This story is an edited chapter from the author’s forthcoming novel What Kept You?, to be published in Australia and New Zealand in July 2025.

I was eight, and when I saw the sack that was Uncle Saith’s body lying in the dark of his porch, I felt the hard slab of the marble on which it lay leak cold into my spine. In the years that followed, you gave me a hundred reasons to doubt what my body stubbornly remembered. You countered my claim by insisting I never really did see the body, that it was discovered so late at night, flung carelessly within the boundary walls of the Saith’s house, that I was in bed fast asleep for hours by then. You pointed to the boundary wall, topped by a thick layer of smashed glass, that separated our house from the Saith’s; you insisted that borders, especially those topped by glittering glass shards, were enough to prevent crimes of one place from spilling into another. You told me that the news only reached me in the morning, that the news never was meant for my ears, and I only snatched shreds of it flying between you and Mama while I spooned cornflakes doused in sugar and hot milk into my mouth.

I remember the taste of a mouthful of mushy cornflakes but I also remember the sudden bloom of red staining a white marble floor under a crumpled body that looked like a sack.

Uncle Saith’s murder wasn’t the only crime committed in the house next door on that date. The crime before the crime, the first crime, had already happened and, if not in waking, then at the mouth of a dream, I witnessed a mangled body at the same time when Poonam Aunty flicked on the 100-watt light bulb of her porch, saw her husband’s body, and uttered her first shriek. The shriek raced through the dark, knocked open doors, and crashed through windows, rousing you and I and Jahangir all the way down to the only single-story house in the entire lane, right at the edge of the neighbourhood, where the Madboy lived – remember that boy who got drunk on bhang every few nights and threw the word randi at the moon, mistaking it for the face of his lost love – the shriek knocked at the Madboy, he looked up at the moon; it made a round turn and flew right back to Aunty Poonam, standing on her porch, her husband’s body at her feet, crashing into her and knocking her to the ground.

But before the shriek, before the body and the stain, and the flicking on of the bare bulb, before Poonam Aunty fainted and collapsed in a bundle next to her husband’s dead body, before she recovered her senses and started shrieking again, there was a celebration at Saith’s house, the only Hindu house in the whole country – and I was invited.

Of course we had been inside the house before, but you had always accompanied us, and our access to the house was limited to its salon. Everyone knew the salon was furnished under Poonam Aunty’s watchful eye to greet Muslim guests who came calling. A Muslim salon, bereft of any idols, towering or diminutive, or posters of Kali posing with a dagger in one of her eight arms, a severed human head in another, a foot set on her husband’s chest, lying at her feet, her red-hot tongue sticking out, her ravenous mouth a cavern.

The Hindu House was adjacent to ours, separated by a common wall. But it wasn’t an ordinary house made of bricks and cement and slabs of faultless white marble and leafy gardens at its front and back but one whose walls and windows and driveway and trees professed to us a religion other than our own. There were idols in that house; we knew, everyone knew.

One evening, a neighboring grandmother whispered to you, sitting on our front lawn amongst five other grandmothers perched on steel chairs while I stood nearby, pretending to pick jasmine heads from a flower bed. “I hear black magic is done in that house. Once, I was walking down the road, you know, after my knee surgery, I had started gaining weight around my stomach. I felt like a cow, I couldn’t even breathe properly. Baji, this weight had become such a big problem.”

“You mean it has become such a big problem.” You tilted your head a little and shot a smile my way.

Another neighbour, eager to get to a grisly story, urged her on, “We know about the weight. We can see it. Tell us what happened with – that, that, house.” She flicked her head toward the wall that separated our home from the Hindu House.

“Oh, I was walking. Trying to get at least fifteen minutes each day. And I was walking past, and I saw the head of a creature, maybe a goat, maybe a dog, lying at their gate. Blood oozed everywhere, and the eyes, Baji, the eyes still open. I hear they sacrifice animals for the statues inside. Blood is involved.”

“Why, you had to walk at night? You couldn’t do it in the day?” This came from you, steering the subject back towards the speaker.

