When you say you’ll take him “in sickness and in health,” you don’t think you’ll be cleaning up vomit in the airport. Even if you think cancer, you certainly don’t think he’ll forget the day you married and the day you buried his mother and the days you had children. But you’re not thinking about any of this when the skycap wheels him from the limo to the airplane that will take you across the country to your new home in California—the one you barely had a chance to move into before the surgery—where your girl is finishing school. You’re thinking how great it is to be doing something normal, out of the wretched cancer hospital, on your way to eating real food again, when you look down and see that his eyes are as wild as a frightened puppy’s.

You say, “What’s wrong?” and he can’t tell you, he has no words, and so you stop the wheelchair and come around the front. “You need to rest?” You’re asking like he’s a child, and you suddenly see, he is. His head turns from side to side, and you know that he can’t stand being among people again. You move him behind a partition, and you put three chairs together to make a bench, and you turn him toward the wall, and you cover him with a jacket, and you tell him he doesn’t have to get on the plane until the end, after the people have all gone. Still, you don’t know how you’re going to get him on board without him feeling bombarded. The first soldiers have started coming back from the Iraq War and you watch them in their camouflage gear, and you wonder if they are on their way home.

Your husband falls asleep, and after a while you wake him and you take him by the elbow and you raise him to a sitting position. He looks up. You see that the crowd milling at the gate terrifies him. You ask if he wants to go to the bathroom and there is no answer.

You say, “You can’t move yet?” and he nods his head.

Boarding announcements continue. You wait until most passengers are on the plane and you wheel him toward the toilets. He tries to stand and he wavers and you yell, “I’m coming in!” in case there are men at the urinals, and when you go in, you see a man looking at you strangely, then pityingly. Your husband stands to urinate and you turn your back and wait at the door. You listen for him to finish and then you place him back in the wheelchair. When you leave the bathroom, you strain to move him across the carpet toward the gate. All the passengers’ eyes turn toward you, and then they turn away, fast.

“No!” he says.

You turn the chair away from the gate and toward the quiet corner. You kneel in front of him. He retches.

You say, “Do you think you can get on the plane?” and he raises his shoulders and there are tears in his eyes. You say, “It’s okay, we can catch another one,” and you touch his face. You say, “We didn’t know it was going to be like this, honey.” You like to speak with assurance when things no longer seem rational.

While your husband waits, you stride to the gate and you describe your plight to the flight attendants, but you don’t tell them he is a baby suddenly. You say “chemo” and “nausea” and “just have to make it home” and they tell you they will come and get you after the people board, and before the plane takes off.

When you make it back to your husband his face is pale. He says, “I am going to throw up.”

You wheel him back to the bathroom. He raises up, vomits. You run paper towels under the cold water, wipe his face, clean the sink.

You take the ends of the blanket and you make a cave for him. You touch his forehead and you ask what it is like to defy death.

You help him into the chair and you say, “One more try.”

When you enter the corridor it is empty.

The agent says, “We’re holding the door for you.”

The flight attendants are wheeling him onto the plane then, and you discover that passengers inside have shifted so you can sit up front together. You hold on to your husband’s arms and you say, “Look down,” so he can walk to the seat. People bring you water and pillows and a blanket. After you buckle your husband in the window seat, you look at his face where the terror still swarms. You take the ends of the blanket and you make a cave for him. You hold it so he cannot see other people and soon he falls asleep. You touch his forehead and you ask what it is like to defy death. He tells you from his dreams, which you can suddenly hear.

He says he isn’t afraid of having no story. He will learn whatever past will be necessary to stay here in this place. He says death was like any other moment. He slipped away, and then he was present. There were no white lights, there were no ancestors or gurus to meet him, there was no pain. He doesn’t know if pain exists. He says he likes having a body. A body reminds him that he is fresh here. For example, when he is thirsty, he must drink. He opens his eyes. You hand him the water.

It will go on like this for a long time.

We arrive home to a three-room apartment in Laguna Canyon, a tidy, transient building with an outdoor pool and a party room that always seems to be full of off-duty strippers. Palms and pepper trees surround the sunny property. Our rooms are on the edge of the sandy hills of the Laguna Coast Wilderness Park, where there are rattlesnakes, rabbits, red-tailed hawks, and coyotes that yelp in the distance. When we first arrive from the hospital, our teenage daughter has cleaned the house and arranged flowers and stocked the pantry with nourishing foods. We’re happy for the simple things. We put away our clothing. I talk to Dylan about the homecoming dance. We go for walks in the morning fog.

