There were two of them, pssting at me from the murk beneath a palm tree, along the jungly trail that twisted off to the shantytown. In grubby board shorts, shirtless, the slim one sat with a towel around his shoulders. The burly one stood behind, brandishing cordless clippers, and buzzed his friend’s blackish hair with tender brutality. Even from thirty feet away, out on the white-sand lane, I could sense the fresh crew cut’s effect: his head looked newborn, true. A blank slate.

“Oi,” he beckoned. “Oi, brother!” He used the English word but Brazilianified: broa-der.

I glimpsed his waving arm, its skinny animation, but not his face, not in any detail. The sky was starting to blur with dusk, and of the scarce streetlamps along this shortcut between the kombi stop and our surfside guesthouse, only one gave out any light. I’d watched boys all over the island using such lamps as targets, pelting them with beer bottles and rotting coconuts; when the bulbs burst, the hooligans cheered “Gol!” But this kid and his roughneck pal were older—eighteen? Nineteen?

“Brother,” the slim one called again, his voice sharp with nerve. Then he added, in Portuguese: “Please? We just want to use your cell phone.”

This was my third trip to Bahia, after projects in São Tome and Mozambique, and I could handle basic conversations in the language. “Sorry,” I said. “Don’t have one.” I didn’t break my stride.

“Liar!” yelled the tough with the clippers, squaring his brawny shoulders. “How stupid do you think we are? Liar!”

A stunted mutt, scared by the shout, bolted from the bushes, but just as soon forgot its fear and fervently stole some fish bones from an overflowing wire cage of trash.

“Sure, I have a phone,” I said. “Not with me.”

“Seriously?” said the lean kid, goadingly rubbing his crew cut. “I thought a gringo always has his smartphone.”

Another two hundred yards and I’d be safe at the folksy guesthouse, with its hammock, its icy caipirinhas. I’d suffered a sticky, mosquito-addled day in a boondocks village, dickering with farmers about a loan for their heart-of-palm plantation. No matter that the interest rate was already close to nil, and that my services and the environmental adviser’s were pro bono, the farmers wouldn’t let up on their haggling. Forget it, then, I wanted to say. Stick with your current pittance. Instead, I grinned my do-gooder grin and told them yes, I understood. Yes, of course, I’d see what I could do.

But now this cheeky, crew-cut punk, his brazen heckle (gringo!), had severed the last thread of my politeness. “Carry my phone here?” I said. “Where I might meet a thief?” Thief was one of the first words my Portuguese coach had taught me, a satisfying nasal sneer: ladrão.

He stood up slowly, smiling, shaking out his towel. Theatrically he snapped it, and the world at once was weaponized: towel, clippers, fists. (Vagner, the guesthouse owner, had warned me about the shantytown; “crack” was all he’d said, all he’d had to.)

“Why are you alone?” said the kid, sauntering halfway toward me. He swept clipped hairs from the hollow of his scrawny, meatless chest. Just this easily, he seemed to say, I could dispense with you.

I looked ahead, behind: no one on the lane. The only building, a shuttered vacation home from the island’s boom days, sat dark behind its wall of concrete studded with jagged glass.

“Why?” he repeated. “Where is your sexy wife?”

“You don’t know me,” I said, ready to sprint. “Leave me alone.”

“No, no, your wife,” he said, and staged a vulgar pantomime, swinging his hips, hefting imagined tits. “Where is she today? Where is Marisa?”

I stopped short. Were they stalking her? “How do you know her name?” I said. I took a hard step closer. “Tell me. How?”

He didn’t flinch; he laughed. “Now you defend her? Good!” he said. “Not like yesterday: ‘Stop, Marisa. Marisa, stop, please.’” He sang the words in lilting, malformed English.

The gossipy little tune sapped some of his menace. What had Marisa and I been sparring about, the day before? She’d been overpraising my tact with the local land agent, and I’d been trying to tamp down her sweet-talk.

“She’s not my wife,” I said, guessing he meant no harm. “Just my”—what was the word for co-worker? Come on, what was it?—“my friend.”

“Oh, a ‘friend.’ Nice,” he said. “Friends can be more…fun.” He grabbed his crotch and, giving a low grunt, stirred it.

Now I was laughing: at the pureness of his swagger, and at his conviction that I, at thirty-eight, balding, plain-faced, was sleeping with a looker like Marisa. Or with any woman, for that matter. I found it—found his cocksure act—impairingly seductive.

“Today she didn’t come,” I offered. “Sick, you know? Her stomach?”

“Ai, the gringos. Always sick! They want so much to taste our island life, but the gut says no. And you?” he said. “Your stomach is hard and strong?”

“Me? Oh, yes.” I patted my paunch. “The stomach of a baiano.”

He nodded warmly, clearly amused I’d called myself a local. He didn’t need to know about the prophylactic Cipro I’d been taking twice a day since I arrived (the script written by Craig, my internist husband).

