Vikram Chandra’s Sacred Games is a 900-page novel woven around the confrontation between a police detective and a gangster. It spoke to me in a voice and dialect I am intimately familiar with, that of my hometown Bombay. As a naturalized American, the struggle to belong here while holding on to my Indian roots has always made me seek out desi authors. They are, some deep conviction tells me, the means to understanding myself better. I decided I had to be friends with Vikram. I didn’t have to look very far to find his email. It was printed right on the back jacket of the novel—a habit retained from his computer coding days.

Perhaps we become friends because we’re both from South Bombay and now live in America. Or perhaps because he was nice to my mother, who accompanied me to our first lunch. She isn’t much of a reader, so, despite my constant quoting from Sacred Games, Vikram steered the conversation away from literature. Or perhaps we became friends when, in grad school, I introduced him at a reading.

Or perhaps when we shared a forty-five minute cab ride in Manhattan. We disembarked in a gated courtyard stained by a patch of grass, peppered with flowers. The perpetual roar of New York’s surging traffic–vehicular and pedestrian–was missing in there. We were surrounded by tall buildings that were painted a stark white. I felt grateful for my sunglasses. We were there to look up a woman Vikram used to code for during his film school days at Columbia. Over the years, he tried contacting her many times.

After a decade in New York, the incessant sunshine, greenery, clean air, driving, smiles and eye contact, all of it smothered and oppressed me.

The doorman said she’d moved out many years ago. He had no idea how to get in touch with her. “Just in case,” said Vikram, handing him a piece of paper with his phone number. When the doorman looked quizzical, Vikram explained, “She was a friend.”

I was not a good friend to Vikram. He lives in Oakland, a ten-minute drive from the UC Berkeley campus, where he teaches literature and creative writing. I recently returned to the Bay Area, where I’d spent my undergraduate years. After a decade in New York, the incessant sunshine, greenery, clean air, driving, smiles and eye contact, all of it smothered and oppressed me. I emailed Vikram that I was back and he invited me over for the release party of his latest book, Geek Sublime: The Code of Beauty, The Beauty of Code, a finalist for the National Book Critic’s Circle Award. I had an impression of the book as a computer-techy sort of thing, a subject I find cardinally boring. Also, it was non-fiction. Anyway, I resolved to read it before the party.

And then I didn’t do it. I got busy with my job, and with my own writing, and procrastinated. So it was with much trepidation that I parked my mother’s old car, a 2001 Honda—her first after we had immigrated to the US from India—and got out on Vikram’s street.

The trees that lined the block afforded me a shady green canopy to walk under. Their perfect symmetry—a Californian landscaping quality I find exceedingly irritating—was quickly mitigated by the unique designs of the houses beyond. A red brick one here. A pista green one there. Two stories, a brown roof, white trim. One story, a black roof, and a red chimney. No house a replica of the other.

Vikram’s house is steel grey and has dark wood shingle sidings. I climbed up the stairs and paused on the porch. There was the murmur of conversation, an excited hoot, laughter, and the high voices of children. I rang the bell.

In jeans and his signature button-down linen shirt, Vikram opened the door. He smiled and said, “D.” I felt the same rush as when he’d first started addressing me that way in his emails. It’s what my friends back in Bombay call me, too.

Initially, I’d wondered why he’d adopted that particular nickname. Then, as I got to know him, I understood. What made Vikram a great novelist was his tremendous sense of people. This served him well in Bombay, as he shadowed both police and gangsters, harvesting stories for Sacred Games. People find him affable, they feel terribly comfortable with him, so they half-share pieces of themselves. Vikram adds those pieces to his observations—a police detective’s penchant for nice shoes, gossipy rivalries among Bombay’s elite circles, “D.” instead of the trisyllabic name that means “sun” in Sanskrit. Then, he spins everything into his fiction.

“Come in,” said Vikram, opening the door wider and smiling. He’d lost weight since I saw him last, which, I found out later, was owing to regular exercise on an elliptical machine beside his writing station—a three-monitor computer.

The fact that I was still lingering outside would have made anyone else say something, but Vikram patiently waited. I blurted out, “I’m sorry I haven’t read the book yet!” Then, I stepped back, anticipating the inevitable blow of his disappointment.

I have since read Geek Sublime. It is Vikram’s fourth book, after Red Earth and Pouring Rain, Love and Longing in Bombay, and Sacred Games.