Every day I expect to wake up and discover that the morphine has worn off, as the nurses promised, and that Richard is back to the man he was before the surgery. Instead, quiet. A stare. A step or two. A question repeated. I make him breakfast and I bring it to our bed. I get our daughter off to high school, clean the house, make doctors’ appointments, wrestle with insurance, write thank-you cards, open bank accounts, order film from the MRI laboratory, email other PMP caregivers we met at the hospital, take the car into the dealer, attend Dylan’s voice recitals, organize her college audition tour, consult with friends about alternative healers, fill out college financial aid applications, apply for Social Security disability, manage our finances, talk to Richard’s employers, send letters to family and friends to update them, work with people in recovery for addiction, meet with Dylan’s teachers and vocal coaches, hunt down research on the brain, organize visits from friends and family, write stories, send my work to magazines and editors and agents, plan Thanksgiving with my son and father, plan Christmas vacation with our families, take Richard to a doctor visit every week, and talk to friends and family about our new state of affairs. My calendar looks like the work of a madwoman who cannot endure a moment of silent repose.

He sleeps. He sits and falls asleep. He reads and falls asleep. Each morning, I cajole him to get out of the bedroom, to go for a walk around the parking lot, to take a dip in the pool. He does not want to leave his bed. I promise him he can come back to the apartment if he’s uncomfortable. We walk a few feet in the sunlight. I hold his arm, place my hand on the middle of his back so he can sense his own body. He tucks his head, unable to take in the bustle of daily life, the noise, the movement, the aromas, the intentness of everyone around him. Every day I push him to go farther. My voice is gentle, and inside, I’m terrified. What if he doesn’t come out of this infant state? How will we live then?

After we return from the hospital, we start to sort out what happened in there. The cancer center had its own laws and dogmas and edicts. Being home at least allows us to live by our desires. There is good, organic, beautifully cooked food. There are walks in nature. We have our daughter getting ready for college. We are in contact with our son, who is attending to his college education back in Seattle. A couple of hours up the Pacific Coast Highway, I have writer friends I can talk with every week.

It’s an itch under the skin, an unease that keeps me feeling uprooted, a desire to find the correct answer when there isn’t one.

I wake up at six most mornings so I can make Dylan’s lunch and get to a twelve-step meeting by seven. Richard is awake by the time I return, and I’ll make him breakfast, coax him to step outside for a few moments, and take him to his doctors’ appointments. He’ll sleep much of the day, his body recovering from the two surgeries, chemotherapy, and forty pounds of weight loss. He’s a rail, with huge sunken eyes. I had planned to learn more about screenwriting during this time, make some contacts. Instead I’m researching online and interviewing medical professionals, trying to understand what happened to his memory.

When the brain loses oxygen, it’s said to have experienced an anoxic insult: not an insult in the sense of a demeaning or offensive remark, but rather a trauma, from insilire, “to leap upon one.” What leapt upon him, what leapt upon us who knew him, was the disintegration of his personality: the loss of traits, gestures, and expressions that burnish the behavioral patina one has grown to know. Following his anoxic insult, when people ask how I feel, I answer, “Uncomfortable.” It’s an itch under the skin, an unease that keeps me feeling uprooted, a desire to find the correct answer when there isn’t one.

The lost part of him that our family most misses is his enthusiastic desire to communicate. Without the craving to converse, there’s little self-reference, self-regard. No need to impress anyone. He has no wish to have his self reflected back in word or deed. The charm he lived by and wooed by is erased. Now that we are in this transition house, I have no idea if he will be able to work again. I know that it’s too soon to tell, and I also know that something has seriously changed in him.

The first Monday, two days after we arrive home, Richard is examined by his new general practitioner, Dr. V, who will become our advocate for all his future care. She sets up a baseline MRI the next day, and answers my questions about the memory loss. We learn about the stagnant anoxia that results when internal conditions block oxygen-rich blood from reaching the brain. Brain injury specialists say that the death of brain cells results in the interruption of electrochemical impulses and in interference with the performance of neurotransmitters—the chemical messengers that transmit messages within the brain. The neurotransmitters regulate body functions and influence behavior. We need to get someone to clarify if he has had an anoxic insult, Dr. V advises, and to what extent he has been debilitated, and what his prognosis might be.

That autumn day we leave Dr. V’s office with a referral for a neurologist and a speech therapist. Tracking down the cause of Richard’s mental condition feels useful. People have been frank about what scientific information is or is not available, and quick to admit the limitations of their knowledge. I’m thankful that the operating surgeon, Dr. M, had the integrity to share his opinion openly. Because of this I’m able to argue for my husband’s case, and to spend our savings on getting him the best care we can while we wait for the insurance approvals to arrive.