The burly kid approached now, too, revealing his darker face, his broody brow. He paused to squint judgmentally (would he call me a liar again?), then sprang forward, bellowing something. I stiffened, stumbled back. On he barreled with bullish, galumphing charm, his cheeks dimpling. “Come!” he was saying. “Forget the cell phone. Have some coconut. The water is good for you—makes you healthy.”

Even now that I got his words, I felt a little shaky. No, I told him, I had to go, they’d miss me at the guesthouse. I should see if Marisa had improved.

“Later,” he said dismissively. “Now you’re here, with us. You must live!” He opened his arms invitingly, like someone in a travel ad.

The lane was still deserted. Even the dog had fled. My sped-up breaths infused me with a tingle of remoteness. I stood there in the dimming light, letting the island’s evening soundtrack throb against my skin: hymning frogs; the sly swish of monkeys in the mango trees; from down the lane, the sea’s endless applause.

“Maybe the gringo is just too [something],” the kid with the crew cut said, using a word I didn’t recognize.

“Yes, I think,” said the bigger one. “Too [something] to be with boys from the street, like us.”

“No,” I said. “Come on. How can you say that?”

“Well,” he said. “Then so?”

The day’s heat had dissolved into a briny, pricking breeze. The air itself seemed to egg me on. “I guess…,” I said, “I guess, okay,” and started down the path.

He punched his muscled arm in the air, huffing a note of triumph. “Jonas,” he said, and thumped his chest, by way of introduction.

“Carl,” I said, close enough now to shake his rocky hand, and to see the scar, in the shape of a sickle blade, below his ear.

The lean kid gave me a fist bump and a giggly, bright “Beleza!”

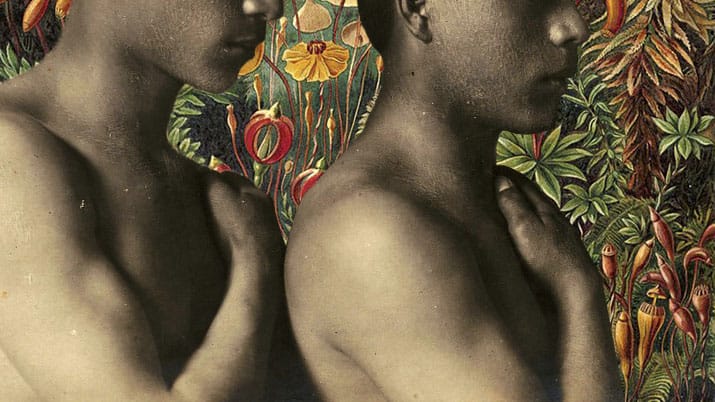

Beleza was right: the guy was beautiful. Something about him reminded me of the stray who’d nabbed the fish bones. His ribby chest, but more—his slinky, antic zeal. Craig, who was black, had schooled me not to liken a person of color’s skin to spice, and so I tried not to think of cinnamon or nutmeg. But this kid’s shade was less a color, anyway, than a mood, like one of those impressionistic names they give to paint: Tornado, or On the Brink, or Zoom.

“Wellington,” he said proudly. “My name.”

“Wellington? Like the boots?” I said.

He gave me a muddled look, poking his tongue at the hole left by a missing upper tooth.

“The British ones,” I added. “The ones—”

“Just call me Well,” he said. “Exactly like the word in your language, no?”

He and Jonas exchanged some talk I couldn’t understand, a whispered rush of which I only caught “could be” and “later.” Then Jonas scampered off to procure a coconut, while Wellington grandly insisted I take his seat, one of the flimsy plastic chairs ubiquitous in the bars here, this one yellow, marked with the Skol beer logo. He’d be happy, he indicated, to squat on the sandy ground.

When I sat, the chair buckled. I gasped, flailed for balance.

“Maybe no coconut for you,” he said good-naturedly. “Too fat!”

At home, I was a touch plump, but here I felt gargantuan, enthroned above this hunkering origami crane of a kid. “Sorry about the phone,” I said. “I really don’t have mine on me. If I did, I’d let you make a call.”

“No, a phone call? No,” he said. “I wanted to use its light.”

“Its light?”

Yes, he explained: to view the haircut better. “We have a mirror, see?” he said, pulling one from the sand: an icicle-like shard of silvered glass. “Jonas says the cut looks good,” he added, “but I never trust him.”

As luck would have it, I carried a penlight: along with antibiotics, part of my standard travel kit. “Voilà,” I said, unveiling it from my pocket.

“I knew you would help,” said Wellington. “I knew. I said to Jonas.” Directing my aim of the penlight, he held the broken mirror. “And?” he said. “What do you think? Handsome?” He bent his head, rubbing his thumbs along the new-mown hairline, as if testing a whetted blade’s bite.

Something else Craig would say to white folks (excepting me): Keep your snoopy fingers to yourself. Don’t touch the hair! But should I, here, with no one watching? Was that what Wellington wanted? Our gazes met. The penlight made his vital green eyes glow.

