In his latest book, Mamdani attacks the Save Darfur Coalition as ahistorical and dishonest, and argues that the conflict in Darfur is more about land, power, and the environment than it is directly about race.

“The Save Darfur movement claims to have learned from Rwanda,” writes Mahmood Mamdani in his new book, Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror

“The Save Darfur movement claims to have learned from Rwanda,” writes Mahmood Mamdani in his new book, Saviors and Survivors: Darfur, Politics, and the War on Terror. “But what is the lesson of Rwanda? For many of those mobilized to save Darfur, the lesson is to rescue before it is too late, to act before seeking to understand.” His book is an argument “against those who substitute moral certainty for knowledge, and who feel virtuous even when acting on the basis of total ignorance.” Americans think Darfur is a tragic genocide. Mamdani thinks the reality is more complex. His ideas should be taken seriously for a number of reasons, especially because he provides a road map to a workable peace settlement.

Mamdani rewrites the crisis by putting it in context. He notes that violent deaths in Iraq during the U.S. invasion and occupation far surpass death rates in Darfur. If death rates are higher, why all the attention on Darfur, rather than Iraq? he wondered. Is the killing racially motivated? To answer that, he examines the history of Sudan.

The people of Darfur have long treated “racial” identities as fairly fluid, he writes, welcoming intermarriage as a means of transferring between groups. Why does this matter? The designation of “Arab” versus “African” upon which the genocide claim is based was given a particularly virulent, and unprecedented, authority under a land system set up by the colonial British—but never before that. After the British, land previously shared was now assigned a more rigid “native” group who oversaw its use, and non-native groups who had to pay tribute. This was one potential source of conflict; it will have to be dealt with to forge a lasting peace in Darfur, Mamdani insists.

Then a decades-long drought turned fertile lands in the north of Darfur into desert (in a process known as desertification). This made land use and land rights much more contentious. In his attempt to “contain” Libya during the Cold War, U.S. President Ronald Reagan armed rebel groups from Chad. This meant that, along with the Soviets and Libya on one side, and Israel and France on the other, Reagan helped arm a region already on the verge of erupting.

What resulted was a civil war; the first phase, in the late nineteen eighties, began with savvy opponents who accused each other of atrocities in a somewhat sophisticated PR war. Phase two began with a 2003 insurgency that met with a fierce response from the government. An ongoing massacre? Massacres occurred early in the conflict, admits Mamdani. But starting in 2005, death rates dropped drastically. Save Darfur had no interest in this decline in direct killings, having staked their campaign on the story of ongoing genocide. Arabs hoping to wipe out Africans? Not really. Rather, a land war amidst the throes of desertification. According to Mamdani, this is an ecological disaster amidst a land divided on paper by colonial rulers, and militarized by the Cold War, not a crisis directly about race. In fact, Mamdani argues, the language of genocide further exacerbates the conflict. It keeps key groups out of peace talks by demonizing them. This is exactly what happened during peace talks in Abuja in 2005, he says.

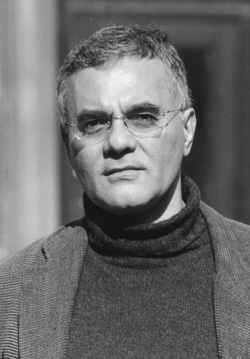

I spoke with Professor Mamdani in his office at Columbia University in New York City. Named by Foreign Policy magazine as one of the top one hundred public intellectuals, he wore a blazer, a bright red polo shirt with a Nehru collar, round-rimmed glasses, and a five-o’clock shadow; his eyes showed a tired face—from the end of a semester and the middle of a book tour. A handsome man born in Uganda to parents with roots in India, he spoke quietly, breaking his sentences with long pauses. Sitting atop his coffee table, incidentally, amidst a slew of other books and journals was The Crisis of Islamic Civilization by Ali Allawi (who made a similar charge against the U.S. acting before understanding, in The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace

). In addition to teaching in the anthropology department at Columbia, Mamdani served for a year as consultant for the Darfur-Darfur Dialogue and Consultation (DDDC) of the African Union. He is married to the filmmaker Mira Nair; they live in New York and Uganda and have a son, Zohran.

