Gottfried Kirchbach, Frauen! Gleiche Rechte—Gleiche Pflichten. Wahlt Sozialdemokratisch! (Women! Same Rights—Same Responsibilities. Vote Social Democratic!), 1919. Lithograph printed in red and black on wove paper mounted in linen. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of the Robert Gore Rifkind Foundation, Beverly Hills, CA (M.2003.114.34). Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

In the fall of 1918, as soldiers returned home from war and the Western world turned inward to begin its slow recovery, a new fight broke out in Germany. In late October, as Germany’s defeat appeared imminent, disillusioned sailors in the German Imperial Army mutinied, setting off a series of worker strikes across the nation. The country fell into turmoil, and by November, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated power and fled, leaving a flimsy German Republic in his wake. The Bolshevik spirit that was sweeping through Russia infiltrated Germany, and Communist factions and radical left-wing parties sprung up, demanding change. Outraged veterans and disenfranchised workers and citizens protested in the streets, and political parties formed and splintered. A violent struggle ensued, leading Germany into a civil war to determine who would shape what would ultimately become the Weimar Republic. From November 1918 to August 1919, Germany was an embattled state.

The exhibition AKTION!: Art and Revolution in Germany, 1918-19, now on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) through January 10, takes as its focus this often-overlooked period. Bringing together image-driven propaganda posters, intricately composed lithographs, influential political magazines, and rare books, AKTION investigates a volatile moment in Germany’s history, shedding light on the deeply held belief at the time that art had the power to effect political change.

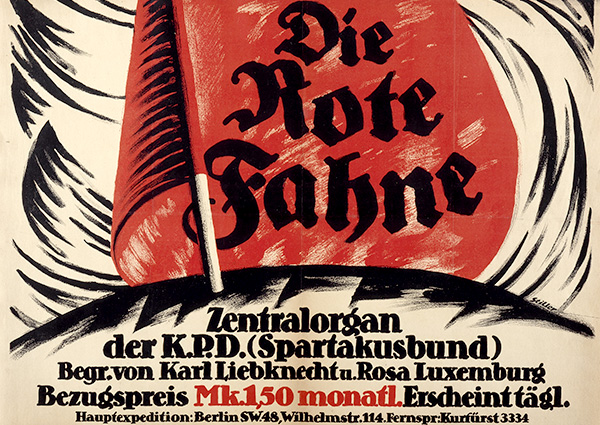

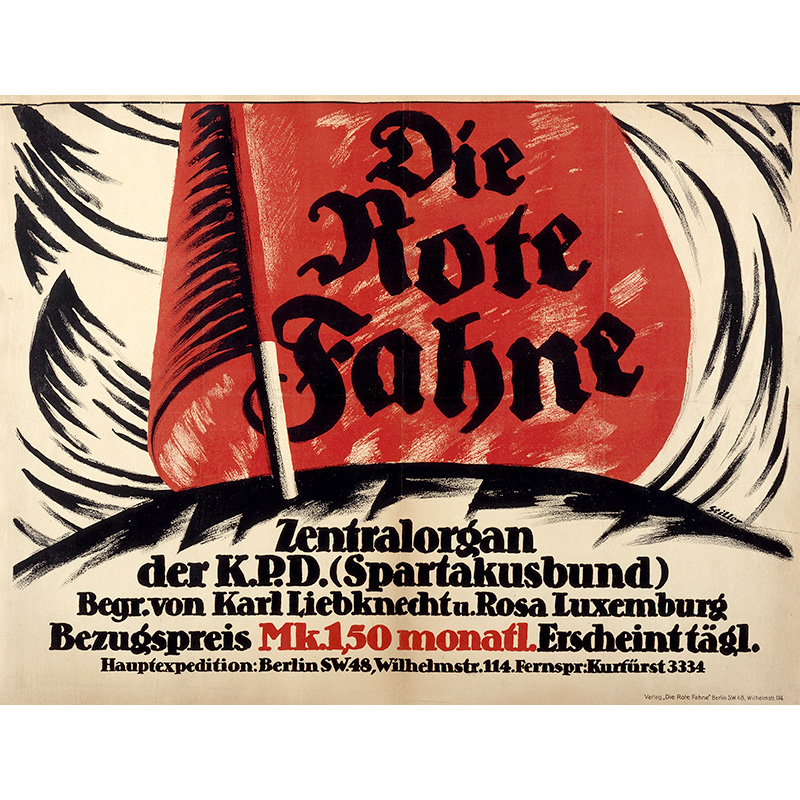

1918 to 1919 was a time of tremendous upheaval and progress—women were granted the right to vote and the eight-hour workday was mandated for laborers—but it was also a time of turbulence. The government assassinated two high-profile Communist leaders, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, and workers led two uprisings that ultimately failed. The works on view—from lithographs created as public art and propaganda to woodcuts printed onto poster-size paper—highlight the desperation and heightened drama of the moment with images composed of harsh, angular lines and printed in bold shades of red, black, and orange.