Another one piped in. “They say they look like devils. The things inside. That’s why no one has ever seen the inside inside of the house. They make guests sit in the salon. Baji, we don’t even keep prints of living things in our house.”

The woman sitting closest to you spoke up. “No, no Baji. They have a special room in there. My husband, may Allah have mercy on his soul, my husband went to the house to speak to Saith about hiring a guard for the whole neighbourhood. Too much trouble in the city. Of course, the salon is for normal people but you know my husband– important man – he was led right inside. He said he saw a room full of statues, even bigger than him – half demons, half animals. When he returned home, he had a fever. He passed away soon after that. I blame the Hindu House for it, I tell you all.”

“You all are new here but I’ve been visiting that house for thirty years now and I’ve never seen anything there. They never bothered showing anything to us. Why they thought you people worthy of this show and not us people?” You raised your voice, and spoke. The women knew better not to pursue the topic.

No one knows this, but when Jahangir was given the binoculars you brought back from Hajj, there were no parrots with red-ringed necks in that jamun tree whose branches drooped over the boundary wall and retched purple berries on the driveway of the house next door. Under the pretext of bird-gazing, Jahangir and I transformed into neighbourhood sentinels. The sole TV channel available to us played its favorite reruns; war, war, and, more war; the last three showdowns between India and Pakistan reassembled from grainy footage, reanimated in perpetual déjà vu. We sensed war in the air. Hiding out in the balcony’s far left corner, where the bougainvillea spilled its pink guts, we staged our own siege. The gardeners, the milkmen, even the mailmen dragging their burlap sacks became soldiers, their hands cradling imaginary Kalashnikovs. Crows wheeled overhead – no longer crows but fighter jets, their wings carved sharp as folded knives, their beaks primed to drop bombs. We ducked behind the railing, hands clasped to our ears to soften the shriek of their shadows, and waited for the world to end one afternoon at a time.

On days when our imaginations ran dry, Jahangir and I snuck into your room while you napped, the fan chopping the air in lazy circles. We pilfered the daily newspaper, its pages still crisp with the smell of fresh ink, and peeled it open to the middle section. There, between government announcements and black magic ads, the cinema listings unfurled like a gallery of nightmares. The Pashto horror films screamed in black and white: heroines with black blood oozing from their necks, their bare midriffs, their thunderous thighs slick with dark gore, splayed helplessly in the arms of coyote-faced demons. Hiding out under the canopy of creepers, we gazed at the newspapers, horrified and hungry, imagining the demons closest to us.

Jahangir never did spot any idols, and most summer afternoons I stretched out on my back on the brick floor of the balcony, heat pressing its weight into my limbs. Above me, the canopy of creepers quivered in the slow spin of the breeze, their green tang staining the sunlight. They climbed out of the balcony railing, their tendrils threading into the curlicue grills on the upstairs windows. On days when the torpor relented enough to let my fingers twitch, I turned those pink flowers, the ones that loomed above our heads like a hundred uncalled for chandeliers, into necklaces and bracelets. By the time Poonam Aunty made a phone call to you and invited Jahangir and I to her youngest daughter’s birthday party the next day – four sharp, a fashionable time for all birthday parties to begin back then – I had a whole jewelry collection at my feet.

When you relayed the news, Jahangir and I looked at each other, and I saw his eyes light up.

But before I could decipher if it was apprehension or anticipation that we both felt, your crowish eyes pinned us in place. “Don’t embarrass me there,” you said, your words of warning dressed as advice. “Behave like children from a shareef home. Don’t touch things that don’t belong to you. And don’t fight with each other.” Jahangir kicked the edge of the rug with the tip of his chappal, but I nodded solemnly, though my hands itched to shove him, just once, for the sake of it.

So, off we went, bearing an Estee Lauder lipstick set and a box of chocolates wrapped in shiny silver cellophane. On that day of crimes, I wore a frilly sea-green frock, its ruffles bouncing with every step, drawing my own eyes to their flair and sway. I had never stepped on the road by myself, although a pack of boys did play cricket there in the evenings. Jahangir and I often watched them from the front gate, pressed against its wrought iron bars. In less than a year, Jahangir would leave me behind the gate to join the other boys. But at four pm that day Jahangir and I stayed side by side, on the grassy strip of land that edged the thick hedges guarding each house in our lane.

