The Shuttering Sickness

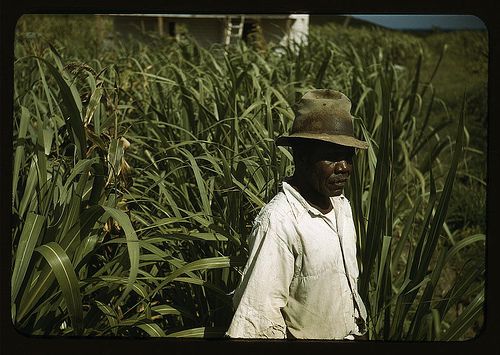

The first accounts of the Shuttering Sickness come from the coastal Carolinas. The earliest known reference to it is in Mary Delilah Briggs’s well-known diary, in which she reports hearing about cases among her father’s slaves from the overseer. It isn’t clear if Briggs ever witnessed a case of the disease herself. She does, however, give an extremely vivid description of its progression, which suggests that perhaps she witnessed its ravages first hand. Today, we are fortunate that advances in medicine and hygiene force us to rely on historical documents for our own understanding of a disease that has been all but wiped out over the course of the last century.

The first symptom of the disease is a feeling of euphoria and calm; a person in the early stages of the illness smiles a lot and laughs uncontrollably at things that aren’t funny. Then he will begin to suffer irritation around the eyes and nose, then swelling. The mouth and ears usually follow shortly afterwards, exhibiting the same symptoms. The hair begins to fall out in clumps. The swelling makes the sufferer’s eyes close up, then his other orifices, the skin knitting over these organs as though healing over a wound, until in the late stages of the disease he resembles nothing so much as a large pumpkin, smooth and oval and sightless. Death comes from asphyxiation as the last puncture of the mouth seals the victim completely inside his own head.

But in those days before refrigeration, ice was valuable and rare; purchased from a merchant each winter, the store of it could not be refreshed until the following year.

There is a story from North Carolina about a man called Solomon who discovered a cure for the Shuttering Sickness. He was a slave. As educated as he’d been permitted to become, he kept the ledger books for his owner, and he had an experimental, scientific turn of mind. He discovered that if you washed the victim’s head in vinegar, it slowed the effects of the illness. If you followed this with the application of ice to the affected areas of the face, the process could be stopped entirely. By these means, he cured several men among the laborers suffering from the condition.

But in those days before refrigeration, ice was valuable and rare; purchased from a merchant each winter, the store of it could not be refreshed until the following year. And Solomon’s cure required a large quantity of this material for each of the sick men that it revived.

The plantation owner set Solomon a task: calculate the relative costs of curing or not curing the sick, the value of the lives he’d save against the value of the ice. Solomon set to work. He took the average amount of cotton that each man could harvest by himself and the average price of cotton over the preceding several years, leaving room in his calculations for fluctuations in the market. He estimated each man’s remaining lifespan—most of the victims were already in late middle age, since the disease struck older people more frequently. He calculated how much work each man had left in him and what profit that work would generate. Then he subtracted the cost of the ice from the value of the work the men would do over the rest of their lives. Against this he set the cost of purchasing new slaves to replace the ones who were left to die from the disease.

No matter how he worked and reworked the calculations, they always came out the same: he found that the ice was worth more than the men. What could he do? He couldn’t bring himself to give the results to the plantation owner, and so each day for almost a week, he’d ask for just a little more time to refine his results. The plantation owner assumed he was finding the calculations difficult and granted him the extra time. Meanwhile, the men in the quarters waited to be saved, as each day their own flesh enfolded them more completely.

In the end, Solomon ran away rather than be complicit in condemning his peers to death. It isn’t known what happened to him or whether he was ever recaptured. But, since they would have made him conspicuous, he left his notebooks with his findings in them behind when he fled, and the plantation owner discovered them and accordingly left the slaves untreated. One by one, they died from the closing of their eyes and noses and mouths.

But there was one thing that Solomon had forgotten to account for in his calculations, which was the possible advent of new cases. The disease, left untreated, turned out to be communicable and spread. First, it spread among the field hands. Then it spread to one of the maids who had a lover among the workers, and then to the mistress of the house and then to the owner, who died later that year. The people who were left alive buried the faceless dead in a field behind the house. The estate was broken up to pay off creditors, and those slaves still living sold to other owners. And in winter when the ice merchant came back to take their order, he found the house deserted.

