Walking up to the Minneapolis VA hospital for the first time, I feel a long-forgotten sense of dread and shame. I’ve been out of the military for fifteen years, and I’m not in uniform, but it’s the same feeling that I used to get walking up to any chow hall or military building on the Balad Air Base in Iraq. Dread because I hated always having to be on guard and alert in case I passed an officer and needed to salute. Shame because often I’d be thinking about something else, pass an officer without saluting, and then get called out by the officer for not respecting rank and not paying attention to my demeanor or my surroundings. Once, outside the PX — the makeshift store where we bought junk food and deodorant and CDs — an officer yelled at me for several minutes while I stood in a position of attention and tried to imagine what would happen if I just took off in a dead sprint away from him.

I am early for my appointment, so I spend ten minutes just wandering the halls. I find the chapel and the cafeteria, the emergency department and a lobby of people waiting for X-rays. I pass a woman who can’t find her husband. Another woman is knocking on the door to the single-user restroom, asking if her husband is in there. He is not, but someone else is. On my way back toward the main entrance, I pass a couple just as the wife turns to her husband and tells him to use the restroom while she pulls the car around. I smile at both of them, but they don’t notice me at all.

I am at the VA to participate in a research study called “Service and Health Among Deployed Veterans” (SHADE). The purpose of the study is to learn more about the long-term impact of pollution exposures on the health of veterans who served in Iraq, Afghanistan, and five other countries after Oct. 1, 2001. For years, I’d been reading reports and news stories about veterans coming down with a whole range of unexplainable symptoms after serving overseas. Veterans contracting sinusitis or asthma, or getting ulcers or open lesions on their skin. Vets who were perfectly healthy before being deployed but returned barely able to exercise without getting winded. Vets dying of rare cancers or contracting respiratory illnesses like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which causes coughing and wheezing and makes it difficult to breathe. Some vets started to point to the open pits used to burn trash on military bases as the culprit. But when they filed claims for treatment and disability benefits with the VA, they were denied because of the lack of proof that burn pits were making them sick. It also took years for some of these symptoms to materialize, forcing some vets to wait for approval for their claims before even setting up appointments with the VA. People started calling burn pits my generation’s Agent Orange.

Reading all this information about burn pits over the years, I started to wonder if my own mysterious ailments were connected to my time in Iraq. When I started getting headaches on a regular basis in graduate school and was told it was just stress, I thought about the burn pit I served near and the smoke I’d seen wafting from it. When my sinuses started flaring up, I wondered if something I was exposed to gave me chronic sinusitis or something worse. I had a CT scan done on my ribs and was told I had a benign fatty tumor—nothing to worry about, but still uncommon for a 26-year-old. I couldn’t help but blame my military service. Part of me wanted to believe that these concerns were psychological, my mind jumping to the easiest conclusion. But another part of me worried that it was something more than that, that my paranoia was valid and real. Then a friend posted a news story about her childhood friend, a Minnesota National Guard veteran named Amie Muller, who served in Iraq in 2005 and 2007 and died at thirty-six, nine months after being diagnosed with Stage III pancreatic cancer and ten years after she returned home. Muller believed she got sick from exposure to the open burn pit at Balad Air Base, the same base I’d served at from 2003 to 2004. I didn’t know Muller but I knew the place she had been. Reading about her made the controversy feel closer than ever before. It felt real.

Just inside the VA’s main entrance, I locate the clinic where I need to be and check in at the receptionist’s desk. After about five minutes of waiting, I look up and see a young woman step out from behind the front desk and call my name. She introduces herself as Maddy, shakes my hand, and asks me about the weather as she leads me down the hall. She doesn’t have a lab coat or a clipboard. We don’t enter a fancy conference room with recording equipment, potted plants, and natural light pouring in through the blinds — my vision of where a government-funded scientific study might take place. We step into a small, windowless room with a computer and a couple chairs and a tiny sink in the corner with a clock above it displaying the wrong time.

