With Nathaniel I lived in a beautiful home. I intensified its beauty by bringing nothing with me. Nathaniel would have been horrified to see what my previous home looked like, which was one reason I never let him see it. But I will tell you: I had become a victim of detritus. These things weren’t exactly garbage, which was much more challenging than if they had been. They were coin purses and candles and novelty cutting boards with cocktail recipes engraved in them. Live batteries separated into pairs in ziploc bags. Rolls of movie posters, eons of stylish favorites, gummed up in the corners with filthy tape residue. Nice liquors and cheap ones. Clothes I hadn’t worn in several years. Clothes that didn’t fit anymore. Soccer cleats—an entire soccer uniform. The oldest things in the collection reached back into adolescence. I heaved everywhere with me a Chekhov’s gun collection: things that, because I had kept them around, promised to become relevant again at some point.

This was the philosophy, and the menagerie, I abandoned when I moved into Nathaniel’s clean, all-white, one-bedroom apartment, and instantly I felt lighter. He had almost no belongings. His bed—ours—was only a mattress that lay on the floor of the bedroom, in its corner. There was a desk in one corner of the living room, and, catty-corner, a blue futon. Light came through the uncurtained windows and poured onto nothing but the hardwood floor. Coastal pine, very light. Suggesting beach sand but plasticky smooth. There was a very slight echo in the apartment when Nathaniel or I spoke, like our speech stood in bas-relief, an effect especially pronounced when we made love, which we did plenty. His being so much taller meant he could hold me up levered against the wall, which a man had never done to me before. I liked it very much. We spent a lot of time doing this.

We ate only plants. Nathaniel had been living this way for some time, but it was new to me. My first struggle as a homemaker was with which plants went in the refrigerator and which sat out. Celery in, lettuce in. Spinach in. Baby spinach in. Bok choy, brussels sprouts, mung beans, collards, asparagus in. Tomatoes out, cherry tomatoes in. Onions in, shallots in, scallions out—in water. Cobs of corn out, unshucked. Garlic in, in a drawer. Bananas out, avocados out, oranges and tangerines out, squash and eggplant out. Apples in, plums and peaches out. Potatoes in bulk sacks. Unsalted nuts in vats for scooping out handfuls when in need of energy. Nathaniel said the plants went bad faster when they sat close to each other, so I placed all the vegetables of the house in their own personal spaces. The kitchen, white, seemed to sprout them all over. This led to my second struggle as a homemaker: odd plants, spread too thin, or hiding, could be forgotten until their stink announced them.

My third struggle was with my stools. Forgive me. But they were loose. Every morning I spent an hour in the bathroom. Nathaniel said his movements were effortless. It seemed like a lie; I knew how much fiber we both ate. But our home together was too small for him to conceal a struggle. He went into the bathroom and two minutes later he came out, lighter and lighter still.

Among my detritus I had lost my job, so Nathaniel got me a new job. It was related to his job. He was a software engineer for an online dating company, and there was a small but crucial job there that needed constant doing and could be done from home: investigating flagged communications. The gist was that people wrote to each other on the site to make romantic connections, and not uncommonly they would report each other’s writings as inappropriate, for two main reasons: spam and obscenity.

At first, I read them. Spam was the bigger problem. A lot of the site was made up of robots sending gibberish to people, or garbled advertisements, or naked links to ugly, harmful places. There were so many robots using the site that I imagined sometimes they would contact each other and happily speak nonsense to each other’s stolen avatars. But of course I could never see those exchanges: there was nobody to flag them in objection.

As for the smaller and more grotesque problem of human offenses, I did my job so robotically that a piece of engineered software surely could have done it. I banned every flagged user. Some of these cases might, by the flagged party, be considered ones where nuance and sympathy were exactly the reasons to have a human review service for flagged posts. The line between pursuit and harassment—come-on and indecency—was a vast and murky span that only I could interpret fairly. The only fair arbiter, though, was a consistent one—plus I got paid by the completed ticket, and the supply was inexhaustible. Plus I looked into the grins and moues—these people’s most flattering angles—and began to feel righteous and retributive when I did it. Plus the motion of pressing on my trackpad became as close to automatic as I could make it without removing myself. I was free to do anything I liked with my day, so long as I remained at the computer with one finger tapping. Normally, I watched films: shrunk and resized onto one half of the computer screen, while outrages passed through the other.