—Joel Whitney for Guernica

Guernica: Here in the United States, what is the story that has come down to the public about Darfur?

Mahmood Mamdani: I think the core of the argument is very ahistorical. It’s about Darfur as a site of evil; the narrative is structured around a documentation of atrocities, around a graphic description of atrocities, which you can see on the Save Darfur website—killings, rape, burnings of villages. I think the striking thing about the narrative is there is no attempt to explain what leads to these atrocities.

Guernica: You write how one problem is the word “genocide.” Of course, policy people know that the word genocide has legal ramifications. But you say it’s not a genocide in Darfur at all.

I mean you have an insurgency and a counter-insurgency. The assumption is that all those were killed by one side.

Mahmood Mamdani: I’m saying two things, that there’s no attempt to eliminate a people here. This has been a conflict over land. In the way it originated and the way it developed in its latest phase, in 2003, it has been a conflict over power. These have been the two dimensions of the conflict. The second thing I would say is that in a very early phase of the conflict, in 1987-1989, which was that of a civil war, one side of the civil war was already using the language of genocide; the word used was “holocaust.” And the other side was talking of being at the receiving end of ethnic cleansing. The genocide narrative is simply repeating one version of events.

Guernica: In your book, you seriously challenge the numbers of dead cited widely by the media. I think there’s a pretty widely held consensus that in 2003-2004 there are, let’s say, emergency numbers of dead. But what about the beginning of 2005?

Mahmood Mamdani: Well, 2003-2004, there’s a mass slaughter.

Guernica: By?

Mahmood Mamdani: Well, good question. Let’s first begin with the easier question, numbers. Because there we have some hard figures, and a debate on it, and sort of an experts’ report from the Government Accountability Office, and a pinpointing of which are the most reliable figures by WHO/Europe CRED (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters), which says that something like one hundred and twelve thousand people died excess deaths in this period. And it says there are multiple causes; there’s violence, there’s disease, there’s starvation, desertification; it says thirty-five thousand roughly are the product of direct violence. The debate is over the rest. How much of it is violence-related? Babies [who] died of dysentery or diarrhea? If there had been no conflict, [would] help have arrived in time? That’s the debate. But keep in mind that the desertification preceded the violence. So it has to be treated as a separate cause—related but separate. So of those who died by conflict-related causes, who were they killed by? The participants in the conflict? I mean you have an insurgency and a counter-insurgency. The assumption is that all those were killed by one side.

Guernica: But you write that the killing slowed starting in 2005.

Mahmood Mamdani: In September 2004, the rates start coming down dramatically.

Guernica: I’ve even heard you credit Save Darfur for drawing some attention to the killing and getting Sudanese President al-Bashir to pull back. So that’s remarkable. Your book’s being seen as an attack on Save Darfur…

So there was a dramatic decline in killings. But these guys [in Save Darfur] kept on telling us that mortality was increasing, a continuing genocide. They were unwilling to let go of this genocide narrative and were unwilling to let go of their solution, an external intervention.

Mahmood Mamdani: It is an attack. I have very serious criticisms of Save Darfur.

Guernica: But you do credit them with that first decline in killing.

Mahmood Mamdani: I credit them not with the decline; I credit them with the publicity.

Guernica: …that helped lead to the decline?

Mahmood Mamdani: Yes. That’s what I mean. Having achieved that, ironically, they seem to have no interest in the decline. None whatsoever. So they’ve never acknowledged the decline in public. They never saw the decline as an opportunity for a political settlement.

Guernica: And death rates coming how low?

