The county fair matters. In much of the rural United States, such fairs have remained financial linchpins for decades, in some places centuries, with the biggest generating millions in revenue. Even now, after their heyday in the mid-twentieth century, they are massively attended: the Erie County, New York fair brought in 1.2 million people in 2017; the Wilson County, Tennessee fair nearly 500,000; even smaller fairs often surpass 100,000 attendees.

The fair is also ubiquitous, with at least one in every state, and lots of fairs in certain states. They loom over late summer and early fall, a topic of chatter and ads on local radio, a keynote of the place and season. They are staged in sprawling, dusty fields, and they feel like many events that don’t cost much: unhurried and unpretentious. Fairs remain financially and socially vital for those with a stake in agriculture—for many rural people, the fair is the largest commercial event they will attend all year—and they still occupy a regular place on the calendar even for many people who don’t.

As spaces of political imagination, fairs are equally important. The fair’s racial scene is especially revealing. American studies scholar Trent Watts, writing in 2002, called the annual Neshoba, Mississippi county fair a “Disneyesque ‘Southland,’ a racially segregated imagining of a Mississippi town.” An array of cabins—100 percent white-owned in a county that is 25 percent black—lined the fairgrounds. Visitors could stroll past porches or even go inside for a neighborly glass of lemonade, as though they were on a white-only holiday. The only black people to be found had been hired as servants for the fair. They were not kept in the background, but rather put on display, placed with chilling precision inside this fantasy. Black visitors to the fair, though free agents, were thus implicitly made unwelcome in this space. The former state senator and civil rights activist Henry Kirksey, asked by the Associated Press about the Neshoba fair in 1992, replied: “‘When I first came here in 1975, you could count the blacks on your hand. It’s still like that. You know why?’ … He pointed to a Confederate flag hanging from a cabin.” The warning Kirksey noted was unspoken, and all the more potent for it.

During the past decade, in Ohio, where county fairs are especially prominent—all eighty-eight counties host their own fairs—the racial utopia has been punctured by some remarkably brave people who know that the fair’s symbolism matters, and who are working to erase its Confederate imagery. Their efforts remain nascent, but the attempt is nevertheless already a puncture, breaking through the skin of a body that seeks to remain enclosed. In some ways, the puncture has registered: like a virus, the fantasy has been compelled to respond actively to the intrusion, with a potent and coordinated silence: The fair’s gatekeepers steadfastly refuse to comment on racial politics, especially where the Confederate flag is concerned.

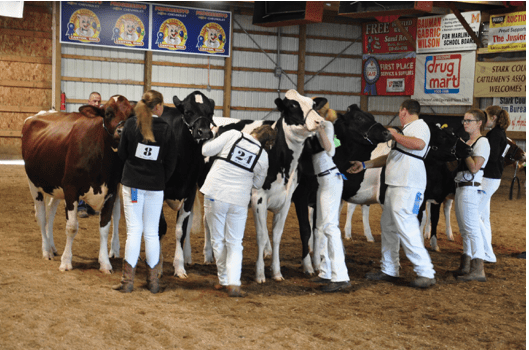

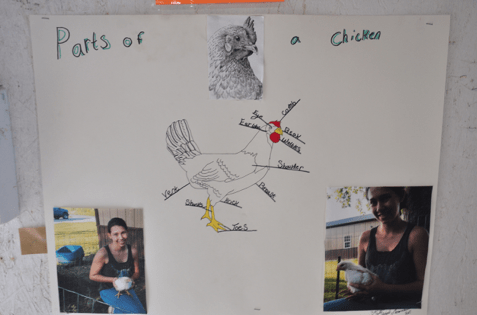

County fairs fall along a spectrum. On one end are fairs that emphasize the hard business of agriculture: farm labor, educating children through 4-H, raising and selling meat animals. On the other end are fairs that focus on the soft business of entertainment, which is off-color, deep-fried, militaristic, and profitable. Some county fairs that skew in the first direction resemble large livestock markets. Others that skew the second way are the domain of tractor-pull competitions and carnival-game-prize goldfish dying in overheated tanks along the midway. They are fun, filthy, occasionally tragic.

