Anuk Arudpragasam’s debut novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage, takes place over a single day near the end of the Sri Lankan civil war. The novel’s protagonist, Dinesh, has been pushed, with fellow beleaguered citizens, to the coast. When we meet him, he is living in a camp, helping tend to the wounded and bury the dead, his existence overwhelmed by the needs of those around him. Civil war raged in Sri Lanka from 1983 to 2009, but the novel doesn’t detail the history of the war. Instead, it is driven by Dinesh’s internal life, like this moment during a wave of shelling:

While keeping us anchored in Dinesh’s body and immediate experience, Arudpragasam is able to talk more broadly about the nature of life in a war zone. Bombing wouldn’t usually be thought of as a calming experience, but for Dinesh it brings mental silence, a break from the constant work of existence within a foundering country. While this isn’t a true story, it reflects behaviors observed near the end of the war. It became common for families to marry their children quickly—especially their daughters—in hopes of saving them from the violence, sexual and otherwise, of the army. Such a marriage gives the book its title, and imparts on Dinesh a renewed sense of his future amid the ever-pressing present.

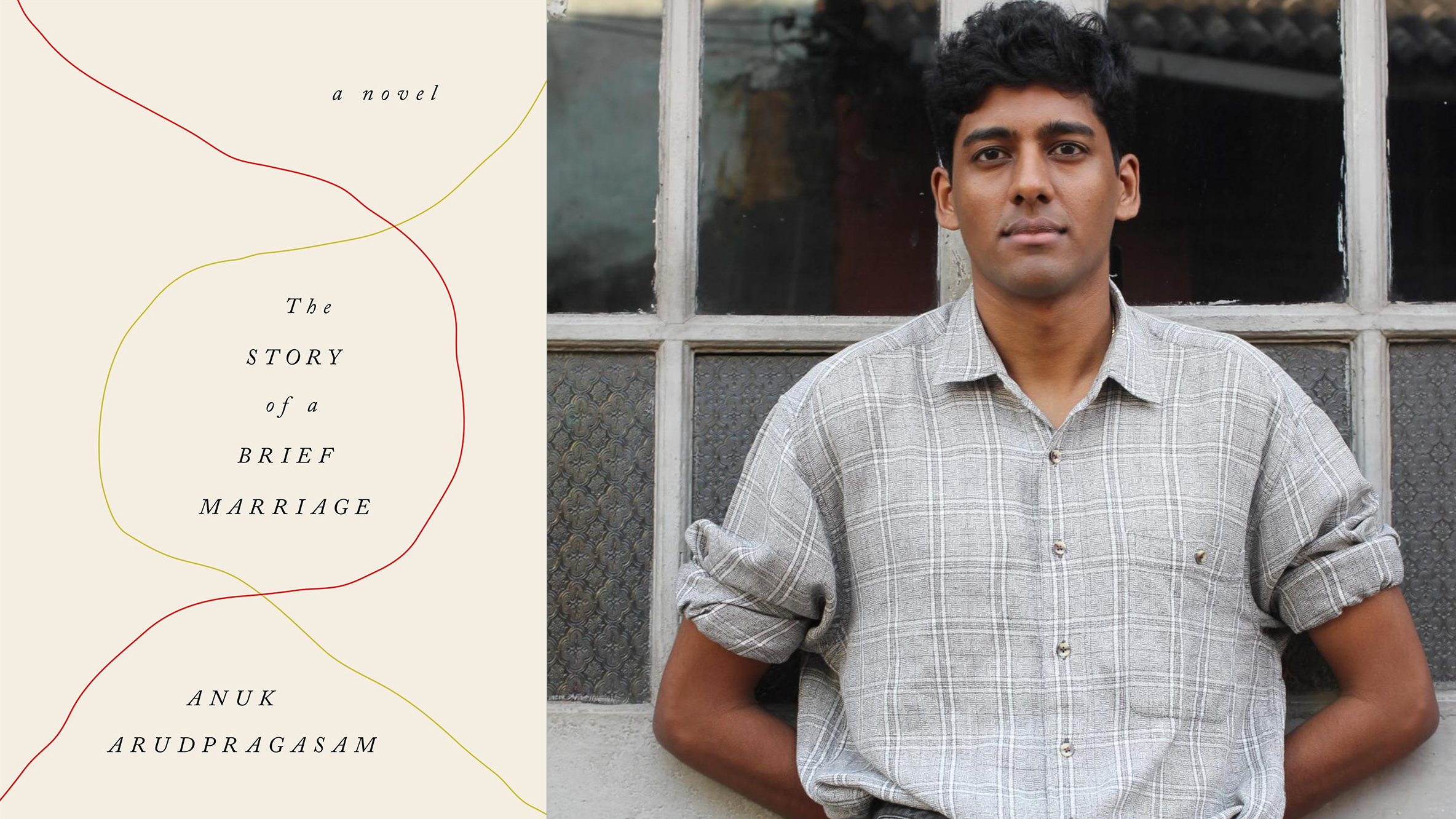

Arudpragasam grew up in southern Sri Lanka, insulated from the war by his family’s affluence. The novel, he admits, “was written out of guilt.” He writes in English—the language of his education—and has been well received in the English-speaking world. In the New York Times, Ru Freeman wrote: “This is a book that makes one kneel before the elegance of the human spirit and the yearning that is at the essence of every life.” A PhD student in philosophy at Columbia University, Arudpragasam has shifted away from the interests that led him to the program, but remains there since it is funded and allows him time to write. And though he doesn’t intend to go into academia, philosophical thought suffuses his fiction.

When we spoke over the phone, Arudpragasam was affable and polite yet unsparing in his critique of the literary establishment and the relationship between colonialism and the English language. He’s a writer attuned to, and unafraid of, discomfort—an essential quality in our current moment.

—Sarah Hoenicke for Guernica

Guernica: How did you approach writing this book?

Anuk Arudpragasam: Everything that happens in it is pretty accurate to actual events, but the story and characters are completely made up. I didn’t think much, to be honest, about the story. I don’t care for stories, for creating characters and writing about events, so I tried to think about that as little as possible. When I was writing, if I had to think about it, I would, but it was in the form of a concession rather than something I did out of actual interest.

Guernica: That’s an interesting thing to hear from a writer. What do you care about when writing?

Anuk Arudpragasam: I care about articulating states or conditions that we don’t have easy language for. I care to find ways to articulate aspects of the inner life. I’m interested in writing as a form of introspection. You have psychology of the mind, psychology of the body, to articulate the inner life. I must decide about events that happen outside a person’s body, because we have language to describe things that happen in the outside world. You can only get to the inner through the outer. So, I do have to talk about things that happen, but what I want is within the bounds of the body.

Guernica: When did you begin working on The Story of a Brief Marriage?