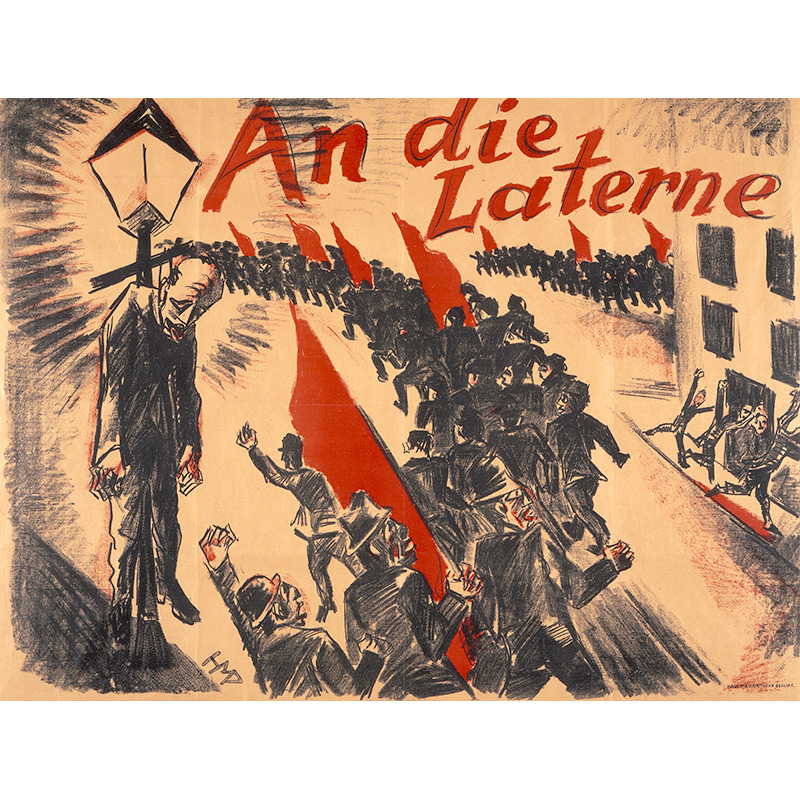

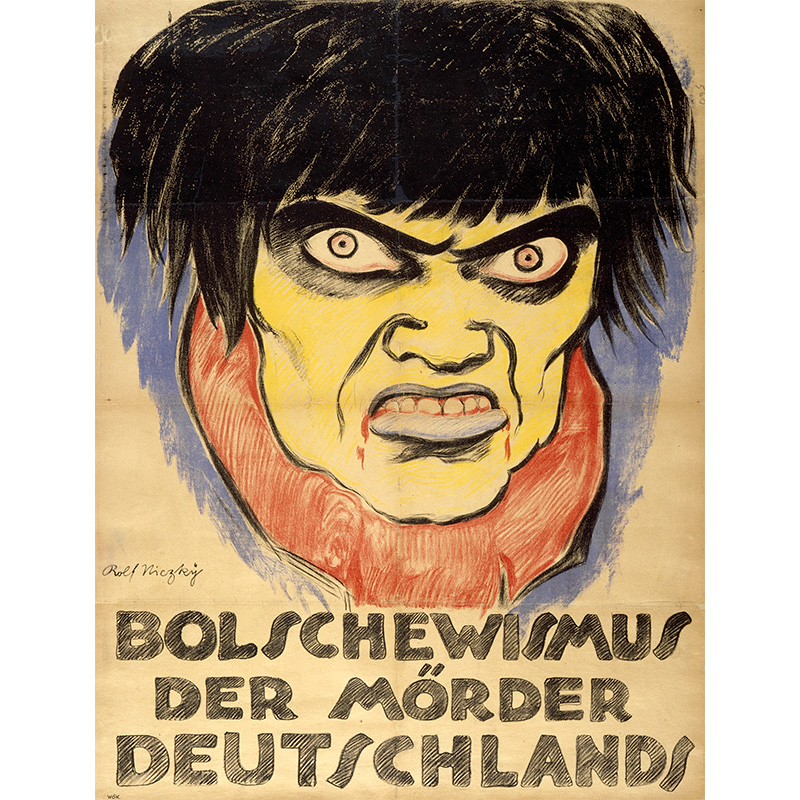

Composed in the Expressionist style that was dominant, many of the works depict figures comprised of elongated bodies, angular faces, and distorted limbs leaping from the page, beseeching people to heed their message, protesting against Bolshevism, urging for order and democratic process, or imploring mothers to vote. The government ran a well-oiled propaganda machine, churning out posters through the Publicity Office and posting them in the street, and the competing political parties—from the Communist-run Spartacists to the Social Democrats—followed suit. While well-known artists were being published in magazines, others worked independently, creating their own pieces in reaction to the chaos that surrounded them. Text was present, though sparse. The posters on the street and the accompanying media revealed a battle waged largely in images.

