fruit to color their bodies. It is also used in the cooking. The urucum is a shrub or small tree

originating from tropical regions of the Americas. It has long been used by American Indians

to make body paint, especially for the lips, thus earning the nickname of “lipstick tree.”

Brazil. 2009. Photograph by Sebastião SALGADO/Amazonas images. Courtesy of TASCHEN

The force that through the green fuse drives the flower

Drives my green age; that blasts the roots of trees

Is my destroyer.

And I am dumb to tell the crooked rose

My youth is bent by the same wintry fever.

—Dylan Thomas

Over the past four decades or so, Sebastião Salgado has solidified into an international treasure of sorts, as one of the world’s most eloquent and flinch-resistant documenters of the doleful human condition. War and deprivation, death and disease, rootlessness and repression loom large among the Brazilian-born photographer’s themes of choice, and even as his black-and-white imagery protests the devastating inequities of modern geopolitics, something about it—the drama, the scale—propels the work beyond this moment.

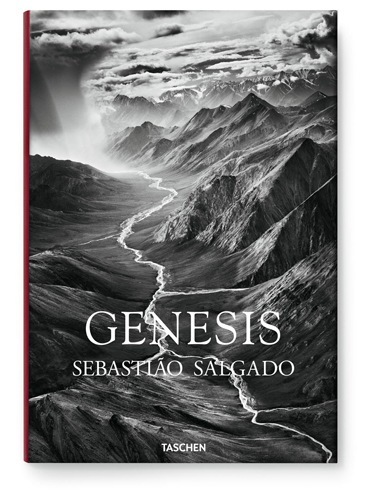

Salgado does not work in half-measures; indeed, the tone and scope of his photography collections can be overwhelming. Genesis, his latest (and perhaps ultimate) release on this grand scale, is no exception. But it avoids the most dispiriting elements of his other work, instead celebrating “the beauty of nature across the globe,” as his wife and co-producer, Lélia Wanick Salgado, explains in the foreword to the collection. Salgado (now seventy-one) shot it between 2004 and 2011, during which time he made the switch from film to digital. The Salgados have described the photos of volcanoes, rainforests, hunter-gatherer societies, and so on, as a “call to arms” for conservation, and positioned them as a companion project of sorts with the Instituto Terra, the ambitious rainforest-rehabilitation organization that they have been operating since 1998 in the eastern state of Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Like Salgado’s photos themselves, the film is breathtaking. It is also an implied rebuttal to Susan Sontag’s castigation of Salgado as “a photographer who specializes in world misery.”

There are plenty of high-level endorsements, including praise from the director-general of UNESCO in the nearly nine-pound book released by Taschen last fall. But the greatest extender of what one hopes will be a very long tail might well be the recent documentary about Salgado, The Salt of the Earth, co-directed by his son, Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, and Wim Wenders. The film earned a special prize at Cannes and an Oscar nomination, following a limited qualifying run in December. It entered American theaters for real on March 27.

Photo by Thierry Pouffary, courtesy of Thierry Pouffary/Sony Pictures Classics.

Like Salgado’s photos themselves, the film is breathtaking. It is also an implied rebuttal to Susan Sontag’s castigation of Salgado, in a contentious 2002 New Yorker article, as “a photographer who specializes in world misery.” A need for redemption factors into Salgado’s personal story as well, and the filmmakers are right to exploit it for narrative effect, even if they tend to downplay the Christian undertones in both Salgado’s life and work.

Salgado, who has long borne witness to the human and environmental carnage of the Anthropocene moment, has declared that a goal of Genesis is to help preserve the “unspoiled world.” It may or may not do that. The Salt of the Earth, in making a compelling character of Salgado and framing his arrival as a conservationist as a loosely Christian parable, goes further toward achieving that end. What the film does not do, though, is address the contradiction inherent in Salgado’s unlikely adventure: that a photographer, of all people, should seek to dismantle the barriers that man has erected between himself and nature.

THE GENESIS OF GENESIS

Salgado, the film makes clear, arrived at Genesis after experiencing a loss of faith. Among other geopolitical horrors of the nineties, he had photographed genocides in Rwanda and the Balkans. His lens had been scorched by the burning oil fields left in the wake of the First Gulf War. “I no longer believed in anything, in any salvation for the human species,” he explains in the film, his voice wavering.