Anuk Arudpragasam: I started it in July or August of 2011 and finished in October of 2014. It’s about things that happened in my country to people in my community that I did not myself experience. I grew up in the south of Sri Lanka in a well-off family, as insulated as someone could be from the war. It was an attempt to cross certain kinds of differences in experience between myself and these many other people in the north of the country who I had become separated from. It was very much an attempt to understand a certain condition very far from my own. It was written out of guilt kind of. Not guilt really. Yeah, guilt.

Guernica: Have people been upset that you didn’t directly experience the war, but still wrote about it?

Anuk Arudpragasam: I have not met anybody who feels this way. The responses I’ve heard have been positive, and I’m sure there will be negative responses, but I simply haven’t come across them yet. Part of the writing of the novel was that the author is writing from a position of distance. Towards the end of the novel, there is a passage in which the narrator wonders what Dinesh feels, and says, “Well, it’s impossible to know, really.” On the one hand, it has to do with the trauma Dinesh has gone through that makes him inaccessible, but it also has to do with the fact that the narrator is writing in a different language, and the narrator has not gone through such an event himself. I tried to make that explicit. This novel is not the novel of a person in such a condition. It’s a novel of somebody attempting, from a distance, to understand the condition of a person in such a situation.

Guernica: Could you talk about your writing process?

Anuk Arudpragasam: I don’t want to talk about my actual process of writing because it’s something personal. The thing I can say is—because of the subject matter, and because it involved me engaging with a mood and materials that were very, very dark—that writing the book involved a disjuncture. It involved a sharp disjunction between my writing life and my non-writing life.

For several hours every day, I would be in this world, in this mindset. After, I would leave the house to go to campus to teach a class or to meet my adviser. I would go out in the evening to meet a friend. The mood required by these interactions outside my room, outside my writing life, was very different from the mood required during the hours in which I wrote. It involved a very strong sense of two highly juxtaposing worlds within me when I was writing. Moving constantly in and out of these worlds—my inner life, my outer life—caused a lot of strain. It was difficult for me not to be aggressive or resentful towards people around me, or, in general, the world around me. Also, I was mainly living in America while I wrote, where people don’t know or talk about Sri Lanka, even though Americans are part of the same imperialist order that played a big hand in the conflict in Sri Lanka and what’s going on in conflicts all over the world. It created this strain of participating in these two worlds. At a certain point, I realized that I needed to finish dwelling on this material sooner rather than later, so I hurried the second part of the novel. I gave myself three or four months to finish the last four or five chapters.

Guernica: After finishing, did you experience a change in yourself?

Anuk Arudpragasam: A huge change. Just not having to deal with this material, not having to look at all these photographs of broken bodies, at these pictures of people who aren’t quite looking you in the eye. It was just not pleasant, and I was glad to be done with it. I’m not trying to say that it was any kind of experience, or that I went through anything that deserves pity. I’m just saying that I was glad that it was over.

