It’s a brisk October day in 1975. I’m 24, driving through Central Park with Gabriel García Márquez. As we wend our way through the park, and exit on Central Park West, I am utterly dumbstruck, afraid I’ll say something stupid to the man whose work, more than any other’s, inspired me to become a writer of fiction. García Márquez today, it hardly bears repeating, is secure in his reputation as one of the great writers of our time. He is the author of 100 Years of Solitude, which has sold 30 million copies in 35 languages; a new genre, magical realism, was spawned by this work. His bestselling Love in the Time of Cholera has been turned into a film, which opens this week in theaters. And he received the Nobel Prize for Literature, of course, in 1982. But in 1975, he is simply my idol.

We ride on in silence through the fall, sinking deep into the black seat of our Checker cab. Perhaps sensing my awe of him, he finally asks where I’m from. All I can mutter, barely audibly I’m sure, is the word Guatemala; this doesn’t seem to register with him, however, as he seems lost in thought, looking out the cab window at the tenement buildings as we drive uphill from Columbus to Amsterdam Avenue. Finally, on 109th Street, I edge up in my seat and venture to converse with him: “I live in this tan building. On the third floor.”

Hardly a response from him.

Aware of his own humble origins, I continue, “It’s a railroad flat, but the bathroom is new and the toilet is elevated like a throne.” Then I laugh at my own description of the john.

García Márquez nods disinterestedly, and I am stuck, frozen, frustrated in my fantasies of the writer’s life, of the opportunity it represents to meet a man as legendary as this, a living Hemingway or a Fidel Castro of letters. During this cab ride with my idol (whom I have been asked to guide through New York) I cannot know, of course, that, while, yes, my youthful illusions may yet need to give in a bit to the realities of the world, a collaboration of sorts is forming—if not a friendship then at least a thread between us that will culminate in my arriving in the strange position of being Gabriel García Márquez’s ghostwriter, and later bearing bad tidings to him at a time when he would be facing his own mortality.

* * *

I first encountered Gabriel García Márquez’s work in 1971; I was twenty. I pulled out his El coronel no tiene quien le escriba from my cousin Patricia’s bookcase in Guatemala City and read it in one sitting. It was the first book I read cover to cover in Spanish. This, for me, was an achievement—though I had been born in Guatemala, my parents immigrated to the States (Hialeah, Florida) when I was four. By the time I was eight, I barely remembered one hundred words of Spanish. Leaving Guatemala had orphaned me from the language of my childhood, which retreated from my mind like the damp Hialeah morning mist; it became the language of my memories, increasingly dusty and cobwebbed.

García Márquez changed that. From the opening page I loved El coronel for its subtle humor, its lean and spare language, the sense of comic absurdity—Roosters wear out if you look at them too much and We’re too old to believe in a Messiah. I gobbled up García Márquez’s subsequent novels, but that one stands out for most having helped forge my identity as a Latin American native and writer: “The rain is different from this window,” he said. “It’s as if it were raining in another town.”

Up till then, I’d been a huge fan of John Steinbeck’s 1930s novels (To a God Unknown, In Dubious Battle; The Grapes of Wrath), big books that matched García Márquez’s in breadth and human compassion, but that were linear, ploddingly narrative and without surprises. García Márquez was Latin America’s Samuel Beckett in his humor and depiction of an oppressive world, but while the latter was minimal, pessimistic and stark, García Márquez’s work was earthy, sympathetic to his characters and profoundly human. And his books embodied a leftist political consciousness that was immensely appealing to me. I had finally found a writer I could embrace.

In 1973, I began the MFA Writing Program at Columbia University, focusing, at first, on poetry. I was 22 and longed to be a successful poet, but at Columbia it often felt like I was writing in the dark. Ostensibly, I was another Columbia University silk scarf and whiskey-breath poet—arrogant and pretentious. Deep inside, however, I was scared, insecure even. Poetry workshops were torture machines, survived by a good deal of smugness to kill the pain. I spent most days reading poetry in Spanish and English, but was easily wounded; a perceived rejection, however slight, put me in a terribly black mood.

Frank MacShane, the director of the program, had translated several novels by the Chilean mystical writer Miguel Serrano. Despite his professorial airs and his faux British accent (he was originally from Pittsburgh), Frank was unpretentious and generous and—in grad school for a vocation like writing—having mentors pay attention to you was first of all a psychological boost, but also could help determine whether you got published in book form or not.

Frank introduced me to the work of the Chilean poets Enrique Lihn and Nicanor Parra—and encouraged me to write to them for permission to translate their work. What I read of their work I liked. But I was barely half their age. If I wrote to them, why would they even bother to write back?