Here came Jonas, bounding back, a coconut like a loaded bomb aloft in one raised palm. I turned away from Wellington, but caught a final, mirrored glimpse: his tongue’s wet tip pulsing where his tooth should have been.

In Jonas’s other hand, he flaunted a machete. He sliced the air, gleefully screeching stylized kung-fu shrieks, then dropped to his knees next to me, all smiles. He flourished the coconut, this way and that, like a sommelier with a bottle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape.

“Nice and cold?” asked Wellington. “A good one for our guest?”

“Absolutamente! The coldest one,” said Jonas.

With four chops to the husk, he bared the nut’s white tip, then lopped it off and, finessing the machete like an egg spoon, scooped a sipping hole. He granted me the honor of drinking first.

I downed a gulp, cool and sweet and not unpleasantly grassy, then gave the nut back to Jonas.

With boyish solicitude, he asked, “You like?”

I told him it was perfect, the best I’d ever had—and maybe it was, because of where and how I’d come to share it.

“Great!” said Jonas. “You want some more?”

“Please.” I held my hand out.

“Okay, then. That will be ten reais.”

“What?” I said. “You’re serious?”

His eyes went grave. “They cost money. You think you can just take?”

Coconuts at the beach went for two or three reais.

My lungs felt lanced, useless. Was Wellington in on this, too?

“Porra!” he cursed at his pal. “Jonas, are you an idiot? Carl is our brother. For him, this should not cost ten reais.” He flashed his grin. “No, for Carl? Twenty.”

Wellington, too! A bitter shame came foaming up my throat.

I’d struggled halfway out of the chair, ready to make a break for it, when the boys caught each other’s eye and burst into raucous cackles.

“Oh, my God, look at his face!” said Wellington. “He believed us!”

“He looks like he would hit us,” Jonas said.

“Or cry,” said Wellington.

Jonas mirthfully feigned some boo-hoo-hoos.

Wellington wrested the coconut from Jonas and thrust it toward me. “Take,” he said.

I wouldn’t. Still too rattled.

“We were only joking,” he said. “Treating you like a baiano!” He forced the coconut into my hands. “This is a gift, you see? A gift! For you, our friend.” He used the suffix that made the word mean big friend, true, good friend—not just an amigo, an amigão.

“Really?” I said.

“Yes, yes, of course,” insisted Jonas.

I smiled provisionally, trying to swallow the rest of my suspicions. “Okay, sorry,” I said. “Sorry, I understand.” I hated that I’d fallen for their gag, that I’d been ready to.

Wellington said, “Stay calm, okay? We want you here. Beleza!” He gripped my knee meaningfully, and let his hand remain.

My knee had never housed so many vivid, hopeful nerves. “Thank you for the gift,” I said. “I promise: I’ll stay calm.” But just as I said calm, I shook the coconut at him, splashing arcs of water on his cheek.

“Caralho!” he screamed, and jocularly tipped me out of the chair.

The coconut squirted loose and the three of us scrambled for it, tumbling together, knocking heads, each, in turn, on top. I thought I heard my shirt rip, or my khakis—who cared?

We wrestled on, our laughter fizzing like sparklers. All of us were panting, wet, rough with stuck-on sand. We smelled like a spill of suntan lotion.

When finally we all gave in, Jonas split the coconut, then cut off three thin chips of the husk to use as spoons. We gorged on the creamy, quivering meat.

“My first food of the day,” Jonas said. “I have such hunger!”

“Oh, my God, really?” I said. “Here, then. You should finish.”

“No,” said Wellington. “You are the guest, you eat as much as you like. Besides, I think he maybe lied. I think he ate a big, big piece of bread.”

At this, they both doubled over laughing again. Why? How could they find their deprivation funny?

Too self-conscious to eat any more, I handed Jonas my piece.

He pointed to my wedding band. “So,” he said, “she knows?”

“Who?” I said.

“Your wife! She knows you come to our tropical paradise with another woman?”

Smirking, I thought of the text Craig had sent the night before: Fucked any island studs yet? Pics or it didn’t happen!!! I could have tried to explain to these boys, but why—to open their eyes? Why was eye-opening always up to me? I shrugged and said, “We all have to have some secrets, no?”

“Or maybe she worries,” Wellington said, “not about Marisa. Maybe she worries you came here for the bread!”

Again their rollicking, incomprehensible laughs. I must have frowned.

“You know what bread is, right?” said Jonas.

“Pão? Of course,” I said.

“No, not pão,” said Wellington. “He asked do you know pau.”

“Spell it?” I said, and he did. I’d never seen the word. But how embarrassing—a beginner’s mistake—not to discern the nasalized diphthong.

Jonas scrounged around until he found a fallen mango branch, then snapped off a baseball bat-length stick. “This,” he said. “This, here, is a pau.”

“But also it means,” said Wellington. “It means, you know, this.” He hitched up the bottom of the left leg of his board shorts, and yanked out his fat, floppy cock.

