She tucked the corners of her face in and went back out into the world, knowing the red and blue trail her guts were leaving in the street behind her would repulse at least some people.

Eerily, the standout blue veins in her neck and at her temples made her look vaguely like an aerial map of Siberia. Even though in this place she knew the word “Siberia” did not signify, somehow she took comfort in how Siberian her neck and temple veins looked and walked with a slightly straighter spine, though she noticed people she passed by looked at her with disaffected latte pity. But to her she made a lot of sense. Her mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother had been Lithuanian, had survived winters, had been sold to Russians, had died in white and cold and poverty, and so a vast white expanse with rivulets of black and blue was a concept she understood. Didn’t land look that way to birds on great journeys? Birds had outlived the ice age. Perhaps my body is like a map of a place seen from the sky. She looked up. Then she returned her gaze to the faces of the pretend pretty American city.

Yes, she had a vague understanding regarding the fact that her insides were visible on the outside, and how not the custom that appeared. But what were exposed capillaries and gut entrails dangling from a girl’s midsection compared to the fat wallets of billionaire businessmen jutting out from the asses of their fine suits, or the violently painted lips of women with hairstyles and manicures rivaling the price of apartments?

She looked up. Gray sky, gray of buildings. Cement with wind. At least there are trees. Trees never lie. But where in the world, she wondered, were the graywolves?

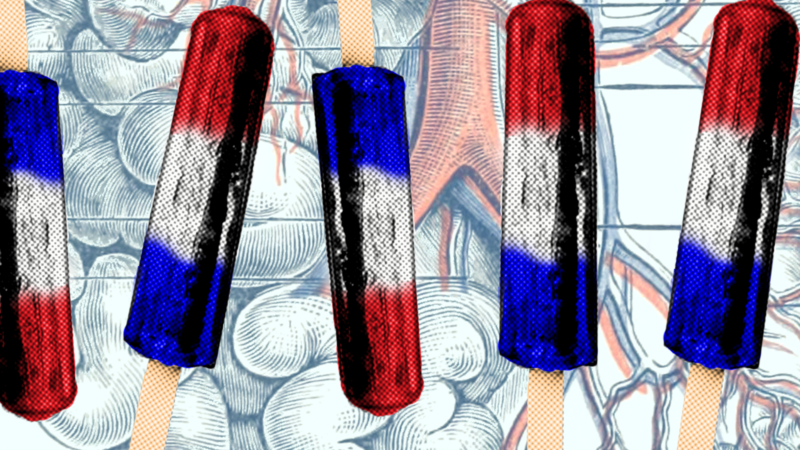

Pulsing outward, she made her way to the “front man” whose address she’d been given when she arrived through Canada in a popsicle truck painted entirely white. Girls like popsicles driving over stitched borders between nations. Apparently, this kind of “front man” did not regard an inside-out girl as unusual or damaged. She still had her “use value” in this place, is what she understood the man on the phone to mean when he said, “Are you at least a C cup?” Her heart hidden behind the pillows of her adolescence.

The “front man” lived near a freeway. But she did not feel its freedom.

The “front man” lived in a snot-colored two-story house with black plastic in the windows where curtains should be. When she knocked on the door of the “front man” her throat chords braided and her vertebrae clattered briefly. The man who answered the door looked to be in his late teens. Older than her. Inside were more girl popsicles around twelve or thirteen. One seemed perhaps to be fourteen, but tallness wasn’t necessarily a sign of age. Two seemed to be young enough to need mothers. She stared at the melting popsicles. All the popsicles had too-thin too-white wrists with bulging blue rivulets winding around them. But the television in the living room bombarded sensory perception with image and sound and waves. She bit down on her tongue enough to feel it.

Good blood in a mouth.

Days went by.

Enough to create time.

She ate.

Slept.

And in the evenings, every evening, she was “delivered” to some new address.

Each address had an old gray man billionaire with money enough for a girl’s body and threat enough to take her life.

The pretend pretty of the Portland city all around her days: disposable cartons and plastic and paper and coffeecoffeecoffee and black clothes and bike lanes and funny little hats and eating and driving and thousands of varieties of potato chips. Whole aisles at grocery stores devoted to potato chips. Salty chips and square ones and greenblueyellowred ones. Chips with pepper and chips with vinegar and chips with lime and some with “bar-b-q” flavor, reddened with dye. Coffee spilling from the mouths of hundreds of shops and beerbeerbeer everywhere and strip clubs outnumbering McDonald’s. Had the regular well-dressed and coiffed people walking around like Bic lighters frequented as many strip clubs as she had? Did they form attachments to other mammals? Her emotional circuitry endlessly interrupted every time she took off her clothes.

