Images courtesy of the author.

At the beginning of March I found myself watching the local South Bend, Indiana news in the waiting room of an obstetrics and gynecology practice. The TV reporters were covering the death of a former Notre Dame University President, Father Theodore “Ted” Hesburgh. He was ninety-seven years old when he died, and had been President of the Roman Catholic institution for thirty-five years. Notre Dame’s president, Rev. John I. Jenkins, said in a statement:

“In his historic service to the nation, the church, and the world, [Hesburgh] was a steadfast champion for human rights, the cause of peace, and care for the poor.”

Before the story was over I was called in to see Dr. Kelly McGuire. I wasn’t there because I was sick or pregnant: I was there to talk to McGuire about what happened when thirty-three-year-old Purvi Patel was admitted to St Joseph’s Regional Medical Center around 9:30 p.m. under McGuire’s care.

The middle-aged former Marine walked quickly through the halls of his clinic before leading me through the door to a small office, empty except for a desk and two chairs. McGuire confessed that his hospital had asked him not to speak with the press about Patel’s case, “but,” he said, “I don’t want [the hospital] talking for me.” McGuire barely moved and kept his gaze on the wall during our interview, which was originally used in a story for PRI’s The World.

He told me that on the night of July 13th, 2013, he was at home when he got a text message from his partner, Dr. Tracy Byrne, who wanted a second opinion about “something unusual.”

McGuire feared Patel had experienced a live birth and that her baby might be somewhere in desperate need of medical care.

Byrne was referring to Purvi Patel. She was bleeding from her vagina, and told her doctors that she had experienced a miscarriage around eight weeks into her pregnancy. After examining Patel, McGuire came to a different conclusion: “She did indeed have an umbilical cord that looked like it was from a baby that was fairly far along,” McGuire said. He feared Patel had experienced a live birth and that her baby might be somewhere in desperate need of medical care.

As a physician, McGuire is a mandated reporter of child abuse. Because of his legal and ethical obligations, it’s unremarkable that he would call the police when Patel’s account conflicted with his medical opinion. It is unusual, though, that before calling the police, McGuire looked up Patel’s address and phone number. He relayed this information to the police, explaining that he was afraid that Patel had given birth: “I thought that they should go out to her house and look for this baby.” he said.

When McGuire and Byrne told Patel that police were on their way to her house, she revealed to them that she had delivered a fetus, but it was dead so she put it in a plastic bag and dropped it in a nearby dumpster on the way to the hospital. Patel’s decision to leave the fetus there was a major focus in early news reports and at trial.

McGuire left Patel’s care to his partner. After informing law enforcement of this new development, he walked over to the fourth-floor windows where he watched the police-car lights racing through the dark.

“It was kind of surreal, kind of like something out of a movie. You don’t hear the sound but you just see the movement with the lights and it was dark. I could see multiple police cars coming from different directions.”

McGuire, a member of a pro-life OBGYN group, says he felt like it was a “search effort” at this point. He wanted to be helpful in some way so he got in his car and headed to the dumpsters where he had directed the police. When he got there, the cops let him help search for Patel’s fetus, and when they found it, they gave the doctor some gloves and allowed him to examine the fetus: “He was clearly dead,” McGuire said.

McGuire would later testify that he believed the fetus to be about thirty weeks gestation—about seven months—based on his assessment of the remains in that dark parking lot. His estimation would be the highest gestational age among the doctors who testified.

Patel, the grown daughter of immigrant parents, is not talking to the press, but Sue Ellen Braunlin, an advocate from the Indiana Religious Coalition for Reproductive Justice, met me in her church’s basement youth room to describe what happened. She says Patel’s long day started at 1 p.m. when she left work at her family’s restaurant after having some pain she thought was sciatica. Patel spent the rest of the day in bed with a heating pad until about 7:30: “She got up to pee and went into the bathroom, and then it just all fell out is how she [described] it,” Braunlin told me.

Patel wanted to maintain her secret, and that’s why she put the fetus in a plastic bag and disposed of it away from her home before reaching the hospital.