I learned of Nathaniel that he had never had a pet so I found two kittens for us, from a litter a man was selling in a cardboard box down on the street. One was orange and one was calico. Nathaniel named them Gustav and Emilie, after Klimt and his companion.

It was nice to have them around. Especially during the day, when Nathaniel went to work and I was alone. I tapped my trackpad serenely and watched small skittering movements across the floor, heard small sounds. They crawled all over the apartment. There wasn’t anything for them to play with so I tore off sheets of tinfoil and made balls for them to chase. They really liked that.

With the cats in it, the apartment became a little filthier. Mainly it was the litter they tracked around. It blended perfectly into the light pine floors like grains of beach sand. Granules stuck to my feet and fell off in our bed when I got in. There was, after a while, a certain amount of litter in the bed. I was scared that the cats would misinterpret the bed as a second bathroom for them but they never did. They had strong instincts to use their box, which never smelled. I cleaned it every day.

When they grew big enough and I took them to be spayed and neutered, the doctor said it was already too late: Emilie was pregnant. She curled and struggled on the table while the doctor told me this. In two months, the doctor said, she would have kittens, and I probably would not need to do anything to help, but I ought to keep a vigilant eye on her and the pregnancy. I left Gustav with the doctor for the night—he could still be taken care of—and rode back to the apartment in a cab with Emilie.

Her small gray cage shook in my lap as she rearranged herself again and again with the car’s movements. I peered through the grate and wondered if there were, in her small, alert face, an indictment: right under my nose, this had gone on, me staying home every day with them. Right under my nose the passage of four months with Nathaniel in my new home, where nothing accreted to mark the time.

I did Nathaniel’s laundry for him. Try hard not to take that the wrong way. He didn’t ask me to, but I spent all day without him, among so few of his things. One thing he did have, which I had never yet known a man to have, was many identical white undershirts to wear under everything and to sleep in. Sometimes he kept them on while we made love if we didn’t make time to take everything off. His undershirts remained always perfect white, because they were so many as to go in a load of laundry all by themselves. Hot water, with bleach. They went in smelling like him and came out smelling like the laundry. I liked it so much that the water bill increased.

Nathaniel came home from work one evening and we made and ate yams together, and then he said that his sister Judith needed to stay with us for a little while. He said that she would be getting in from Indianapolis before he could get out of work; could I be here to let her in?

Of course I would be there—I hardly ever left.

I heard her coming up the stairs before she even approached our floor. I went down into the stairwell to meet her. The stairwell was made of dingy grays and beiges, with cigarette butts and leaves nesting in corners, having crawled in from outside. Below me was Judith, hauling a rolling suitcase up the steps behind her. There was no elevator in our apartment building. Fourth floor walk-up.

“Hello!” I cried. Judith looked up into my face and I spoke again. “Hi Judith!”

I went down to her. She looked a lot like Nathaniel: dark hair, hers very long in a braid she threw over her shoulder, a turned up nose, a very red mouth. She too was much taller than me.

“Hi,” she said. Even her voice sounded a certain amount like his. I stuck my hand out when I got to her, which she had to reorganize her shoulderfuls of bags in order to shake. The pause was long enough for me to think: Is this correct? Do women shake hands when they meet, alone?

Well, we had done it. I took a backpack from her and we ascended back to the apartment. “You’re not allergic to cats, I hope.”

“Slightly,” she said. “But I like them. My eyes just itch a little.”

“I don’t think there’s a lot of dander flying around,” I said. “We keep the apartment pretty clean.”

“It’s not the dander, it’s the spit,” she said.

The cats greeted us when we came in. They had so little other than doorjambs to rub themselves on, usually, that they set to it frantically with Judith’s things.