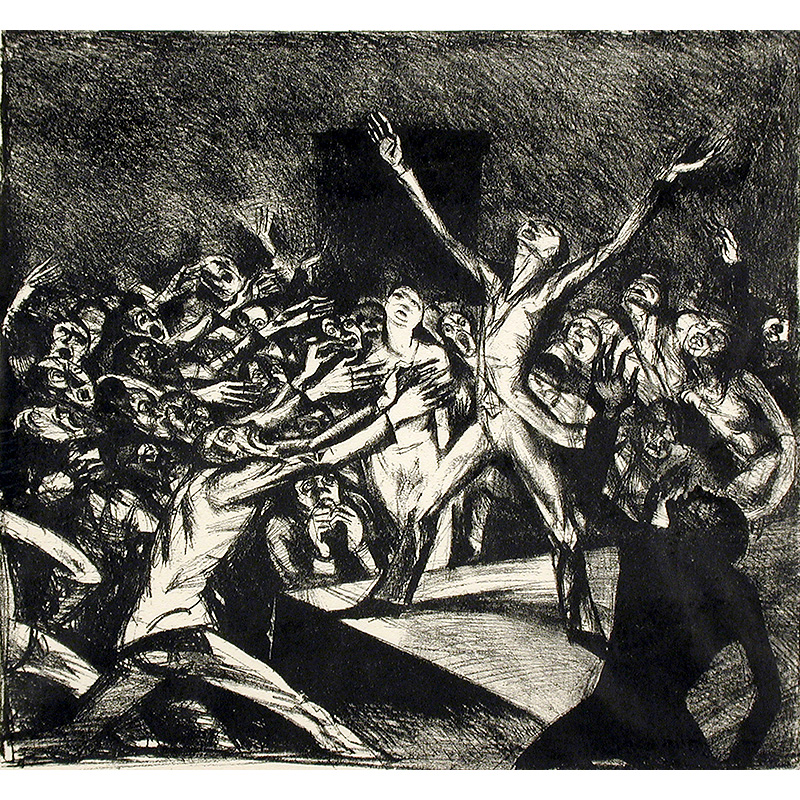

Among the most striking works on view is a series of lithographs by the artist and political cartoonist Erich Godal. With ominous titles like “Dance of death,” “Chaos,” and the quietly desperate “Bread!” the haunting lithographs convey the bleak desperation of the moment. Depicting anguished, gaping crowds—hungrily reaching upwards in “Bread!” or with arms raised, shouting at the ostensible government leaders rallying from a platform above, in “Chaos”—the works teem with life. Forged from circular, swirling lines, they contain an innate velocity that, even decades later, draws the viewer’s eye up, where it demands more, asking what’s next. Wordlessly, Godal was able to craft conflict, desire, and hope through near-mythic imagery that continues to resonate today.