“Oh!” I said, unable to look away.

I thought he’d tuck himself back in; instead he pinched his drooping foreskin and, as though taming a rowdy kitten by the scruff, started whapping his cock against his thigh.

Jonas, tittering, took my penlight and trained it on the action, making cheesy porno soundtrack noises.

Wellington retracted his foreskin, exposing the wet, pink head, which seemed like a separate, guileless creature. “Now you understand when I say pau?”

The way I heard it, I pictured a lights-out cartoon punch: POW!

A murmuring, then, in the nearby dark. Intruders? Just the wind?

“Vamos,” said Jonas. “Enough, okay? Wellington. Time to go.” He tossed me the penlight, took his machete and clippers, and hurried off.

Wellington stood up, languorously rearranging his shorts.

“Enough!” called Jonas again, behind a veil of leaves.

Wellington winked. “See you tomorrow,” he said, and loped away.

The next evening, when the kombi from the village dropped us off, Marisa started prancing down the sandy shortcut lane, swishing her golden ponytail like a semaphore. I called her back, told her we should probably go the long way, the cobbled road that rambled safely through the tourist district. “Heard there’s been some mischief by the shantytown,” I said.

All day, despite trying, I hadn’t been able to get Wellington out of my mind, but when I did find him, I didn’t want her with me. Not only because he might look right past me and ogle her. What if she tried to bond with me, giggling, poking my ribs: Oh my gosh, Carl, isn’t he just adorbs? How glaring, then: a pansy and his sidekick. I wanted Wellington still to see me as a man with a wife at home. A wife at home and a knockout girlfriend here. (It didn’t feel like closetedness but the opposite—a bracing liberation.)

We strolled to the town center, past dusty Internet cafés and faded stucco storefronts. A saggy-diapered girl kicked a volleyball half her size; beyond, a woman in a traditional lace bodice wanted us to pay to have our picture taken with her. You could see how, in better days, the place had been a draw. The old Dutch fort, its turrets shedding whitewash into the sea, the seventeenth-century church with a tree branching out of a belfry window.

As we skirted the central plaza, a wizened man accosted us. “Happy hour,” he said in English. “Three caipirinhas, price of one. Come.”

“Ooh ooh, let’s!” Marisa said with a convert’s overenthusiasm, still quite new at being an ex-Mormon.

I didn’t want to wait too long to hunt for Wellington, but maybe a little liquid courage wouldn’t be so bad. We followed the tout to his beachfront “bar”—a corrugated-tin roof atop four tottery wooden posts—where another old man served us caipirinhas.

I toasted Marisa. “Your first assignment—successful, thanks to you!”

“Aw, I bet you say that to all the gals.”

“No, I’m serious.” She’d softened the stubborn farmers as I had failed to, coaxing them at last to sign the loan. “Where’d you learn that kind of persuasion?” I asked. “They teach that on your mission?”

“Kidding?” she said. “In eighteen months, I didn’t make one convert.”

She tossed back her drink with a happy little hiccup. I downed mine, too, and called for another round.

“If only those folks could see me,” she said.

“Drinking the devil’s nectar?”

“Yeah, and with an open homo-sex-ual.”

A beefy shirtless vendor passed, hawking brazier-charred hunks of cheese. “Mm,” I said, inhaling the smell, and Marisa gave a throaty laugh—wanting, I guessed, to think I’d meant the man.

“My mission companions,” she said, “were these prissy, perfect girls, always trying to seem the most pious. I’m not sure I believed a word they said. And you do everything together, okay? Everything but in the bathroom. Even then, you’re always supposed to stay within earshot.”

“Yikes,” I said. “I had no idea.”

“Compared with that, this?” she said. “With you? What a relief! To do good stuff but honestly? With someone who’s just himself?”

The barman brought us a basket of tiny, sardine-like fried fish. “Local specialty. Pititinga,” he said. “Five reais.”

“Yum,” I said. “We’ll take them. And also two more drinks?” Then, when he’d gone: “So cheap! At home, that’s what—buck fifty, buck sixty?”

Marisa winced. “Sort of makes you feel like crap, right?”

“Maybe, sure,” I said. “But I always remember when Craig and I went down to Buenos Aires: economy tanking, desperate people selling scraps of cardboard. But four pesos to the dollar? We were rich. I said to one guy—we’d bought a hand-tied rug from him, for peanuts—I said I felt bad giving him so little for such nice work. Know what he said?”

Marisa turned her face hopefully toward me.

“He said, ‘My friend, something is always, always better than nothing.’” I swallowed a crispy pititinga—bones, tail, and all.

My third caipirinha came. I watched the big poached sun drip its yolk onto the sea, the fishing boats that bobbed like bathtub toys. I felt deliciously liquefied, ready to surge into the evening’s swift, uncharted stream.

Wellington. The River Wellington.