The Last Video Game

Albert Knaussen-Pritkopf, the man widely credited as the inventor of the video game, was apparently a lonely child. His parents died in a plane crash when he was young, and he had no siblings. He was raised from the age of five by his maternal aunt, who lived alone in a suburb of Phoenix.

A self-absorbed and bitter woman, Pritkopf’s aunt resented her nephew, whom she regarded as a burden and an idiot. The evidence suggests that she was an alcoholic, and she alternated between neglect and abuse. According to Pritkopf’s ex-wife, she used to leave him at home, alone, for days at a time without sufficient food and without supervision of any kind. When she did reappear, she would chide him for any mess he’d made during her absence and chase him around the house brandishing a hairbrush. The beatings she administered were savage.

Pritkopf himself never spoke publicly about this, but in later years he would describe her as “reserved,” or, occasionally, in a moment of particular candidness, “withdrawn.” Nevertheless, his aunt’s neglect was something that dogged him throughout his life. Even as success and fame came to him, he never fully escaped its shadow.

His great interest was in making interfaces that would expand the ways humans and computers could interact with each other. He wanted to make it so that you could, as he put it, “Hold hands with the machine.”

According to the few people who knew him well enough to make conjectures about his private thoughts and feelings, he always felt like an outsider, possessed of an incomplete and patchwork education, a philistine for whom other people were the greatest mysteries of all. But there was one thing that he knew about: screens. He loved their finitude, the way they tidied the world into a single rectangle of space. He loved the hypnotic motions of light across their surfaces.

As a child left by himself, he would watch television for hours, and sometimes he would reach out and try to touch the characters through the glass. At moments of particular trial or celebration, he would try to shake their tiny hands or stroke their hair or pat them on the back. He did this even when he was old enough to know that such contact was impossible, that the characters were just projected cathode rays, because he found it soothing. And from this came his first inkling of what would be his life’s discovery. Over the years, the feeling became an idea and the idea a conviction: the next step would be reciprocity, the TV that could love you back.

At college and then in graduate school, he entered the nascent field of computer science, learning everything he could. He was a gifted student and gained competency rapidly, winning grants and fellowships to support his further research. His great interest was in making interfaces that would expand the ways humans and computers could interact with each other. He wanted to make it so that you could, as he put it, “Hold hands with the machine.”

He began to design simple visual displays, the most famous of which, we all now know, consists of a wall, a paddle that moves laterally up and down one side of the screen at the user’s direction, and a round puck that bounces between them. The object of the game is to keep the puck from escaping from the screen, vanishing and leaving the user bereft. His second interface involved a similar concept of spatial control, except this time the screen was filled with the representations of small, scissor-shaped monsters that descended in erratic paths towards a representation of a gun that the user fired at them to make them explode.

Of course, both of these early designs became widespread and successful, along with Pritkopf’s numerous later designs which include the game with the frog crossing the highway, the game with the giant gorilla, and his most successful game of all: the one in which a small, hungry, yellow sphere tries to eat as much as he can while running away from pulsing and relentless ghosts.

Pritkopf became wealthy from royalties, and this shy man was thrust into the spotlight of national acclaim. He didn’t handle the pressure well. He was infamous for a number of embarrassing public gaffs, such as the time he said that it would be OK to drop the atom bomb on Russia because then some other nation would have a shot at winning the World Chess Championship for a change, or the time when, accepting an award for public service, he mooned a gathering which included at least three foreign heads of state. Pritkopf’s research also suffered; his productivity dropped. Several new designs he’d been working on were shelved because they were judged too complicated and arcane ever to be commercially viable.

In his later years, Pritkopf withdrew from public life. He took to drinking heavily. He had moved back to Arizona by this time. He saw only a few close associates. (It is notable that in none of the accounts of his life does anyone claim to have been his friend). Though none of his later work was produced commercially, he continued to design electronic games.

It is from the people who saw him during this time that the rumor comes of his final unfinished work. No one knows for certain what the content of the game was, but through the years visitors to his home caught glimpses of it: a scribbled bit of code, or a sketch for the layout of the virtual environment. And what these fleeting impressions seem to indicate is that, just before his death, Pritkopf was designing a gafme with the following parameters:

You are a young child left alone in the small, dim rooms of a suburban ranch house outside of Phoenix. You are hungry and there is nothing to eat. You have to climb up onto the counter of the kitchen and search through cupboards in which there is nothing but boxes of macaroni and cheese. You must light the burners on the stove and make this meal for yourself even though you are too short to see what you are doing. In the advanced levels, there might be milk in the fridge; in beginning levels you must make a choice between using water or eating ketchup from the bottle with a spoon. If you spill anything from the pan, a tall, gaunt figure arrives and she pursues you through the rooms of the house, shouting at you angrily about how she never wanted to raise you and how ungrateful you are. In spite of these and other obstacles, you must successfully get your macaroni and cheese to the living room and turn on the television and eat it all without spilling anything on the carpet; if you do this, you have won.

