Ren Hang would have turned thirty in March had he not taken his life in February. Besides the dynamic body of photographic work he is most known for, Ren Hang also leaves behind ten years’ worth of poetry and an online diary of his struggle with manic depression. The first entry was dated June 2007, and the last entry September 2016.

As many as sixty million people worldwide suffer from manic depression. On that scale, pain becomes abstract.

What is so powerful and moving in these exacting logs of the minutiae of his psychological state is to see and feel, so viscerally, that even when Ren Hang was furthest gone, he made real efforts to fight to live, to be honest with himself, to attempt to understand and contextualize his illness and his universe through the act of composition for as long as he could, even after the meaning of existence had become uncertain.

Suicide is never really a sudden sundering of the fabric of reality, although it might appear as such to others from the outside.

Understanding the acute difficulty and banal rigor of the everyday struggle with mental health demystifies the abridged, romanticized mythos of the tortured artist departed from the world too soon, and the irresistible but irresponsible glamorization of suicide in relation to artistic genius.

The unflaggingly distinct and original energy of Ren Hang’s words, poems, and photographs are an enduring testament to reckoning with the flux that is life itself: between “up on top” and “down below,” ardency and hysteria, being and nothingness, we must all fight hard to go on as best as we know how.

—Amanda Lee Koe, translator

2014.11.17

Am I a camel or a cactus? I am sitting in the middle of the sofa. The cream-colored covers are a desert. I have not felt this way in a long time. A camel with no humps, or a cactus with no thorns? I really don’t want to go out. Everyone outside is a far more decent human being than I know myself to be. I don’t want to attend any social gathering. When it is lively I fear I will be too quiet, but when it is quiet I am afraid I will scream. Just half a glass of something to drink makes me exceedingly slick, I’m so slick I might slip at any time, roll down the stairs like I’m doing aerobics or calisthenics. In moments like these nothing is more comforting than feeling the black and blue of every bruise on your body. Every mark or scar is a pill. Once pain takes the shape of a concrete form, I am no longer frightened.

Why don’t I just keep sitting here, with my back to the TV (which isn’t switched on), massaging my calves and my insteps with the remote control. Why don’t I lie down? I can spend up to 15 to 20 hours a day in bed. Sometimes I feel like I’m lying on top of the mattress, sometimes I feel like I’m lying under the mattress, other times I feel like I’m lying inside the mattress. Surrounded by a labyrinth of bedsprings, I’ll never find the way out. Getting out of bed is just as difficult as falling asleep.

I harbor the constant feeling of the door being unbolted, and I am always hearing someone ringing the doorbell. But my house doesn’t have a doorbell; I’ve never installed one. I am always hearing my cellphone vibrating. Once I took it in hand and I saw with my own eyes that it was not vibrating, but still I felt with my fingers that it was vibrating. I don’t want to pick up anyone’s calls, but the truth is that no one is calling me.

Nothing is happening, nothing has ever happened. Ardency and hysteria are merely two sides of the same coin.

2015.03.23

Yesterday at the supermarket

I stole a tube of toothpaste

The day before yesterday I jammed

The neighbor’s keyhole with a wad of gum

Last week I kicked down every single garbage can

In a row outside the neighborhood district’s gates

Each time I do a bad deed life feels beautiful again

2015.05.19

Spending the night at a friend’s house once, I couldn’t fall asleep. First I lay on the bed, then the floor. Eventually I took to sitting on the chair, keeping a close eye on the two slices of tightly-drawn curtains, feeling like someone had fastened a rope round my neck from the back, and encircling my neck with his fingers. I couldn’t breathe, my whole body was shaking, though I did not break out into a cold sweat. Not even a single drop of perspiration was to be found on me, my skin as dry and calm as my wakeful consciousness, which, unbeknownst to me, had in fact been long asleep.

I have never made an irrevocable break with my basic ability to reason. But as I stood up, drew the curtains apart and climbed onto the windowsill, absolutely prepared to jump at any given moment, that was the closest to death and the furthest from everything else I had ever been. Thought was impossible, the only thing within reach, at hand, was death, and dying was the sole means of diversifying life: I did not want all my eggs to be in one basket. How secure and concrete my logic felt. I dreaded nothing. When all the street lamps are so brightly lit, and you can see the end points of all the roads, there’s nothing left to dread, there’s only the impulse to walk right up to them with no hesitation.

My friend pushed open the door to the room to see half of my body hanging out the window. She went directly down on her knees at the door, half-crying, half-begging me to get back down, and I started to cry along with her. As always, once I start crying, I can’t stop. Half-crying, half-talking to myself, I gave myself an energetic little pep talk; trying to see myself the way an outsider would, how normal I could seem; telling myself to stop envisioning my body as a weapon, that the real risk to take with life’s adventures is not that of running amok like a headless chicken.