“I’ve been thinking,” Marisa said. “About the next assignment? Maybe the farmers here could make video testimonials, so when we get to Ecuador, the folks there will be able to see—”

“Shh,” I said. “Listen. The waves against those boats!”

Dutifully, she listened. Then: “So? What do you think?”

“Yeah,” I said. “Write up a proposal when we get back? For now though…” I drained my drink, and tapped my watch’s face.

“Oh?” she said. “Okay. Guess you’re right.”

I called for the bill, and left a tip as lavish as my hopes for what came next.

At the guesthouse, I kissed Marisa tipsily on both cheeks. “Ferry’s at ten tomorrow,” I said. “Taxi’ll come at nine.”

“Right, boss,” she said. “Straight to bed for me.”

“Me, too. We’ve earned our beauty rest!”

But as soon as I hit my room, I got busy.

First, I took the thumb drives I’d picked up in the village—the environmental adviser’s latest run-off guidelines, the site maps our agent had updated—and loaded the files onto my laptop. I emailed them to Briana, my admin assistant in Boston.

Antsy to get back into the night, I quickly cleaned myself—not a full-on shower, just a “ho bath,” as Craig called it: washcloth to my pits, neck, and crotch. I changed into my swim trunks, a sleeveless T-shirt, flip flops. Into the zippered pocket of the trunks I tucked a twenty (best to have something to give a robber), then locked my wallet and laptop in the safe.

I slipped out the back door, which led right onto the beach. The sky was clear, with a pale, swollen moon lighting the sandbar, where barefoot boys played two-on-two soccer. A lusty wind whipped up from the water. The alcohol in my veins should have made me crude and stumbly, but my body brimmed with a graceful equilibrium. My blood, my breath, the island air: all one balmy smoothness.

I clambered up the path to the road, pulling on arm-thick vines, and came out on the sandy lane, a quick uphill to the rendezvous. That was the word I sang in my head; it sounded urgent, epic. A rendezvous with a racy island boy.

I passed the last inhabited house, its ghostlike laundry dancing. A guard dog growled enviously at the end of a rusty chain. Turning onto the jungly trail, I strained for Wellington’s psst.

Nothing. I kept padding forward.

Here was the palm tree, and here the wobbly yellow haircut chair, but in it rested Jonas, just Jonas. Head thrown back, hands conducting a tune in his own mind.

“Oi,” I called. “Oi, Jonas.”

He twitched to attention, jolting up, and dumped something behind him. Then he sprang a step too close and crushed my hand in his. “Oh, how good! Carl!” he said. “My brother.” His breath smelled strange, singed, artificially sweet.

“Wellington here?” I asked.

He shrugged. “I am here.”

“Yes, but—”

“What? I am not sufficient? You do not like me?” His fleshy, big-browed face looked ready to crumple.

“No, it’s not—no,” I said. “It’s just…I came for Wellington.”

He sat back in the chair, pouty and inscrutable, but couldn’t seem to keep his legs from jittering. He jumped back up, told me to sit, then hovered hawkishly near. The too-sweet chemical smell was now stronger, all around me. Looking down, I traced the stink to an empty soda can: hole in its side, scrap of scorched tin foil at the top.

Jonas tore a mango from a nearby tree and bit it, ripping off some rind he spat away. He sucked the fruit—nursed it, really, impatient as an infant. “Look at all I have,” he said. “Just mangoes. Just green mangoes.” He thrust the unripe fruit before my eyes.

“You’re hungry,” I said. “I’m sorry. That’s awful.”

“Yes,” he said. “Maybe you have a few reais for me?”

I looked into the gloom of the dense, unyielding woods. “Let’s walk into town,” I said. “I’ll buy some food, okay?” I stood, took a step toward the lane.

“No, no. You want to wait for Wellington, I know. Give me the money. I can buy the food.”

“I’m not giving you money,” I said, eyeing his makeshift crack pipe. “We’ll get some food. Some fish? Maybe pizza?”

“Porra!” he swore. He hurled the half-eaten mango at my feet.

I staggered back, straight into Wellington. How had he approached so quietly?

“Careful,” he said. “Careful, amigão. Are you drunk?”

“No,” I said, and all of a sudden I didn’t think I was. His fingers set off flares along my sweaty shoulders’ skin. I tasted the limey bite of his cologne.

“Good,” he said. “I hope you have a lot of”—he winked—“energy.” He wore the same ratty, red board shorts as yesterday. Sweat lightly stippled his bare chest. “Maybe you want to walk to the beach with me?” he said.

“Yes!” I said too quickly, unable to look Jonas in the eye. He had sat back down in the feeble yellow chair, arms crossed, scratching his elbows with bleak abandon.

“I am taking our friend to the beach,” Wellington proclaimed, as if repeating news for the hard of hearing.

Grumbling a curse under his breath, Jonas tipped his head back, resuming the pose I’d found him in before.

