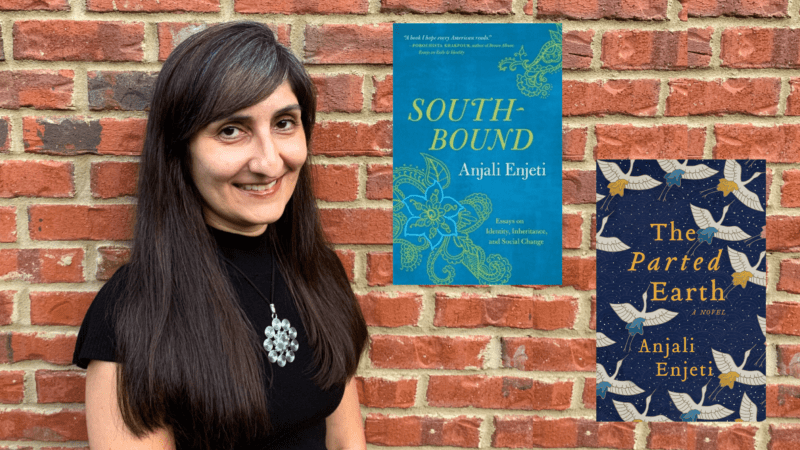

Anjali Enjeti published not one but two books this spring: a novel, The Parted Earth, and an essay collection, Southbound. Both are remarkable debuts, focusing on lives that do not receive enough careful attention in US literary culture. The novel traces four South Asian women across time and geography from mid-twentieth century Asia — when, in 1947, their lives are forever changed by the partition of India and Pakistan into separate nation-states — to Trump’s America. It’s the story of women exploring their histories and coming into their own later in life, despite great odds. Southbound charts Enjeti’s political awakening while growing up in Detroit and after moving to Chattanooga in 1984, when she was ten, as well as her experiences contending with discrimination and coming to terms with her identity as a woman of Indian, Austrian, and Puerto Rican descent. In a nod to the collection’s title, Enjeti writes of representing “multiple souths” — South Asia, southern India, and the American Deep South. In both works, she’s sensitive to such complexities in herself and her characters, and the ways they animate a life.

Enjeti’s persistence in the publishing world drew us together a few years ago. We’re both South Asian women writers who launched our creative careers after navigating the complexities of jobs and family, and the sheer challenge of breaking into publishing in midlife and as women of color. Enjeti is a former-lawyer-turned-activist, an award-winning journalist, a creative writing teacher, and the mother of three children. A reported essay she wrote for Guernica won the South Asian Journalism Award. She also co-founded the Georgia chapter of They See Blue, an organization that mobilizes South Asian voters to engage in progressive US politics.

Now that Enjeti has two books out, I wanted to catch up with her and see whether she believes things are changing in the publishing industry. Over email and on the phone, we talked about foregrounding older women narrators, the importance of connecting with our ancestral histories, and why the publishing world still needs to evolve. I came away with a sense of why identity is at the heart of all her work. As she told me, “When people don’t see you for who you are, and what your possibilities are, it has real political consequences.”

— Jenny Bhatt for Guernica

Guernica: Your activism and journalism focus on underrepresented and oppressed groups. Now that you have two books out, how do you see the relationship between your activism and your creative writing?

Anjali Enjeti: I find storytelling and activism to be one and the same, in the sense that activism gives people a platform so they can share their stories in an attempt to build sociopolitical power. Organizers like myself are essentially scribes. We help community members understand the issues, how they’re being affected, and what the potential solutions are in order to help shape the narrative and write an ending that is satisfying.

With They See Blue Georgia, for example, we’re helping eligible South Asian voters understand that the story of America, of governance in the United States, and of who has power in the US, is predicated on their ability to exercise their right to vote. We tell them they have a chance to change the narrative of this government by writing a different story for our country. We try to get them to see their individual voices as part of the larger narrative of our future as a people.

Guernica: In Southbound, you write about how you came into activism. When did you first begin to think about issues of identity and politics?

Enjeti: Vincent Chin’s death in 1982 was a first for me in many respects. I was eight years old and living in a suburb of Detroit. Our house was about 15 miles away from where he was killed. Two white men who were laid-off auto workers murdered Chin out of frustration with Japanese people and the Japanese auto industry for taking jobs away — as they saw it — from the US auto industry. Chin was Chinese American. There was a civil suit, but the two men never paid a single dime. They never spent a single day in jail. They got to go on and live their lives.

When I heard this story, playing on a loop every evening in my house, it was the first time I thought seriously about the idea of what’s fair. That was also the first time I really began to understand Asian identity (though the term “Asian” wasn’t used that much in the early 1980s; it was “Chinese” or “Japanese” or “Vietnamese” or “Indian” or “Paki” — largely, racial slurs.) On TV, we saw Asian folks taking to the streets, marching, and speaking out. I saw Lily Chin talking about her son, crying and being angry. That experience of figuring out that justice isn’t always served, and that often people get away with horrific acts of brutality, was shocking. I began asking questions about identity and power: What is race? What is racism? When does the legal system work and for whom? What can protest do?