Others, such as the Stark County, Ohio fair that I attended this year, meet in the middle. Fairs like Stark’s, which include both agriculture and entertainment, offer a vivid, unsettling fantasy of the ways in which rural and industrial decline coincide—a fantasy with severe racial overtones. The entertainment side draws heavily on the myths generated by the farming side, including myths of virtue, myths of heritage, and myths of selfhood, all of which are transduced through the ennobling filter of cow shit. Fairgoers may pay for a belt buckle or a demo derby ticket, but what they buy is identification with a rural fantasy.

This past September, I spent three days at the weeklong 2017 Stark County Fair, which is a short drive from my hometown of Akron. My interest in fairs is anthropological—I work as an ethnographer professionally—as well as personal. I went annually as a teenager. My friend Philip’s mother enjoyed them, and she would bring her son, inviting any of his friends who wanted to tag along.

The vision of a rural utopia was powerful, though we didn’t yet recognize its depth. I recall one trip to Stark in 1995 with Philip and our friend Steve. We were old enough to take disturbed note of the Confederate flag insignias displayed openly throughout the fairgrounds, especially on merchandise and clothing. We understood that the “mammy” dolls for sale represented a nostalgia for black deferential servitude, and that the framed caricatured portraits of black children did not belong in the present. We reacted as a group of smart teenagers in an ironic era were apt to do—with the mockery that was our first line of defense, our main tactic for self-distinction. The county fair was neither logical nor warm for a middle-class Jew like me. But I lacked the insight to consider how hostile that place was to Steve. As a black teenager, he was not only an outsider there, but also a target. He passed away in 2004. Steve was a sharp observer who suffered nothing without a fully formed critical opinion, and I wish I could ask him his thoughts now. He endured it somehow.

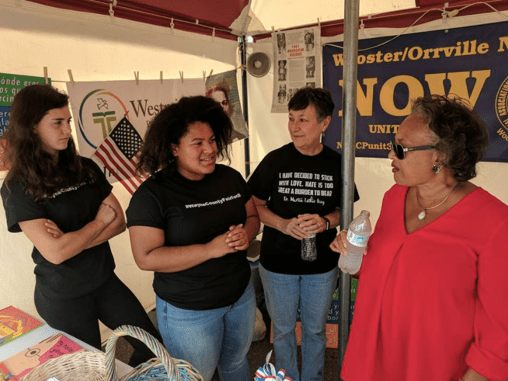

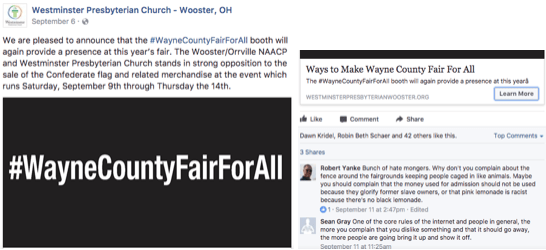

As places of racial fantasy, Ohio county fairs have not changed much since 1995. What is new is pressure to change. In 2016, a coalition that included the Wooster/Orville NAACP petitioned the Wayne County Fair (Wayne is adjacent to Stark) to ban the sale of Confederate merchandise. In 2017, a private citizens’ group began a petition drive to ban Confederate flags at the Wood County Fair in northwest Ohio. In the past few years, these efforts have become common in Ohio, largely as local actions of the Movement for Black Lives and Black Lives Matter. The Wooster/Orville NAACP, partnering with pastor Andries Coetzee of Westminster Presbyterian Church, fought the Wayne County Fair Board and jointly filed to set up a Black Lives Matter information booth at the Wayne County Fair in 2016 and 2017. One man who helped run that booth characterized it to me as an odd experience. Most visitors passed in silence. Among those few fairgoers who did approach, many did so to report their own lack of racism, as if doing so might absolve them of something.

To date, almost all efforts to ban the sale or display of the Confederate flag at Ohio county fairs have been unsuccessful. In Ohio, each county fair is governed by its own board, over which the state fair board has no authority. County boards are fiercely resistant to change, especially when pressure comes from left-leaning groups. Wayne County Fair secretary Matt Martin, explaining why the fair has taken minimal action in response to pressure, told me by email, “We have sided with what the law allows. […] It is a Pandora’s box if you will with everything that offends people.” The twenty-member Stark County Fair Board, which is entirely white (the junior fair board is also all white) did not respond to my inquiry at all. Jeanine Donaldson, an activist in Lorain County, recalls the Lorain County Fair board arguing against a ban on the grounds that black people don’t attend the fair. “There’s a kernel of truth to that,” she told the Wooster Daily Record. “We know we’re not wanted there. […] There are hidden symbols that tell us where we are wanted and where we are not.”