Jahangir went first, his voice steady with borrowed righteousness. “If there is an idol in there, we’ll return home immediately.” I didn’t answer. I looked down at the road. So many cars and so many feet had already trod on the asphalt that it was chiselled smooth, silver specks glinting in the afternoon sun. I had an urge to bend down and lay a finger on the road, pick up a fleck of glimmer on my fingertip. ‘Look, even if there is something there, we’ll just eat the cake quickly and come back. They’ll have black forest cake, I’m sure.’ Jahangir considered this for a moment. ‘Okay, but we won’t even look their way. We’ll just look somewhere else. You know if we do, Qari Saab said we could burn in hell.’ Jahangir used this moment to shift the parcel of gifts from my hands to his own.

I looked down at the road again, empty at this hour, right to the fork that ended our lane and branched out into unknown routes. I didn’t know then what roads did to children, how they opened their mouths and swallowed children whole. I could’ve followed the silver dust, speckled here and there, whichever route it would’ve led me to, but on that day, I placed my hands on one corner of the silver wrapping paper instead, and hurried on besides him.

The older girls gathered in the Hindu House’s drawing room wore georgette shalwar qameez. They had silk ribbons braided in their hair; that was the rage amongst high school girls back then. I touched my fluffy bob as soon as I walked in. The cool of the air-conditioned room lapped against me. I quickly surveyed the room: high walls, spotless glass windows with a view of a gnarled tree trunk and its drooping branches, the jagged outline of the boundary wall, and, there, a tendril of the creeper from our garden snaking up. “Jahangir, look, our balcony…,” I spun around to show him but my brother had abandoned me. He had scurried off to join Suneeta’s younger brother on a sofa, his shoulders angled away from me.

Left to myself, I hovered at the edge of the room until I found the safest spot – one corner of a cream-coloured recliner that seemed too large and too soft for me to sit on properly. I perched on its edge, my legs dangling awkwardly, my hands balled into my lap.

No one spoke to me, the youngest girl in the room. A bubble began to rise in my throat, tight and bitter, as I eyed Suneeta’s brother, sitting in my place next to Jahangir. Suneeta’s brother was nearly Jahangir’s age, two years older than me, but he never stopped by to play cricket with Jahangir nor called out to us from the other side of our wall.

My birthday that year had been the grandest of my life. Not only was a fruit cake bought from the bakery, but two of Jahangir’s friends had also been invited. They gorged on the cake after belting out a Punjabi version of the birthday song that replaced the word happy with haathi, effectively announcing to the room that it was a birthday party held in honour of an elephant. I didn’t know how I felt about the only two guests mangling my birthday song and blowing out my candles for me. It was only when we were ushered to the dining room of the Hindu House that I realized what a flop my birthday had been. The long oak table stretched before us like something out of a magazine. Platters gleamed under the overhead lights, heaped with homemade sandwiches. Carrots carved into flowers bloomed alongside meat pies nestled in glass casseroles. Pink muffins with swirls of cloudlike icing sat in neat rows, and at the very center of it all, on an elevated cake stand, was a Black Forest Cake.

Fourteen candles shimmered at the periphery of the cherry-festooned cake. Poonam Aunty bustled around with a clunky camera, arranging the guests around the birthday girl for pictures. Suneeta’s friends and family started singing happy birthday, the English version, in unison. Suneeta was dressed in a pink and white chiffon shalwar qameez that matched the icing on the muffins; she gathered her long hair over one shoulder and bent delicately to blow out the candles. The room erupted in applause; everyone clapped – but not me. I didn’t want to look at the birthday girl or her cake or the smoke rising above the candles like snakes.