Mahmood Mamdani: Below two hundred a month since January 2005. And the sources are UN figures gathered by Julie Flint in The Independent. Then below one hundred and fifty a month from January 2008. That source is the commander of the UNAMID forces, and [a report] the Security Council’s envoy just gave to the Security Council last week. So there was a dramatic decline. But these guys [in Save Darfur] kept on telling us that the mortality was increasing, a continuing genocide. They somehow were unwilling to let go of this genocide narrative and they were unwilling to let go of their solution, which was an external intervention. Basically, my point is that there was an opportunity for an internal solution. The external influences should have brought to bear their influence on this internal solution instead.

Guernica: You have written that the racial component, of Arabs trying to eliminate Africans in Darfur, is false.

Mahmood Mamdani: [When I looked into this] I began to run into micro-histories, and into folklore and into anthropological studies which clearly showed that there wasn’t a single history of Arabs. That actually there were many histories of many groups becoming Arabs at different times, for different reasons. Kings claimed to be Arab because they claimed a connection with the Holy Land. Merchants became Arabs hundreds of years later with the explosion of a mercantile civilization in central, northern Sudan, around the Nile, eighteenth century. Former slaves became Arab. They took on the identity of their slave masters. So this Arab/settler business made no sense, and this business of a single Arab history made no sense. But the business that the riverine Arabs (around the Nile region of Sudan) were the same as the Darfuri Arabs made no sense, because riverine Arabs are identified with privilege and power, and the Darfuri Arabs are identified with the absence of privilege. What I realized is that these are African Arabs. These are not Arabs who came from anywhere else. But the media were raising this narrative of Africans and Arabs, linked with slavery, and I just thought I had to write about this.

Guernica: What needs to be better understood about the Janjaweed?

Mahmood Mamdani: These fellows were there from the mid-nineteen eighties onward, when the crisis of desertification hit its high point. Janjaweed referred to bands of youth, not centralized in their control of the organization, [who were] initially the product of an acute crisis of marginal peripheral lands in the throes of desertification. [It was] a crisis of youth, which was much broader than simply Darfur or even Chad. You can even find it in Congo or different places. The interesting work that the narrative on Janjaweed has [done has been to] justify the exclusion of the Arab tribes from the Abuja peace talks. The Abuja peace talks were between rebels and the government. And rebels were one side of the civil war who had grown from being tribal militia into rebel movements. And the other side of the civil war, which had remained tribal militias—and some of whom had joined the government, and were the Janjaweed that you’re talking about—got left out. You can find another example of it in the war on terror language, whether Hamas should be included in talks or should not be included.

Guernica: So the story of the Janjaweed as hired mercenaries paid in loot at the behest of the government to ransack villages of innocent people, sometimes following air raids with government planes—that story is not accurate?

Mahmood Mamdani: Part of it is accurate, but part of it is not. If you understand them as just mercenaries for an end determined by the government, that’s the part that is not quite right. Because if that were true, then the government would have had no problems with them. The problem that developed between these nomadic militias and the government was that these militias had their own objectives. And these objectives in fact preceded the beginning of the insurgency beginning in 2003, and they included land. So no matter what the political consequences for the government, that’s the objective which drove them, and the government realized it didn’t really have control over them. And the [nomadic militias] realize that the government would have no trouble dropping them if it served the government’s interests, and [some of them] try to turn into rebel groups, and so out of these you get so-called Arab rebel groups.

Guernica: And what role did the colonial British play?

Mahmood Mamdani: The British engineered the grand narrative. The British inscribed it in the census. The census had three categories: tribe, groups of tribes, and race. The groups of tribes are basically what the anthropologists understand as ethnicity, which is a language group—tribes that speak the same language. Then there was this thing called race. And they had five races there: Hamites, Nilotics, Arabs, Negroes, and then Negroid Westerners. Negroid Westerners were Negroes in Darfur and Kordofan. So the Arabs were classed as a single group whether they came from Darfur, Kordofan, or anywhere in Sudan. To what extent did the categories in the census translate into public policy? Here it is the category of tribe which was the fulcrum of public policy. So Darfur was divided into tribal homelands. The tribe that was considered the “native” tribe had customary rights to the land. And anyone considered to be an outsider would have to pay tribute. Tribe became the basis of systematic discrimination. So you got settler and native as a tribal distinction. When does this become a racial distinction between Arab and African? I think it becomes that with the civil war in the mid-nineteen eighties and it grows.

