Every book consists of a kind of migration. It begins in one place and ends in another. Prior to publication, it also undergoes a journey of revision: the text must travel from its initial form to its finished state.

Javier Zamora’s memoir, Solito, tells the story of his journey from El Salvador to the United States when he was nine years old. In a harrowing account, he describes vividly the dangers that waited at each border crossing, from the barbed wire and cacti and La Migra to the brutal sun that beat down from above.

In the course of revising Solito, Zamora switched the perspective from third person to first person. He went from writing about that nine-year-old boy to becoming that boy again. I asked him if this change was more of an editorial decision or a therapeutic step in the processing of his trauma. His answer rang loud and clear: “It was both.”

— Ben Purkert for Guernica

Guernica: So you originally wrote your memoir in third person and then you switched it to first person, correct?

Zamora: Yes. And the reason has a lot to do with therapy.

I spent so long trying to hold this story in. I didn’t want to write this book. I was on a fellowship at Radcliffe and I was supposed to be writing poems. But the poems weren’t coming, so I was frustrated. And this was in 2018, when every single headline was about the caravan, about Central American children at the border, about unaccompanied children who were incarcerated. It was very intense to take in. I would drink heavily and run my body down. Then, near the end of the fellowship, I decided to try prose. I had to. I was tired of reading nonimmigrants writing about immigration. I needed to put my voice in the ring. But I was still cloaking myself. I was distancing myself from my own story. That’s where the third person came in.

Guernica: What compelled you to switch? Was it more of an editorial decision or a therapeutic one?

Zamora: It was both. One happened before the other.

Guernica: How so?

Zamora: I started writing this book in April of 2018. I had never written prose before. It was a marathon! I was used to sprinting with poetry. But this was a different kind of discipline, a more physical labor. And I was spending hours typing away, which was therapeutic in a way. I was remembering. But I wasn’t reliving it yet.

Then the fellowship ends, and I’m still writing it in the third person. I meet my agent, and he tells me to keep writing. So I do. Then I start writing the boat scene, and that scene is predominantly present-tense in the first person. And my agent gets back to me and says, “These are the best pages you’ve written. Can you do more like that?”

At first I reject his suggestion. I’m thinking, “Fuck no.” I have to protect my artistic vision, and all that stuff. But then I have a chance meeting with a therapist. It was a Monday or a Tuesday at noon, and I’m sitting at a bar on my third martini with my computer out, attempting to write. But I’m not writing shit. And this therapist approaches me out of the blue and asks if I’m doing okay. Finally, she gives me her card and says, “I think I know someone who can help you.”

That’s how I met the therapist who changed my life. During our second or third meeting, she asked a question that had a huge impact on me, and on the book. She said, “What would it look like if you really talked to that nine-year-old kid? What would happen if you welcomed him into the room?” It shifted the whole project. I revised everything into first person after that.

Guernica: That’s so powerful. I wonder if this happens often — if memoirists often start in the third person when writing about trauma and then, through processing, move into the first.

Zamora: After you survive something, your brain does everything possible to keep it hidden. And hiding oneself in the third person, that’s one of the strategies I used.

