On Saturday, June 30, Egypt’s first civilian president Mohamed Morsi stood tall among over twenty military leaders, his black suit stark against the sea of khaki. A year before he was a minor figure in Egypt and unknown abroad. The military base where they were standing, known as Hike Step (or Hikesteb, as Arabic has no ‘P’) was not well known either, due to the secrecy of Egypt’s army.

Pundits ignored the public spectacle, focusing instead on whether Morsi would have any real power. Several generals had recently said on television that they would exercise “very limited” legislative authority, though just weeks before they had been accused of orchestrating the dissolution of the country’s legislature. The generals will also oversee the budget for the time being, and likely control the military budget long after. They might also appoint the assembly that will write the country’s constitution.

Egyptians alternated between seeing these officials as masterminds of intrigue and as bumbling old men, stuck in their self-congratulation over victories long forgotten by their people.

Surrounded by empty desert, squads of soldiers stood in single-color blocks. A band played the national anthem. Soldiers fired tanks and guns, and jets thundered overhead. TV crews trained their cameras on five American-made Chinook helicopters circling above the action. One helicopter held an Egyptian flag that was falling apart. Some were outraged that a tattered flag would be used for such an occasion; others claimed on social networks that this was the flag that had flown on the Western Bank of the Suez Canal on October 6, 1973.

While I was living in Egypt last year, references to 1973 often peppered conversations about the country’s military leaders. Egyptians alternated between seeing these officials as masterminds of intrigue and as bumbling old men, stuck in their self-congratulation over victories long forgotten by their people.

October 6, 1973 is the date that validates the military’s overbearing role in public life, when a surprise attack on Israel during the holidays of Yom Kippur and Ramadan turned Egypt back into a formidable regional power. Egypt had lost the Sinai peninsula to Israel in 1967, and on October 6 Egypt crossed the Suez Canal to reclaim their lost territory. On the 2011 anniversary of October 6, Mohamed Tantawi, head of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), drew a connection between those events and the contemporary revolutionary youth movement. “The youth of this generation,” he announced, “are an extension of the youth of the October generation, who proved competent in shouldering the national responsibility, and achieved victory through offering ultimate sacrifices.”

But those same young people openly mocked his pageantry. His comparisons to 1973 reminded them of the speeches of his former boss, Hosni Mubarak. “SCAF is going to pull out all the stops as it pushes more Oct. 6 propaganda to make dissent socially unacceptable in Egypt,” quipped Firas Al-Atraqchi, a journalism professor and well-known editor, on Twitter.

Spurred by these kinds of comments, I wanted to get a better understanding of the meaning that this date holds in Egyptian culture and politics. I decided to visit the biggest public memorial to their biggest victory, the Sixth of October War Panorama.

It took three attempts for me to visit the Sixth of October War Panorama, about an hour in traffic from my apartment in Cairo, before I was actually able to get a ticket. It was Kafka tourism. I had read in a guidebook that the museum remained open until 9 p.m. and I verified this information by phone. The first time, I arrived at 6 p.m., and a man sitting at the ticket window told me the museum was open from 11 a.m. until 5 p.m. A month later, I returned at 3pm one Sunday. “I’m sorry,” a different man told me, seeing that I could notice some families milling about inside. “We open at 9 and close at 2. You must come back.” Several weeks later, I arrived at noon. The man behind the counter made me wait until 5 p.m., but finally handed me a ticket.

As we entered, stage lights went up to the sounds of thundering drums and bombastic trombones, strings flickering like air raid sirens and cymbal crashes mimicking the Suez Canal’s waves. Sound effects of recorded gunshots, shouts, and explosions brought the battle scene to life.

The IMAX-sized walls display a socialist-realist rendering of glamorized war: plumes of smoke, tanks rolling perilously near cliffs, fires and barbed wire and shrubs and tires and bullet shells and abandoned, bloody uniforms. The seating area in the middle of the 360-degree image turns slowly, and your eyes adjust to realize that in front of the painting sits a three-dimensional diorama seamlessly connecting your seat to the painted background through a strewn foreground. Mortars look a little dusty but still ready to fire and there’s a tattered Israeli flag, stitched from a picture rather than obtained from the source, though I suppose that is not surprising.

The panorama is not Egypt’s only ode to the 6th of October. There is a 6th of October bridge, a 6th of October road, and a 6th of October city, a Cairene satellite city hosting half a million people in spacious subdivisions that evoke suburban America.

After having lost several wars and, in 1967, losing the Sinai peninsula to Israel, Egypt attacked by surprise on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. After three days, the Israelis fought back. Threading their way through a seam between two Egyptian clusters of troops, they crossed the Suez Canal and pushed the Egyptians less than 70 miles from Cairo. The UN brokered a ceasefire. The U.S. and the Soviet Union negotiated the terms in a rare bit of Cold War collaboration, and the fighting ended.