Wellington led me down the trail, gingerly through the leafy-smelling dimness. We turned onto the sandy lane, toward the ocean’s roar. The moonlight magnified him with an incandescent aura. It looked as though a touch from him might shock.

I raced ahead—away from the fog of guilt that seeped from Jonas—but Wellington lagged. “Calm,” he said. “More slowly.”

I eased my pace, and Wellington, in turn, slowed even more. He told me he was sorry for being gone when I’d arrived. “I wanted to smell fresh,” he said, “but I had no perfume. I had to go and borrow from a friend.”

“Nice,” I said. “I smelled it right away.”

“No, to really smell, you must be closer,” he said. “Here.” Grabbing my wrist, he pulled me to a halt, then into a hug. He guided my head to bury my face into his wiry neck. I took the chance to sniff for any singed hint of crack, but thank God, no, the scent was like a just-cleaned hotel room.

A sudden thudding, like hoofbeats, too fast for me to flee.

A jolt—a jagged blow—into my back.

I tore myself from Wellington, and I was facing Jonas, his eyes sparking madly in the moonshine.

“Give me your money. Now!” he screamed. “Everything. Give it to me.”

He raised his hand, and I could see the glint of the machete. He held it cocked, his arm flexing, the blade like a beast he had to bridle.

“Come on,” he said. “Be smart. Give it all.”

My body throbbed—not just where he’d jabbed, in every cell.

Stepping back, Wellington stared blankly into the distance. Why the fuck was he standing there not helping?

Jonas jerked his arm. The sleek machete lurched.

Twenty reais. Less than what I’d paid at the beachfront bar. If he were a stranger, a garden-variety thief, I would have caved. But now I was shouting: “I tried to help. I wanted to. I wanted!” In Portuguese, I couldn’t describe my mournful anger’s shape. Maybe in English I’d have done no better. “I tried,” I said. “And this is how you treat me?”

Jonas glared and set his jaw. Wellington still said nothing.

“Like this?” I yelled at Jonas, and lunged in his direction. “Fine,” I said. “Then cut me. Cut me, if you want.” I thrust my arms out, palms up, exposing my pallid wrists.

He pumped his arm, and I turned my face, bracing for the gash, but Wellington leapt between us. He thwacked Jonas’s ear.

“Beat it,” he said. “Idiot! Go away!”

Jonas’s hand fell to his side. The blade bit into the sand. He seemed about to snarl something, but Wellington shot him a brutal look. He spat and sped away into the night.

I should have been shaken, but all I felt was thrumming thrill, relief. “Thank you,” I said to Wellington. I clutched his neck. “Thanks!”

I couldn’t think. I was almost concussed with giddiness. “Come on,” I said, tugging him forward, breakneck down the path.

He stopped. “The beach is that way.”

“No,” I said, “my guesthouse,” fearing that if we stayed out here Jonas might come back.

Wellington twisted his toes in the sand. “Maybe we should try instead tomorrow?”

“I leave in the morning,” I said. “You’re worried about the owner?” Kids like him were regularly hassled by local merchants. “It’s fine,” I said. “You’re with me.”

“And your ‘friend’?”

“Asleep,” I said. “In her own room. Let’s go!”

Everything now seemed to unspool in double time: our dash down the path, my fumble with the sticky guesthouse key. We tiptoed through the shadowy hall, past the muffled Globo newscast coming from the office.

Inside my room, we hopped around, bonded by a silly, monkeyish sense of disobedience. My lungs thumped. My pulsing hands and feet felt fattened, potent. I was drunk again but not on booze, on near-escape and sneakiness and sharp anticipation.

I pushed him down to the bed, but he bounded right back up. “Like this,” he said, and pressed my shoulders until I knelt below him.

When I yanked his shorts, the Velcro fly gave way with a crunching rip. His cock was hard and curved, the color of kiln-baked clay. It had the look of an ancient tool unearthed by archaeologists. I wanted him to dig with it inside me.

I pressed my face into the smother of cheap perfume. I was touched to think of him primping, dousing these parts for me, to cover up his smell of poverty: sweat and grime and palm oil, the faintest trace of piss.

“Go on,” he said, pinching my jaw open. With a laborer’s deft efficiency, he filled me in one stab. I loved the way he handled me, thumbs hard at my ears, as though I were a tricky apparatus that needed steering. Clapping his fingers tighter, he made a high, uncertain sound, and needled the back of my throat with warm spurts.

He had lasted maybe sixty seconds.

I wasn’t disappointed; if anything, I was all the more turned on. How honest and uncomplicated his sprint to gratification! How flagrantly he took just what he wanted!

“And me?” I said, getting up.

“Fine,” he said. “No problem.” But he just stood there, noodling with his foreskin.

I opened my shorts and started stroking, abashed but also goaded by his aloofness. He watched with what seemed a kind of professional curiosity, a craftsman comparing methods of production. After a few minutes, he said, “Why does it take so long?” I made a stricken face, and he added, in a tempered voice, “If you like, okay, you can touch.”