Forty years later, I’m still trying to answer many of these questions.

Guernica: In the essay “The Unbearable Whiteness of Southern Literature” in Southbound, you write about how, in the wake of Vincent Chin’s murder, you didn’t have the right language or imagination to work through those [questions]. It wasn’t until much later that you began to find it. Can you say more about that?

Enjeti: In college and beyond, I came across work that I wish I’d encountered a decade earlier, including Maxine Hong Kingston’s The Woman Warrior — the first book I’d read from a brown woman who was unapologetic about her opinions, about the world, her childhood. She just made a space for herself. Also, in Sister Outsider Audre Lorde was completely unapologetic about her identity as a Black lesbian, her interracial relationship, and expounding on and pushing for the kinds of equality we’re still grappling for today. James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time was forthright and fearless, like: Here I am, I’m not going to meet you halfway, you have to come to my space and listen to me. Baldwin knew he was smart; he told people they had it wrong and needed to change. That was revolutionary for me to see. In the small Southern city where I grew up, you didn’t talk to people like that. In the Deep South in the 1980s, likability was everything. To see Baldwin being confrontational, which I’d always been told was rude and made you look conceited, was inspiring.

These were all writers making their own rules for how they wanted to live their lives and move in this world. They were not here to serve anybody, but to create a world that saw their value. There are so many others I wish I’d discovered earlier. Instead, in middle school and high school — crucial times in one’s cognitive development — I read white-authored classics that didn’t push me in my personal and emotional growth. They didn’t teach me to think critically about the world in a way I needed to. From seventh through twelfth grades, I read four of Shakespeare’s plays. What a difference it would have made to substitute these other books for three of those plays.

Guernica: In that same essay, you write how books like To Kill a Mockingbird and The Help fetishize Black pain to redeem white characters, and how reading them enables white readers to create white savior narratives instead of looking at their internalized racism and complicity. You also write about being a guest on The Oprah Winfrey Show at age twenty-five. After filling out a form on the show’s website, in which you explained that you’d found fault with Oprah’s book club pick, Mother of Pearl by Melinda Haynes, who was a white woman writing from the perspective of a Black man, you were invited on the show as a critical voice. How did that experience shape your identity and politics?

Enjeti: Being a guest on that show in the 1990s was, in the words of Oprah herself, an “aha” moment for me. Until that taping, I had suspicions about books — who was allowed to tell certain kinds of stories — but I didn’t know how to begin the conversation. At the time, these issues weren’t even addressed in the field of criticism. Twenty-five to thirty years ago, there were very few staff BIPOC critics, and editors at newspapers and magazines weren’t exactly rolling out the red carpet for BIPOC critics to call out white authors for writing problematic books about non-white characters. This movement, which I credit to critics like Roxane Gay and groups like #WeNeedDiverseBooks, is a relatively recent phenomenon.

What being on Oprah did, though, was inspire me to become a different kind of reader: one who not only thought about how a book fit into the larger cultural and literary conversation, but about the publishing industry’s role as literary gatekeepers who control what stories get told by whom, and what stories never see the light of day.

Guernica: Yes, it’s frustrating that, despite the evolving conversation about diversity and cultural sensitivity, we still had American Dirt, which Oprah picked for her book club last year. It remained on the NYT bestseller list for months. Why do you suppose that we, as a society, keep repeating this?

Enjeti: This is an interesting question, and one I struggle to answer. First of all, there are too few people in positions of power in publishing who possess the critical lens to look at stories as possible vectors for harm. I don’t think we have enough editors who, when sitting down to read a manuscript for the first time, ask themselves what basic assumptions the author is making to tell a story about a particular community, and whether these assumptions are harmful.

And part of the reason this remains an issue is because we seem to hold the belief that writers have some inherent “right” to tell whatever story they want to tell. I don’t know if it’s because I came to writing later in life or because I’m a BIPOC writer, but I’ve never felt entitled to tell any story that comes to me. I must have dozens of drafts of essays and novels and short stories that I quit working on because I realized I did not have the necessary lens to write a particular piece.

Guernica: You’ve said that the India-Pakistan Partition, which is a significant event in your novel, isn’t a part of your personal family history. What compelled you to write an entire novel about it? And how do you see yourself avoiding the pitfalls of cultural appropriation made by the authors of American Dirt and Mother of Pearl?

Enjeti: I was scared to death, and so I hired two professional authenticity editors because I wanted to get it right. They each gave me feedback on The Parted Earth and also my essay collection. Despite spending years doing my own research, I also hired a Partition historian for The Parted Earth to make sure there were no glaring inaccuracies or inconsistencies in the story. I think if writers, agents, and editors could approach the process of publishing more humbly, and more sensitively, perhaps we’d have fewer American Dirts.