I sit in the chair against the wall and clamp my hands between my knees to stop them from shaking. We go through the consent form together, and then, after recording my height, weight, and pulse, Maddy starts asking me about my military history. She wants to know where I served and how long I was there. I tell her about Balad Air Base, where I spent most of my time while I was in Iraq. She types this into the computer, then looks over at me and asks the question I’ve been expecting.

“Was there a burn pit there?”

We called it The Dump. It was in the northwest corner of Balad Air Base. When I first arrived at Balad in May 2003, near the beginning of the American occupation of Iraq, The Dump was little more than a growing mound of trash. As the weeks went on and the number of troops at Balad Air Base grew, so did The Dump. By December of the same year, the single mound had grown to become a maze of heaps set aflame. The Dump would eventually grow to span more than ten acres and burn more than 200 tons of trash a day.

One day that December I was tasked with escorting a group of Iraqi contractors to The Dump to repair a section of the perimeter fencing. Someone had been hiring kids to crawl under the fence and steal some of the more valuable items from The Dump, and a soldier at a guard station had shot one of the kids in the leg. My job was to supervise the workers and make sure they did a good job, so no more kids got shot. It seemed like a cruel trick — to ask the Iraqi people to fix a problem the US military had created — but it wasn’t my job to question it. I just nodded when the sergeant in charge gave me my orders.

After the workers finished patching up the fence, they took to scavenging through the trash in The Dump and making piles of items they wanted to take with them. They brought back Christmas wreaths and old truck tires and empty powdered-Gatorade tubs. They carried over broken box fans and aluminum cans and even photographs they found mixed in with everything else. They wanted so many of the things we had just tossed away. Watching them make their piles of our trash, I felt embarrassed by all the waste we produced, how we could toss away so much when many of the Iraqi people outside the base had so little. I’d like to say I thought twice about all the unnecessary things I bought at the PX after that, but I’m sure it isn’t true. I still bought CDs and junk food and magazines that eventually ended up in The Dump.

When it came time to tell the workers that they couldn’t take any of the trash from The Dump, I asked one of the other soldiers do it. I didn’t have the heart to tell the workers that the treasures they’d found were all supposed to be burned.

At the time, I didn’t recognize how much of an impact The Dump had on the rest of the base. The lot next to our tents was covered in this finely ground sand — powder really. It was unlike any sand I’d seen before. Every time a vehicle would leave the motor pool, where we parked our Humvees and trucks, it would kick up clouds of dust that wafted over the tents where we slept. I’d find the sand in my boots, inside the folds of my sleeping bag, in between my toes, and in the crooks of my arms. During the summer when we slept with the tent flaps rolled up, I’d wake to find a fine layer covering every inch of my sleeping area. I would joke to the other members of my platoon that the sand was burying us alive. I found this genuinely funny at the time.

“It’s like walking through ash,” Danny, a member of my platoon, said once as we kicked our way across the motor pool. Danny found the sand interesting. He had taken to collecting it in miniature Tabasco sauce bottles that came in the MRE (Meal, Ready-to-Eat) packets. He showed me four tiny bottles in the palm of his hand. I pinched one between my thumb and forefinger and stared at the sand inside. I admitted to him that I was also a little mesmerized by the sand, but I didn’t tell him that I’d taken to picking up handfuls and letting the grains fall between my fingers as I walked across the motor pool, just for the sensation of feeling the powder against my skin. It made me feel light and carefree, like I could float away at any minute.

Not once did it cross my mind that the sand might have been ash from the burn pits at The Dump. I just assumed that the sand in Iraq was different. This ancient Babylonian sand ground to powder from years of being trod upon.

It wasn’t until after I returned from Iraq that I found out what all was tossed into those burn pits at The Dump. Plastics, Styrofoam, paint, chemical waste, unexploded ordnance, used needles. Even amputated limbs. It was all soaked in diesel fuel and lit on fire, and from those fires pollutants like benzene, dioxins, and other carcinogens were released into the air and carried across the base. We breathed in these pollutants walking to the chow hall. We breathed them in while driving around base. We breathed them in while standing guard, while staring at all that ashy sand, while dreaming about our families and friends, while thinking about going home.