So I didn’t. But I began to translate their poems anyway, without permission. The first translation I ever published was Parra’s “The Final Toast,” bought by The Massachusetts Review for fifteen bucks and slapped on the back cover. I had an oficio: I was a translator. Publishing translations, I felt, established my credibility as a writer: if I couldn’t be a successful poet, translation would do. And even my parents were proud.

* * *

After getting my MFA, I received a call from MacShane. He had invited someone called “Gabo” to Columbia. “Would you do me a favor and accompany him around New York for the next three days?”

“Sure. Is this Gabo a friend of yours?”

“David, I’m talking about García Márquez.”

“Gabriel García Márquez?” I knew that Gabo was his nickname, but I was unsure this was who MacShane meant since he had said the name so casually.

“Yes.”

“No-One-Writes-to-the-Colonel-One-Hundred-Years-of-Solitude-Autumn-of the-Patriarch García Márquez?”

“That’s him,” Frank said, flatly. “Will you take him around?”

“Yes. Yes!” I screamed into the phone and hung up.

* * *

I was to meet Gabo at The Plaza and bring him up by cab to Columbia. Back then, The Plaza was arguably Manhattan’s most famous hotel—where F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald and the Beatles had stayed. Solomon Guggenheim had lived there in the fifties. It had lost much of its luster by the seventies, but it still seemed an odd choice for Gabo, much too elegant and pretentious for someone of such modest beginnings.

MacShane had invited someone called “Gabo” to Columbia. “Would you do me a favor and accompany him around New York for the next three days?”

I had read enough interviews of him to know that Aracataca, his birthplace, was a backwoods, hardscrabble village that had been accurately fictionalized as the Macondo of his novels and stories. And then later, when he had married, he barely supported himself and his family through his journalism. I guess I imagined he’d be more at home at the Chelsea or the Washington Square Hotel in the Village.

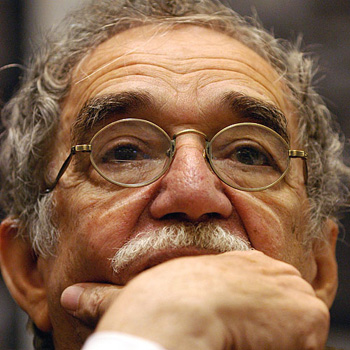

I called his room. He said he’d be right down; I positioned myself to watch all the elevator doors at once. I had never seen him, but imagined he would stand out, maybe not quite like Carlos Fuentes with his Fleet Street suits, but with some kind of distinctive markings. I was disappointed when a short man with a sheepish grin approached, with shiny, speckled black curls on his head. He wore a white sweater with dark slacks, and was in his late forties, about the right age to be my father. Yet he seemed terribly unimpressive, like an appliance salesman or a fisherman on holiday.

We shook hands.

From the look in his eyes, I could tell that in my white shirt and blue blazer, I had also disappointed him. Perhaps I had made too much of an effort to be respectful, but the truth of it was he probably didn’t care who I was or was perhaps distracted by something else. In short, he greeted me with such indifference that I realized he detested being forced to make idle conversation with an awkward 25 year old whom he didn’t care to know. Still, I was determined that I wouldn’t just be his escort, but possibly be his friend.

* * *

We took a cab up to Columbia. It was sunny and brisk; the fall light was sharp and clean. That was when I discovered that Gabo wasn’t much of a conversationalist. He mostly looked out the cab window as we drove through Central Park, wending our way uptown. There was no smile, no warmth in his eyes when I told him that my rent was an honorable $160 per month.

At Columbia, Gabo met with a number of Latin American students, all males, who had taken a workshop with Mario Vargas Llosa the previous semester. The group included two Cuban poets, José Kozer and Rafael Catala; a Peruvian poet and novelist, Isaac Goldemberg; and Orlando Hernández, a Puerto Rican poet and translator. All were at the outset of their writing careers.

He greeted me with such indifference, I realized he detested being forced to make idle conversation with an awkward 25 year old. Still, I was determined that I would possibly be his friend.

In a kind of literary salon, Gabo went around the room asking each student the same questions: where are you from? How did you get here? What do you write? And he would comment upon the responses, almost the way an elderly doctor does when hearing symptoms described. I sat proudly at Gabo’s side. It was clear I had been his escort, but the other writers didn’t accord me any special attention. We were, all of us, timid and awestruck, so much so we could hardly be ourselves.