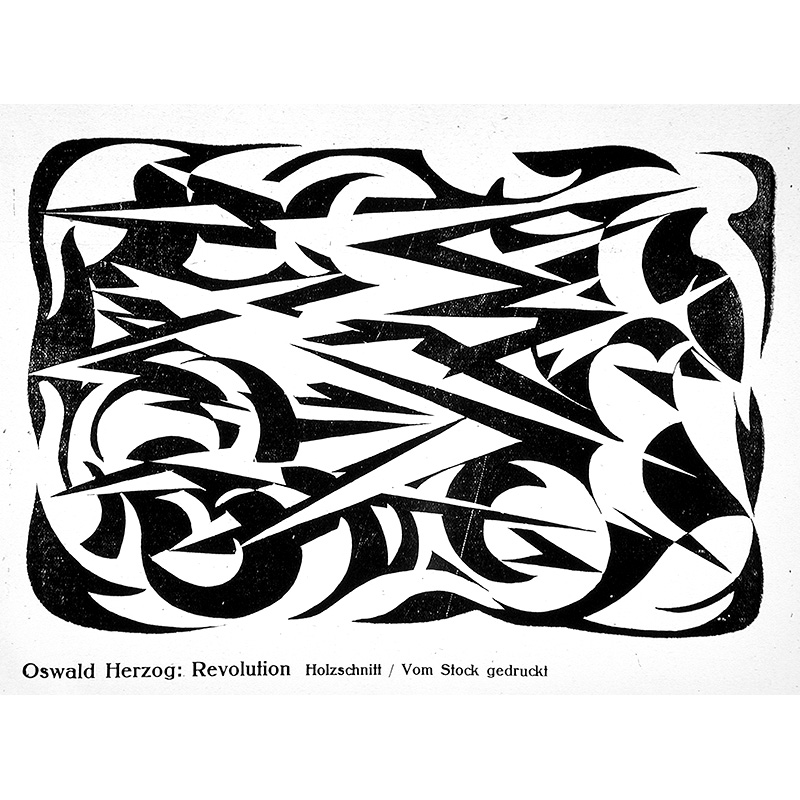

Original copies of the magazines Die Aktion and Das Plakat, as well as prints of woodcuts and lithographs that appeared in each of the publications, are also on view. Die Aktion was founded in 1911 by Franz Pfemfert as a literary and arts magazine, but began to focus more heavily on politics after the start of World War I. Even in 1919, though, when it took on the highly political subtitle “Weekly Periodical for Revolutionary Socialism,” it remained committed to original artwork as an influential tool. Works like Herbert Anger’s “Die Revolution (The Revolution),” an abstracted woodcut whose shattered lines depict angry citizens protesting in the streets, and the anonymous “Capitalism,” which features a distended face hording skulls, graced the cover of the publication, providing the framework for the political tracts contained within.

Similarly, the graphic-design magazine Das Plakat turned an eye to politics. Keenly aware of the powerful art that was being created, Das Plakat began publishing and archiving propaganda posters at the very same moment as they were being produced. The publication went so far as to dedicate a special issue to the political poster and featured a seminal essay by the prominent art critic Adolf Behne, which argued for the political poster’s ability to move people to action.

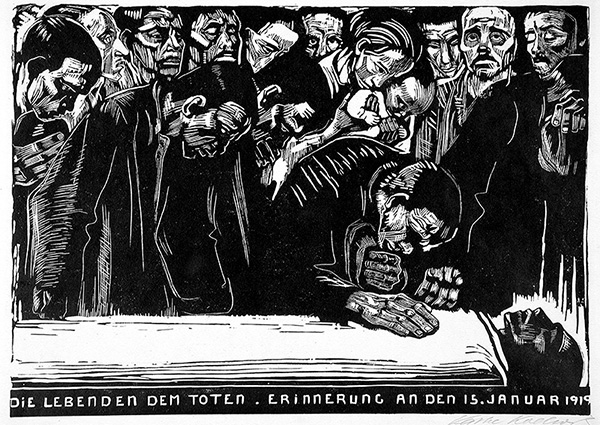

Throughout the exhibition, artfully crafted propaganda posters, like Max Pechstein’s “Don’t strangle the newborn freedom through disorder and fratricide, otherwise your children will starve to death,” depicting a stout, naked infant gripping a red flag, and propaganda-like art, such as Käthe Kollwitz’s “Memorial sheet for Karl Liebknecht,” featuring a grieving crowd surrounding the coffin of the assassinated leader, are put into dialogue, offering a glimpse of what Germany’s city streets might have looked like at the time. Taken together, the works reveal the firmly held hope that even in the face of violence and struggle, progress was possible, and that art could be a catalyst for achieving it.

One of the most notable aspects of the exhibition, though, is also perhaps the most inadvertent. In a quick and undiscerning glimpse around the room, one immediately takes in the glaring black and red imagery, the angular lines reminiscent of Brutalist architecture, and the stark text accompanied by vibrant, and oftentimes violent, illustrations. The immediate association with the Nazi propaganda that cropped up just over a decade later is nearly unavoidable. The artistic style and political tactics that we now associate with Hitler’s regime are here present in a far more measured form—shilling for the working class, protesting the assassination of Communist leaders, urging women to vote, and transporting us to a critical movement that helped Germany’s recovery from the upheaval of war.

Abby Margulies is a freelancer writer living in the Bay Area and the senior arts editor for Guernica.