When I was five, my father was burning trash in the center of our farm and fire escaped the burn-barrel and leaped across the yard. The fire burned the tall grasses near our house and the brambles and young trees in one of our sheep pens. Our local fire department was called, and while they put out the fire I waited inside our house and watched my mother cry. I wanted to look out the window, to see what the fire was destroying, but I couldn’t look away from my mother. She was afraid that the fire would take away everything she and my father had worked so hard to create. She had no real way of knowing what would be destroyed.

The fire didn’t cause any major damage — just enough for us to notice. In the days after the fire, I walked around the scorched yard and examined what had been ravaged. I walked over all the charred grass. I ran my hand over the blackened baseboards of one of our outbuildings, the one half-full of junk. I stopped in front of what used to be a beautiful, mature green ash tree with two trunks. The fire had burned away the branches and licked out the insides of one of the trunks. I stuck my hand inside and wiggled it around. There was nothing there. It was hollow, just a husk. But the other trunk of the tree survived. In the years after the fire, it continued to grow branches and leaves, while the destroyed trunk remained a blackened shell.

I hated seeing the tree like that, half of what it used to be. But something about its transformation mesmerized me. As a bookish kid, I knew what I was supposed to see in that half-destroyed tree. Perseverance. Rebirth. Beauty in the scarred. I didn’t really see any of that. Instead, I stared at the two halves and wondered about the power of fire, how some things get caught in the flames while others escape seemingly unscathed.

I keep thinking about how risky it can be to simply do a job, about all these hazards that come with mere work. Fire and fumes and toxic mold. IEDs and stray bullets and dust. I think about the jobs I’ve had — paperboy, janitor, farmhand — and all the different ways those jobs could have killed me. Getting run over one dark morning while tossing a newspaper onto a stoop. Slipping on a newly waxed floor. Being dragged behind a wild horse while out tending to the land. (That actually happened to one of my distant relatives). There are so many ways to die while working.

I was 23 when I arrived in Iraq, young and naïve and unsure about so many of my abilities as a soldier. Soon after being deployed, I figured out that the easiest thing to do was to surrender my body to the Army as completely as I could. I listened to the sergeants and officers who told me what to do, where to be, and how to act. I saluted them when I noticed them on the base, and stayed on guard for when I might need to do so again. I listened when the staff sergeant talked about IEDs and the enemies beyond the wire who were trying to harm me just for being an American soldier. And I knew enough about “friendly fire” to know that I could die at the hands of the soldiers I was serving with. For the most part, the media and my military training prepared me for what to expect in Iraq.

It’s the unforeseen hazards, the dangers I couldn’t predict, that haunt me now. Every time I read another story about a 9/11 first responder dying from some cancer linked to the World Trade Center collapsing — like the burn pits, it had been doused in jet fuel and set alight — I think about how my own naive trust in the military overpowered my concerns about the occupational hazards associated with doing my job. I was too young and inexperienced to imagine the risks of living and working near a burn pit, let alone the harm the burn pits did to the bodies of Iraqis who lived nearby. It wasn’t in the media; it wasn’t in my military training. If I had known, I might have thought twice about marching through all that dust and smoke without a mask, scooping up handfuls of that ashy sand. Maybe I would have paused a little bit before so completely surrendering my body to an organization that talked a good talk but, ultimately, saw me the same way it saw everyone else, my fellow soldiers and the Iraqis who surrounded us: as disposable.

Maddy hands me an information sheet about the VA’s Airborne Hazards & Open Burn Pit Registry. I already know about the Registry. I heard about it in 2014, when it was first created for service members to document exposures and report health concerns, but I put off completing the questionnaire for the Registry for five years because I was afraid of going down an unhealthy path of obsession. There was still so much unknown about the effects of exposure to burn pits, and I didn’t want speculation to take over my life and lead to a quest for someone or something to blame. Plus, I didn’t fully trust that the military would make things right.