Ultimately, a conservation initiative would renew that faith. Salgado returned to the cattle ranch in Brazil on which he’d grown up. His father’s clearing of the rainforest there had helped provide for his son’s education and allowed Salgado to go to Paris, where he decided to give up a career in economics and become a photographer instead. While he was busy making a name for himself abroad, Salgado’s father’s proud livelihood was sucking the family estate dry. Plants withered, wildlife vanished, and the rivers filled with sand. Salgado and Lélia were determined—against his father’s incomprehension—to restore it. Since then, they have planted millions of new trees, a flowering that has brought back water and wildlife and made the 17,000-acre Instituto Terra a benchmark reforestation project in Brazil and beyond.

The success of the Instituto Terra inspired an artistic change of heart in Salgado. Originally conceived as an indictment of man’s environmental carelessness, Genesis became something else. “I followed a romantic dream,” he explains in the foreword to the Taschen book, “to find—and share—a pristine world that all too often is beyond our eyes and reach.”

Puilanga Lake near their village. The Upper Xingu Basin is home to an ethnically diverse

population, with the 2,500 inhabitants of thirteen villages speaking languages with distinct Carib, Tupi, and Arawak roots. While they occupy different territories and preserve their own cultural identities, they coexist in peace. Brazil. 2005. Photograph by Sebastião SALGADO/Amazonas images. Courtesy of TASCHEN

Salgado locates that world in remote and ancient landscapes: wrinkled glaciers of the Arctic Circle, Jurassic-looking plants of Uganda and Rwanda, flowing outlines of sandbars on the Madagascar coast that resemble original matter awaiting form. A caiman pokes its head out of dark waters to eye Salgado’s lens, his slow gaze like some very old and basic awareness emerging from the ooze. There is a recurring motif of veins, or arteries, expressed in images of rivers from above, of intersecting ravines and lava flows, networks of tree branches, and even the taut sinews of Yali tribesmen in the Papua Indonesian highlands.

Salgado visited some thirty-two countries or regions over eight years, and made nine trips to Africa alone. There is an old-fashioned pursuit of the sublime fueling his “romantic dream,” but also a less-than-romantic impulse to catalogue the results. The photos are ordered by ecosystem, beginning (in encyclopedic fashion) with Antarctica. In a nod to Linnaeus, the wildlife photos provide the Latin species name. We are, in other words, very much on the intellectual-artistic continuum that leads backwards from the Enlightenment to the Old Testament—and therefore critically removed from the non-human world. As long ago as the Book of Genesis, taxonomy has pried a gap between man and other beings. “And the man gave names to all cattle and to the birds of the air and to every beast of the field; but Adam had no one like himself as a help” (2:20).

Salgado’s work serves a containing function of a different, but related, sort. As Sontag noted in On Photography, it is in the nature of the camera to do so. “By disclosing the thingness of human beings, the humanness of things, photography transforms reality into a tautology.” Salgado’s images are not mere diagrams, of course, any more than Dylan Thomas’s lines about his inability to commiserate with the “crooked rose” belong in a botany textbook. They are easy to argue for as art, even if Salgado himself resists the label. But that doesn’t mean they achieve everything he might like them to. The flattening effects of an enormous photographic project, to cite just one example, would seem to negate Genesis as a celebration of the planet’s biodiversity and uniquely valuable tribal cultures.

Salgado’s pictures of cloaked goatherds in the Ethiopian highlands, of sunlight beaming through clouds, draw on age-old determinations of what is holy and good.

In the foreword, Salgado explains how the regeneration of his family’s estate altered his perspective on human society. “Marveling at nature’s ability to restore itself, we grew more anxious about the fate of the planet at large. We understood the absurdity of the idea that nature and humanity can somehow be separated,” he writes. Humanity must reconsider its exploitation of the natural world, no doubt. But is it helpful to imagine, even with noble ends in mind, that we might one day not be separated from nature? Genesis itself is a testament to how distant a fantasy this is.

Where to start? Salgado’s images, for one thing, lie comfortably within the tradition of Western art. They teem with Christian tropes in particular. A San woman in southern Africa peeks out from underneath a grass head covering with the modesty of a Virgin Mary. Salgado’s pictures of cloaked goatherds in the Ethiopian highlands, of sunlight beaming through clouds, draw on age-old determinations of what is holy and good. It almost goes without saying that Eden is everywhere; Genesis swells with remorse for paradise lost as powerfully as hellfire burns through Salgado’s photographs of Kuwait’s oil fields.

