By Manash Bhattacharjee

The legendary births of Christ and Krishna were preceded by the mutilation of children. About the former, José Saramago wrote that we do not need a prophet if it costs us the slaughter of children. But there is also something prophetic in the nature of this slaughter: Herod ordered the execution of all young male children in the vicinity of Bethlehem to avoid the loss of his throne to a newborn King of the Jews, and Kamsa (Krishna’s uncle) went on a killing spree after hearing that his sister’s eighth child would kill him and usurp his throne. These stories illustrate how divine prophecy simultaneously instills a child with prophetic power and puts him at risk vis-à-vis the power against whom the prophecy is directed. Legendary discourse has been exposing children to the dangers of mutilation since time immemorial.

To shift the frame from ancient myth to modern historical time, we can look at Pablo Neruda’s poem, ‘I’m Explaining a Few Things’ about the Spanish Civil War. His description of children’s blood in the poem, with its emphatic repetition, is memorably chilling:

and the blood of children ran through the streets

without fuss, like children’s blood.

Children’s blood is not mature enough, not old enough, to protest. Children’s blood is un-protesting. Children deserve absolute empathy because even though represented by political discourse, they are not political (yet). But does that make them prey to religious discourse? Do we confer an overwhelming spirituality on children? They are a bit like animals, still not fully inducted into the humanising machine. It is our distance from them that overwhelms us, of that lost kingdom of pre-humanised cruelty and bliss. Children are cruel too, but outside the discourse of humanist reason. Are children prophetically cruel? A dangerous thought, worth asking and thinking about. Thinking trembles at this moment, because to grant children their prophetic quality is to open them up to the risk, to the danger, of mutilation.

The children of other religions have been historically seen as potential threats to the faith.

Earlier, children who were perceived to be the threatening prophet of change were considered too dangerous to live. That is how Herod and Kamsa saw the children they ordered for mutilation. Along with the successful birth of the divinity (Krishna) and the prophet (Christ) however, was also born the idea of the evil child. In the Gospel of John, it is clearly delineated, under the yardstick of “righteousness,” who the children of god are and who, the children of the devil. In modern day horror films (including narratives of figures like Hitler), we find the cinematic personification of this Christian representation of the child as evil. Ruled by the devil, the child would be shown to display a propensity for killing members of his family and others around him. In this manner the prominent idea of the (devil) child persists in its legitimacy.

Along with the discourse within religion of the unrighteous or dangerous child, the children of other religions have been historically seen as potential threats to the faith. This prevalent psychology of fear and suspicion, apart from the zeal to coercively spread one’s faith, made children undergo either persecution or get co-opted through religio-juridical means in the form of conversion. The mode of forced conversion acted as a way of quelling free violence. During the Inquisition, children of Jews and other heretics were forcibly baptized. The Ottoman Empire institutionalized forced conversion of Christian children. In India, Muslim and Portuguese rulers, followed by Christian missionaries, have indulged in converting children of heathens along with the adults. Under the historico-political reasons of domination and control lay the underlying discourse of painting the child of the other in evil terms. The problem has persisted in modern times of perceiving the heretical child of one’s own or another religion as devil incarnate. Through a profound twist of irony possible in secular modernity, the prophetic child (someone out to radically reform his/her faith), may also be depicted as the child of the devil. Salman Rushdie’s representation as the son of the devil, post the publication of The Satanic Verses, is a case in point. Articles titled ‘The Devil Made Him Do It’ and ‘Return of the Devil’s Son’ were written about him. Rushdie became the satanic child of a satanic book. The aesthetic imagination of Rushdie was seen as a proof of his devilish incarnation. Rushdie was seen as the anti-prophet, and as a Muslim himself, he became the evil within.

Children become the raw surplus of violence in such instances, where the community pays its historical price by the forced sacrificing of its children.

Today’s age of reason has further expanded the discourse of evil into other forms. Through its constructs of race, class and nation, the idea of the evil other has proliferated in every society. No wonder you find children of Muslims and Dalits being mutilated without mercy during communal riots and casteist violence in India. Or Palestinian children bearing the brunt of war in Gaza. Children become the raw surplus of violence in such instances, where the community pays its historical price by the forced sacrificing of its children. The killing of children becomes the desired mutilation of a community’s future and hence, lessening its threat as an enemy. Thus (the idea of) the child as other and hence evil has the capacity to emerge suddenly and break the jaws of reason.