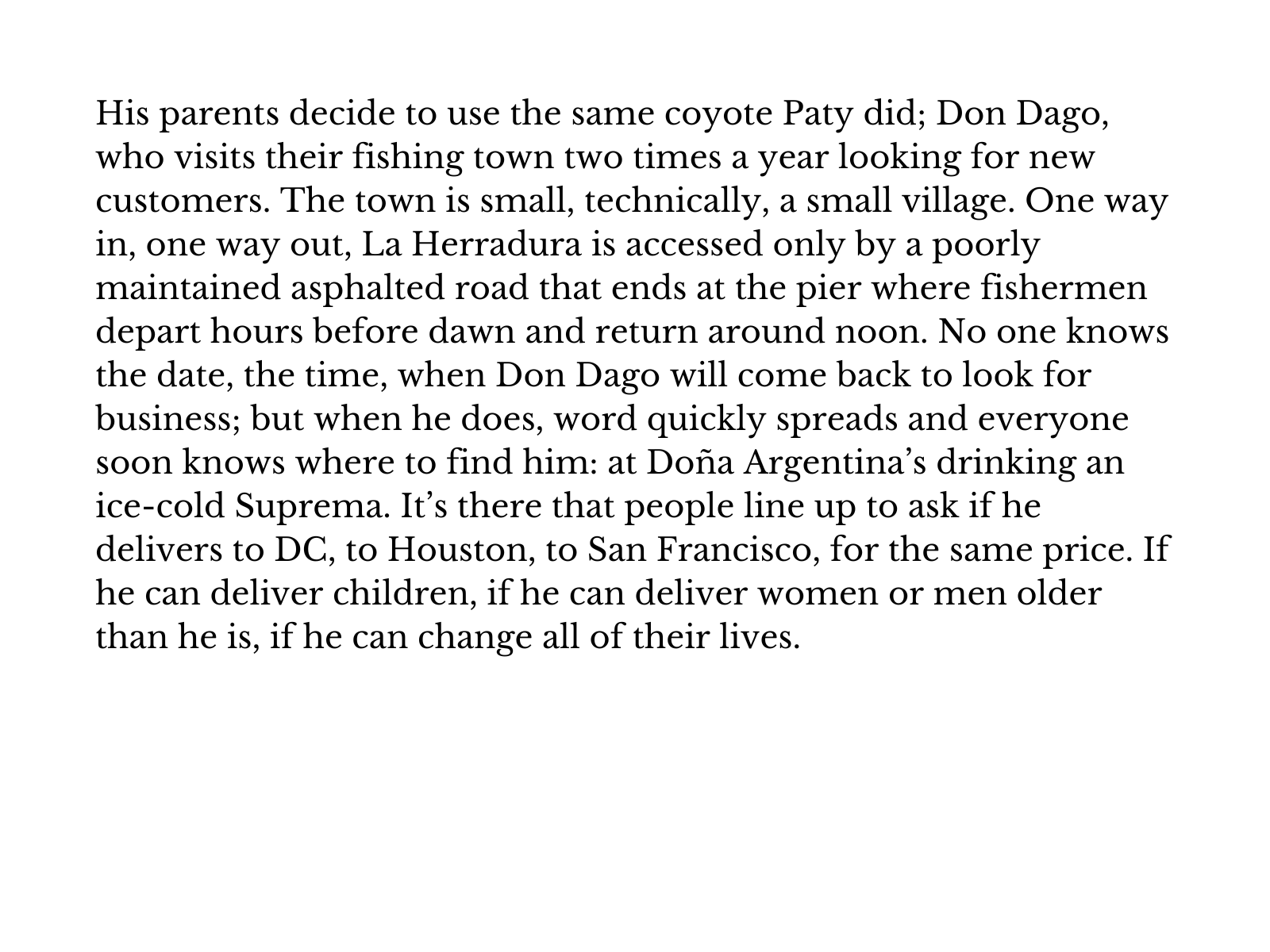

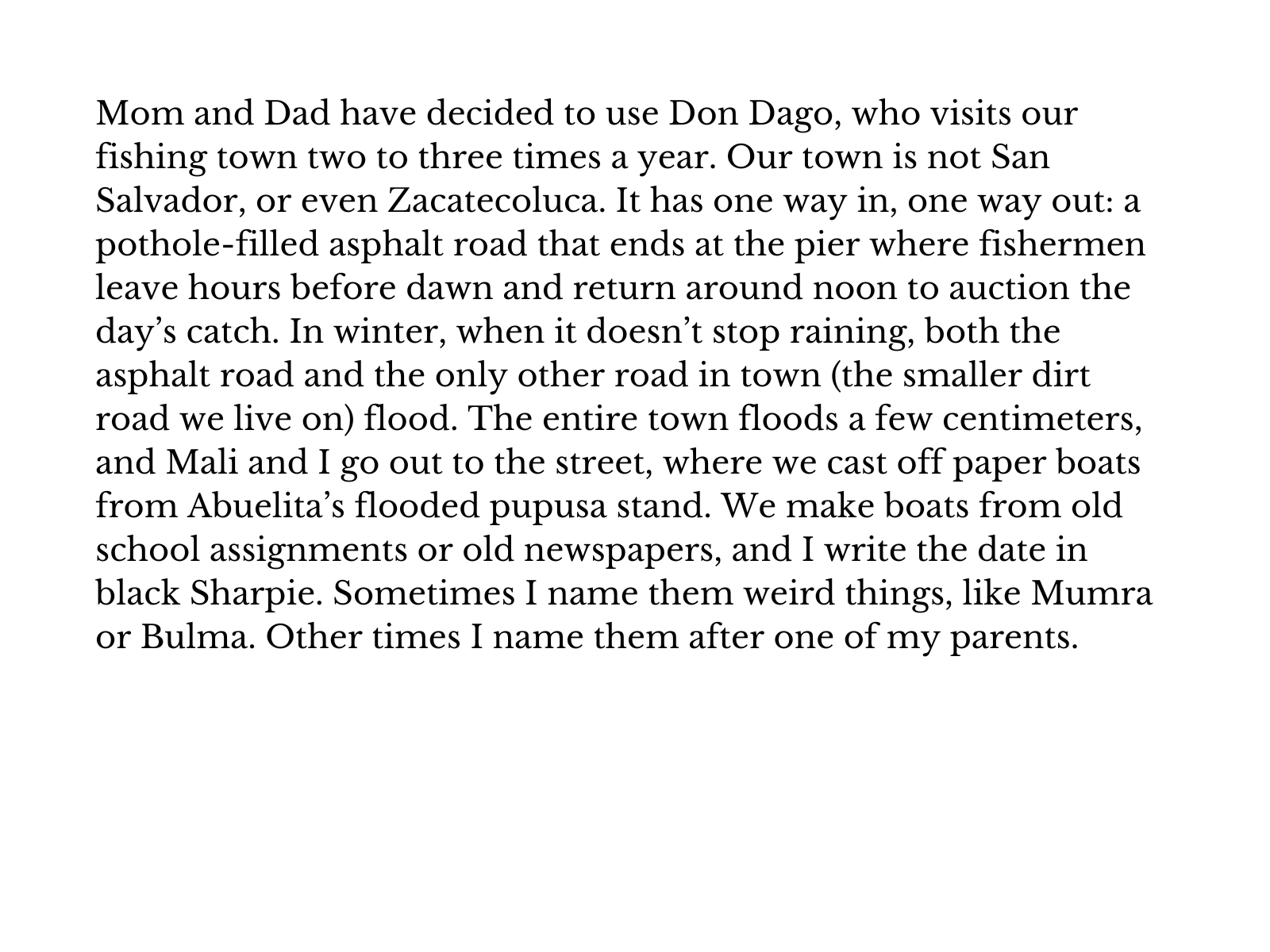

Guernica: Comparing the two drafts above, I’m interested, not just in the perspective shift, but in the details you’ve added. You refer to fish as the “day’s catch,” and you mention the flood risk, which isn’t included in the first draft. It’s like your word choice is hinting at the treacherous journey to follow.

Zamora: That’s so interesting. I hadn’t thought of it that way. The flooding is something about home that I genuinely miss. Every time it rained, my town would flood. As a little kid, I’d want to get my feet wet, and my grandma wouldn’t let me for fear of fungus or some other disease. Those rainy days were epic.

Guernica: Speaking of your home town, it’s interesting to me that your book devotes so many pages to situating the reader in El Salvador before the migration journey begins. It’s such a contrast with the abruptness of the book’s ending.

Zamora: Thank you for noticing that. I’ll begin with the abruptness. I wanted the reader to feel the same thing that many immigrants feel, that sense of having strained for so long to cross a border and suddenly once you arrive, you’re like, “Wait, this is it? Was it really worth it?” I needed the reader to experience a similar shock.

Had I been older when I came, maybe thirteen or fourteen, the book would be remembered very differently. But because I was nine, I was still in a hopeful state. Everything around me was beauty. Going back to El Salvador now, I’m still struck by how beautiful it is. The mot-mot, that’s our national bird. We had those in my backyard. And we had aracaris, which are a type of toucan. Two types of green parakeets. Five types of hummingbirds. Anyway, I wanted the reader to see some of that, and appreciate what I was leaving behind. Obviously, I wanted to come and be with my parents, but I was terrified of leaving my grandparents, my community, my friends, and the beauty too.

Guernica: What were the hardest parts of Solito to write?

Zamora: Funnily enough, not the trauma chapters. It was the beginning. If I were to be unhappy with a section, it would be chapter one. But the border crossings — my brain remembered that so vividly, so it was easier to write. All those details, whether the dust or even a particular lizard. I remember all that. For some earlier parts, it was hard to recall. For example, for the Guadalajara section, I had to look back at the weather reports and soccer schedules in order to write those scenes. It’s fuzzier.