* * *

The next day MacShane called; Gabo had invited the entire workshop for dinner at Felicia Montealegre’s apartment. A Chilean actress, Felicia was a dear friend of Gabo’s, and Leonard Bernstein’s wife as well. It was my job to call everyone up and tell them to come to The Dakota—the multi-gabled brick and cream-colored brownstone building that had been the site of the Cassevettes film Rosemary’s Baby, Jack Finney’s romantic novel, Time and Again, and the home—since 1973—of Yoko Ono and John Lennon. Most of the student writers were living hand-to-mouth, immigrants who, despite any past pedigree, were invisible in this hostile Anglophone world. Their audible excitement and even squeamishness—how to dress and how to behave?—intensified my own.

When we arrived, we were met by our elegant hostess, clad in a yellow chiffon dress. Bernstein was “out for the evening.” Green silk wallpaper lined the apartment, and an eight-foot cardboard sculpture of a woman, a gift from some Pop painter friend, kept watch at the far end of the foyer. A still life was on the wall: small, but definitely a Matisse.

Then I noticed something disturbing: two tables had been set—Felicia, her twenty-three year old daughter Jamie, Gabo and a few friends (including a woman who wore an arcing ostrich feather in her hat), would be in the dining room. We young writers, however, were assigned a folding table outside the dining room, at one edge of the foyer, close to the apartment door.

We were guests, it seemed, but barely. I was bitterly disappointed and thought to complain. I had been Gabo’s guide and companion; I deserved to be at that table. But more than this, I felt betrayed. I had believed Gabo to be democratic and egalitarian—these were qualities that I saw in his work, and that I held dear. Yet here were all the young writers, sitting by the door. Why had he even bothered to invite us?

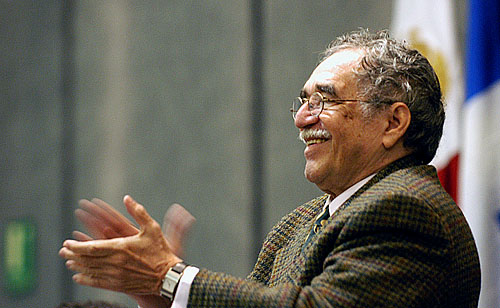

The writer Gabriel García Márquez greets applauding fans during the inauguration of the International Book Fair in Guadalajara, November 29, 2003.

Throughout dinner, I felt strangely segregated. The servants barely looked at us as they fed us chicken marengo, parsley potatoes and buttered green beans almandine, cooked by the house chef. Gabo, our ersatz host, came to the table two or three times and pressed down on one student or other’s shoulders, then went back to his table.

But by then my illusions of friendship and camaraderie were falling away; I didn’t even say goodbye to Gabo at the bookstore or escort him back to the Plaza. I just left.

For our part, we made idle conversation in Spanish; one of us commented on the food. Another replied, Yes, it’s not bad. We would stop in mid-sentence to try and catch some crumbs of wisdom from the main table, anything that might make the dinner worth our while. Like barefoot Indians in the glittering palace of the elite, we heard forks and knives clattering against the china, laughter, quiet conversation—in the other room. An unspoken question flashed from face to face: “So what happens next?”

Soon we had our answer.

At eleven PM sharp, Jamie Bernstein left the dinner party and went upstairs to the cupola of the Dakota where she had a studio. This was our signal to leave.

* * *

The next day, I met Gabo at his hotel. We had grown used to one another quickly, like mismatched shoes occupying the same box; the silence between us had grown familiar. I escorted him to two events: an impromptu get-together for Spanish majors at Hunter College and then later, a wine and cheese party at the Macondo Bookstore on 14th Street, named after the fictitious village in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Before the words were out of my mouth, I felt Gabo’s left arm around me. He jostled me closer to him and squeezed me in the most fraternal embrace I have ever felt.

He talked of the creative process and told an anecdote at both events that he had told earlier at Columbia too, of how he got story ideas from everyday events or dreams. Someday he wanted to write about two brothers who were punished by their parents and locked in their bedroom, he said. The story would pivot on a comment made by an electrician who had repaired a short circuit in Gabo’s Barcelona apartment. “Light is like water,” he had said. “You open a spigot and it flows out, registering on a meter.”

In the story, it would be a boring afternoon until the moment water suddenly began pouring out from a light fixture in the ceiling, flooding the room. The children would climb into a plastic boat and try to paddle out through a window. This was an anecdote, he said, of how a writer can use his imagination to “stretch” reality. But the story, for Gabo, was yet to be written. For now, it existed only as a kind of sketch—story number seven: boys drowned by light—a metaphor for children failing to escape the confining world of adults.

The third time he told the anecdote he glanced at me and his mouth tightened. I smiled as if to tell him that his repetition of it would remain a secret. At least this complicity we had in common. But by then my illusions of friendship and camaraderie were falling away; I didn’t even say goodbye to Gabo at the bookstore or escort him back to the Plaza. I just left. I didn’t see him again either. He went back to Mexico City the next day. And I was sure he wouldn’t even remember me.