I started researching the Partition fifteen years before I knew I wanted to write a book about it. There were so few stories of survivors preserved. That haunted me. The first archive, the first formal widespread effort to collect stories, was not created until 2007 — six decades after 1947. This isn’t true when it comes to other major events in history, like World War II. It didn’t take sixty years before somebody decided to create a Holocaust archive or museum. In the 1990s and early 2000s, an organization called the Citizens Archive of Pakistan was one of the first to do this work, and the one I finally came across in about 2014 was the 1947 Partition Archive.

The central question for me was: What happens when we don’t know our family history? This is also the central question for Shan, the novel’s protagonist. Does it affect our lives, especially if we have no idea that an ancestor was connected to something so horrific? And when there are fifteen million refugees, and one to two million people who died, millions of stories were lost. And even if you don’t know about it, it can completely shape your life.

Guernica: In The Parted Earth, I loved your focus on older women, ranging in age from forty to eighty. As you know, I also spotlight older women in my fiction. Can you say more about your choice to focus on older women’s agency?

Enjeti: Women are the keepers of our heirlooms and the guardians of our ancestral stories. Their experiences, memories, and wisdom go a long way to guiding the rest of us in how to navigate our joy, grief, and trauma. Our elders have also had more time to process the events of their own lives, and this perspective is invaluable to the generations that follow. So when the idea of the book came to me in late 2011, I knew the elders would ultimately be the key to unlocking the story. It’s also one of the reasons a crane is featured in the book. Cranes, like the elders, symbolize longevity and endurance.

I feel so connected to my ancestors’ energy and spirits, and I take comfort in knowing that they have persisted through some of the same challenges I have. The older I get, the more deeply I feel their presence in my life. When COVID-19 first hit, I was in a sort of shock. For the first several weeks, the fear was beyond overwhelming. I never thought I’d see the day where I’d be terrified to go to a grocery store or have to talk to my husband about updating our will because of a global pandemic. What calmed me was thinking about how our ancestors have faced plagues and pandemics and wars. They survived, and because they did, we can too.

Guernica: I’m thinking of this line from the novel: “There was something about the age of forty, that sort of midway point of life, when people started to feel the need to be connected to the generations before them.” What does that mean to you?

Enjeti: My Indian family members are originally from Chennai and ended up in Hyderabad, so they were not directly affected by the Partition. But the quote is an honest reflection of something I felt very deeply when I turned forty. Suddenly I had an urgent need to connect to my ancestors’ stories. By that time, three of my four grandparents had long passed, and Gertrude, my only living grandparent, had Alzheimer’s. So I no longer had direct access to their stories.

Shan’s disconnection from her heritage and her history is analogous to a different part of my family tree. My Puerto Rican maternal grandfather died very young, when I was six years old, and at the time of his death he’d been estranged from his family for decades, due in part to a terrible tragedy that happened when he was a child. Because of this, I have no connection to my Puerto Rican culture. I don’t know a single Puerto Rican relative. And like Shan, I find myself, in my forties, compelled to find these long-lost relatives and link back to this part of my history. I think it’s important for all of us to be amateur archivists of our family histories. I feel like we’re more secure in the world, more balanced, more confident in our identities, if we know this history of ourselves.

Guernica: In your essay collection, you discuss your long path to publication and the struggle you faced in getting editors to invest in your work. “For years I pitched a novel about an Indian immigrant family who ran a gas station in a small North Georgia town….A few years later, a white Southern author published a novel that featured white characters and wove in elements of Hindu mythology,” you write. “Here I was, an Indian Southerner trying to sell a Southern story about Indian Southerners at a time when no other Indian Southern author was publishing novels about the South. And a white Southern author beat me to it.” Now, with two books published in quick succession, do you believe the publishing industry is more open to writers of color?

Enjeti: I’m feeling faint optimism at the number of Black people who have been appointed to senior positions at major presses lately. And I’m excited about groups like Dignidad Literaria and their push for structural changes. But to be honest, I feel as if BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, disabled, and other groups are still doing the bulk of the work to end white supremacy in publishing. In the literary world, do marginalized editors, publishers, agents, and authors ever get even five minutes where they don’t have to think about bigotry in the industry? I doubt it.

Equality in any field is oftentimes found in failure. I’d love to read an absolutely terrible big press book by a Black or brown author with a huge advance, who then gets another contract at a big press after selling virtually no copies of their first book. Or I’d like to read about a brown or Black editor who royally screws up but is forgiven and gets to keep their job. Once marginalized people in the industry regularly start receiving better opportunities after doing poorly, just as their white colleagues have, then we’ll be getting somewhere.