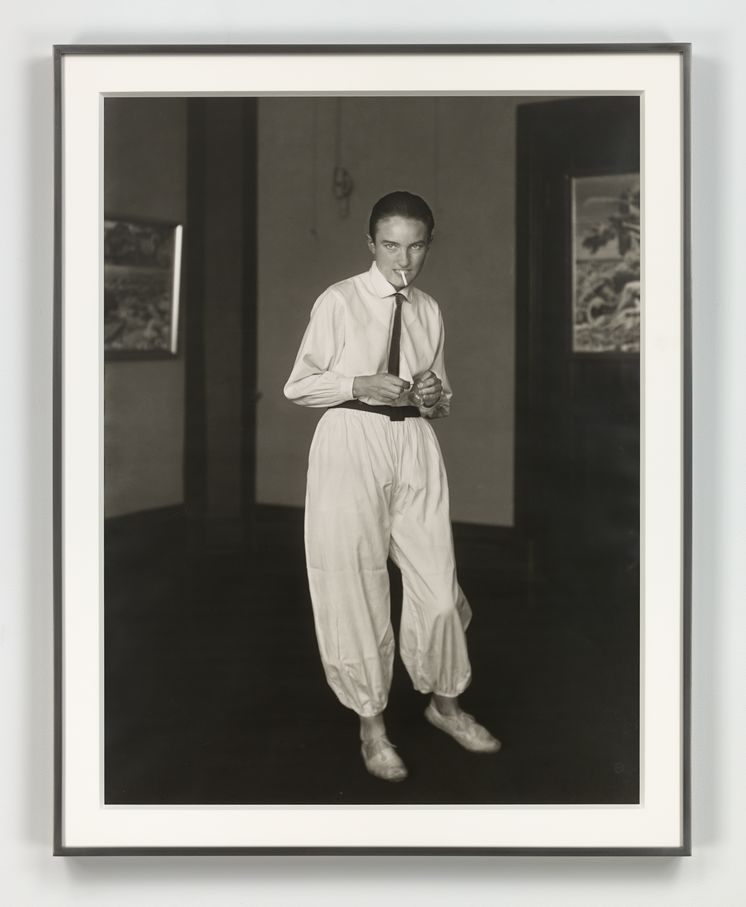

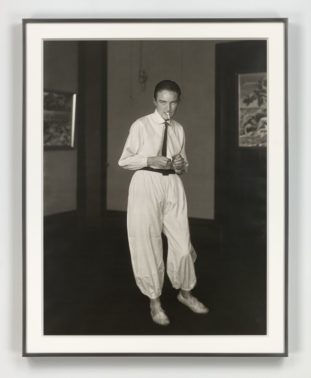

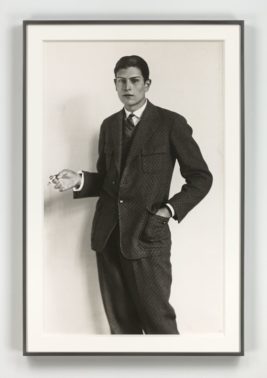

I remember—always with the same strong feeling of clarity—the first time I saw a collection of portraits by the German photographer August Sander. It was a couple of summers ago in New York. I had spent a few days shrink-wrapped by anxiety, my mind blurred and alienated. I walked past the gallery and felt a pull, an invisible open signal, and so I entered. About ten black-and-white works, taken in the early 20th century, hung eye-level on the wall, each presenting a stranger with a face that I instantly recognized. The alluring painter’s wife, knowing what she does about sexual desire, in her loose pants. The young secretary with her hunched shoulders and defensive glare. The high school student, in the wrong clothes and the wrong life. The arrogance and abject denial of the soldier, under his helmet and in front of his land. All of them very different, but each with a simple stare, their inner selves resonating through these one-dimensional representations of their long ago lives and into mine. In their image, I began to regain a sense of my world.

What made his subjects look at him like this? In his self-portraits, Sander, born in 1876 in a small village near Cologne, seems shy and slight. He discovered his medium by chance, and took an apprenticeship. His obsession with personality and typology led him to begin work on a lifetime project, “Faces of the Twentieth Century”, in which he planned to photograph as many Germans as possible, in the most realistic terms, and categorize them into groups: “The Farmer,” “The Skilled Tradesman,” “The Woman,” “Classes and Professions,” “The Artists,” “The City,” and “The Last People.” During this period—post World War I—this was not seen as presumptuous, elitist, or racist: the idea of being able to detect, for example, criminality via physical appearance was taken seriously, a sociological gesture for the community.

Alongside this methodological and reductive approach, Sander described his work as a search for truth, a reach essential for a greater understanding of humanity. His academic words belie an exalted, mystical tone: “All things that happen have their appearance, or ‘face’, and an event’s total appearance is its physiognomy,” he said in a 1931 radio lecture, adding, “We know that people are formed by the light and air, by their inherited traits, and their actions… A well-known poem says that every person’s story is written plainly on his face, although not everyone can read it. These are the runes of a new, but likewise an ancient, language.” Objectifying his sitters was impossible: seeing them, understanding them exactly for who they were with no judgement, was crucial to his process.