Israelis, although they won, no longer saw themselves as invincible. Egyptians, although they lost, no longer saw themselves as weak and defenseless. This made both sides more amenable to talks that resulted in the Camp David Accords six years later. Sadat became, as he is still titled on many statues throughout Egypt, the “hero of war and peace.”

After 1973, Israeli scholar Yoram Meital argues, “more and more war-related symbols were internalized in [Egyptian] public life. Evidence of that was present in street signs, formal declarations, schoolbooks, and even advertisements.” When Mubarak came to power in the wake of Sadat’s assassination, he emphasized his own role as air force commander. At that time, all of Egypt’s leaders since the 1952 revolution had been members of the military. They still wore their uniforms in public. Sadat’s death suggested imminent chaos, so Mubarak played up his military credentials in order to present an image of himself as the nation’s protector.

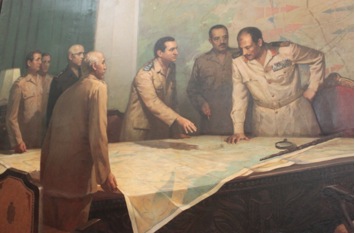

If aspects of the message portrayed by the panorama are muddled or dated, it was impossible to deny the clarity of one mosaic, which looks over visitors as they exit. It depicts a meeting between army commanders in a conference room. The walls and a large table are covered with maps of the Suez Canal region and a magnifying glass sits to the side. A group of commanders are watching Air Force commander Mubarak, his hand outstretched to indicate a point on the map, explaining his plan for battle to President Anwar El-Sadat, who solemnly listens to his successor.

Most accounts of the Panorama by American visitors note the total absence of Israeli counterattacks with high snark and rolling of eyes, seeing it as pure revisionism. Upper-class Egyptians have told me that they “cringe” every time they pass by the building, because they feel Mubarak used this garish kitsch to paper over the country’s steady economic and social decline.

***

On a chilly Sunday in February, I visited a different war museum, in Port Said, where the Suez Canal meets the Mediterranean and greets the world’s tankers and tourist ships. This city is more famous for a different narrative of Egyptian pride, in which the townspeople had kicked out the British-led invasion in 1956. I met Muhammed, a young soldier whose post for the year of compulsory military service is to work as a tour guide.

He took me to the 1973 room. On one wall, I spotted a mural like the one at the Panorama, portraying the same meeting between army commanders in a grand conference room, the same walls and table are covered with maps of the Suez Canal, the same magnifying glass resting discreetly.

Sadat bows his head to Mubarak with the same silent respect, but it’s not the same picture. The other commanders are different men, with different positions and clothes and expressions. One of them, upon closer inspection, looks suspiciously like Mubarak, meaning that the future president is watching the future president in his moment of glory.

“Do you see that?” Muhamad asked, a bit giddy, “There are two Mubaraks! He was so in love with his own glory that he had to put himself in the picture twice!”

“Mubarak was not even at that meeting,” he continued. “He put himself into the picture to make us think he was a hero. We have been talking about replacing this painting with a correct one, without Mubarak, and certainly without two Mubaraks.”

At this point, the generational divide, evident in the camp of the panorama and the snark of liberal young Egyptians, has widened beyond bridging.

He paused and reconsidered. “But maybe we’ll leave it in place, as a memorial to how out of touch this regime was.”

***

Although the military council technically handed over authority to Morsi on Saturday, June 30, it was a pageant on the military’s terms, in the same faded glory of 1973 vintage, that will likely take Morsi years to update. At this point, the generational divide, evident in the camp of the panorama and the snark of liberal young Egyptians, has widened beyond bridging. These young activists see a cabal of old men celebrating a historically distant victory over Israel, which now represents the least of Egypt’s current threats. They see a continuation of the Mubarak regime and its use of empty military kitsch to authorize dictatorial rule. The SCAF, on the other hand, see the activists—and likely Morsi, the Islamists, the liberals, the popular classes, the NGOs, the private sector economic elite, and pretty much everyone else in Egypt—as ungrateful and incapable of keeping Egypt safe from foreign domination the way that they, the real saviors of the nation, did back in 1973.

I understood this intellectually. But it was not until I visited the October War Panorama that I felt it viscerally: the pride of improbable victory, of protecting a homeland from external threat, of reversing years of weakness at the hands of imperial aggression. It was true that the October generation produced a story of national dignity that could be told again and again—and it’s also true that the story now resonates less and less. Like Egypt’s military establishment, the panorama has fallen into grand, dramatic decline. Whatever else the 2011 revolution did, it created the roots of a new narrative for young Egyptians.