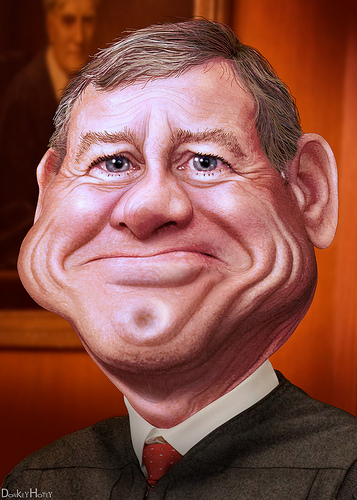

On Thursday, June 28, 2012, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts upended conventional wisdom, tripped up two major TV news networks (who initially bungled the story badly), and thwarted those trying to lay early odds on the Supreme Court’s treatment of the new federal health care law. Many commentators were baffled by the fact that the conservative Chief Justice joined the progressive wing of the Court to do a progressive thing: uphold what has come to be known in the press and popular discourse as “Obamacare.”

“If the Court guts these three classic clauses, Congress could be hamstrung in passing vital modern legislation. In the ACA decision, the Chief Justice started the gutting process.”

Part of why Roberts’ flip to the left seems to have caught us collectively off guard is that many in the chattering classes saw “Obamacare” (or its true name, the Patient Protection Affordable Care Act, or ACA) through the prism of executive power. In other words, this case (National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius) was framed as a clash between the Roberts Court and the Obama presidency. It wasn’t.

This was an easy mistake to make given that it is a Presidential election year. But Constitutional geeks knew all along that while the ACA case was fundamentally a fight between two branches of the federal government, it was a different pair: the case was really a face-off between the Judiciary and Congress. (If you do want to see a true clash over executive power, check out the unanimous Supreme Court decision ordering President Nixon to turn over his incriminating White House tapes during the Watergate scandal.)

Litigation over Obamacare had little to do with Article II (Presidential) power, and everything to do with Article I (Congressional) power. Whether or not Obamacare was Obama’s policy baby, the Constitution vests Congress with the authority to craft new legislation. Our Founders, who were suspicious of concentrating too much power in too few hands, broke up power: both vertically among the states and federal government and horizontally across the three federal branches. One of the things the Founders denied the Congress was a straightforward police power. This has left one hundred twelve Congresses with a conundrum: namely, how to enact needed federal laws if there isn’t a clear enumerated power in the Constitution.

The Congress has traditionally fallen back on a few key textual hooks in the Constitution as sources of its legislative powers: (1) the Commerce Clause, which allows Congress to regulate interstate, tribal and foreign commerce (2) the Spending Clause, which allows the Congress to spend for the common defense and general welfare, and (3) the Necessary and Proper Clause (a.k.a. the Elastic Clause), which allows Congress to make laws that are necessary to carry out its enumerated powers and the Constitutional powers vested in the U.S. government. If the Court guts these three classic clauses, Congress could be hamstrung in passing vital modern legislation. In the ACA decision, the Chief Justice started the gutting process.

“While seeming to go left, Roberts really went far right.”

The press has gone gaga over Justice Roberts’ apparent flip from the conservative side to the progressive side. (Reports are flowing in that Roberts was originally going to join conservatives to knock out the whole health care law, but at some point this spring, he changed his mind and decided to uphold the majority of the law.) Closer inspection of the actual written opinion shows Roberts gave those who want to hem in Congress’s power everything they wanted except ACA’s head mounted to the wall. He denied them that trophy, but he provided the blueprint for a radical rebalancing of powers among the three branches.

First, Roberts held (as the four conservative Justices did as well) that ACA’s individual mandate was beyond Congress’ Commerce Clause power. The Commerce Clause jurisprudence has been a mess since the 1990s, when the Rehnquist Court started stepping on the legislature’s toes, by changing the reading of the Commerce Clause from a nearly absolute Congressional power to one curtailed by states’ rights. Now we have garbled case law saying that Congress can regulate racial discrimination through the Commerce Clause, but not certain aspects of gender discrimination. And that Congress can regulate tiny amounts of wheat through the Commerce Clause, but not guns in schools. Confused? It’s not you; it’s the Court.