Guernica: And what role do Ronald Reagan and the Cold War play here?

Mahmood Mamdani: There are three causes of the civil war, what I just described about customary land rights for native tribes. Overlaid on this comes the climate change, the Sahara advancing one hundred kilometers over four decades. By the mid-nineteen eighties, you have no water, and the place is awash with guns and those guns are an effect of the Cold War. When Reagan comes into power, the U.S. one day declares Libya to be a terrorist state. From there, Chad, Darfur’s neighbor, becomes part of the Cold War. On one side, you have the alliance of Reaganite America, France, and Israel, and on the other, Libya and the Soviet Union. They arm different sides in the Chadian civil war. One group is in power in N’Djamena and the other group crosses the border into Darfur. Darfur becomes militarized. And the present government in Sudan was not even in power at that time. The big powers get involved way before the government of Sudan gets involved.

If Iraq was seen through a political lens, Darfur was seen through a moral lens. The language of genocide did that work very effectively.

Guernica: With their Reagan-Republican/Cold War beginnings, maybe that now brings us back to how Iraq parallels Darfur. In the London Review of Books, you write, “The similarities between Iraq and Darfur are remarkable. The estimate of the number of civilians killed over the past three years is roughly similar. The killers are mostly paramilitaries, closely linked to the official military, which is said to be their main source of arms. The victims too are by and large identified as members of groups, rather than targeted as individuals. But the violence in the two places is named differently. In Iraq, it is said to be a cycle of insurgency and counter-insurgency; in Darfur, it is called genocide. Why the difference? Who does the naming?” What’s the link between Iraq and Darfur?

Mahmood Mamdani: Well, I was actually wrong on those numbers. The numbers in Iraq are much higher, if you go by any estimate.

Guernica: The rate of violent deaths in Iraq from the American invasion and occupation is higher than in Darfur?

Mahmood Mamdani: Much, much higher.

Guernica: What do you draw from that?

Mahmood Mamdani: If you look at the course that Iraq took, it’s very different from the course that Darfur took. The violence in Darfur reached those high levels precisely when the government looked for a proxy through which to confront the rebel movements, and hit on the nomadic militias as the proxy. Iraq didn’t begin as an insurgency; it began as an invasion from the outside, and [then came] the resistance. And the solution to the resistance was supposed to be—El Salvador-style—a civil war. And the civil war did undercut the resistance but at a huge cost. Numbers of the dead multiplied. Whereas the understanding of Iraq was much more political, Darfur was different. If Iraq was seen through a political lens, Darfur was seen through a moral lens. The language of genocide did that work very effectively.

Guernica: You start your book by remarking how odd it was that there was no mass mobilization to stop the war in Iraq. And we could debate whether that’s true or not, whether it turned rather into a political movement to defeat Bush instead. There clearly was a huge movement in February 2003. Millions around the world—in unprecedented numbers—marched to stop the Iraq war. Is it your contention that that energy became the Save Darfur movement?

Here the world was not a classroom, it was an advertising campaign.

Mahmood Mamdani: The links are complicated. The media of course was wholly sympathetic to the Save Darfur Coalition, not particularly sympathetic to the mobilization around Iraq. Here on the West side (of Manhattan) in local Jewish communities, resolutions were passed on the Iraq war, which required the leadership to communicate them to the White House, but which were never communicated. In fact, all the energies being invested in mobilization around Darfur—of course what really struck me was that the Darfur mobilization…

Guernica: Are you saying that the Darfur mobilization stole the thunder, stole the energy of the Iraq anti-war mobilization?