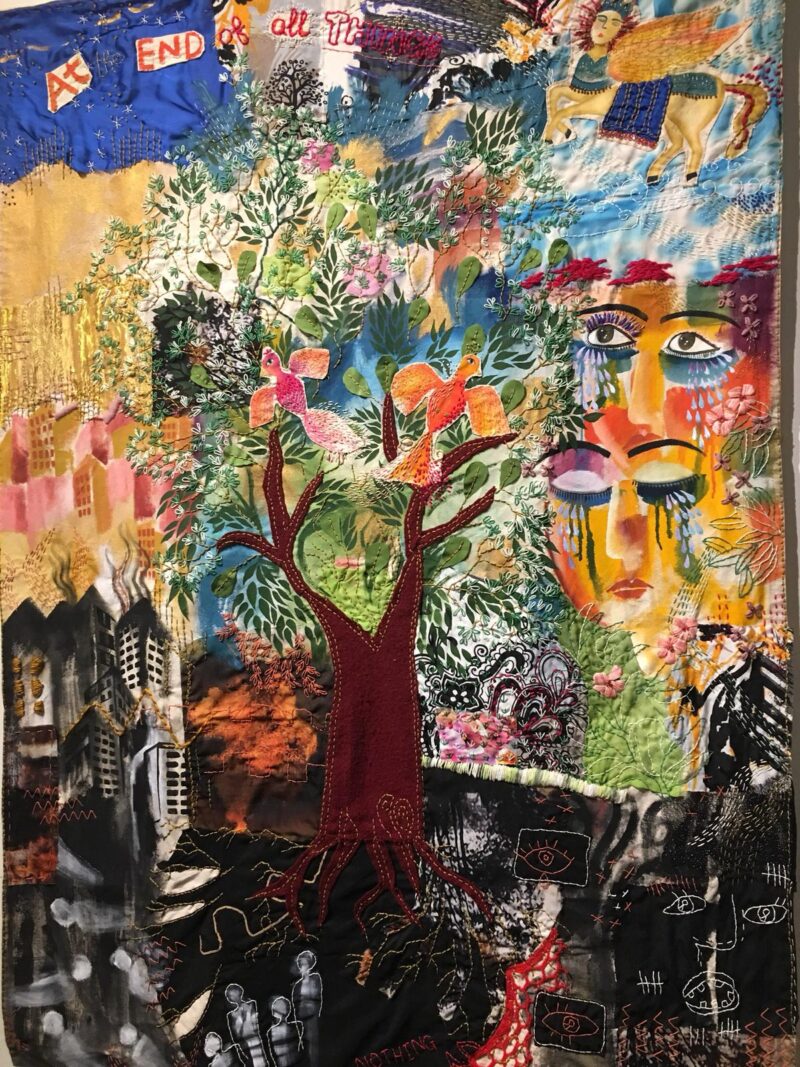

I edged away from the crowd. There was a dark corridor at one end of the dining room; I crept down to its threshold. Doors lined the narrow corridor on both sides, which ended at a wall. Set into the rear wall was a niche lit by an earthen lamp.

From where I stood, I could make out small shapes within the niche – figurines, arranged in a perfect circle around the lamp. I took a hesitant step forward, and then another, the details sharpening with every movement.

There was a chubby elephant with human arms and hands, a palm raised above its potbelly, trunk swept to a side, a tiara perched between the ears; there was a figure – its gender indistinct – crowned by a top knot, one leg bent at the knee and the other lifted as if mid-dance; a blue-skinned figure clad in a white sarong, a golden flute raised to its lips.

The steady flame flickered, cast shadows and light across the wax faces. I stopped when I could see them whole, poised in the orb. They seemed alive, caught in mid-action, their stories paused within the glow.

I know my throat went dry, I know I pursed my lips, my pulse hammered in my head, and I bunched my hands into tight little fists. I know I shouldn’t have, I remembered my pact with Jahangir, but the sudden sight of the forbidden demanded infidelity.

I extended a hand and seized the figurine.

In my palm, the figurine felt solid and supple at the same time. The face that gazed back at me was smaller than the nail on the smallest finger of my hand. I glanced behind me; no one had come looking for me. I turned around and brought the figurine close to my eyes. That face lacked nothing; there was the forehead, set high and smooth, there was the nose, raised gently at the bridge, cheeks faintly flushed tangerine against honey-toned skin. Hand-drawn eyes stared wide ahead. There were the lips, pursed just a little. The neighbor’s god seemed amused by me.

