I found a photograph a few years ago. In the back of the kitchen drawer filled with stamps and batteries and all the tops of things that have lost their bottoms. In the picture it is sunny. I’m about eleven years old. I’m sitting outside and my high-water bellbottoms expose a sock-less ankle. My brown hair is collected in the loosest pony tail imaginable. My shirt is buttoned wrong and I’m in possession of an oddly folded piece of white paper. It’s sticking way out my breast pocket. A list? My Homework? I have no idea. I don’t remember anything about the day this picture was taken. But I know the location: the intersection of Washington Square North and 5th Avenue. I used to live around the corner.

I showed the photograph to my family. My eleven-year-old daughter was mesmerized by our resemblance. My facial expression, the baby like puff in my cheeks, the shape of my mouth, my hair—my features were hers. It was astonishing how much we looked alike. My husband was more taken by my chambray shirt. He wished I still had it. I sort of did too, even though I didn’t remember owning clothes like that, or recall being a child who was so disheveled. I was so haphazardly put together. I look feral. But the picture couldn’t lie, even if what it said about me was nothing I remembered.

My father died in May 1970. The rest of that spring I dreamt I was kicked out of my school. My teacher was always kind in the dream. I could tell he didn’t want to do what he was doing, but it was a rule. Night after night he explained how children without fathers were not welcome. I would have to leave. My mother went back to work the following fall, and I changed schools. A year later we moved from Park Avenue to Washington Square Park. I lost my childhood friends and my bearings. Time blurred and folded up on itself. I was eleven. I roamed the landscape of Greenwich Village after school by myself with a dollar bill and a house key. I remember 8th Street between 6th Avenue and University Place as a mirage of headshops and shoe stores. I fended for myself. Sometimes when I was feeling extra generous, I blew my wad on a pack of Drakes Funny Bones. The soft neon peanut butter filling inside was manna. A delicious gift. Nourishment. I was a latchkey kid. This was when I met John.

John had the biggest nose I’d ever seen. It was like a comic book version of an ugly nose. Huge, with a prerequisite wart on it.

John was something different for the latchkey kid. John fed you, for one thing, hotdogs, but still. John listened. John always took your side. John was loyal. He was patient. He was always interested. John was always there waiting on the corner with his hotdog cart. Stories circulated: he was a pedophile, a murderer, retarded, a convict, he paid boys cash to stay away from his corner. Some girls (all of John’s friends were girls my age), were forbidden to go near him. A mother generated a petition demanding his removal. I asked my mother not to sign it. John the hotdog man’s hot dog cart was opposite the arch at the entrance to Washington Square Park.

John had the biggest nose I’d ever seen. It was like a comic book version of an ugly nose. Huge, with a prerequisite wart on it. He looked exactly like Jimmy Durante. The way I saw it, he was way too ugly to be dangerous. And yet every afternoon he’d pick one of us up and set us on top of the warm cart for the rest of the afternoon. Like a hood ornament. We were all capable of jumping up there. Even me who was the shortest of the bunch, could easily climb up on it. He always had a plastic milk crate in front on the cart. But John liked doing it. His stubby fingers wedged themselves in our armpits so he could hike us up. I could feel the callouses on his hands, his fingernails sometimes, through my shirt as his hands lingered on my chest. I didn’t like when it was my turn. But he gave us hotdogs with whatever we wanted on them: onions, sour kraut, ketchup, mustard, the works. He never took our dollars. Why would we be scared?

I ate my dinner imagining John and his unwieldy cart careening through traffic somewhere. He’d have to return the unsold soda. Clean the mustard dispenser. It’d be hours before he got home. I had only ever thought of him on the corner, waiting for me.

I invited John for dinner once. My mother was furious. He requested beef stroganoff. She had never made beef stroganoff in her life and she said she certainly wasn’t going to make it for John the Hotdog Man. He brought flowers. He wore a jacket that didn’t fit and pants that were too short and too big. After dinner, which was beef stroganoff, he took me to the movies. To this day I don’t know why she let me go. She said it wasn’t safe. We argued for days. She said going on a date with him was inappropriate. But I was younger and stronger and I won. I said he was my friend. He was. She watched us get into the elevator. Our eyes locked as the doors closed. He and I walked slowly through the village to a movie theater that is now a health club. We saw Summer of ‘42. I had my own money but he paid and during a scene in a drugstore I whispered to John that I didn’t know what a condom was. He said that I should ask my mother. He returned me home safely at 10pm. My mother closed the door behind me and we never discussed the evening again.