Mahmood Mamdani: It became like a shelter. And the constituency began to change. These people reached even lower than the universities, down to high school students. The antiwar movement against the Vietnam war, of which I was a part in the sixties, saw the world as a classroom. Its signature activity was the teach-in, putting students face to face with scholars, to learn about the place, learn about history, learn about politics. There was something called colonialism, anti-colonialism, the ways in which the struggle in Vietnam is linked to this. These were the issues, big issues of the day.

Guernica: And you’re not seeing that…

Mahmood Mamdani: Here the world was not a classroom, it was an advertising campaign.

Guernica: A web page.

Mahmood Mamdani: A web page [with] an advertising campaign. There was no attempt to mobilize scholars, but instead media personalities, show biz personalities, name recognition; no interest in teaching anybody anything, but almost like the Pied Piper and the train of high school children who were supposed to follow.

Guernica: And Samantha Power’s A Problem from Hell reminded us that we Americans were forty years late signing the Genocide Convention and that no president used the word “genocide” while in office. The notable thing about the Bush administration was that he did use “genocide,” but then did nothing. You add a twist when you say it was rather a civil war, or counter-insurgency, that he was calling a genocide.

Mahmood Mamdani: There are two problems with that book. One was the assumption that America would go around the world and carry out a series of humanitarian military interventions, this assumption that the problems of the world are internal and the solutions are external. And the second problem is the assumption that the world is a simple place—you don’t have to think of what causes these problems. Leaving politics aside when it’s genocide [is problematic]. So everything is about this word “genocide.” The word is politicized, instrumentalized.

Guernica: Well, it’s a law. And she’s saying that the law has not been enforced. Isn’t that a valid thing to point out?

Does Moreno Ocampo think that the ICC has a special mandate for protecting “African victims of African crimes” but not Iraqi or Afghani victims of American crimes or for that matter only some African victims of some African crimes?

Mahmood Mamdani: It is a valid thing to point out. But if you asked yourself why… The most likely candidate for having carried out large-scale killings which may be characterized as genocide would have been the U.S. In the Vietnam period, how come no American president talked of genocide? Well, how can you expect an American president to talk of genocide when there’s a whole politics around genocide—which is absent from the book?

Guernica: Okay, earlier you spoke of mass killings in Darfur in 2003 and 2004. From what I’ve read and what you write in your last chapter, it sounds like you oppose the ICC investigating them. Does this mean that the rapes, the mass atrocities which have so clearly been committed, and which have continued in the refugee camps, and which you’ve acknowledged, should go totally uninvestigated and unpunished?

Mahmood Mamdani: I argue that faced with ongoing conflicts mainly fueled by demands for political justice, political reforms should take priority over criminal trials of individual leaders. The precedent has already been set in the post-apartheid transition in South Africa, the end of the civil war in Mozambique, and then in South Sudan. Why not Darfur? For rule of law to take hold, we need both to hold accountable not only perpetrators but also enforcers of law. If there is not an adequate political arrangement to hold enforcers of law accountable, law will turn into a private affair. This was the essence of the Indian government’s reason for refusing to sign the Rome Statute that set up the ICC: since the ICC’s formal accountability was only to the Security Council, the Indian government contended, the ICC would never bring any permanent member of the Security Council to justice. The experience of special prosecutors in the U.S. also shows that when there is inadequate political accountability such persons can turn into rogue prosecutors pursuing a private agenda.

Guernica: On what basis do you see the court as a western court, as you wrote in The Nation?

Mahmood Mamdani: The fact that the court is answerable to the Security Council means that it will create a regime of impunity for its permanent members and their close allies or clients. Anyone following the practice of the court since its creation will find these fears warranted. At the same time, the attempt to turn justice into a turnkey import from the outside cannot possibly enhance the rule of law inside Sudan. As I wrote in The Nation, when Africans realize that the four arrest warrants the prosecutor has applied for are all of African leaders without strong patrons in the West, it confirms their fears that this is a Western court created to hold accountable those African leaders branded as heading “rogue states.”