Surgery: A Love Story

For a while, in Hollywood, it was fashionable for actresses to have sections of their nervous systems removed. The idea behind the surgery was this: because the nervous system is what makes us react to the world, wrinkle and crease our faces, flinch, frown and grin, its removal would retard the aging process, if not prevent its physical effects altogether. Unfortunately, there were side effects and unforeseen consequences. Without their nerves, these women burned and cut themselves without realizing they were doing it. They fell and didn’t feel it. One woman walked around her house on a broken leg for three days without noticing she was injured; after this incident, the surgery was outlawed, but it was too late for those who’d undergone it already. They would live with the consequences for life, which included numbness in the affected areas, lack of coordination, and loss of reflex response.

In Malibu, there lived a beautiful old woman without a nervous system. She’d been an actress when she was young, and she’d starred in a few films and had some small parts on TV. Her agent had encouraged her to get the “neuron readjustment therapy,” as it was then called, and she’d thought that it would give her more time to become a star. In fact, after the surgery, her face on film looked oddly immobile, as though someone was configuring its expressions by remote control, and as a result her career dwindled and fizzled out. She was offered fewer and fewer roles, then none at all.

She led a quiet life: she ate a diet of jellyfish with the stings removed: they were spongy and tasted like glue. She drank sea water with lemon juice. She swam in her pool. She worried about the sun exploding one day in the future and about whether talking on the telephone spread diseases.

Still, she remembered the parts she had played fondly. In her most famous role, she’d played a beautiful woman who watched and gasped and sighed while the hero of the film first saved a small boy from drowning and then saved the boy’s entire village from evil priests with shaved heads and strange tattoos. The film was set on a Pacific island. In the end of that film, the hero kissed the woman on a beach then went away to war while the woman and the boy whom the hero had saved from drowning waved to him from the end of a pier. From the sad music that played, the woman knew that the hero was never coming back.

That was years ago. Now she lived in an undulating house of white, uncertain rooms with a long lawn below it that ended in a cliff above the ocean. Mostly she didn’t miss her nervous system, though she had to be careful and have her maid check her for injuries every few days in case she’d hurt herself. She led a quiet life: she ate a diet of jellyfish with the stings removed: they were spongy and tasted like glue. She drank sea water with lemon juice. She swam in her pool. She worried about the sun exploding one day in the future and about whether talking on the telephone spread diseases.

Things continued this way for years, until one day a man broke into her house by climbing over the high wall that surrounded it. The woman herself found him when she was watering her garden. He was crouching in the bushes near her swimming pool, watching her with big, scared eyes. He seemed familiar to her, though she couldn’t think where she had seen him before. He stood up, and she thought about whether to scream or not as he stepped out of the shrubbery and came toward her. For some reason, she didn’t scream or run away. She just watched him approach.

He stopped when he was standing only a few feet away from her. He said:

“I won’t hurt you if you give me that necklace you are wearing.” The woman put her hand up to her throat and touched the pendant that hung there. It had been a present from the man who’d played the hero in the movie she’d been in, and she didn’t want to give it up. She said to the man:

“I can give you something else more valuable but not this.” She looked at his clothing to see if he might be armed, but he didn’t seem like he was carrying a gun.

He said: “No, I want that necklace,” and he lunged for it. The woman turned her garden hose on him and sprayed water in his face, which stopped him for just long enough so that she could run away. She started running up the hill towards her house, but she couldn’t go very fast because she had to be careful not to damage her numb feet and legs. She glanced back over her shoulder to see if the man was coming after her, and she saw that he was, but not very quickly. He was also running in the slow, ungainly way of a person who could not feel his own feet. She was so surprised by this (she had never seen a man with her condition) that she forgot to be afraid. She turned around and watched the man struggle up the slope. He seemed even more familiar to her than before.

She said: “Who are you? Where do I know you from? If you tell me, I’ll give you the necklace.”

The man stopped running. He said: “I was the boy in the film, whose village your lover saved. I got this surgery because my agent told me it would make me more handsome. Now I can’t do anything; I can’t even work a regular job because I’m too clumsy.

“I have loved you since I was a child. Even then, I wanted you to stop ignoring me, and I wanted to touch your beautiful round stomach and run my fingers over the heft of your thighs.”