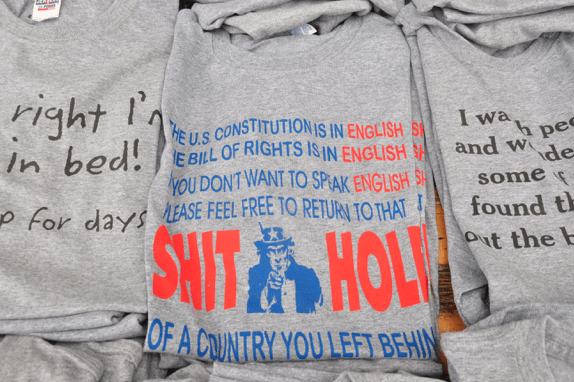

Vendors, when they would speak to me at all about the Confederate flag, offered circuitous explanations and selective historical framings to justify its presence. One jewelry seller I interviewed sold rings, belt buckles, and necklaces emblazoned with the Confederate flag, which were on loan from her nearby brick-and-mortar store. On the dirt field near her booth, tractors screamed with black smoke while her granddaughters played quietly. When I asked whether anyone had objected to her merchandise, she was initially circumspect, later offering in her own defense that “it had nothing to do with the South. It was the North and the South. There were slaves in the northern United States. Lots of slaves. And there were slaves in the southern. And then there were black people that weren’t slaves. Both places. And there were some black people that owned slaves. We’re going around in a circle here, aren’t we? […] The white people are the Confederate flag. So why can’t I have it here with all these white people?” The interview ended with her threatening to have me expelled from the fair.

Juanita Greene, president of a local chapter of the NAACP and a leader in efforts to ban the Confederate flag in Ohio, told me that the symbolic resonance of the Confederate flag differs by geography—its implications in Ohio are not the same as in, for example, Mississippi. Ohio was a Union state, and among the founders of the Stark County fair in 1849 were men who would soon fight for the north in the Civil War. Some understand the Confederate flag as part of the state’s heritage, even as a representation of the Irish saint Andrew, and not a defense of slavery. That conception, however, is at odds with the Ku Klux Klan’s decades-long association with the flag, which they adopted in the 1960s and 70s as a symbol of their opposition against black civil rights. Though decades removed from slavery, the adoption was no less a campaign of racial intimidation. “Young people are the ones who are misinformed,” Greene said, remarking on the idea that the flag could be an apolitical symbol. “They’re not afraid to use racial language. If your county is predominantly white, this is a safe space.”

Over the past approximately three years, the civil rights movement and its conservative counter-reaction have made the Confederate flag a subject of debate once more. The College of Wooster, a hotbed of student civil rights organizing in the area, even brought Bree Newsome, the activist who removed the Confederate flag from the South Carolina statehouse, to speak on campus in 2015. As Greene explains, in a city that was until recently a “sundown town” where black people could not spend the night, Wooster’s student activism has been met with a reactionary panic traceable less to the Civil War than to civil rights. Multiple white vendors, like the woman at the end of [Audio Clip 3], mentioned Newsome’s removal of the Confederate flag as impetus for a major boost in sales of Confederate merchandise.

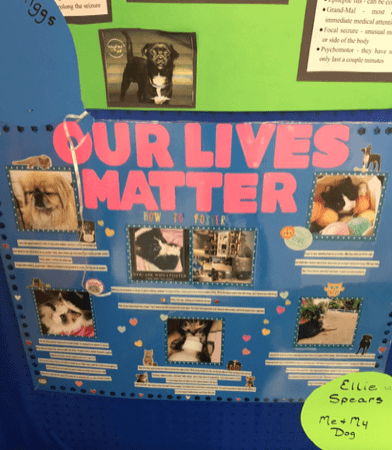

At the fair’s heart are the Marines, who seem always to face down threats to spoken English, racial pride, peace, family, work, land, and agency. The fair’s chief ritual is making these threats present, then repelling them with drama and kitsch. In a Marine recruitment trailer, one could kill virtual dark-skinned terrorists with a heavy rifle. Even the Grange Building, 4-H Hall, and Commercial Building, all places to show off prize vegetables and charming mundanities, turned out to be thick with the preservation of fantasy: One vendor told me that the NAACP’s attempts to ban the flag symbol had led to a surge in sales of Confederate belts; the NAACP’s efforts were taken as a sign to reinvest in whiteness. The construction “___ lives matter” appears on T-shirts, advertisements, buttons, at booths, and on literature throughout the fairgrounds. One young girl wore a pin reading “My City My Life Matters” and another reading “Blue Lives Matter,” and a pet adoption poster in the 4-H hall read “Our Lives Matter,” referencing the kittens and puppies pictured on the board.