“Chubby,” she observed. Emilie sharpened her face again and again. The black rolling suitcase gathered an orange coat.

“She’s pregnant,” I said. I tried to recuse myself through total disclosure. “By her own brother. I wasn’t fast enough getting them fixed. I hope the babies turn out normal.”

“I think they will,” Judith said. Her eyes watered as she said this, which lent her an air of deep sincerity, though it was only her allergy. “I think that’s kind of normal for them.”

She scratched Emilie on the head and Emilie, overjoyed, fell over on her side.

“Look how she lets me touch her tummy!” Judith said, sinking her hand into the fur, thin enough on her plump belly that the pink showed through. “Maybe she doesn’t know.”

“I think she must know,” I said, although really I couldn’t be sure. I had assumed that she knew, in the way that animals, in their simplicity, understand everything they need to. Gustav knew, I thought, since he left her alone now. As far as I could tell. I had tried to keep a closer and more interpretive eye on them since their tryst.

“When is she due?” Judith said.

“In a month,” I said.

“I can’t wait,” Judith said. I tucked away my surprise at learning she planned to be a month in our home.

Judith went into the bathroom while I unfolded the blue futon for her. “Speaking of,” she said, poking her head back out. “Do you have a tampon I can borrow? Haha. I mean, have permanently.”

“I use a menstrual cup,” I apologized.

“I really, really need one,” she said, cringing. Her eyes, still watering, strengthened her case.

“I’ll go to the drugstore,” I said.

“You’re a lifesaver!” she said, and shut the bathroom door again.

It was, I realized as the wind cut my face, the first time I’d been out of the apartment in at least a day. At least. The last time I’d been out had also been an errand: the farmer’s market, where I went on Wednesdays and Nathaniel went on Sundays for produce. Eating nothing but perishables meant constant shopping. When I had lived in my mounds of detritus I had eaten meals of rice and pasta, mainly, which I kept in huge quantities, with crust-lidded samplers of novelty hot sauces. I went outside never for errands, but often for relief from my living space. I’d see, invariably, some cardboard box with books, rained on but dried out again, “FREE,” and come home with a few to put on top of the few dozen others stacked in overflow on top of the bookshelf. More than half of them I hadn’t yet read when I dumped them all into the recycling on moving out. I hope you know that books can be recycled. They’re only paper.

I didn’t know what size or absorbency or material or brand of tampons Judith liked, so I bought small boxes of several, plus a box of panty liners too.

“For company,” is what I always would say when buying an eyebrow-raising amount and variety of liquor. I imagined deploying the same excuse with the drugstore cashier. But I didn’t need to. It was self-checkout at a machine.

When I returned to the apartment Nathaniel was standing at the closed bathroom door talking to his sister.

“I have yet to see her,” Nathaniel said.

“I can’t come out until I’m plugged up,” Judith said. I looked at Nathaniel. Her sense of humor made me a little nervous. I passed her my shopping bag through the cracked door.

“Such variety,” she observed.

When she emerged, she took an appraising look around the apartment and said to Nathaniel, “Painter’s white. You’re so lazy.”

It was embarrassing, then, that I liked the walls: they had come to Nathaniel this way after the landlord had painted over whatever else. “I think it’s modern,” I said faintly.

“Pure white makes everyone look ten years older,” Judith said. “And look how it gets dirty.” She gestured to an out-pointing corner. There was a smudge of darkness at cat height, where they had rubbed and rubbed their faces. “You need it warmer. A tiny bit of pink.”

For dinner we had salads of arugula and pear and walnuts with pepper cracked on top. To get full from this we had to make a lot and heave portion after portion onto our plates. In the transfer from bowl to plate and plate to mouth a certain amount of arugula leaves, undressed and dry, would tumble like tree leaves in autumn. The cats waited under the table to catch them.

“Do you have any oil and vinegar?” Judith said.

“I could roast some mustard seeds,” I offered, embarrassed.

“Or—” She cooed at the thought. “An egg. Slices of hard-boiled egg would be good on this, don’t you think?”