Of the land in the Portland, there were mountains, reminding her that terrain could still overtake puny humans, but she couldn’t hear their stories from where she was, boxed.

She saw the lively mouths and freshly sculpted bodies and the surface sheen-being of the people in this place, she saw their righteous bicycling circles and the corners dominated by coffeecoffeecoffee, she continually bore witness to the couplings of pretty people and the neon signage and the stutter of bridges over incarcerated rivers. Still, even walking the sidewalks smelling the pee and rotting food mixed with just-made food-cart food and car exhaust and wet leaves and dirt she could see that money and consumption were what the place was made of. Why was everyone pretending self-worth? How did they wear their “I’s” so easily?

Sometimes while walking she witnessed animal behavior, such as blue jays adopting different languages, or garden snakes S-gliding over cement into shrub havens. Or the cacophony of frogs under overpasses near streams or gutters. Walking nowhere reflected her a sense of nonbeing she could live with. However, sometimes she felt the possibility of a bone spur in her left heel. Sometimes she stopped. Sat in the dirt. An old beer can might tumble and blow by her. “Coors,” it said.

She considered trying to speak to other mammals. But her voice locked in her throat when she thought about being a girl with nothing, not even a family, no money, a name without “documents,” and then all she could feel was the warm caved between her legs and the small and sure soft swell of each of her breasts and so she thought, Well, at least my body has meaning. Even if my insides are coming out.

In the evenings when she was “delivered,” as with cardboard boxes from UPS trucks, or as recycling to the side of the garbage where big green rubber-gloved hands sift through a thing, or as flowers that lose scent before their meaning travels, she went dead.

Her always every night destinations threatened to unweave her intestines and pour them out in a gray mucous line onto the street. Somewhere in her skull or rib cage was the hint of a memory. The word “family.” The word “home.” But the memory hints were not present enough to negate their absence in this place. In this place, it was be or die. In this place being was her bodyworth.

This night like every other night the doorway to the establishment looked to her like a droopy yawning mouth on a sickened old man with no teeth who’d lost the turgidity in his skin. Repetition makes something real, is what overtook other truths in this place. Just look at commercials. Brands. Memes.

Her eyeballs shivered and her rib cage made a sound in the wind a little bit like obsidian wind chimes. Knocking on the door took a lot more than a girl.

Well, she thought to herself, even if I am entering the loose-skinned mouth of a saggy old man, “a job’s a job.” A phrase she’d taken in from the mouths of other popsicles as a personal survival mantra. Because do not do not do not behave like an “immigrant.” Language is a funny thing, she thought. It opens and closes. It trips you like a crack in the sidewalk. Keep moving or die.

On the television in the hotel bedroom of the slackened old gray man—her “john” for the evening—was a war zone. Just between the old gray john man’s legs spread over her face she could see the televised bombed-out rubble, the huddled clumps of human crouched and lurching and running, as the old man john shoved his leathered velveteen sag balls into her mouth. “Suck,” he said. Deflated bad-tasting balloons filled the cavern of her mouth. The rubble and the humans and the CNN ticker tape telling something… what was it… news… she closed her eyes and sucked. He fingered into her. He put his jowls down near her face, his mouth to her ear, “I’m going to be a very important man someday… THE MOST IMPORTANT man…” “Your little holes are so tight,” the old gray john said, smiling wide enough for her to see decreasing pink of his receding gums. Her little holes.

Always upon her return to the cement house of the “front man” she would relate the one thing she owned—a story in a foreign tongue—to the other popsicles. She did not know why she related it, she only knew the enunciation could not be stopped. What else did she have? What currency but story? Like the continual expulsion of her insides longing to reside on the outside of her body, like screaming entrails, story came. And the popsicles would lean in, eyes wide, mouths open, wrists open to the future when she told.

Long ago in a faraway land, there was a tsar who had a magnificent orchard, second to none. However, every night a firebird would swoop down on the tsar’s best apple tree and fly away with a few golden apples. The tsar ordered each of his three sons to catch that firebird alive and bring it to him.

The two elder brothers fell asleep while watching. The youngest son, Ivan, saw the firebird and grabbed it by the tail, but the bird managed to wriggle out of Ivan’s grasp, leaving him only a bright red tail feather.

Ivan, assisted by a graywolf who’d killed his horse and then felt sorry for him, because even wolves understand how unfortunate men are, managed to get not only the firebird but also a wonderful horse and a princess named Elena the Fair. When they came to the border of Ivan’s father’s kingdom Ivan and Elena stopped to rest. While they were sleeping, Ivan’s two older brothers, returning from their unsuccessful quest, came across the two and killed Ivan, threatening Elena to do the same to her if she told what had happened. They ravaged Elena and threatened to cut out her tongue.