On my second day at the fair, at a point of exhaustion, I saw three college-aged fairgoers, one of whom wore a campy, pro-LGBT+ “gay agenda” shirt (“Monday: be gay; Tuesday: be super gay,” etc.), and one of whom was black. They appeared like a mirage—at no other point did I see anyone who looked or dressed remotely like them—and I was so numbed that I did not at first recognize them as real beings, and stumbled trying to introduce myself as they walked past. I had to find them again later. “People give us looks,” one of the women told me, when we finally spoke. “We get looks a lot. You know, it’s just constantly the looks and not really saying anything but showing it by their actions.” “I’m a lesbian,” another woman added, “so sometimes I’ll dress more boyish or whatever. When I did have a girlfriend, and I was holding her hand, I got so many looks. It’s just part of the life.” They were 17 or 18, old enough to walk against traffic but young enough not to fear doing so.

The fair has endured, but it has not evolved. For years, the fair’s attractions have offered the same amusements, the same jokes, the same prizes, the same artifacts, all day, for several days. The monotony is pleasant, if numbing. One fairgoer I spoke to noted that the difference between a $6 fair ticket and a $63 ticket to Cedar Point, the world-famous amusement park in nearby Sandusky, accounts for why the county fair has remained so popular. It is a magnet for community of a certain kind, easily accessible, and much of it is uniquely charming. Events at the fair that still draw crowds include a demolition derby, a smattering of live musical performances (Stark’s big concert attraction in 2017 was Charlie Daniels, now 80 years old and a pro-Trump conservative), as well as a few climaxes of livestock judging and selling. The fair offers a stable fantasy of what the world might be like, until it moves to the next town.

The world outside is not far off, however. The Stark County fairgrounds are less than two miles from two sites of national importance: the William McKinley Memorial and Library, where the twenty-fifth president is entombed, and the Professional Football Hall of Fame, neither of which is represented in any way at the fair. (Fairgoers are visibly loyal to the Cleveland Browns, a team that won only one game the previous season, and would win none the next.) The city of Canton is semi-urban and poor, while the surrounding townships are rural and poor, and 21 percent black. R&B singer Macy Gray was born there, as was Greek-American NBA player Kosta Koufos; the O’Jays formed in the city in 1958. None of this plurality is noted or reflected within the fair, but it is in ways both figurative and literal just outside the gates.

I spoke with Andre Bulluck, who owns Dre’s Place, a Georgia barbecue joint that travels to county fairs around the country. Bulluck was one of only a handful of vendors of color I saw at the fair. One knickknack booth was run by a Peruvian man, and another by two men from Africa, none of whom wished to be recorded or photographed. Bulluck has a culinary degree, and his restaurant has been featured on the Food Network, but the fair has proved a difficult space to penetrate despite his credentials. “It’s always interesting being a minority person out here,” he told me. He tossed a slab of pork onto his weathered red grill, slathering it with sauce. “We don’t have a big following of us directly in the fair community because they don’t let us in. I fought hard. I had to fight for the last ten, fifteen years. … Let’s see, 2006 … I’ve had some bouts. They don’t want you here really sometimes, because you affect people’s money when you come in with a different game […] When people been here a long time, they set up the fairs for people that’s been here forty, fifty, sixty years.”

The fair’s intransigence is nothing new. “People have power they don’t want to relinquish,” Greene, the NAACP president, told me on the phone. I had called her from the fairgrounds, in a moment of panic and confusion. The intensity of this desire to hold onto power is perhaps why the fair’s symbolism has continued to propagate, Greene explained. She told me a series of stories about racial subjugation in Wooster, where “people have learned not to upset the cart.”

The lessons, warnings really, hung in the air. Symbols matter. I could see them on the wall of a T-shirt booth near where I called Greene. This is where her labor of dissent begins, from within the fair’s hermetic interior. But a great burden remains: it is hard to wake people from their fantasies.