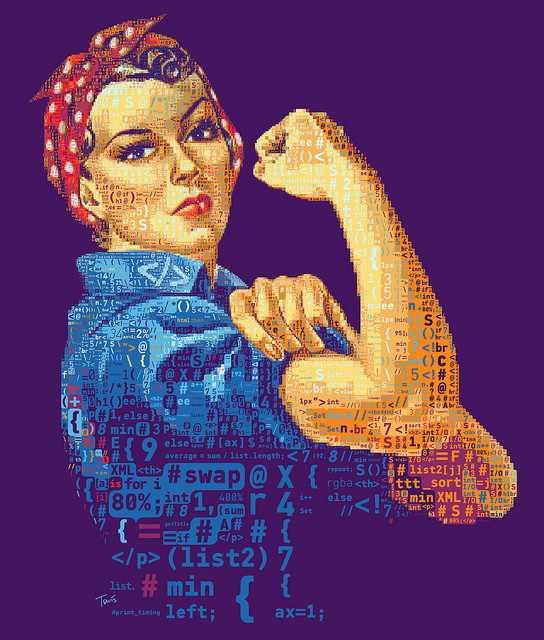

Like Vikram’s fiction, which weaves the seemingly unrelated into a unified, single world, Geek Sublime, his first endeavor in non-fiction, begins with computers—the machines and their coding languages—and then seamlessly journeys through the writing process, programming culture, feminism, colonialism in India, and the Sanskrit language, before climaxing with Indian aesthetic and dramatic theories.

The range of disparate things sewn together is incredible. He leaps, for instance, from Sanskrit to modern linguistic theory to computer coding languages. We begin with a text known as the Ashtadhyayi. From 500 BCE and credited to Panini, an Indian grammarian, the Ashtadhyayi is written in and is about the Sanskrit language. Listed in it are 3,976 Paninian rules that encompass any and all Sanskrit words. The way these rules classify and break down Sanskrit shaped much of modern linguistic theory, which, in turn, influenced the governing principles that programmers use to formulate their own computer languages viz. FORTRAN, or the Backus-Naur Form.

Rasa literally means “taste” or “juice,” but in this context it is the aestheticized satisfaction of “tasting” artificially induced emotions.

The discussion on computer languages then moves to a discussion of beauty. In the programming world, your code is judged for its functionality and efficiency, sure, but also for its elegance. And from that observation we enter my favorite part of the book. In 200 BCE an Indian sage named Bharata is said to have written the Natyashastra (Treatise on the Drama), a theater professional’s handbook. Its first five chapters concern what the playhouse should look like, costumes, make up—all the physical elements of a dramatic performance. The sixth and seventh, however, analyze the nature of aesthetic pleasure, or rasa.

rasa literally means “taste” or “juice,” but in this context it is the aestheticized satisfaction of “tasting” artificially induced emotions, or, as Vikram explained it to me when I asked, “It is the feeling of satisfaction you get after having enjoyed a delicious meal. It is not the meal, nor the process of eating, but afterward. When you’re full and satisfied and can look back upon the meal with disinterested pleasure.”

I have encountered this idea of disengagement before. Buddhism promotes detachment from the earth as way to attain Nirvana. St. Ignatius of Loyola counseled detachment. The Philokalia endorse it as a means to a spiritual life. “Disengage disengage” is a mantra in the Dune books (like Vikram, I love science fiction). However, on that stage framed by Vikram’s porch, I was incapable of it. There is nothing elegant about waiting for the blow of your mentor’s disappointment.

“Relax, D,” said Vikram. And, just like that, I did.

I was reminded of an author who interviewed him at Kepler’s Books in Menlo Park once. Vikram, who doesn’t drive, hitched a ride with me. I told this interviewer later that with New Yorkers you always knew where you stood. “Californians,” I scoffed. “Are only nice to your face.”

“Think of a duck,” he said, with an infuriating smile. “Serene on the water’s surface, but underneath…” He stretched out his hands and flapped them furiously up and down. “Struggling to stay afloat.”

My impression of Vikram has always been that he is a very laid-back person. He is, if you speak Hindi, supremely bindaas. When I said this to him, he laughed and said he was just better at keeping it under wraps, is all.

Spared from the tidal disappointment I’d expected, I stepped forward to meet Vikram’s wife, Melanie Abrams. She is also a writer and also teaches creative writing at Cal. When I told her I adored her husband, she said, “You mustn’t know him that well.”

We laughed, but mine was a bit stilted. I wondered at my own ability to see Vikram—whose work has been so instrumental in forging my own voice, whose mentorship is rendering California bearable to me—objectively.

“I’m sorry but I have not had the chance to read…” I began apologizing to her, too. She changed the subject. My inner flagellant at rest, I moseyed out to the yard, where the party was humming. The crowd was diverse and mostly academic. There were drinks and appetizers. And there was a white cake, angel food, and moist, with a layer of custard icing in the middle. The icing on top was a photo print of the book cover. On the radio that day, everyone was going on about David Beckham’s latest tattoo, of a Jay-Z lyric: “Dream Big Be Unrealistic.” It’s on Mr. Beckham’s right hand. Myself, I’d have gotten 50 Cent’s “I love you like a fat kid loves cake.” The affair with cake is why I can’t shake the ten pounds I resolve to lose every New Year. I snagged two generous-sized pieces.

“Hello,” said a white man dressed in a beige Indian outfit—tight cotton pants, a long sleeve cotton shirt, and a silk jacket with a Nehru collar and no sleeves.