Uptown, near the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Hauser & Wirth Gallery is currently showing forty portraits, all taken between 1910 and 1931. These specific works were among those re-printed in large-scale format by Sander’s son Gunther, for an exhibition “Men Without Masks: Faces of Germany 1910 – 1938” at the Mannheimer Kunstverein in 1973. That show was an effort to revive discussion around his father, who despite finding widespread popularity with his first publication, “Face of Our Time” in 1929, had to leave Cologne after the demise of the Weimar Republic. While some have since argued that Sanders’ concept of categorization encroaches too much with the far left’s classification system, the Nazis saw it differently: The book was removed from circulation and the original plates destroyed. New work, much of it from “Faces of the Twentieth Century” was later lost in a fire. His son, Erich, died in prison after being put away for his political resistance. Sander never returned to portraiture, and died in 1964.

Among our contemporary masters, he is considered a genius who invented portraiture, but his reputation doesn’t extend much further than that—a problem singular to the medium, explained Olivier Renaud-Clément, who curated the show. Hauser & Wirth recently announced their worldwide representation of the August Sander Family Foundation, a deliberate move to push Sander’s photography into its rightful spot in the art marketplace. “Why would you differentiate a good drawing by Louise Bourgeois from a good photograph by Sander? This is still happening,” said Renaud-Clément.

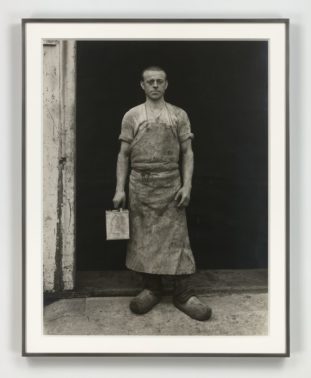

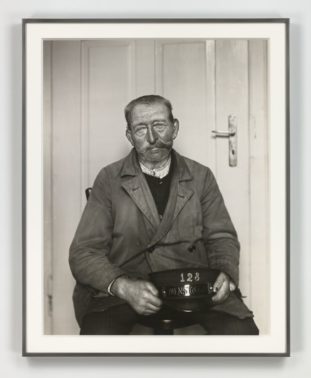

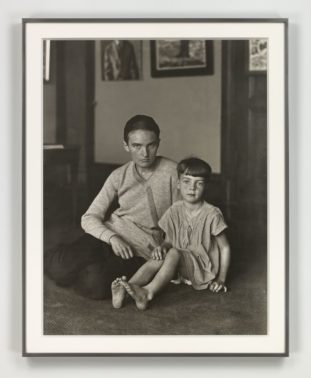

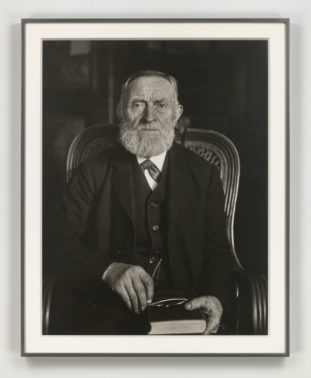

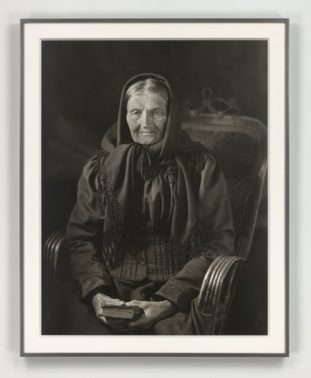

Visiting this new exhibition—this time open and prepared, surrounded by the throng—I found the same locking of the gaze and intense stillness of these encounters. On the second floor is the full “Portfolio of Archetypes” of the people of Stamm-Mappe, the first set that Sander photographed using his conceptual parameters. Elderly inhabitants from his home village, most of them laborers, farmers, peasants, their lives beginning to be imposed upon by industrialization, some wearing new, uncomfortable suits, others in traditional clothing; many grasping bibles, burning in their clear hands. Their grasp may be antiquated, but the conviction in their fingers is the same as yours. Downstairs, the porter’s suit may be old fashioned, but the fraying at the edge of his jacket is not. The varnisher is framed by ancient walls and rendered whole by the evidence of years of craftmanship. Our painter’s wife, here with her daughter in their modern home, reveals herself as a woman who will confront anyone who might consider her progressive values detrimental to her parental love.

Taken around 1926, this image identifies the cultural shifts and divides of a country experiencing the sudden but vanishing artistic bloom amid democratic idealism: political perhaps, but her pose, like all the others, suggests possibility, a sense of being seen. He allows his subjects to identify themselves in fundamental ways, and in these faces we spy not just the inevitable signs of class, labor, heritage, education, or privilege, but we see those in our lives whom we miss, regret, adore, despise, fear, and cherish. Truth is unmovable, unchangeable, and with Sander’s eye, captured in light and air.

August Sander runs through June 17, 2017 at Hauser & Wirth on 69th Street.