Once I saw John break his cart down. I didn’t want him to see me. I hid behind the arch in Washington Square Park. I watched hot dog water dribble out of one of the compartments. I was embarrassed and his mustard stained apron looked especially grimy in the low light of dusk. He pushed the cart down the street like Sisyphus pushing a rock. He was short. He was a troll. It was sad. He was sad. He probably lived somewhere very far away. Like Queens. I went home a block away and did my homework. My room looked over Washington Square Park. I ate my dinner imagining John and his unwieldy cart careening through traffic somewhere. He’d have to return the unsold soda. Clean the mustard dispenser. It’d be hours before he got home. I had only ever thought of him on the corner, waiting for me. His life was awful.

Then one day he was gone. My mother said the police or the city or the mayor had gotten rid of him, removed him finally, from the proximity of so many school-aged children. He never came back to the corner. Was he a bad man? I had equal reasons to trust him and to be wary of him. I really didn’t like thinking about it. Eventually I stopped thinking about him.

It is a photograph of a girl crossing over to a place different from childhood. John the hotdog man isn’t in the picture, but his cart is, his presence is.

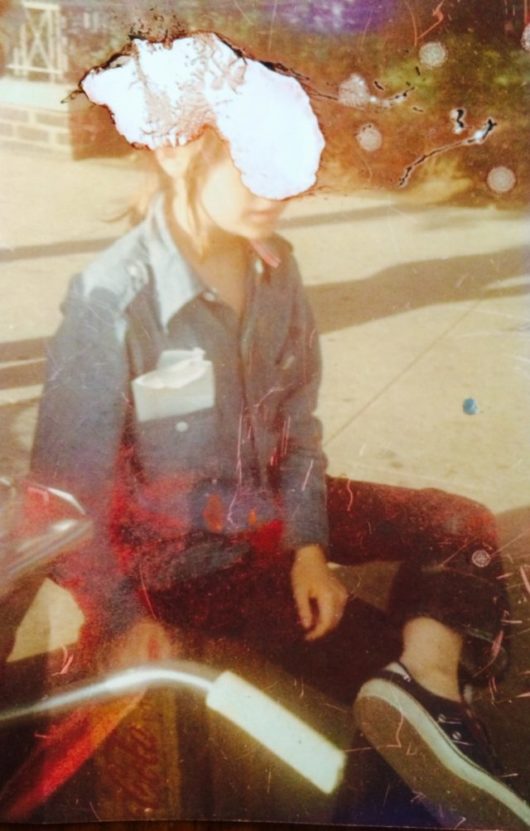

The picture of me in my bellbottoms and my ponytail made the rounds at dinner parties. I was obsessed with the image of the girl in that picture. The girl I didn’t remember who looked like the daughter I now had. I looked at it alone and in the company of others. Always turning it around and around as though looking at the picture from a different angle would reveal something I couldn’t see looking dead on. The picture lived on my mantle. A mysterious moment, frozen in time, it remained unframed. It was a conversation piece. A faded souvenir of the 1970s in Kodak Kodachrome. Then one day I saw what was clearly the handle of John’s cart. Right there in the lower left hand corner. The chrome gleamed. This is a picture of me sitting on the milk crate next to John’s cart. John probably took the picture one afternoon, after school, one block away from the apartment I shared with my mother a year or two after my father died. It is a photograph of a girl crossing over to a place different from childhood. John the Hotdog Man isn’t in the picture, but his cart is, his presence is. I put the picture back on the mantle. But I stopped showing it to people.

Yesterday a fine mist of vinegar, and whatever else is in Windex these days, landed on the picture that I never got around to framing. I stood with a rag in one hand and cleaning spray in the other watching my own image literally disappear. A chemical chain re-action occurred and white light replaced my nose, my eyes, my forehead. My features went up in a flare. Most of my hair bled out. I was seized by panic. All the information I‘d hoped to glean from the picture was vanishing. Just like the memory had disappeared before I found the picture. The only thing left behind was the hot dog cart and the white handle.

I was hysterical. What was wrong with me? Why didn’t I frame it? Why don’t I ever pay attention? I’m careless. I’m an idiot. No, I told myself. It’s okay. It’s okay. It’s okay. I said it over and over like a mother tells a child. It’s okay. Shh. It’s okay. Because it is. I’m still here. In the flesh. Even if I disappeared for a decade or four. I came back.