I clamped my fist around it and jammed it down in my pocket. It left a sheer film of oil on my fingertips.

It wasn’t until I had eaten my share of cake, received a pink goody bag—with an unblown balloon, a pencil, and a strawberry-shaped eraser—and was walking back on the grassy strip of land along the houses that it struck me: I had stolen from the neighbours. I was carrying the evidence of it right there in my dress.

Jahangir turned to me. “So, Nani’s old hags of friends were wrong,” he said, his voice verging on triumph. “No idols in there.” I fingered the wax figure in my pocket, feeling the weight of my crime. “I saw an idol,” I said.

Jahangir froze mid-step. His hooded eyes dilated, his fingers, still chubby then, landing on my shoulder. “No! What did it look like?” I looked down at my frock, at the pocket at its side. I thought about turning away, walking to the nearest hedge, and tossing the figurine into its tangled arms. But Jahangir was watching me, a dent forming between his brow. The dent scared me. Lying to Jahangir was lying to the mirror; there were laws between us that neither one had broken yet.

Years later, Jahangir and I will spiral into a fight over Suneeta’s brother calling persistently at the house for me. Jahangir will hurl the telephone set in the wall, its wire releasing it with a crash before I finish calling him bhenchod, the most blasphemous street curse ever to escape from the mouth of a girl within the four walls of a shareef home. By the time I realize what my filthy mouth has uttered, and in what incestuous way it has implicated both him and me, Jahangir will have marched out of the house, grabbing the keys to the car that he will not be old enough to drive just then. He will drive the car to the cycling velodrome, that steep concrete bowl a foolish construct in a city where only a despised handful could afford to ride bicycles for sport, and steer his car down its slope. A stink will rise like a gurgling storm, the tires will screech as they catch the incline, their rubber burning against the concrete. He will step down on the accelerator, going faster and faster and faster still, watched by the boys on the rim perched on the bonnets of their cars, waiting, in silence, for their respective turns to prove themselves men. For a stagnant moment, Jahangir will wonder if he will fly, at last, at last, before the car swerves and spins out of control. Jahangir’s car will flip once in the air before succumbing to the laws of this world. A group of boys will arrive at our house to offer their condolences before the news of the accident will have reached us. You will spin around and look at me, livid with blame and rage, ready to combust. “What have you done?”

The telephone set, wireless and splintered, will lie silent at my feet. Jahangir will return home, somehow barely scratched, with stories to tell of what happened in the cycling velodrome, but it will be the first episode, in a string of episodes, that will make strangers of us.

The sun was about to set, but the day’s heat hung heavy between us in front of the Hindu House.“You don’t remember what Qari Saab said about people who keep idols?” I was already sweating under all the ruffles, but at the allusion to hellfire, something smoldering bloomed inside me. I fought back the tears. “Maybe they weren’t idols, Jahangir. They just looked like really pretty dolls.” Jahangir thought about this for a moment. “Let’s go back. I want to see them. You know, to make sure.” I couldn’t hold back the tears. I took out the figurine from my pocket and held it up in my hand. You were at the gate by then, calling out our names. I jammed the figurine back in my pocket while Jahangir stood horrified by what he had witnessed. There was no time for either one of us to rescue the other.