Before we left the hospital, Dr. M handed me suture scissors. He demonstrated on Richard’s chest-tube stitches how I might remove the fifty knots that climbed from my husband’s pubis to his xiphoid. In the past month, I’d already massaged blood clots that lurked in transparent plastic tubes, threatening to ascend to his lungs and choke him. I’d cleaned up urine that overflowed buckets when night nurses failed in their duty. I’d used tiny scissors to cut his long hair when it became greasy and matted from weeks when he wasn’t able to shower. A few dozen stitches do not scare me.

A week after we come home, the fated day arrives. I tease each stitch from the skin with tweezers. The tip of the suture scissor slides under each knot and clips it. Richard watches for a few moments and then closes his eyes. He sleeps. The sun from the desert hills slides across my back. I hear my breath, panting, and his, slow and steady. I think of the two-foot-long seam splitting, his insides coming apart, red, red blood seeping over the white blanket on our bed. My hands shake. Now that I am without the hospital professionals, I imagine the disaster that I could cause through my mistakes. I track backward through time, sourcing this sense of responsibility. I cannot find a time when I didn’t think I can fuck this up.

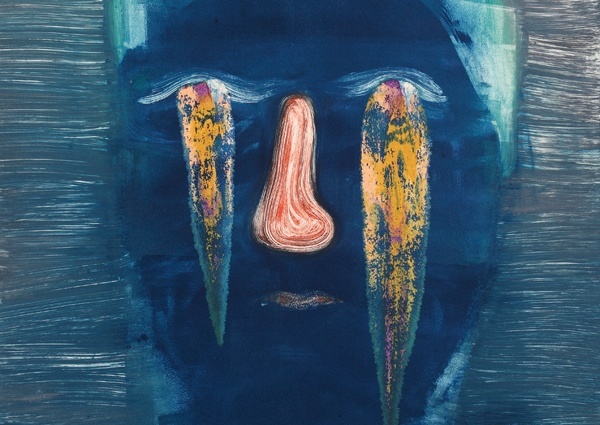

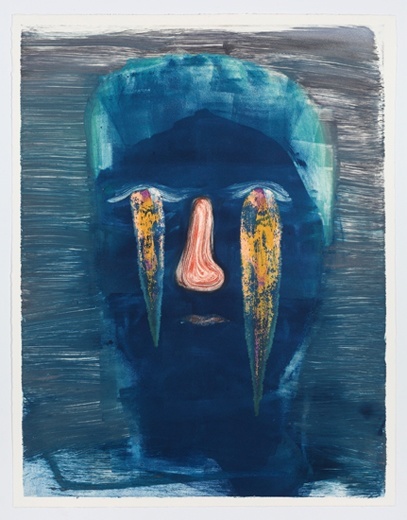

Richard opens his eyes. Since the surgery, they bulge wide, a stare without a blink. My fear of making mistakes turns into resentment that seeps toward him. Viscous, silent seeping.

“Eyes,” I say. This is our new code word to let him know that his flat affect, the fixed stare of the brain-injured, is becoming uncomfortable for others. He blinks. I tug at a stitch and watch him wince. Tears come to both of us. Catholic-girl guilt. Guilt that my mother suffered from some unnamed malaise I couldn’t fix. Guilt from my decade of binge-drinking and blackouts that I’d halted just in time for Richard to find his cancer. Not yet, but soon, I will discover that cancer has changed the game on my anger. When there’s no one to volley anger back, cementing marital guilt in its pathetic, pitiful story, that’s the end of that sorry party.

When we are finished I take the stitches outside and I bury them in the earth, along with a toy soldier I find on the patio. I kick the dust with my toes. In the distance, coyotes scream.

Being without identity is a terrifying thing. Or so it seems to me, watching Richard in those first months. He’s cut off from his memories, cut off from his preferences, cut off from his beliefs. I’m not sure if he’ll regain any desire at all. He’s lost not only his own sense of self but the one we share, our marriage history, our familial ties, our community connection, our political and social selves. Day to day, he can’t remember what makes me “me,” what makes us “us.” And that doesn’t stop him from wanting our pleasure and ease back.

In our marriage, he was my wild man, my field guide. I want a rich and complex intimacy again. Instead there is innocence and spaciousness. Sweet as he is, we seem shattered.

Two weeks after we return home, we visit a new neurologist, a woman this time. She shows us an MRI of his brain.

“No definite acute intracranial abnormality. No evidence of lesions or infarctions or hemorrhage.” The only indication: “An increased signal in the posterior limbs of the internal capsules bilaterally, slightly greater on the left…suggesting chronic ischemic change.”