The ACA decision shows that five Justices think that regulating the health insurance market is somehow outside of the powers granted to Congress by the Commerce Clause. This is remarkable and bodes poorly for the next time Congress wants to rely on the Commerce Clause as its Constitutional source of authority.

The case raises an important question, one that now hangs like the Sword of Damocles: for these five men, what else is outside of the Commerce Clause power? Is banning racial discrimination in restaurants through the Commerce Clause now up for grabs? Is the federal late-term abortion ban now Constitutionally unsound? Remember, that was done through the Commerce Clause too.

“For Americans who get to keep their ill 25-year-old son on their insurance, or a cancer patient who finally gets coverage, the Supreme Court’s convoluted logic doesn’t matter, and certainly doesn’t invite scrutiny.”

Second, the Spending Power has long been one of Congress’s ways of getting states to do what it cannot do directly. Think of this as the Congressional version of “you can have your allowance, but only if you clean your room.” Only here, the messy-roomed children are the 50 states and the allowance is millions of federal dollars. The Congress can give states money for various federal programs in exchange for a state’s participation in the rules of the federal program. States are free to say no to the federal program and the federal money. If the states say yes, then the Congress can place conditions on the money it gives to the states, so long as the law is not coercive for states.

The last time the Court looked at the Spending Clause, it concluded Congress could withhold a percentage of federal highway funds in exchange for imposing a drinking age of 21. In the entire history of the country, the Supreme Court had never ruled Spending Clause conditions to be coercive. That was until the ACA decision. Roberts stated that ACA’s Medicaid expansion was “a gun to the head” for states and Congress had exceeded its powers under the Spending Clause. For the first time in history, the Supreme Court has found an outer limit to Congressional Spending powers.

In practical terms, this means Congress can’t cancel a state’s Medicaid dollars if it refuses to participate in ACA’s Medicaid expansion. This removes a major incentive structure for all states to join the new system. Florida’s Governor has already said Florida won’t participate in the Medicaid expansion. This could be devastating for Florida’s working poor if they get caught in the cross hairs between federal rules and the state’s intransigence. A big Constitutional issue for the next decade is likely to be what else is out of bounds under the Spending Clause.

Finally, the government argued that if the ACA’s individual mandate could not be sustained as an exercise of the Commerce Power, then it could be upheld under the Elastic Clause as being both necessary and proper. The basic argument was the individual mandate was necessary to solve the free rider problem of healthy people waiting to buy insurance until they are sick. Here too, Roberts dug in his heels and said, “no.” He wrote that he could not find Congressional power to require individuals to buy health insurance in the Elastic Clause.

Typically, the Court has expanded Congress’s enumerated powers through the Elastic Clause, and there’s a textual reason for this. The language in the Constitution is: “Congress shall have the power” to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers , and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States…” Importantly, there is an “And” right before the Elastic Clause indicating that it is an additional Congressional power. Yet in Roberts’ deft hands, the Elastic Clause has snapped back; curtailing instead of expanding Congress’s power.

As an alternative to going the more obvious route of giving Congress the authority to legislate in the health care arena through one of the three classic clauses, Roberts performed a textually suspect high-wire act where he found that what Congress had repeatedly called a “penalty” was actually a “tax,” but that it was a “tax” only for Constitutional purposes and not for statutory purposes of the Anti-Injunction Act. Don’t try this type of analysis at home, kids. But by declaring the individual mandate simultaneously a “tax” and “not a tax,” he saved ACA from dying in the hands of the Court.

But herein lies the true genius of the John Roberts head fake. While seeming to go left, he really went far right. The health care law was upheld, so he is lionized on the left. For Americans who get to keep their ill 25-year-old son on their insurance, or a cancer patient who finally gets coverage, the Supreme Court’s convoluted logic doesn’t matter, and certainly doesn’t invite scrutiny. Had the Chief Justice also invalidated the health care law while neutering Congress, the press would have taken far greater notice of the damage this decision has done to the balance of powers.

Deep inside the Congressional office buildings, there should be a collective chill shooting down every policy staffer’s spine because the ACA decision placed huge legal stumbling blocks in front of future federal legislation—some of which may prove insurmountable. All the language in the case about Congress not being able to make Americans eat broccoli sounds oddly peevish now. Those words will sound devastating if they are used as weapons to gut our food safety regulations, environmental laws, our civil rights acts or our voting protections.