Guernica: When I cited your charge to him, ICC lead Prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo bristled at the idea, insisting first, by the way, that he himself is not “Western;” as an Argentine, he sees himself as Southern. He also pointed out that in the three African cases he is working on apart from Sudan/Darfur, the African leaders of those countries themselves invited him. While the Sudan case was referred by the Security Council, the pre-trial judges that awarded him his warrant were Akua Kuenyehia from Ghana, Sylvia Steiner from Brazil and Anita Usacka from Latvia. Hardly a Western Court. Not to mention that he was looking into initial investigations in places like Israel/Gaza too, at the time we spoke. But within Africa he insists he is protecting African victims of African crimes. Do disputes over Vietnam-era colonialism negate the need to protect African victims today?

Mahmood Mamdani: Does Moreno Ocampo think that the ICC has a special mandate for protecting “African victims of African crimes” but not Iraqi or Afghani victims of American crimes or for that matter only some African victims of some African crimes? We have been through an era known as “the war on terror,” where a global war set an example for so many little wars on terror regionally. In all instances, state terror was unleashed on civilians with impunity. How shall we look at a court claiming to be an International Court of Justice—with its personnel as internationally recruited as that of any World Bank or IMF team, or any Wall Street bank for that matter—but steadfastly refusing to bring to justice the perpetrators of the larger war on terror and several regional ones in its tow, instead focusing only on state terror unleashed by those without American protection? Does it not begin to look more like street protection guaranteed by street gangs or war lords than a rule of law? I suggest you take your clues from the actual performance of the ICC rather than the stated intentions of its prosecutor.

Guernica: Howard French wrote of your book, in an otherwise very positive review in the New York Times, “This important book reveals much on all of these themes, yet still may be judged by some as not saying enough about recent violence in Darfur.” Given how active some of the Save Darfur Coalition has been in visiting the internally displaced people (IDP) and refugee camps, I wonder, how many survivors of attacks did you interview for your book? How many of the refugee and IDP camps have you visited?

Mahmood Mamdani: I was a consultant for the Darfur-Darfur Dialogue and Consultation (DDDC) of the African Union for a year. The DDDC held consultations with different sections of Darfuri society in the three states of Darfur. Typically, day one would be a meeting with traditional leaders (chiefs, etc.); day two with representatives of political parties, government and opposition; day three with community-based organizations; day four with representatives of women’s groups and intellectuals based in each of three universities in the three states of Darfur; and day five with representatives of IDPs in the camps. My job was to read the submissions of different groups, to listen to the discussions in each consultation, and to point out which issue needed more attention and which point of view was left out of the discussion. It was an ideal job for a researcher.

Guernica: But it’s still not clear: how many refugee and IDP camps did you visit directly?

Mahmood Mamdani: I have not been to an IDP camp in Darfur but I have had intensive discussions with IDPs in Darfur. I am also no stranger to refugee/IDP camps, having lived as a refugee in one for months following Idi Amin’s expulsion of (Asians from Uganda in) 1972 and having done numerous interviews in IDP camps in northern Uganda.

Guernica: You mentioned that you wanted to start a debate with the Save Darfur Coalition. Have they engaged you at all?

Mahmood Mamdani: The only contact since the publication of the book has been the debate with John Prendergast at Columbia.

Guernica: What’s next for you? I understand you’re back on book tour soon. And do you plan on doing more debates with anyone from the Save Darfur Coalition?

Mahmood Mamdani: [I next go to] Toronto and Chicago talking about the book. I have a week-long commitment in early June in the UK starting with the Guardian Hay Festival and then 10 days in South Africa starting with the Cape Town Book Festival. I have no idea as to whether there will be future encounters with Save Darfur.

To read Luis Moreno Ocampo’s views to the contrary, go here.

To contact Guernica or Mahmood Mamdani, please write here.