His cock still drooped from his fly, dramatically flabby, languid, but what I yearned to touch was his hair: the bristles of his one-day-old crew cut. I reached up and rubbed my palm against its rough preciseness, and in another instant I was done.

We fixed our clothes, I wiped the floor, we took turns in the bathroom. I figured he might hurry off, but he dawdled, fingering the carefully rustic furniture, and finally sat firmly on the bed.

“I think I still want something,” he said.

“Wow,” I said. “Already?” At his age, I guessed, he was raring to go back at it; at mine, I was done…but I could certainly get on my knees again.

“Normally, in the evening,” he said, “I sell popsicles. At the plaza.”

I waited for him to go on, but he just stared, hands on hips, as though he’d clinched an irrefutable case. “Okay, um…popsicles?” I said.

“Yes,” he said, “but tonight—tonight I was only with you. Understand? And so I earned nothing.”

“Oh,” I said. “Oh!” I felt as suddenly foolish as the hollow sound I bleated. “But you never,” I said. “I mean, I thought…” What? What had I thought?

“A whole night,” he said, shaking his finger. “Because of you.”

Thunderheads of shame and anger gathered in the distance, but I felt myself willing up a wind to ward them off. I liked Wellington’s pluck. He’d saved me from Jonas; I owed him. Plus, if I gave him something, it wouldn’t quite be for sex—more like compensation for his opportunity cost. That was the concept he’d pitched to me, even if he couldn’t name it, and I was tickled to think how well he might succeed in b-school. Shouldn’t the kid’s entrepreneurial gumption count for something?

“Here,” I said, unzipping my pocket. I handed him a bill.

“Twenty?” he said. He crumpled it in his fist. “Twenty is little.”

“It’s all I have.”

He snorted.

“Really, you can check,” I said. I tapped my hips, permission for a pat-down.

“You must have more somewhere,” he said.

“Told you, we leave tomorrow. I already got rid of my reais.”

Now he stood. His face was measurably hardened.

I doubted he’d be violent; he knew I could summon the owner. But I felt shitty for fibbing. (Of course I had more cash. My wallet, in the safe, was thick with dollars.) Also, I wanted our interaction not to end like this—as confirmation, for each of us, of our worst preconceptions.

“Look,” I said, “I wanted to ask. About what happened before. Is Jonas actually hungry? Or does he just want money to buy crack?”

He looked as though he wanted to slap the question from my mouth. “I work,” he said. “I earn. You saw me take drugs? No.”

“No, of course, I wasn’t saying…I’m asking about Jonas.”

“Is Jonas hungry? Of course.” He poked his belly. “We all are.”

“In that case, I’m happy to get some food for him,” I said. “I meant it before. Maybe you’d like some, too?”

Appraisingly, he eyed me. “Food?” he asked. “From where?”

“From here. They’ll never miss it.”

Now he grinned—grateful, of course, but also somehow impish. Maybe he liked the thought of pulling a fast one on the owner. “If you would like to give,” he said, “then yes.”

“Quiet,” I said, and motioned for him to follow.

We skulked down to the breakfast room—a stale smell of coffee grounds, crumbs—and I rooted in the cabinet for a trash bag. Wellington watched as I filled the bag with fruit from the sideboard’s bowl. A big papaya, bananas, two handfuls of pitangas. When I tossed in some individual boxes of Sucrilhos, the Brazilian version of Frosted Flakes, I saw Wellington’s grin go wide again.

I was beaming, too, with righteous, Robin Hoodish satisfaction. What a night! We’d come so close to disaster, but here I’d found a way that we all could end up contented. My heart bulged with leniency—for Wellington and for Jonas, for myself.

Last, I grabbed a couple of rolls, baked by the guesthouse cook—from yesterday, but surely fresh enough.

“Perfect,” Wellington jested. “You know how much I like to eat bread.”

“Here in Bahia,” I said with a purposely bad accent, “they say the pau is very, very tasty.” I handed him the ample goody bag.

I hoped he might come back to my room—another minute, at least!—now that things were good again between us, but he scuffled out to the hallway, toward the door. He seemed edgy—embarrassed, I supposed, by his own neediness, the proof of which now dangled from his hand. “Thanks,” he said. “I will bring this right away to Jonas.”

“Awesome,” I said. “Glad it all worked out.”

He offered me a fist bump, then seemed to reconsider, and clasped me in a masculine, endearingly chaste hug. “My brother!” he said. “Your wife is a very lucky woman. I hope you get home safe to her, and happy.”

When he nudged the door open, I softly said goodbye.

“No,” he whispered. “We never say ‘goodbye.’ Say ‘See you later.’”

“Right,” I said. “Better. See you later!”

But he may not have heard me, he ran off so fast.

I shut the door, smelling him still, his evergreen cologne. I moseyed back to my room, drained but also restored, and minutes later was sprawled in bed, ready to dream brilliant, easy dreams.