Braunlin says Patel, still bleeding, tried to resuscitate the fetus—which was among the blood and fluid that gushed out of her—but was unsuccessful. At trial we learned that Patel lived with her conservative parents and grandparents, who were unaware of her pregnancy. Patel wanted to maintain her secret, and that’s why she put the fetus in a plastic bag and disposed of it away from her home before reaching the hospital.

After McGuire left the hospital to join the search effort, Patel was sedated for a procedure to remove her placenta, which, had it remained inside of her, could have caused fatal hemorrhaging. At 3 a.m., as she was waking from sedation, a police officer was directed to her room. He used an iPad to videotape an interview with the post-operative Patel. This video would later be shown during the trial despite defense arguments that it should have been thrown out since Patel was not read her Miranda rights.

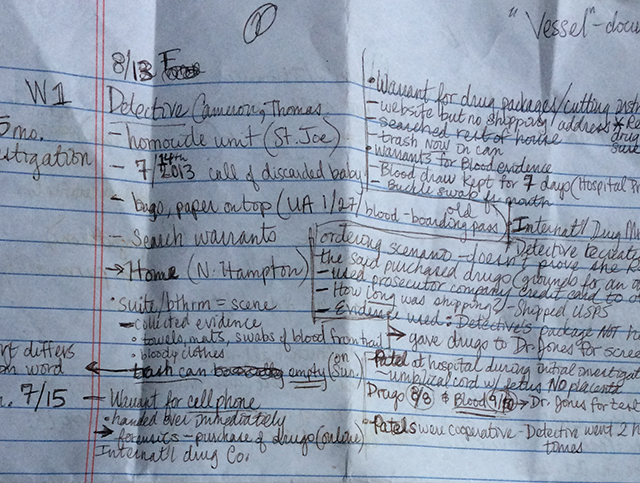

Emma Selm, also from IRCRJ, was at Patel’s trial the day that the video was shown. Her notes show the police officer telling Patel “You don’t have to talk to me, but you should talk to me. You’re not in trouble, but you really should talk to me.” Patel acquiesced to the officer’s demands, saying she just wanted to clear things up.

Selm said that the officer’s questions became strange. He wanted to be sure they found the underwear Patel was wearing when she lost her pregnancy, and at least twice he asked “What color were your panties?” He also asked about the father of the baby. Selm recalls, “she acted kind of embarrassed, like she didn’t want to talk about it.”

On the video, recorded right after Patel’s surgery, the police officer kept interrogating her: “Was it a one night stand or something? Oh and was he Indian too?”

Selm says the interrogator also asked about the friend Patel texted while being treated. “His follow up question was, ‘is that friend Indian too?’”

The entire video, which was over an hour, was played for the jury except for Patel’s address and birthday, which were obscured.

“But” says Selm, “they didn’t blur out what color her panties were.”

Purvi Patel’s case is troubling in many respects: The inconsistency of the simultaneous charges of child abuse and feticide show an unusual interpretation of the rule of law. While local right-to-life activist Shawn Sullivan has said he agrees with the verdict, even he finds the elements of the sentencing to be “somewhat contradictory.”

The pathologists who testified never reached consensus that the fetus was actually born alive.

Further, the feticide charge is based solely on text messages between Patel and a friend. When police searched her home they confiscated Patel’s phone and found messages that implied Patel had taken abortion drugs purchased online from Hong Kong. A toxicologist testified he found no drugs in her body and Patel’s preterm labor was never directly linked to these drugs.

In fact, the pathologists who testified never reached consensus that the fetus was actually born alive. One of the state’s pathologists who performed the autopsy used a discredited method called the “lung float test” to determine whether the fetus had taken a breath after birth. Patel’s defense tried to have this pathologist’s testimony thrown out, but Judge Elizabeth Hurley—appointed by conservative Governor Mike Pence—allowed it. Purvi Patel was sentenced to twenty years in prison for child neglect, a charge that depended entirely on evidence that the fetus was born alive.

Another important factor for the case was whether the fetus was old enough to live outside Patel’s body. The three pathologists who testified gave conflicting estimates of gestational age. The highest guess was twenty-seven weeks, still “extremely premature” by World Health Organization definition. Patel, believing she was only two months pregnant, hadn’t received prenatal care. Therefore she was never screened for conditions dangerous to a fetus like hypertension, diabetes, or infection. Coupling that with a delivery that didn’t include immediate respiratory support gave this extreme preemie almost no chance of survival. Respiratory distress is the biggest concern for neonatal providers since the lungs are the last major organ to mature.