At night before bed, Jahangir asked you about the fate of thieves. You were one of those people whose kindness life had aimed to beat out of you; your kindness had persisted, against all odds, but it had curdled in your mouth. You were the one to name me Jahan, the world, and my brother Jahangir, the protector of the world. You, our grandmother, authored the roles in our origin stories. With their heavy filigree of crow’s claws, your eyes scrutinised our faces, from mine to Jahangir’s and back again, searching, gauging, all the while. Your gaze settled on Jahangir’s face. “Perhaps it happened, or perhaps it did not, but they say many, many days ago in India a thief was caught in an open bazaar.” All of your stories were set in India. India to us was an insatiable monster, always en route, always jumping over a wall on its bloated feet, lurching towards us; India to you spelled the home you could never return to, the one you left behind at the time of the Indian subcontinent’s butchering. “What was his crime? Hunger. He stood by a loaded cart and gazed too long at the piles of bread, the stale ones from the night before hidden beneath layers of the ones freshly baked just that morning. They say his legs swayed. You see, he was famished. The boy fell on top of the cart. The cart toppled on top of the boy. When the cart owner dragged the boy from underneath the rubble of bread, the boy’s mouth was working hard, chewing on a piece of stale bread.” You paused here and emphasised that this thief was only a child, so scrawny that his ribs pushed out against the cage of his skin. “The bazaar gathered their hands on the child and dragged him to the court of the Badshah by his feet. The punishment for theft was what? Cut off the stealing hand. But by the time the thief reached the court, he had bitten his right hand so many times that it had started to bleed. The Badshah took one look at the thief, saw the bleeding hand, the protrusion of his ribs against his skin, heard about the loaf of bread that had, by then, become a rumour, and gave orders to set him free. The thief became a child again and sat with the ruler that day for a royal feast.” Here you paused, raised your voice, and wagged your finger at our faces. “But the self-inflicted wound in his hand festered, and he never again could eat with his stealing hand.”

By the time we prepared for bed my body betrayed me, heat radiating off my skin. I gulped down the spoonful of red medicine, the kind that smelled like cherries but tasted like kerosene and climbed into bed, refusing to take a bath or change out of my dress.

All night long the heft of my sin pushed against my thigh, my body sweated under the sea-green ruffles, and when I heard the shriek from Saith Uncle’s porch, growing dim and loud as it surged through the street, I knew something red and fierce had been unleashed.

In the morning Jahangir woke with a plan. “Don’t worry, Jahan.” He whispered from across the room. “We just won’t tell anyone. Give me the idol, and I’ll throw it down from the balcony into the Hindu House.”

I put my hand in my pocket to retrieve the figurine. But there was no figurine left; all through the night the heat from my body had worked on the wax and coalesced the doll into a jumble of colours stuck to the inside of my pocket. I tried to scrape it off; some of the pieces remained unyielding, stubbornly clinging to the rest of what once made them whole. Some bits loosened and came away in my fingers in a mess of mangled limbs.

Later that day, our street swarmed with battered police cars, their sirens shrieking pointlessly. The neighborhood aunties stood on their balconies, fingers pressed to their teeth. The neighborhood uncles marched in and out of the Hindu House, looking busy in their smart clothes.

Down the street, a cluster of strangers gathered around a man carrying a camera slung over his shoulder and another holding a microphone to his face. They moved as one, a shifting pack, pausing every few steps to murmur and point at the house, their voices low but insistent.

Flower vendors across the city caught whiff of a rich man’s death and pedalled to our street, their cycles piled high with the choicest desi roses – fuchsia blooms plucked fresh, petals soft and fragrant. They came ready to barter grief for profit, but many turned back, their baskets still brimming with wares, without offering to sell them upon learning of the religion of the inhabitants of the Hindu House.

I remained despondent – fearful of the fire that awaited me, mourning the beauty I had so briefly possessed, guilty at the horror my sin seemed to have unleashed. The late afternoon heat pressed its fist down on me, heavy and relentless. I lay on my back in my hiding spot, the air thick and still. Then, out of the stillness, a flower caught my eye.

In the dappled sunlight, the flower shone translucent with only a faint blush of pink. A newborn bloom, smaller than the nail on my smallest finger, six simple petals fanned around a pale green core.

I lifted myself and crouched on my knees. I pinched at the stem, sniffed at the petals; there was a thrill of sugary scent, but so faint that the more I sniffed at it the more it slipped away from me. I ran the flower on the side of my face, closed my eyes to the soft slide of it.

I shot a glance at Jahangir. He sat still as a hound on scent, binoculars pressed to his eyes. I looked down at the clutch of flowers that I had gathered earlier, wilted at my feet.

I plucked the new bloom off its stem, opened my mouth wide, and placed it on my tongue. I chewed slowly – through the petals, the centre, the wispy stem. I ate it.

Is there a better way to make something yours than to devour it whole?