Brain cells begin to die after just four minutes without oxygen. Perhaps Richard’s brain injury was a side effect of the three pitchers of blood that pooled in his abdomen while he was in the ICU.

Brain research in the twenty-first century provides more clues than ever about the way our minds function, behave, relate, relay, imagine, interpret, explore, examine, detect, and understand. Severe brain injuries—ones that manifest in comas, with no voluntary activities, no cognitive response—are easily detectable, both physically and in the person’s behavior. Mild to moderate brain injuries are often not physically detected, though they can create the kinds of deficits that seriously affect the person’s life, work, and relationships. It’s difficult to find “hard” proof of tissue damage or chemical malfunctioning in subtle brain injuries because brains are the most variable of all of the human organs. We don’t know what a normal mind looks like. (This is not a metaphor, or a joke.)

We have obtained enough confirmation from medical professionals to know that Richard is likely suffering from the effects of a hypoxic anoxic insult. This is the kind of brain injury that occurs when blood flow is interrupted, starving the brain. From Dr. M, his surgeon, to the neurologist, to the general practitioner, there’s a consensus that a loss of oxygen to the brain during internal bleeding, even if it was small, likely caused the injury. I wonder if the hospital’s delay in noticing and responding to the internal bleeding was a significant contributor. Brain cells begin to die after just four minutes without oxygen. Perhaps Richard’s brain injury was a side effect of the three pitchers of blood that pooled in his abdomen while he was in the ICU. But none of our effort will go to assigning responsibility. Right now, all we want is for him to regain his capabilities.

An injured brain is not less smart than it was before. Richard processes information more slowly, giving the impression of a diminished intellect. But that brilliant mind of his is still vital, wise, dazzling. I believe that his intelligence is simply locked inside. In my view, my husband does not have access to the use of his brilliance.

“He can’t speak; he was altered during surgery,” I say to the neurologist. “We need to find out what’s happening with his speech.”

The neurologist confirms the need for a speech therapist. Ten days later, after we get approval from our insurance company, he has his first appointment. For two months, I will drive him there three times each week.

“Name animals that start with C,” she says.

Richard looks up at me with big eyes.

“Eyes,” I say, reminding him to soften his gaze.

His eyes fill with tears. He can’t find one example.

I want to say, “Camel! Cat! Caterpillar! Cougar! Canary!” Instead I place my hand on his shoulder. I look at the therapist.

“Now what?” I say.

By the end of the first month at home, Richard gets dizzy when he stands up. One afternoon Dylan and I return from the grocery to find that he has passed out on the floor and pulled a twenty-pound sculpture of a mother and child onto himself as he reached out to break his fall.

I call Dr. V, who asks us to bring him in right away. Dr. V sends a note to the neurologist noting “short-term memory loss and difficulty with directions and spatial orientation.” We take Richard off salt, check his iron. Perhaps, we think, this is a low blood pressure issue. In six months we will learn that balance issues are common in brain injury, and that 65 percent of people with a brain injury suffer from dizziness and disequilibrium at some point in their recovery. At this time, we know only that we cannot leave Richard alone. If I have to go to a school event for Dylan, we bring someone in to stay with him. Richard resists, but he keeps getting dizzy, and he learns that he needs to have someone present until his body stabilizes. My husband is like a child—sweet, tender, toddling, and terrified to leave the house, spending most of each day napping.

He’s injured and he’s also somewhere else. To me, he’s another man.

I watch Richard’s wide eyes as he tries to understand the world around him. On our daily walks, he stumbles because of weakness in his entire right side. Although the neurologist can’t confirm the location of the injury, I remain convinced it’s in his left temporal lobe because his right side is hunched like the maimed wing of a bird.

As I observe him, I wonder if he’s managed to reach one of those states that people meditate for years to achieve. He’s injured and he’s also somewhere else. It appears as if his former self has died, and he awoke in a new life. To me, he’s another man. But Richard didn’t awaken like those people who have spontaneous spiritual events. He isn’t the Buddha, or Byron Katie, or Jill Bolte Taylor. Yet he isn’t unlike them either. Richard has no context for creating meaning. He can’t recall what happened to him yesterday or a year ago. He can’t explain recent events to anyone, not even to himself. His only motivation is love. As far as I can tell.

“Why did you come back to this body?” I finally ask him weeks after the surgery, after he’s gained ten pounds, after he’s stopped fainting, after he can walk more than a few steps, after he can form sentences.

“I wanted to be with you. It didn’t feel like I was finished,” he says.

Excerpted from Wondering Who You Are by Sonya Lea, to be published by Tin House July 2015. Copyright (c) 2015 by Sonya Lea.