If I didn’t complete the questionnaire, I thought, I could remain oblivious to the effects of the burn pits and avoid years of anxiety over thinking I’d been affected. To register something is to know it, to comprehend it, to notice something about it, and I wasn’t sure I was ready to start noticing just yet.

But something changed over time. I couldn’t easily avoid burn pits, even if I wanted to. I kept hearing about them. More stories of soldiers getting sick. News articles about advancing research on chronic respiratory illnesses. Future US President Joe Biden acknowledging the link between burn pits and his son Beau’s death from brain cancer in 2015. Jon Stewart signing onto advocacy efforts to raise awareness about illnesses related to burn pit exposure. Finally, in 2019, before my visit to the VA, I consented and sat down in front of my computer to complete the Registry’s questionnaire. For a while I just stared at the number of people who’d registered before me — 180,750 — and read the factoids on the website. Eventually, I clicked on the questionnaire’s link, took a deep breath, and started answering questions.

The questionnaire asked about location-specific exposures in Iraq and Kuwait, if I was involved in trash hauling or burning, if I knew who ran the burn pits, and how many hours smoke or fumes from burn pits entered my work or housing site. I don’t remember the smoke being distracting or so thick I couldn’t see, but I remember often walking across our company’s section of base and seeing little fires everywhere. There were fires in common areas outside a cluster of tents. There were fires outside the outhouses we built because we had to burn our own shit and piss. Looking up, if the sky was clear, I could see smoke drifting up from somewhere off base, wafting up from the horizon and over our tents while we slept. It seemed perfectly normal to see smoke every day in Iraq. Smoke was everywhere. But why was that?

The questionnaire tried to get me to think of other exposures to airborne hazards, too, things outside of Iraq. It asked where I lived the longest before I was 13, which got me thinking about the trash barrel on the farm I grew up on and everything we burned in it. It asked if I’d smoked over 100 cigarettes in my lifetime (I hadn’t, but I thought about how other people answered this. Was this just something you knew? Or did people actually spend time counting their cigarettes consumed?). It asked if I’d ever removed mold from my home (I hadn’t), if there were any “traditional farm animals” on land where I lived or visited (there weren’t), and if I participated in any hobbies such as woodworking, welding, pottery, or “hobbies utilizing epoxy resin adhesives” (I didn’t). I knew these questions were meant to get a “whole picture” of the possible ways I could have been exposed to airborne toxins, but I wondered if they were just distracting me from thinking about burn pits. I wondered if the creators of the questionnaire knew that the people would automatically come to the questionnaire suspicious about burn pits, so they needed to shift their attention elsewhere.

The entire time I was completing the questionnaire my left lung — the one I’d had a CT scan on many years earlier — lightly ached and throbbed.

Even after claims about the dangers of burn pits started surfacing, the US Department of Defense continued to use them overseas. They claimed that incinerators were just too costly to operate, that there was no good alternative to burn pits. They claimed that open burn pits were the best way to reduce waste and protect service members.