Consider the ways in which we have trapped children into the discourse of the modern state. Schooling is a coarse alibi for inculcating divisive values in them. The word “training” involves, with all its Greek, Roman and Brahminical echoes, imparting education that endorses rather than questions and criticises a society’s and nation’s conservative and discriminatory loyalties. Such loyalty-producing factories turn schools into camps of learning, and children get caught within the larger perception of a society turning into a fortress of quasi-military values. The question of evil returns, this time to haunt us in the form of secular laws. Modern constructs of rationality have in no way been able to rid us of old, religious perceptions of evil. Rather, they have merely managed to create new forms of threat-perception through the justificatory discourses of militant nationalism. Children end up being victims of these pathological constructs.

The child, suffering the burdensome representations of divinity and evil, needs to breathe freely before being claimed by the ruthless laws of this world gone morally haywire.

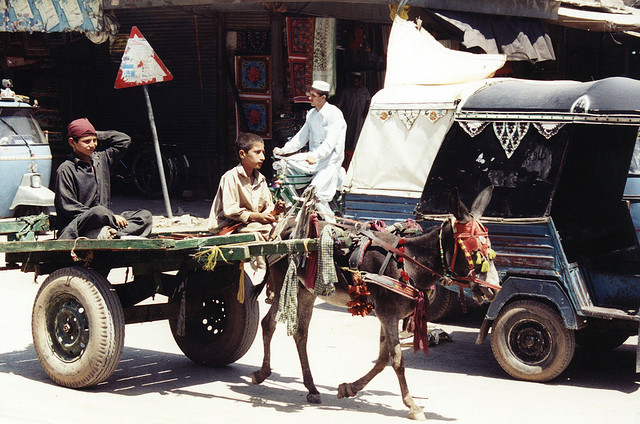

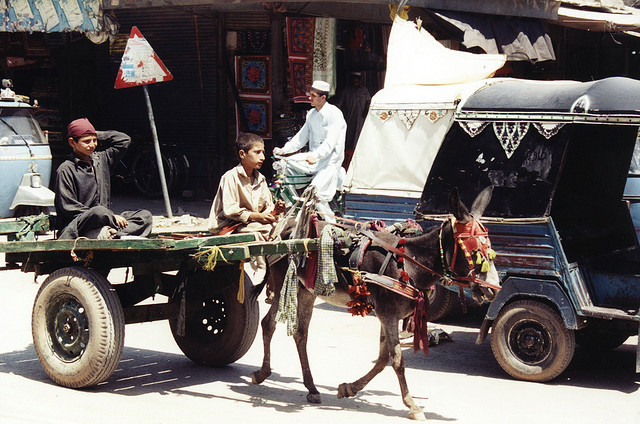

Let us pause over the latest massacre of children in Peshawar. Was the Taliban’s attack on the army’s children in Peshawar in the realm of ‘mythic’ violence or ‘divine’ violence? These are Walter Benjamin’s terms: ‘Mythic violence’ spills blood and restores law/power, such as national liberation struggles ending with the formation of the nation-state. ‘Divine violence’ (considered “pure”) is, in contrast, bloodless, involves a sacrifice untainted by any form of guilt, abolishes law/power and restores justice. The possibility of such violence in modern history came close during Robespierre’s and Lenin’s takeover of the French and Soviet state respectively, but in both cases the legitimizing violence of the state took over, thus nullifying its revolutionary potential. For Benjamin, divine violence was best articulated by workers’ strikes, which also holds true in our times. Returning to our question, the Taliban’s act, in the context of massacring children, was at best an unholy mix, where ‘mythic’ violence unleashed its virulence in the garb of ‘divine’ violence. The Taliban assaulted the institution of modern national law (that in Pakistan’s case is partly religious and partly secular-democratic), being themselves a violent institution of a religious law-unto-itself. And their idea of justice is a revengeful, blood-spilling self-sacrifice, thus seemingly outside the realm of guilt. But this is not at all the case. The Taliban’s act is retributive violence most brutally tainted by revenge. That makes it an unjust and anti-revolutionary violence; a punitive barbarism.

Children have to be rescued from wars in the name of divinity and evil, and from the quarrels between evil and reason. Their blood cannot feed the wrath and bigotry of convoluted adults. Children need a future without the shadows of death. The child, suffering the burdensome representations of divinity and evil, needs to breathe its prophetic childhood freely before being claimed by the ruthless laws of this world gone morally haywire. Let children be.