Guernica: Your writing is very straightforward and easy to understand, while also putting forth big ideas about what it is to be a person. Do you think that will carry over into your next project?

Anuk Arudpragasam: Yes. My next book—I’ve written about a third of it—will be similar. The situation and conditions are going to be very different. It’s about masturbation, basically, this novel. Not in a crude way, or in the way that Philip Roth would write about it. It’s an exploration of desire and yearning. It’s also, obviously, a very intimate subject matter, and the body will be involved in some way, but really, it’s more about fantasy life, and the life of images in the mind. The tone, distance, and authorial quality of the narrator will remain. It’s interested in questions of desire—what is desire; what is the difference between desire and yearning; what is the connection between the inside and the outside, the imaginary and the real.

Guernica: Are there authors who, or books that, influenced your writing? Or your interest in writing?

Anuk Arudpragasam: Yeah, definitely. I’m a very slow reader, so that has an effect. I would say about a third of my reading is books I’ve already read. I read very little that’s written originally in English. I try to read one novel that’s written in English per year, but other than that, most of what I read is in translation. The novel that made me want to become a writer was The Man Without Qualities, an unfinished novel written in the 1930s by an Austrian writer called Robert Musil. It’s amazing. I love it. It’s unfinished, in three volumes. It’s huge. It’s a modernist work. He’s introspective, and uses a lot of metaphors. He has a direct way of talking about inner life. When I read that, I realized that what I was interested in in philosophy could be better pursued through novels. I’d never seen a novel like that before.

One of the writers I love the most is a Soviet writer called Andrei Platonov. There’s a novella he wrote that’s translated into English as Soul, which I’ve read several times. He’s just a beautiful person, I feel. He writes with this real tenderness. He has a simultaneously earnest and yearning sensibility that is very conscious of the suffering of others.

There’s also a Hungarian writer whose work I love, Péter Nádas. In particular, A Book of Memories. I found this psychology of the body in his work. He discusses a lot of the corporeal elements of the inner life—gaze, gesture, posture, gait, eye contact, urination, defecation, sex, hesitation, pauses. He has an amazing way of talking about the mind through the body.

The Unnamable by Samuel Beckett. I read and reread that several times while I was writing this novel.

Guernica: You had a library of sorts from which to draw while you were writing.

Anuk Arudpragasam: Yeah. Part of why I only read one novel a year that was originally written in English is that I found these things I like, and I can spend all my time rereading them. I questioned at a certain point—why do I keep feeling this need to be reading new novels? I decided I just wasn’t going to read new novels, and to spend much more of my reading life rereading. I’ve been doing that for a couple years now.

Guernica: It’s almost like you’re getting your PhD in literature.

Anuk Arudpragasam: I would never do that because I think a PhD has a way of alienating you from what you love. I never took a class in literature or creative writing. I did feel that I needed to study texts, and to think about them, and to learn how to write them. I would, at one point, try to rewrite passages on my own that I’d read. I’ve studied, and I still study, books. I feel that that’s the only way to learn, really. Well, I don’t know. I guess people have different ways of learning. But I feel that was important for me, to study the texts, to study what I loved.

I was born and raised in Colombo, in the south of Sri Lanka. I had almost my entire education in English. My parents were from middle-class families but they did better, and now we’re part of the urban elite [in Colombo], a community I have a lot of hatred towards because of its elitism. I had my entire education in English, but in the last six or seven years, I’ve been educating myself in Tamil, and I hope eventually to write in Tamil. I feel that it will take five or ten years before I will feel that I have enough mastery of the written part of that language to feel confident with what I do in it. But that’s something that’s important to me because I feel that English is a colonial language. It’s the language of aspiration in Sri Lanka. It’s the language that is a mark of making it. It’s something I hate—I hate the English-speaking communities of Sri Lanka, India, and South Asia. It’s important to me, eventually, to write in my mother tongue.

Guernica: I understand that. It’s got to be somewhat conflicted though, since a lot of the opportunity that is available to people still in Sri Lanka and in India—at least to my understanding—requires English.

Anuk Arudpragasam: Yeah. If you want to make it to the top of, say, the business world in Sri Lanka, or India, you must be able to speak English. There are various worlds in which to speak English is to be at the top. Sri Lankan literature is all written by English-speaking people from the elite, or people from the middle class who have assimilated into the elite and who move in very small circles in Sri Lanka. They have come to occupy the role of representing Sri Lanka for people outside of Sri Lanka. I’m one of those people. I would never say that I’m not. It’s not that I’ve somehow transcended that position. Writing in Tamil, for a Tamil-speaking audience, feels like an important political position for me.