The taxi was outside, idling, when Vagner, the guesthouse owner, appeared in my doorway, breathless.

“Just a sec,” I told him. “One more bag to zip.”

Vagner nodded but held his ground. He narrowed his dismal eyes. “Local boy’s out front,” he said. “Claims he found something of yours on the lane.”

Found something? But what could I have lost?

Maybe Wellington had decided to give me his contact info, and needed a pretext to get past the owner. Or Jonas. It could be Jonas, apologizing.

“All right,” I said. “Thanks. I’ll go see him.”

“I’ll go with you,” said Vagner. “You know they can be dangerous.”

“No, no, please,” I said. “I’ll handle this on my own.”

With disapproving huffs, he trailed me down the hall, and finally said, “You’ll speak outside. I’ll be at the door.”

Wellington stood mildly in the stinging morning sun. He wore a Chicago Bulls cap, a tank top reading, in glittered letters, Street Wear—his version of dressed up, I imagined. My throat filled with the memory of last night.

“Good day, Senhor,” he greeted me with stagey, clipped refinement.

“What a pleasant surprise,” I said. “Didn’t think I’d get to see you again.”

“Yes,” he said. “I think we have some business.” He shifted his shoulders, a combination of skittishness and defiance. “I found these on the lane,” he said, holding out his palm, in which were balanced two black-plastic thumb drives.

But no, I thought, those couldn’t be mine, I had mine in my room last night, and—

“Oh?” I said with trumped-up calm, conscious of Vagner behind me.

Wellington flashed his same old impish grin—the little phony! In the breakfast room, and afterward, as we hugged: he’d had the drives.

“I thought maybe you would like to give a reward,” he said. “For finding them. Bringing them back to you.”

“Really?” I said. “A reward?” I stared at his open palm. Did he think my very dignity was for sale? “But no,” I said. “I don’t think they’re mine.”

He looked confused, his eyes a blur. High as fuck, no doubt. “Yes, Senhor,” he said. “I know these things are yours.”

“How?” I said.

“You know how.” A mocking, slow-motion wink.

To make a joke of my sympathy! To scoff at what I’d thought had been humane! “Why would you do it?” I said. “Did I hurt you? Did I steal anything of yours?”

Wellington shuffled back a step. He clenched his fist on the thumb drives.

“In my own country, you know, I’m not dumb,” I said. “I’m smart. I help people. That’s what I do. I help.” The words came out weaker than I’d wanted, and so, to toughen them, I jabbed a knuckle into Wellington’s sternum.

He leaned into me, as if he liked the pain. “In your country, of course,” he said, “your life is very nice. A very beautiful, normal life—you want to keep it, yes? That is why I think you will buy these things from me.”

“Buy what?” I heard, and turned to see Marisa with her suitcase. “My Portuguese,” she apologized. “I couldn’t catch it all.”

Vagner had come out with her, clutching a phone like a shiv. “Pay him,” he said. “That’s the way things work here, understand?”

“Wait, you know this kid?” she said. “You took something of his?”

“Jesus, no. He took something of mine. He stole my thumb drives.”

“But why was he…what were you even—”

“You made a mistake,” said Vagner. “Pay the boy. We don’t want any trouble.”

“Fine,” I said to Wellington. “Let me see those drives.”

“Money,” he said. “You have to give me money.”

“Yes, but first I have to see you haven’t damaged them. I have to make sure they’re in good shape.”

Churlishly, as if he were conferring a big favor, he dumped the drives into my hand. I didn’t even look. I flung them to the ground. Then I stomped and stomped again. The pop of cracking plastic. I crushed the shards beneath my twisting heel.

Wellington’s bony shoulder flinched, but he snickered, tossed his chin. “Look,” he said. “Look, I have this, too.” From his shorts he pulled a luggage tag, then waved it at my face. “Your address, see? Your number. I could call your wife and tell her all we did together. Your wife—would she like to hear all that?”

Marisa stared, steely. “Your wife? Did he say wife? What kind of lies—”

“We’re late,” I said. “Get in the taxi. Now.”

Then, to Vagner: “Call the police. Tell them he’s a thief.”

When Vagner started to dial the phone, Wellington spun and ran. His feet slapped and slapped against the sand.

Marisa, in the hurtling car, sat cross-armed. “What the hell?”

“Please,” I said. “Can we just get out of here?”

“But what about…what about the thumb drives?”

“Sent the files to Briana,” I said. “Everything’s all backed up.”

“Ah, of course.” She smiled tightly. “I get it. No harm, no foul.”

“Forget it,” I said. “That’s what I plan to do.”

With a lash of her sun-bleached ponytail, she turned her back on me. “But the kid,” she said in a sharp, low voice. “Surely you gave him something? I mean, something’s always better than nothing.”

I stared out the window at the blear of passing palms. My left heel, the one I’d used to smash the drives, was sore. I couldn’t shake the feeling of something stuck beneath it. I checked and checked but couldn’t find a thing.