Ivan lay dead for thirty days until the graywolf revived him with water of death and water of life. Ivan came to his home palace at the wedding day of Elena the Fair and Ivan’s brother. The tsar asked for an explanation and Elena, with the wolf standing guard gnashing his teeth, told him the truth. The tsar was furious and threw the elder brothers into prison. The wolf ate their entrails out in the night. Ivan and Elena the Fair married, inherited the kingdom, and lived happily ever after.

None of the popsicles ever commented on her story. But the story brought sleep like a kind night ritual, and sleep lapped over them.

Time passed.

Enough time for her to realize no graywolves would come.

Although she knew that stories had beginnings, middles, and ends, she also knew that for “immigrants,” the order was out of whack. Once there was a story but that story had been fragmented and gnawed at the edges. Once there were heroes and saviors but they had turned into con artists and reality TV and the dizzy whir of consumers. Or maybe there were never heroes and saviors or just the stories of heroes and saviors to trick girls into forgetting how to be animals.

Strength in a girl from Eastern Europe lengthens spines, so that the beauty of their necks and backs looks to be as a fine cello. Strength in a girl like her made her eyes smaller and more steely blue, her jaw more square, her cheekbones high and angled clam shells. Even her collarbone spoke, but in this place people only responded with dead stares or shrugged shoulders.

You haven’t enough English, they said.

Wait, can’t you hear my collarbone screaming? Where were the graywolves—the real graywolves, furred and growling and teethed—that might rip loose the entrails of enemies?

The last night, in the hours before dawn, after she had been redeposited back to the house of ravaged popsicles, after she had again told the story from her mother dead, her grandmother dead, her great-grandmother dead, after she washed the blood from her mouth, her nipples, from between her legs where she realized life would never pass the way it had moved from the cleft of her mother, her grandmother, her great-grandmother, and the blood from the smaller aperture of her ass, the rivulets of red winding their way down the rusted drain holes of an unclean shower, when she put herself down on a formless mattress on the floor under a window of the house filled with girl popsicles, the cave of her cement world opened up here and there, and through the cracks in reality or maybe the little ordinary window hole she could see the towering white-eyed angels hovering over them, “streetlights,” they called them here, and a night watch of lost leaves whispered against her hair. And tin and paper rustlings made urban lullabies. Or maybe it was just the ugly end of the city, like everyone kept saying… on television… where girls go to disappear and die, but in her lineage couldn’t death transform into animal by a lone girl? Not as an ending but as a bluewhitened pulsar, couldn’t it, blazing the entire night sky apart and atomizing everything ever done to girls? Couldn’t deranged dreamstories where graywolves came back from myths to tear out the throats and sag balls of old gray johns still enter through astral projections ancient as folktales embedded in the dead bones of her mother, her grandmother, her great-grandmother, gone to dirt but still, still, weren’t there secret triumphs to living dead girls?

There is a certain rare strength that lives only in adolescent girls. No one knows the word for it.

She punched a hole unthinkingly with her fist through a high-up window in the cinder block box of their lives. She elbowed the hole until it was big enough for the popsicles to leave, elbow blood everywhere, then quiet as a mother’s, a grandmother’s, a great-grandmother’s voice singing a child to sleep in a mothertongue they slipped out. As the popsicles tumbled out into the night like child refugees in a war-torn country—oh! how they glowed like human snowflakes underneath the streetlights!—she knew what else to do. She’d have to conjure the graywolves. Not the old gray wrong billionaire American man wolves but the real graywolves. She took the broken pieces of window glass and gutted herself so that her entrails were finally fully free and right. They slithered out in vivid shades of girl—ssssssssss onto the floor. Someone must stay behind to help the story make a dream wall.

And it was true, for only then did the real graywolves smell it—her entrails, animal and good—and they came down from the mountains one, two, three, four, ten, twenty, and they entered the cinder house and ripped the throats from the wrongheaded men and tore them limb from limb and the wolves’ teeth and the wolves’ howls reminded everyone everywhere how there is something from spine and ice that has yet to form a language, an as-yet unfinished sentence, those Eastern European girls so bought and sold are learning something besides English, they are learning to gut themselves open so that others will run.

What was left of her body combusted into fire and burned even the cinder box and bones to the ground.

I tell you, do not go near that place. Do not go near it. It is said that graywolves guard the very ground, ready to rip out your throat and entrails—your perfect language and grammar of things.