* * *

But the following April I received another call from Frank MacShane. This time he wanted me to write a letter to the New York Times, on behalf of Gabo. Frank was too busy working on his Raymond Chandler biography, and since Gabo and I had “hit it off so well,” I would be the ideal author. Gabo wasn’t so sure of his English; he, through MacShane, would feed me the facts. Would I compose the letter? Before I could get puffed up I realized that this was basically a chore; Gabo needed something done and Frank had palmed it off on me. But I was also flattered. He was entrusting his opinions to my words. Though we had never connected when we met in person, here I could acquit myself properly. It didn’t take long before I agreed.

South America in 1976 was under the ferocious grip of rightwing strongmen: Stroessner in Paraguay, Ernesto Geisel in Brazil, Pinochet in Chile, Juan Mariá Bordaberry in Uruguay and Hugo Banzer in Bolivia. With Jorge Videla’s recent military coup in Argentina, there was no safe country for the 10,000 political refugees that had fled there from their homegrown dictatorships. With only four democracies left in Latin America—Colombia, Venezuela, Mexico and Costa Rica—Gabo wanted Argentina to assure these exiles safe passage to one of them. No workshop situation with wannabe poets and novelists, this was a matter of life and death, and I grew proud as I immersed myself in the details of the letter I had been asked to write.

After a series of back and forth calls between Gabo and MacShane, and MacShane and me, the letter was finally written, signed by me in García Márquez’s name, and sent to the New York Times. The paper vetted the letter with Gabo by phone in Mexico City, and it was published on May 10th. Seeing the letter in print was as thrilling to me as the publication of my first translation. MacShane called a few days later to say that Gabo was grateful to me.

* * *

The next time I saw Gabo, 28 years later, I was no longer such a young man. It was during the 2004 Guadalajara International Book Fair, to which Gabo and Carlos Fuentes came to fete their friend the Spanish novelist Juan Goytisolo, who had just won the $100,000 Juan Rulfo Latin American and Caribbean Literature Prize. A rumor spread that Gabo had spent the previous two nights at the Casino Veracruz, a raunchy downtown Guadalajara club where music, dancing, drinking, and groping go on until four in the morning. Both nights, Gabo had allegedly been among the last to leave. This didn’t quite fit with the distant, unassuming man I’d shepherded through New York. He was 77 years old now—the same age my own father had been when Gabo and I had met—and he was in the process of recovering from lymphoma, which he’d been fighting for four years.

That Monday, at a special luncheon for Portuguese Nobel-winner José Saramago, Gabo walked in alone, without his wife, with no entourage. From the cancer, his once tight-skinned face had grown a bit jowly. He moved tentatively in his woolen button-down shirt. The carousing of the night before must have tired him, as had the excitement, no doubt, around the publication of his first novel in ten years, Memorias de mis putas tristes.

I knew he wouldn’t remember me but I walked over to him. He looked at me, confused, as if espying a slightly familiar ghost. When I “supplied a context,” as Allen Ginsberg used to say, by mentioning Frank MacShane, a knowing look crept onto his face.

“I haven’t seen Frank in more than twenty years. How is he?” Gabo asked, his face lighting up and relaxing, more than I had ever seen it do.

“You didn’t hear?”

“Hear what?” Gabo asked.

“He had Alzheimer’s. He died in a nursing home about five years ago.” Before the words were out of my mouth, I felt Gabo’s left arm around me. He jostled me closer to him and squeezed me in the most fraternal embrace I have ever felt.

He wouldn’t let go. “I didn’t know,” he whispered. “Frank was a young man, wasn’t he?”

I’m sure he was seeing the face of the man he had last seen in 1976. MacShane had been born in 1927, the same year as Gabo. I didn’t say anything.

Dozens of people swirled into the room and Gabo and I continued talking for another couple of minutes. He was attentive as I spoke. He actually asked me what I did. I told him about my translations. I even mentioned that that very evening I would be presenting Vivir en el maldito trópico, the translation of my first novel, Life in the Damn Tropics. He smiled when he heard the title and the thought stupidly crossed my mind that because of our old connection, he might show up at my presentation. It’s strange, really. So many years had gone by and I still had the expectation that we had something material in common.

Finally, José Saramago and Carlos Fuentes walked in and someone came to escort Gabo to the table of honor. He shot me one last smile and was gone.

Guatemalan-born David Unger is the author of Life in the Damn Tropics: A Novel, and In My Eyes, You Are Beautiful which is presently being shopped around.