There, however, he had oil-drenched firefighters to occupy his frame. Salgado’s turn, in Genesis, away (for the most part) from human subjects and toward landscapes and wildlife, alters the equation. It also aligns with a significant change in Salgado’s thinking, as he explained in an interview with the Aperture Foundation’s blog:

The last point is, alas, too true. Take Salgado’s two wonderful photos of leopards, for example. One stares at the camera, crouched against an enveloping backdrop of inky night; the other, sitting over a kill, gazes off frame with a distinctly feline combination of impassivity and alertness. I feel drawn to these images. But while they activate my own thoughts and feelings about leopards—indeed, this is part of their intense appeal—do they truly reveal anything about what the leopard may think about me? Or about anything else?

As Salgado’s claim suggests, the real avenues for meaning—that is, the ones we can truly traffic in words and images—operate within our own species. This is where The Salt of the Earth comes in.

DESERTS AND FORESTS

Rather than tell Salgado’s whole story, as The Salt of the Earth does, the film could have started with him and Lélia moving back home. “It might have been an interesting story to make about someone who was the first, after God, to replant the Atlantic rainforest, because nobody had done that before,” Wenders explained when I asked him. “But it was so much more interesting when you understand the family history: the sins of the father, who meant well but didn’t really understand that he was responsible for the decline of the land. Like his entire generation, they took down forests as if there was no tomorrow, thinking it was in the name of progress.”

The documentary (aided by Laurent Petitgand’s wonderful score) dramatizes that decline with sweeping effectiveness. In the film, which was shot shortly before his death, Salgado’s father seems incapable of linking the degradation of his ranch to the ranching itself. Plagued by drought and erosion, the land evokes the environments of suffering that Salgado has photographed so powerfully elsewhere.

The film tunes in here to the theme of desertification. In his superb study, Forests: The Shadow of Civilization, Robert Pogue Harrison puts this baleful ecological phenomenon in a spiritual context, noting how Nietzsche, Beckett, and Eliot imagined barren landscapes as those most appropriate for a society that has lost touch with the “originary plenitude” of divinity. “If desertification occurs within, the forests cannot survive without. Soul and habitat…are correlates of one another,” Harrison concludes. The divine still holds out in the forests, like some embattled guerrilla faction, but only as a shadowy and half-acknowledged counterpart to those newer, hegemonic gods of the sky and city. (Meanwhile, we might wonder at how the excesses of contemporary belief systems tend to find their most vivid expression in the desert. Note the shriveling of the Aral Sea, a result of thoughtless Soviet irrigation practices, and the desert backdrops in ISIS beheading videos. Note Las Vegas.) Viewed this way, conservation efforts that prioritize wildlife over habitat are beside the point.

The Instituto Terra, to its credit, begins with the land. More admirable yet, the replanting that has sparked new life in a valley the size of New York State has kept certain essential forest mysteries intact. “Nobody knows how the jaguars came back,” Wenders marveled when we spoke. “Nobody re-wilded them. And they didn’t plan for all these birds to come back—they came on their own. A lot of the animals show up if their home plants are back, and you have to understand a lot of the birds and insects are linked to very special trees. Even the little crocodiles, nobody knows how they made it, but they’re there. It’s almost a fairy tale.”

THE POWER OF THE PARABLE

For all the empathy it reveals in Salgado, the film only scratches the surface of his beliefs. Those beliefs are an interesting mix. On the one hand, Salgado is a world-weary man of reason. The first trip he took for Genesis followed Darwin’s footsteps, and Wenders explains in his voiceover narration that Salgado’s training as an economist gave him an understanding—unique, perhaps, among his contemporaries—of the global forces behind his subject matter.

Without fully acknowledging it, the film makes faith—and its loss—a central theme.

Salgado is not a practicing Christian. Juliano, when we discussed it, explained that he had been baptized against his father’s wishes. But that’s not the end of the story. Salgado’s images often ended up in church publications, a fact the film does not mention. His Marxist convictions did nothing to preclude his participation in a group like JUC, or Catholic University Youth, which the film does touch on; it also alludes to the priests who served as his guides to the continent’s impoverished rural regions in the seventies. Shielded from brutal reprisals in a way that secular union leaders were not, these clergymen (as the film notes) brought “liberation theology” to Latin America’s working class.

