatic, it may be blocked in some way, but it’s not necessarily a personal thing.

It’s a difficult thing to talk about, the dissolution of the ego, which all religions recommend—that you somehow die before you die. You get born again, let the Buddha nature take over. There’s some kind of dissolving there that Rumi is always talking about with various metaphors.

One of his great states of awareness that he can’t really talk about—but he goes ahead and talks about it anyway—is called “kibriya.” It’s the Farsi word for splendor or some kind of magnificence or grandeur. He says that it’s activated when the sun comes up. Just being sentient and in a body with the sun coming up is a state of rapture. It’s also a state of kingliness. We don’t have a word for it in English. It may be what is indicated by the inside of a cathedral, what Jesus called, “The kingdom of God is within you.” That sort of vast inwardness.

[Rumi’s] got a very quiet poem about the sun coming up, how they’ve stayed up all night doing this very hard opening practice. He says this state of awareness we have now isn’t imagination. This is not grief or joy, not a judging state, an elation, or sadness—those come and go. All those things I would write about in my own work. Those come and go. This is the presence that doesn’t. He talks to his scribe and says, “Here we are inside the friend”—that’s one of the words they have for the beloved—“that’s inner and outer at once.” Inside the senses and beyond them.

He says the longing for this state of grandeur is what created the body, cell by cell, like bees building a honeycomb. The universe and the human body came from this, not this from the human body and the universe. In other words, they’ve reached a state of awareness that’s somehow prior to the existence of the universe and the source of it. That’s quite a claim to make. That ineffability is right there in that core of awareness that somehow we are reminded of by sunlight.

That was [Rumi’s] teacher’s name—Shams means “the sun.” Anytime he mentions the sun, he means sunlight and the presence that teaches him, which came out of the east, out of Tabriz. It’s all one metaphor. Anytime he mentions the sun, it’s secret language for his teacher.

There’s hardly anything you can say about Shams, he’s beyond all categories. My feeling is that’s what this poetry is and why it’s so powerful is that somehow Shams’s presence is in it. Robert Bly says he’s like “Thoreau times 700.” He’s this wild, fiery, meditating intelligence that brought Rumi beyond all religious categories. Anything that happens, it’s all part of the teaching. That’s way beyond Christianity and Islam.

Guernica: Are these some of the reasons why Rumi has become so popular in your translations?

Coleman Barks: He was popular all over the world, before he began to be translated into English in the late 19th century and more in the 1920s and ’40s and ’50s. There were two men, Cambridge Islamicists, Reynold Nicholson and A.J. Arberry, who brought him over in these scholarly translations, which I picked up in the late ’70s and began to rephrase. A lot of people did then too.

They say that all religions came to [Rumi’s] funeral in 1273. When asked why, they said he deepens us wherever we are, wherever the experience of the sacred is, this “valuableness” in experience. It’s obvious that this is a sacred universe to him and to me too. It’s insane not to say that, I mean, just look. [Laughs] And, laughter’s such an important part of his world view. He has said that it may be that the divine is the impulse to laugh and that we are all the different ways of laughing. Each human form or animal form or shape is a way of God’s laughing.

“There’s some sort of exchange that goes on between human beings that is one of the highest things we do.”

Guernica: You’ve talked about “sema,” or deep listening to text, music, and movement. What separates deep listening from, say, reading Salinger on the subway, or listening to an iPod, or going for a jog?

Coleman Barks: Sometimes, they may not be separate. You might be reading Salinger on the subway and be in deep sema. He was one of my sacred texts back in the ’50s. They’ve been experimenting with that for thousands of years and writing about it too, about what you feel when you’re in a deep state of listening. Some kind of generosity comes in. And, maybe, this state of grandeur.

Have you seen this book A Year with Rumi? I’ve got an introduction in there that tries to talk about what different people’s “soul books” have been. I speculate, and I did some research too, about those books that nourish you in some deep way. For Emerson, it was Montaigne’s Essays. For Hemingway, it was Turgenev’s A Sportsman’s Sketches. Chekhov for Raymond Carver. Dickens for Faulkner. Taoist poetry for Robert Bly. Ruskin and Crabb Robinson for Mary Oliver. Euripedes for C.S. Lewis.

That’s what this work with Rumi has been for me. It’s been a wild “soul book” that I go off somewhere into seclusion with and open myself to whatever that is. I think other people use Rumi that way too.