I nodded and choked out a “hello” through the last bite of my third piece. He was the best-dressed person at the party and I said so. He thanked me and slightly bowed. “I haven’t read the book yet,” I said, defensively, and asked if he’d read the Ramayana or the Mahabharata. He’d read both; I’d read neither. “I love the epic tragedy of the Mahabharata more than the sterile morality of the Ramayana,” I said, extrapolating from my memories of some television shows based on the two texts. (Later, I found out the shows are very close to the original sources, thank God.) Avoiding his eyes, I looked at Vikram’s girls, Leela and Darshana, playing on a slide. He spoke, and made what I said sound intelligent. Now I was terrified he’d figure out my source. I quickly interjected: “So, what do you do?”

“I teach Sanskrit,” he said.

“Cool,” I said. “But can you speak it?”

“Sure,” he said, and obliged.

“That,” I said, “is really …”

“Something,” he said, helpfully, a twinkle in his blue eyes.

“So,” I said. “How do you know Vikram?” I wasn’t surprised: he was also a professor at Cal. Later, Google would afford me fresh horror. He was Robert Goldman, the principal translator of a massive, fully annotated translation of the Valmiki Ramayana.

When Bob and I cordially parted ways, I was struck by the feeling that I had failed, that I was a fake. A foreigner knew more about my birth country. Of course, I’d been a US citizen for years and had left India over a decade before. But still.

Needing an upper, I made my way into the house, where food was being served. More importantly, where they’d moved the cake. There I met a literary agent who had recently come to San Francisco from New York. She was Indian, and our exchange over another slice of cake—I really didn’t have the guts to commit to a full fourth piece, so we shared it—made me feel like an even bigger phony.

When I reached and reached within myself for things about our former country to share so we could bond, everything seemed lacking.

She, a Christian raised in a largely Hindu country, like me, also knew more about the Mahabharata or the Ramayana than I did. She’d traveled far more extensively through India than me. She’d lived in Bombay, too, though not for long. When I reached and reached within myself for things about our former country to share so we could bond, everything seemed lacking. I was enveloped by a general malaise. But I still couldn’t put my finger on what my problem was, exactly. I knew this much: cake was not helping.

And so India was on very much my mind as, later, I began imbibing Geek Sublime. I say “imbibe” because when I arrived at Vikram’s discussion of rasa, that pleasure attained by looking upon a meal after having imbibed of it to your satisfaction, I saw the solution my previously unidentifiable problem. It was not, as I’d thought, a general malaise.

I had been naïve. And blind stupid about rasa. Vikram had said, “…look back upon the meal with disinterested pleasure.” Disengagement was only one aspect of rasa. Disengagement without pleasure could just as well be a response to a traumatic experience. What the Dune characters consciously practiced, what various religious traditions teach, what I did to avoid the blow of Vikram’s disappointment. I had disengaged and therefore relaxed, but had I experienced any pleasure?

rasa cannot be experienced by the naïve viewer who construes what’s occurring in the drama on stage, or film, or in any media, as reality. The connoisseur is able to experience rasa precisely because he or she does not identify personally with the fictional matter at hand. A psychic distance from the drama is necessary for rasa since it is an impersonal, disinterested pleasure. In this way, rasa has transcendence. Or, as Vikram aptly puts it, “Rasa is sublime.”

This idea of impersonal engagement as being more desirable for the experience of pleasure is also explored by Roland Barthes in The Pleasure of the Text. Barthes raises the French vocabularies of pleasure that we lack in the English language, jouissance and jouir, and examines a simple question: what do we enjoy in the text?

Barthes is concerned with the pleasure we take in our reading, as opposed to some indifferent process of knowledge acquisition. For him, our pleasure is individual, specific to us in the corporeality of our bodies and everything that entails, but not personal. Our pleasure is removed from us. Whenever Barthes analyzes a text that has given him pleasure it isn’t his subjectivity, personal to the text at hand, that he encounters, but his impersonal individuality. His historical subject of self attained at the conclusion of a very complex process of biographical, historical, sociological, and neurological elements (education, social class, childhood configuration etc.).

And so my hunt for the pleasure, for true rasa, led me to explore my own individuality. I began to wade through my various selves. They jumped out of the water and paraded before me. As they dried off in the sun, I ticked them off my list.

There was my naturalized American self. My Indian self. My Catholic-in-a-largely-Hindu-country self. My New York self. My California self. My writer self. My acolyte-of-Vikram self. All these selves and their many languages. As I attempted to impersonally evaluate these and others with other languages, another idea came to me. Now was also my chance to examine Vikram objectively.

But, I see Vikram telling me to “relax.” Suddenly I am disinterested. I see myself from the outside. I am an amalgamation of many pieces, of many places, of many times.

Retrospectively, I observe myself at Vikram’s party. I grab my fifth piece of cake—it is large enough to make up for that missed half of the fourth—and walk into the emerald light of the backyard. Leela and Darshana wave to me before resuming their play. Melanie and Vikram pull me into a circle with all their friends.

We talk about many things, including, but not exclusively, India, and as that custard-like icing melts in my mouth I stand beside my bindas and brilliant author, my mentor and fellow-Bombayite-in-America, my friend. As I listen and occasionally contribute, I begin to experience the disengaged pleasure, the subliminal rasa. But because of something personal in there too, something beautiful and elegant, something to do with my identity, and with the insight into my language Vikram gave me with Geek Sublime, it isn’t totally disengaged.