Guernica: The book blends Spanish and Caliche (Salvadoran slang) in with English. How did you decide which language was best suited to which part?

Zamora: Writing a book of poems helped me with this. It made me really purposeful about which language I use and when.

We’re at a moment in the United States where we need to recognize that are a lot of fucking Salvadorans in this country. We are the second biggest immigrant group outside of Mexicans. We just passed Puerto Ricans, I think. And yet there isn’t much Caliche out in the world — or at least not when I started writing the book.

When I switch into Caliche, it’s because I need a word that only exists in El Salvador. And secondly, there were things told to me by my parents, by my pseudo-family, by coyotes, and these things only ring true in the language they were spoken or felt. Translating them would do a disservice to the emotional truth of those things.

Guernica: Given that you wrote the memoir from the perspective of a nine-year-old boy, you’re somewhat limited in how you discuss certain subjects. Was it challenging not to delve more deeply into the political history of El Salvador, and specifically the US involvement in the civil war there?

Zamora: That’s a great question. Nobody has asked that.

The immigration machine, the monster, has changed from the time I immigrated in 1999 to now. In the present day, I would have to represent myself as a nine-year-old. There are currently detained one-year-olds and two-year-olds in the immigration court who are asked to represent themselves. As a kid, I didn’t even understand what politics was. And in that regard, the book is political in and of itself. I never knew about the civil war until I was eighteen. In my country, there is war denial to this day.

Guernica: In the US, it seems like meaningful progress on immigration remains more elusive than ever. Do you think your book has the potential to change minds, and maybe change policy?

Zamora: Hopefully. But I’m not confident. [Laughs] I’ll tell you an anecdote that will maybe get me in trouble.

I had something lined up with The New York Times, and it was scheduled to run after the November midterms. In hindsight, I think what happened was that the Times editors thought there was going to be a red wave, and immigration was going to become a hot topic.

Anyway, a few days after the midterms, the editors told my publicist, “We don’t think immigration is as important anymore.” Or something like that. And this is what infuriates me, because we need to stop treating immigrants as a story [and start treating them] as human beings. Until people in power — and I’m not only talking about politicians but also people in publishing, in journalism, in media — stop looking at immigration as an opportunity for clicks and advertising, and look at it as a truly humanitarian crisis, then shit won’t change.

Guernica: Right.

Zamora: Ultimately though, I didn’t write this book to change politics. I needed to write this book for myself. We have that cliché about walking in other people’s shoes. I needed to walk in my own shoes. I had to relive my past, just in order to heal. And, as a result of that process, my readers get to see that trauma, because I’m inviting them in.

But I do think the political potential is there, because the book is written from a child’s perspective, you know what I mean? It’s much easier to dismiss an adult than a child. That’s why the US immigration system is so obsessed with children. We only ever want to save the children. Maybe that will be an entryway into someone’s mind or heart. I don’t know.

Guernica: Your book has a blurb from Sandra Cisneros on the cover that reads, “I have waited decades for a memoir like Solito.” It’s such a powerful endorsement, and it also implies a great deal of pressure. In the process of writing this book, did you feel like you were carrying a mantle of sorts?

Zamora: Again, I’d say that publishing my poetry book, Unaccompanied, helped me to cope with that. When that book came out, I still thought it was possible to control a book once it’s out of your hands. I told myself, “I’m going to represent us. I’m going to represent everything about us!” But then I worried about throwing my government under the bus. Was the US government going to come after me because I’m still undocumented and I’m talking shit about them?

Now I think I handle it differently. I understand that, once a book is out, it’s on its own train tracks. I just bought the subway ticket. And now it’s on its way.

Guernica: You’ve mentioned your poetry book a few times, and I’m curious if you could speak to this trend of poets publishing in prose. What do you think is motivating this move across genres?

Zamora: I’ll give you two answers. One answer is the academic answer and the other is the ratchet answer. The ratchet answer is that we want to eat. The current economic framework for poets isn’t working. It’s not feasible. I’m not saying prose is much better, but it does pay more.

The academic answer is that, as poets, we are naturally skeptical of genre and see that those divisions are mostly bullshit. Why be tied down to one genre for the rest of my life? It makes no sense. If you look at Latin American writers, it’s rare when a writer only does one thing. You either start off as a poet or a journalist. Then you write your novel and your short stories. Maybe you eventually come back to poetry or journalism. But you do it all. You’re allowed to do it all.