After the incident passed, when I brought it up to my friend, she said that she had slept through that night without waking. She had most certainly not witnessed me in the midst of a suicide attempt; it must all be a hallucination on my part. She repeated umpteen times: “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

For a long time after that, I tried to copy—in solitude, in silence, in secret—the way other people led their lives. That’s also when I started taking medication. I told the doctor that sometimes it feels like I am rising, flying, and other times it feels like I am sinking, descending. Sometimes I land on the top, other times I land at the bottom, though neither state can last for too long. He prescribed me two types of medicine. One was a red capsule, the other a white pill. When you’re on the top, he said, take the red capsule, and when you’re at the bottom, take the white pill.

To be honest I don’t see how the medication has truly changed me for the better, though it has brought the occasional balance. But there are also the times when I take the wrong medicine. Once, I mistakenly identified myself as being at the bottom, when in fact I was on top. Having eaten the red capsule, all night I felt like I was lying on a flying bed watching a soccer match, what’s more, I was busy spitting my saliva onto the faces of the opposing team’s fans, and using my lighter to burn the jerseys of the opposing team’s players, all this despite the fact that I don’t ever watch any form of competitive sport.

It was piercingly bright when the lights were on, but it was too dark with the lights turned off, it was too warm and dry with the heater on, but too cold without it. I wanted to go for a walk downstairs, but I was fearful of waiting for the elevator. Even if I didn’t have to wait for the elevator, I was fearful of the elevator being full of people when its doors opened. I was afraid that these people would see me, and I was even more afraid that I would see them. Any number of hours passed during which I had no clue what I was doing. I did nothing, yet I was fearful of everything.

Half a month after the stayover, the first thing I did upon waking up every afternoon would be to look for my medicine, although this routine made me more panicky than ever before. If I didn’t take my medicine, or if I couldn’t be sure that I had my medicine on my person wherever I went at all times, I would feel completely incapacitated, and ready to implode at any second. Furthermore, the drugs seem to heighten one’s sensitivity to internal perception and expand one’s porousness to absorbing external stimuli. In reality I want so badly to return to reality, but reality is incomparably absurd. The moment I realized I was developing such a reliance on the meds, I stopped taking them at once, so when you brag to me about the absurdity of the world, I’m no longer jealous, not even one bit. I choose to go on believing and remaining in my breakdown, yesterday I was breaking down, but this is still my most proficient and practiced means of survival.

2015.08.06

I raise my head

And lower it

The sun at times

Hardly seems like the sun

But still it insists on shining on me

The road at times

Hardly seems like a road either

Still it tries to dissuade me

2015.08.17

Waiting for the subway each time accompanied by an impulse to jump onto the tracks.

2015.09.24

One night I got home, lay in bed, and the whole room became a prison cell. Moonlight shot through the metal-grilled windows to cast tracks of gridded shadows on the walls. I simply could not understand—how had I shut myself into a prison cell? Suddenly I felt that every time I left the house it was a burst of R and R. I am constantly afraid to head out, but once I’ve decided to do so, I make it a point to wind my spring up well. I don’t ever show my illness in front of my friends; even if those ludicrous nerves, anxieties, panics or exhaustions unexpectedly try to push themselves to the surface—I’ve prepared various protocols in my head to deal with them.

But no matter how careful and vigilant I am, there are still times when the spring unlooses itself with no warning. Watching my friends burning up the dance floor all of a sudden I’m afraid I can’t go on anymore. I am always the wet blanket, afraid for my friends to see me like this—my narcissism—how I wish I were able to behave like I was more into whatever is going on around me, but in those moments, the more convivial the atmosphere, the more distant I grow inside, like all the lights can’t reach me, can’t shine on me. I’m standing alone in an upright coffin. The music they hear doesn’t even seem to be the same as the music I’m hearing, why is the music I hear so sad? Every song sounds like a dirge. I tell myself it must be because I’ve had too much to drink, that or I’ve not had enough sleep.

I sneak off to the toilet to cry.

After some time, the people waiting for the toilet start banging on the door from the outside. I shout back without knowing what I am saying. When the banging stops I calm down, slowly. I lower my head to look at the toilet bowl and it feels like I’m sitting on the mouth of a well. Someone at the bottom of the well won’t stop calling my name. At first it’s just one person, but then it builds up into a chorus of many, or it could be an echo effect, and at that moment I want nothing more than to stick my head down there. There are abysses everywhere. Nobody can genuinely embody the pain of another, and so no one is able to provide true comfort.