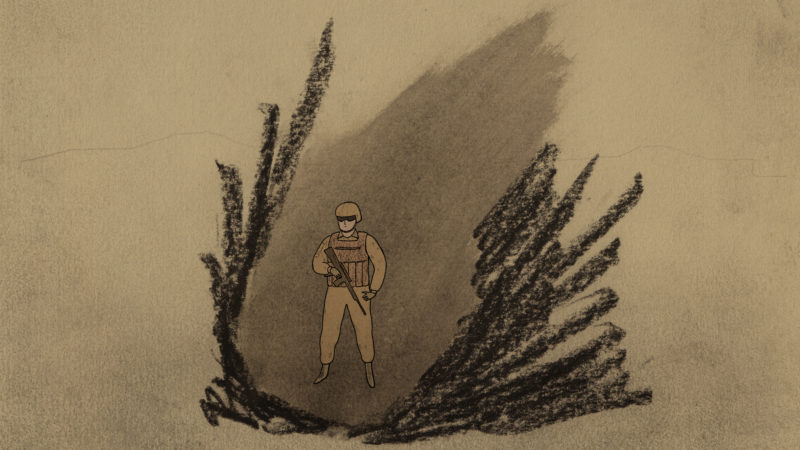

I don’t think about protection when I think about burn pits. I think about luck and ashy sand and falling into a deep, bottomless abyss. I think about uncertainty and the tree trunk scooped out by fire and all the different ways we catalogue and record how trauma can hollow out those it touches, like the Holocaust survivors and victims’ registries, and the registries created after the World Trade Center collapsed. Mostly, I think about how all the controversy around burn pits could have been avoided if there were more regulations in place about what could and could not be burned; if America’s troops weren’t thought of as expendable; if there were more sensitivity to how we damage the environment and how the environment can damage us back.

Sometimes, when I read about burn pits now, I catch myself holding my breath in anticipation. I’m not sure what I’m waiting for. Maybe for the research to speed up or to produce some missing piece of information explicitly linking burn pit exposure to specific illnesses and conditions, or maybe for some magic remedy to ease the anxiety associated with waiting to get sick. Really, I just want more accountability. I want the military to more explicitly acknowledge the mishandling of burn pits that killed and harmed so many people, both military and civilian. I don’t expect to get this anytime soon, so while I wait, I’ll keep reading about burn pits and sharing stories of veterans getting sick and holding my breath, waiting for the day to let all that air out.

The final part of my appointment is a breathing test to measure my lung function. I am told to take a deep breath in and then exhale as hard as I can into the spirometer, which is connected to Maddy’s computer. Maddy pretends to put the spirometer into her mouth and demonstrates what I should do before handing it over to me.

I put a nose clip in place and insert the spirometer into my mouth. I sit back in my chair, my back stiff and as upright as I possibly can. Then I nod at Maddy, take a deep breath in through my mouth, and push that air out as fast and as hard as I can.

“Keep going, keep going, almost there,” Maddy says, watching the program on her computer record my breathing.

I wait for Maddy to give me the all clear, then remove the spirometer from my mouth and the clip from my nose and cough into my sleeve.

“How was that?” Maddy asks.

I sit back in my chair and look over at her.

“Fine,” I say. “Just fine.”

I can’t tell if Maddy thinks my breathing is normal or if she already detects something is wrong with me based on comparing my data to that of other vets she’s interviewed. I want to ask her about all the others. I don’t talk to the men and women I served with anymore and now I’m finding that I wish I had stayed in touch with them, so I could ask if anyone else was feeling this anxiety about burn pits, if anyone else couldn’t stop thinking about them. But I don’t. I just smile at Maddy when she tells me to take a minute to compose myself before I breathe into the spirometer again.

I do the breathing test three more times, coughing into my sleeve after each test. Then, Maddy takes the spirometer and inserts a canister of albuterol, which is supposed to open up my airways. I take two puffs of albuterol, and after 30 minutes, we perform the breathing test again. I don’t feel a difference as I push the air out of my lungs.

I will receive the results of the breathing test a few weeks later, in the form of a letter from one of the researchers. My breathing is normal, nothing to worry about and no better after using albuterol. I’ll stare at the letter for a few minutes, wondering how useful this new information is, how truthful it really is, before filing it away with all the other stories and reports and research about burn pits.

At the end of the appointment, Maddy tells me about other studies being conducted on veterans’ health, and about an email listserv that sends updates about the SHADE study. I thank her as she walks me to my door, then shake her hand and step out into a hallway. I don’t talk to anyone as I walk to the main entrance. Instead, I keep my head down and slip out into the January sunshine, past the security guards manning the entrance, the wives looking for their wandering husbands, the vets in wheelchairs waiting for their rides. I escape back into the world undetected. Burn pits haven’t gotten me yet.