The woman looked at the man. She unclasped the necklace from around her throat and held it out toward him. He waved it away. He didn’t even want it anymore.

“I just wanted to see you again,” he said. “I’m sorry if I scared you.” He started to walk away up the hill. He looked defeated, walking with his head down, watching his feet to make sure he didn’t twist an ankle.

“Wait,” she said. “Please.” He stopped. She came up the slope to where he was standing. “Did you have the whole thing removed?” she asked him.

“No,” he said. “Did you?”

“Well, I was meant to but the surgery was not fully successful. So there are a few places where I can still feel things.”

“Where?” he asked.

She reached out and touched his head, then his knee, then his chest. The ocean below went on crashing, flinging gulls into the air.

“I’ll show you,” she said.

Fat Man’s Last Meal

When they were ready to detonate the bomb, the scientists all withdrew to a safe distance and put on their protective goggles. From the safety of their shelter, they looked back at the site of detonation through binoculars.

Now, looking back at the scaffold, the director of operations gasped audibly and put a hand up to his mouth.

The bomb itself was round as an apple and hung from a pyramidal scaffold made of wood and placed up on a small hillock that rose out of the desert plateau. Someone, one of the junior technicians with an unruly sense of humor, had painted a big, smiling face on its side in white paint. Another had given it a pair of papier-mâché ears. Another had glued a fake beard and moustache to its metal casing. Another had given it arms made of rubber tubing, which ended in white lady’s gloves, a walking stick, and a pair of boots. When they left it hanging on the scaffold, one of them had patted it genially and said how much they’d miss it, which in a way was true.

Now, looking back at the scaffold, the director of operations gasped audibly and put a hand up to his mouth. It was nearing dawn, blue light filling the air, and soon the desert sun would come sheering over the blue hills at the edge of the plateau, and so he could see, quite clearly, that the scaffold they had left behind was empty. He swallowed, afraid for the first time since they’d begun work on the project, all the fear he’d held at bay rushing in on his heart from all directions at once, crushing it. Hardly able to speak, he signaled for a couple of guards to go back to the scaffold and find out what had happened.

Where was the bomb?

The guards drove as quickly as they could over the dry, uneven desert ground. Nothing grew in that place but creosote bushes, which crouched like green spiders close to the earth. When they reached the scaffold they jumped out of their Humvee with their guns at the ready, their hearts flapping like wings. They hadn’t wanted this job. They knew what it might mean. They looked up at the scaffold, and sure enough it was empty. They heard a noise, a shuffling, snuffling, grunting sound, something disturbing the loose stones of the dry desert ground. They went around the base of the scaffold in the direction of the noise, and there it was. They watched it, aghast, unsure of what to do next. It was rooting around in the scrub grass at the base of the wooden beams with its walking stick, searching for beetles and grubs and snakes. When it found one it waddled forward on the old, beat-up army boots that served as its legs, then bent down with great difficulty, since its shape did not lend itself to easy flexibility, and snatched up its wriggling prize, a giant centipede, in its glove. It held the centipede up to examine it. Then it popped it into its mouth. They heard the crunch of smashed exoskeleton. They thought they heard a sigh of contentment, too.

Suddenly, it looked around and saw them standing there watching it. It put down the scarab it was about to consume and started to run away. They were amazed how fast it could go considering it didn’t really have any legs. They followed after it, and after a couple of minutes they realized a terrible fact: it was running in the direction of the scientists’ shelter. The guards looked at each other, and in a moment, without speaking, they made a decision. They turned around and ran the opposite direction. They ran to their jeep and jumped inside. They drove as fast as they could over the stony, uneven ground. When the one of them who wasn’t driving glanced behind him, he saw the stout shape still heading away from them, towards the ridge behind which the scientists were sheltering. It wasn’t very steady; sooner or later it would trip over a rock or a pothole and then, well… The guard thought of the men and women in the shelter, and he felt sorry for them, but he didn’t stop. He kept going, and then, suddenly, inevitably, came the flash, the shock wave that sent him sprawling sideways onto the ground, the roar of the atmosphere sucked upward into a spire of flame. He got to his feet again and kept running, the fire racing along behind him, faster, faster, coming up behind him, igniting the air itself…

Did he survive? How else would we know this story? Years later, when he was a old man, sick for years from that day, he would learn that the center of the blast radius was just at the top of the ridge behind which the watchers crouched. And he thought: they must have seen it coming. They must have watched it tottering towards them up the slope, using its cane for balance, wobbling over the rocks and stones, grinning all the while.