Without fully acknowledging it, the film makes faith—and its loss—a central theme. Its title alludes to a line from the Book of Matthew that deals with this very question: “You are the salt of the earth; but if the salt has become tasteless, how can it be made salty again? It is no longer good for anything, except to be thrown out and trampled under foot by men” (5:13). The sense of purposelessness Salgado felt, the doubt that there was “salvation for the human species,” is what motivated him to turn a desert back into a forest. We might also note that in many interpretations of these verses, the implied (and inferior) alternative to salt is sand.

The film tells a multi-generational tale of sin and redemption. That same framework emerges on another level, too, if one reads the Instituto Terra and Genesis projects as a joint response to the backlash Salgado faced around the turn of the millennium for his war images. Critics began to question the morality of finding beauty in the suffering of the powerless, and the scope and visibility of Salgado’s work made him a primary target. Of Migrations, Sontag wrote:

“Taken in thirty-nine countries, Salgado’s migration pictures group together, under this single heading, a host of different causes and kinds of distress. Making suffering loom larger, by globalizing it, may spur people to feel they ought to ‘care’ more. It also invites them to feel that the sufferings and misfortunes are too vast, too irrevocable, too epic to be much changed by any local political intervention. With a subject conceived on this scale, compassion can only flounder—and make abstract.”

Wenders has defended Salgado, at least on aesthetic grounds: “When you photograph poverty and suffering, you have to give a certain dignity to your subject, and avoid slipping into voyeurism.” The film ignores the question, and its absence led to a tepid review from A.O. Scott in the New York Times. But it’s possible that Salgado himself internalized the critique. While Genesis is, if anything, more “epic” than his previous work, it eschews the subject of suffering, and is very much attached—almost as a promotional arm—to a local “intervention.” Redemption plays into this story, too.

OUTSIDE EDEN

As an investigation of the historical overlap of conservation and Western thought, Harrison’s Forests is essential reading. (It is also my source for the Dylan Thomas quote at the beginning of this piece.) The book traces man’s deeply ambivalent attitude to wild places, from Gilgamesh and Plato to nostalgic nineteenth-century English poets to Henry David Thoreau and Frank Lloyd Wright, with their hopeful experiments in post-Enlightenment forest-dwelling.

even daytime temperatures low. When the weather is particularly hostile, the Nenets may spend several days in the same place, with their reindeer, doing repair work on sledges and reindeer skins to keep busy. The deeper they move into the Arctic Circle, the less vegetation is to be found. Inside the Arctic Circle. Yamal peninsula, Siberia. 2011. Photograph by Sebastião SALGADO/Amazonas images. Courtesy of TASCHEN

Forests are “the story of human outsideness,” Harrison writes. “Because we exist first and foremost outside of ourselves…the history of forests in the Western imagination turns into the story of our self-dispossession.” Photography is perhaps the contemporary expression of this distance. Not that every culture or individual feels this separation, or attempts to bridge it with photographs, in equal amounts. In The Salt of the Earth, Salgado recounts that the forest-dwelling Zo’é people of the Amazon have a “perfect consciousness” that he is making images of them. They just quickly tire of it; to them, Salgado’s machete (which the Brazilian government forbids him from giving to them) is much more interesting. It is a very useful tool, and the camera isn’t.

Clearly, Salgado doesn’t share this belief. (Nor, for that matter, does Wenders.) But he overreaches if he thinks the camera will move us anywhere but away from the “huge equilibrium.” That is not to discount the services it can provide to efforts like the Instituto Terra.

In a joint statement, the Salgados write: “We must act now to preserve land and seascapes and protect the natural sanctuaries of ancient peoples and animals. And we can go further: we can try to reverse the damage we have done.” Violation, atonement. More than Salgado’s photos, Salt of the Earth spotlights the deeds required to bring back the birds and crocodiles, and the human stories behind those deeds that make them real. Embedded in this story are crucial fragments of a lapsed faith. This, in short, is the nature of our inevitable life on the outside—or, perhaps more precisely, the best version of it that we can hope for.

The Salt of the Earth is currently playing in New York and Los Angeles.

Darrell Hartman is a writer based in New York and the editor/co-founder of the website Jungles in Paris.

To contact Guernica or Darrell Hartman, please write here.