Every morning I wake up wondering why I am still alive. I carry this question with me as I live on, but not because I expect an answer.

2016.05.04

Once I sit down, I can’t stand up, I sit on the bed, the sofa, the toilet, the stairs, the floor—merely sitting—can’t say if I’m happy—or not—sad—or not—while inside me I am negotiating with myself. The content of the negotiation is concerned, namely, with whether I ought to get up, or lie down.

Most of the time I end up lying down.

Looking in from the outside, the movement must look like I’ve fallen down. In just a second I feel hoary and weak, my face is as flat as the surface of a lake, a breeze blows, the wrinkles spread like ripples over my face. How to make you see just how real this all feels? I can stretch my hand to touch the gully. I can feel the outflow, drop by drop, of water from my body, and even my bones are beginning to soften into a malleable mass. If you saw me, you’d no longer be able to use “a being,” “a person” or “an occupation” as descriptive nouns; you’d only be able to use “a heap”; “a shore”; “a strand.” I’ve become less than nothing, better than nothing.

I dare not tell you how I feel. I fear you’ll take it for a show of hypocrisy, look upon it as a performance I’m staging.

In truth, there are no words precise enough to express any of this, anyway. Actually, I’ve started to invent a new language, but I constantly forget my linguistic inventions, because they do not adhere to any logic whatsoever. Every day I am struggling in the space between forgetting and inventing, oblivion and creation. But struggle requires such strength, and in the end I know I have to give up on struggling, too. I’ve accustomed myself to submitting to fate, just like throwing a die that keeps tossing up the same number. It’s only later that you realize that every face of the dice carries that number.

What’s most familiar to me in this room is the bit of ceiling above my head. It’s my sky, a white sky, a sky that never changes with the weather, be it fair or inclement. I had this illusion once that the neighbors upstairs were gods that lived in the sky. I was amused that even the gods had to set for themselves a morning alarm on their clock. Personally I have no instruments or tools that record time. I merely hurl a stone into the darkness daily, and I’ve yet to receive any resounding echo. When I jump, if life is a bottomless pit, wouldn’t falling through that infinity be a form of flying, too?

2016.07.18

When it’s bad, it feels like someone in the opposite block is following my head around with a telescopic sight. At any time, I might be shot. Everything I look at appears to be a weapon. Outside the window, the leaves on the trees look like razors; on the table, forks look like darts. The bottle of Coke is a hand grenade. I dare not eat, nor drink. I sit on a chair, the chair feels like it is about to fall to pieces, I lie on the sofa, the sofa might cave in at any time. I want to leave, but every flight of stairs is a precipice on a cliff, each step an abyss.

I make it to the street, but all the pedestrians are vases, of all imaginable shapes and sizes. I would like to buy a bouquet of flowers, so I can stick a stalk into each of the open mouths gaping from their heads, though I know this world won’t become any more beautiful as a result of that. I’d be better off with a hammer. Killing someone would be as easy as smashing a vase in. As easy as the way people can be murdered by the mundanity of life itself—at the very least I know it is capable of killing me, rendering me formless.

All over the floor, the shards look like false teeth twinkling crisscross spots of light in the dark. Wave upon wave of nausea rolls inside of me as I hallucinate my rebirth.

It was my constant assumption that everyone has such experiences too.

For example, before I fall asleep, I often feel as if my tongue has been flushed with helium. Slowly it grows light, tender and swollen, the inside of my chest stuffed full of cotton, expanding and infecting every inch of my body till finally all I am is a huge wad of cotton, floating midway in the air. Sometimes the body and the bed float together, sometimes they float apart, other times only the body floats, and if you lower your head, you’d see the neatly-folded bedclothes looking perfectly untouched.

On insomniac nights my whole body is charged with forceful energy. This force controls me, has me do nothing, has me want nothing. One method I have is to place my watch on top of my ear, trying to match, step for step, my heartbeat to the ticking of the second hand. Occasionally this provides a smidge of relief, other times it makes me sigh at our powerlessness in the face of time’s passage.

Sometimes the night is preternaturally silent, sometimes it is clamorously loud, when it is silent you will feel like you are the only person left alive in the world, when it is loud you will feel like you are the only person dead to the world. Wading into the darkness, the lamps around you turn bright, but once you cross into the light, the surrounding sky darkens. How can I not have my suspicions—that this light isn’t a vivid bolt thrown down from the heavens?

In any case: you’ve certainly never believed in fairness. You’d willingly tie weights to every part of your body and jump into a river, a sea. You’ve always felt like you were separated from this world by a layer—sometimes a sheet of fog, sometimes a piece of glass, sometimes a wall, sometimes a mountain, sometimes not just one, but two or even three dimensions. Loneliness looks like the jadeite reflection of the moon in a pond. You go to caress it, but all your fingers can do is tease up a spiral of ripples.