The use of Indiana’s feticide law to convict a pregnant woman is unprecedented. The law, which has been on the books since 1979, was initially used to punish illegal abortion providers and reads:

“A person who knowingly or intentionally terminates a human pregnancy with an intention other than to produce a live birth or to remove a dead fetus commits feticide, a Class B felony. This section does not apply to an abortion performed in compliance with:

(1) IC 16-34; or

(2) IC 35-1-58.5 (before its repeal).”

Over the years feticide was added to statutes like murder and assault so that if someone hurts or kills a pregnant woman resulting in the death of her fetus, they would get additional time for that fetus’s death. Feticide was upgraded to a Class B felony in 2009 after a bank teller was shot and lost twins at five months gestation.

The most comprehensive review of cases of women being criminalized for outcomes of their own pregnancies shows women of color are far more often charged with these crimes than whites. Indiana’s use of the feticide law against pregnant women has been consistent with that aspect of the study’s findings.

Before Patel, the only woman charged with feticide in Indiana was Chinese immigrant Bei Bei Shuai, who took rat poison in a suicide attempt in 2010 while pregnant. Shuai lost her preterm daughter only a few days after delivering. She eventually pled guilty to lesser charges, but her case set a precedent: Judge Hurley cited Shuai’s case in response to Patel’s defense team when they argued against applying the law to a pregnant woman.

Reproductive rights advocates say charging pregnant women with harming their fetuses is part of a conservative plan to erode abortion rights across the country. The National Advocates for Pregnant Women say that though other women have been arrested and charged for terminating their own pregnancy or attempting to do so, this is the first time in US history that a woman has been convicted of feticide for attempting to end her own pregnancy.

Anything that threatens the trust in my relationships with my patients is potentially medically harmful.

As a nurse, my job has been to promote the health of women and their babies. The foundation of my work is the ability to build trust and to discuss some of life’s most intimate encounters. Anything that threatens the trust in my relationships with my patients is potentially medically harmful. Organizations like the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists agree.

One day, I started my shift at the hospital with discharge orders for a patient who was taking medication to slowly withdraw from her opiate addiction. She didn’t have a home to return to, so the social worker placed her at a shelter in the city center. As I wheeled her toward the elevator she grabbed my arm and said, “I can’t go there. I really can’t. Find anywhere else. I’ll even go out of town. I’ll stay in a psych unit. Whatever you have to do. My dealer is right around the corner from that place and if I go there I’m really scared I might go see him. Please, please help me.”

It was only because she was able to talk frankly about her addiction that we were able to place her somewhere safer for her and her fetus. But current fetal homicide laws threaten that relationship. Drug-addicted mothers have already been prosecuted under these laws in several states. If drug use during pregnancy continues to be considered criminal, healthcare providers may be required to have a role in law enforcement—in direct opposition to their role as caregivers. This could result in pregnant women avoiding treatment for fear of prison time. It’s unclear how far legislators will go to prosecute pregnant women in their efforts to “protect” fetuses. Cigarettes and alcohol are known to cause birth defects, low birth-weight, and premature deliveries. According to the Indiana Department of Health: “Over eighteen percent (18.5%) of pregnant women in Indiana smoke, nearly twice the national average (10.7%), making Indiana one of the highest among all US states.”; women in Indiana can’t afford to ignore the future ramifications of Patel’s case. Neither can local nursing or medical organizations. Phillip Morris’ parent company hasn’t yet responded to inquiries about the company’s stance on the use of fetal homicide laws against pregnant women for using tobacco. But alcohol and tobacco lobbyists may become powerful and strange bedfellows for medical providers if these laws continue to be applied to pregnant women.

In the meantime, all eyes are on Purvi Patel as her fate affects so many. Since her sentencing, Patel has asked to be provided with a public defender to help her appeal Judge Hurley’s sentence. National Advocates for Pregnant Women say they will assist Patel in her appeal either as co-counsel or by helping her find pro bono counsel and staying in an amicus role.