Guernica: Of Rumi’s Mathnavi, you write, “The other reveals us.” How has translating Rumi revealed you?

Coleman Barks: It’s deepened me somehow. You know the word, “nafs,” desires? I think it’s changed my nafs, [Laughs] or maybe, they changed over time. It’s made my desires different than they were 30 years ago, when I started this. They’re much simpler now, the things I want. I seem more satisfied with simple things.

I think it’s made friendship more important to me. For Rumi and Shams, friendship is a kind of way. That seems very important to me, that quietness of being connected to other people. Some Sufi circles say there are three ways of approaching the divine—one is prayer, one is meditation, and above that is conversation. There’s some sort of exchange that goes on between human beings that is one of the highest things we do.

Guernica: Are there particular friendships in your life that you would point to?

Coleman Barks: I had a teacher who came to me in a dream, and then, I met him about a year after that. That was a pretty good conversation that we had. [Laughs] He said to me, when he first met me, “Will you meet with me on the inside or on the outside?” I didn’t know what I was meeting. In kind of a tricky, intellectual way, I said, “Isn’t it always both?” I should have said, “Inside, now.” I didn’t know what he was offering me.

This man’s name was Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, he was a Sri Lankan teacher, who came over here in the early ’70s, and I met him in ’78. I read him a few [ of my translations]. He said this work has to be done. I claim that he’s helping with it, even though he died in 1986.

“It’s such a foolish thing to argue about names, when what we’re doing is all one thing.”

Guernica: Rumi’s poems constantly loop back to emptiness and silence, “that disciplined silence,” he calls it. Do you have to cultivate that silence in order to translate his work?

Coleman Barks: If I’m not in the receptive place, [it won’t work], but it seems like a place I want to go. It’s like going to sleep when you’re tired, you just do it. You fall into it. It’s a beautiful lucid dream that has language that I can fiddle with.

Guernica: What would Rumi be doing if he were alive today?

Coleman Barks: About his poetry, he said once that he only does it because his friends like it. It’s like fixing tripe for him. It’s not something he likes particularly, but his friends like it, so he cooks it. He had come down out of Afghanistan to Anatolia, Turkey. He said the people there liked poetry. He said that if he had stayed up in the mountains, he would have been doing something else that did not involve language. Maybe, something more theoretical, philosophical, he didn’t specify. He said he’s only doing the poetry because he’s in this particular place, this particular time. That’s kind of discouraging. [Laughs]

Guernica: Rumi’s line “Dance in the middle of the fighting” seems especially outrageous and appropriate for today’s world.

Coleman Barks: I don’t know how you do that. We have the Cyclorama down here in Atlanta. You go in and see the Civil War. I wonder if we set up a Baghdad cyclorama, so people could see the fighting that’s going on right now. Make Baghdad a sort of a theme park, this foolish war. Folks could just look at it. That would be good. I’m thinking comedy is going to help a lot. There’s going to be Palestinian and Israeli comedy groups that walk the streets and have vests that blow up into flowers that try to say something comic about all this.

That wonderful Palestinian girl who put on her bombs and everything and walked into the pizza parlor and decided she didn’t want to do it. She decided she’d just as well have pizza with these folks. She’s one of the heroes, but we’ve got her in prison. She should be “Minister of Tourism” for Israel.

Guernica: How might he [Rumi] respond to the many kinds of religious fundamentalism which are rampant all over the world?

Coleman Barks: He didn’t like there to be religious boundaries. He said if you think there’s an important difference between being a Christian or a Jew or a Hindu or a Muslim or a Buddhist, then you’re making a division between your heart, what you love with, and the way you act in the world. That was such a wild and extreme thing to say in the 13th century with the Crusades coming across that peninsula. It’s pretty wild to say even now.

We’re all the same species. We all have children. We fall in love. We all have an impulse to praise and to worship. He says it’s all “thing,” it’s all one song that we’re singing. I think Joe Campbell would say that too.

Rumi would try to coax [fundamentalists] away from their identifications or, at least, make them more compassionate. He says that all of the wars and conflicts we have are all about names. It’s such a foolish thing to argue about names, when what we’re doing is all one thing. He says—it’s a beautiful image, it’s sort of a Christian image—that we can quit this argument because there’s a table that’s been set, and it’s waiting for us to come and sit down. That’s what he would do, he’d say, “Let’s serve some food.”

To comment on this piece: editors@guernicamag.com