It was only after querying numerous people that I discovered that none of this is familiar to them.

Life is not such, life is such: in short it will never be how you want it to be. Just like when you’re dying for a smoke, but you haven’t got any cigarettes, then you’ve got the cigs, but you don’t have a lighter, then you’ve got a light, but there’s no flame, and when you finally get a flame going, you don’t feel like smoking anymore.

Boredom and pain are regular states of being. Happiness and luck are aberrant states. Mania causes fatigue, comfort leads to dread. Fatalism might be the best and only way to go from here.

2016.07.19

On insomniac nights, once I shut my eyes I see unending visions of me engaging in every possible manner of suicide. Frightened out of bed, I search the house and lock up all the sharp objects I can find into a drawer. There’s a pair of scissors so large it can’t be jammed into the drawer for the life of me. I fling the scissors, along with the key to the drawer, out the window. I lie on the bed perspiring in waves, my body fevered, though I still feel cold. I feel as if I am bleeding, every joint in me tender and pulpy like a freshly-made cut, my whole body a giant wound. I should like to bandage myself up. I should like to eat a pill the size of my bed.

2016.09.17

Of late I’ve found a new means of calming myself down. Tripping and taking a fall can be a counterbalance to depression. Each time I hit the ground, I lie absolutely flat, making it easy for pedestrians and vehicles to step across or roll over my body. In these moments, consciousness and intuition become incomparably clear. Even wisdom and memory seem heightened. All significant events are vivid, to the extent that one is even able to expatiate at length on the words spoken by relevant parties.

The year was 1997, the place was in jail. Bai Baoshan said: When I get out I’m going to kill people. If they sentence me to twenty years, I’ll get out and kill adults. If they sentence me to life imprisonment and I get out early on parole, but I’m too knackered to kill adults, I’ll head for the kindergarten and kill some kids.

I am always hearing gunshots.

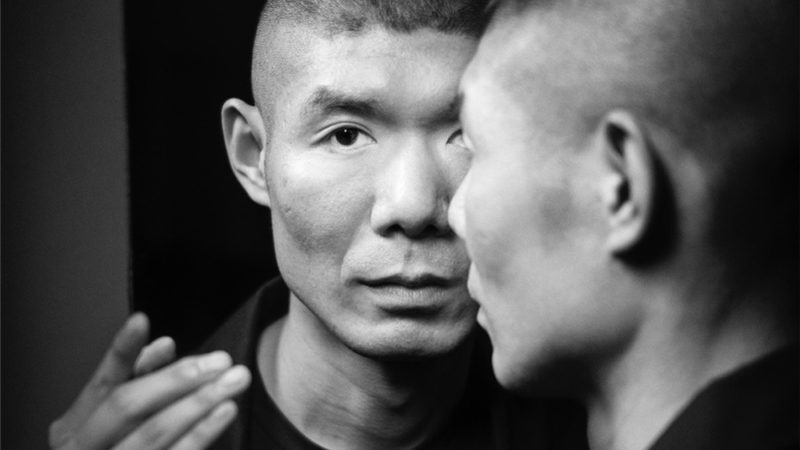

In the beginning it scared me a little, but over time I’ve grown used to it. Someone has taken up a hammer and is knocking nails into my head, it’s a construction site where someone is erecting a monstrous skyscraper, they’ve been building it for doggone years and it still isn’t done yet. The many homeless people in my head are crying and jibing, they won’t let me sleep, won’t let me out the door. Staying home and awake suits me just fine, because every day before heading out, after putting on the clothes I’ve selected so meticulously for myself, and looking into the mirror, it looks to me as if I’ve dressed to attend my own funeral, grandiose and somber. Every destination is a memorial hall I am rushing to to mourn myself.

I am afraid, too, of stepping out and hearing the concerned, the doubtful: “You look so happy, how could you possibly be depressed?” “You’ve no reason to be depressed, I’m the one who’s depressed.” “You’re such a hypocrite.” “There he goes again…” These voices make me more nervous than the ones in my head do. In every social situation involving two or more other persons, I am either talking incessantly, or absolutely silent throughout. All pretense of ease drains me to the bone.

For so many years I have been trying to treat my own illness. One person splitting dual roles of doctor and patient. Sometimes the doctor sees the patient, other times the patient sees the doctor, too. I have thoroughly remade my life into a hospital, hanging around the many different wards each day. The people on the outside cannot enter, but I can’t walk out, either.