“We don’t keep eggs in the house,” I said. “I’m really sorry—we should have thought… for a guest…”

Judith waved her hand at my face as if to scrub away my features. “Don’t apologize! I should have been prepared. He’s always been like this. Rabbit food and sanctimony. Anyway, supposedly it’s good for you.”

Nathaniel was ignoring her. I thought he probably thought she would stop, eventually, on her own, which she did.

That night, the living room became Judith’s room. The blue futon, unfolded, took up a lot of the space, and the unzipped sleeping bag she used for a blanket traveled around on the makeshift bed—indeed, the room. Her suitcase, on its side, lay open, and I flopped it closed whenever I walked by. Sometimes a cat would then shoot out from inside, seeming to accuse me, with its twitching tail, of prissiness.

Judith herself was kind to me. I didn’t know whether it was two-facedness that made her be mean to Nathaniel and polite to me. Or unfamiliarity. Or pity. I felt a little pitied when I heard, from inside the bathroom one morning, her teasing Nathaniel that she had heard us having sex the night before. Everything in every room could be heard from every other room. “If you hung stuff on the walls,” she told him, “it would muffle some of the sound. But maybe you don’t want the sound muffled.”

On the second Friday—not the first—since her arrival, Judith removed from her duffel bag a pair of Shabbat candles, and placed them on the small desk in the living room.

“Are we Jewish?” I asked, with my one finger clicking away at work.

“We are,” Judith said.

“I am, too,” I said, although it was true only in an oblique sense, the sense in which I was relieved of being a fully white person. I figured the same for them, with the names Nathaniel and Judith, but Nathaniel had never behaved religiously—this night the week prior, and neither had Judith.

She took a lighter from her pocket and lit the candles. Then she covered her eyes.

“I think you’re supposed to sing,” I said.

“I don’t know the song,” Judith said, still with her hands over her eyes, looking foolish.

Nathaniel, from the kitchen where he was cooking beets, began to sing in Hebrew. Wax dripped onto the desk, and I too covered my eyes.

Judith needed work, and there was plenty of mine to go around. Nathaniel set her up with a moderator account one night, and the next morning when he left for work I sliced a pineapple and set it between Judith and me while we began.

“God,” she said. “This stuff is hilarious. Who are these people?”

I watched Belle de Jour and burned my tongue on pineapple. After a couple of hours, Judith clapped her laptop shut with violence and stood up.

“I don’t know how you read this stuff all day,” Judith said. “It’s too awful. I don’t think I can bear knowing people try to talk to each other like this.”

She took her coat from under the curled body of Gustav and he skittered away into the bedroom. Emilie, at her slow plump pace, followed. “I’m gonna go walk it off a little.”

I was surprised and somewhat embarrassed to learn that Judith was doing the job in such better faith than me. “I don’t read them,” I admitted. “I just delete them all.”

Judith laughed on her way out the door. “What a gift for moderation you have.”

It wasn’t that Judith didn’t like our food, she said, just that she could not sustain herself on it.

“It takes getting used to,” I said. “Your body will eventually start trusting that it’s full on just plants.”

But she couldn’t make it through the days. She ate breakfast and lunch with me as we worked, and then began to work on her dinner plans. She made them with the online dating service. “Have you ever tried this thing?” she said to me. “You can set it to casual dinner dates or group friend outings.”

She left before Nathaniel got home. I spent my days with Judith and my nights with Nathaniel. I thought: they are the only pair that never spend time with each other, alone, and then I thought: because I am the only one who doesn’t leave the house.

“We already know each other,” Nathaniel said when I told him this. “It doesn’t grow with attention or shrink without it—it’s always the same and it never needs anything.”

The thing that made people smell similar wasn’t in the blood or the history, but in the environment: the food consumed, the detergent, the schedule of sex and sleep. Thus it was that Judith reported to me that I smelled like her brother, and I can report to you that she did not.

Sex was what she wanted to talk to me about. It wasn’t her fault, really: we only had one mutual acquaintance and there was only one area in which I stood to tell her anything she didn’t already know. She could tell me so much—in what order he had lost his baby teeth, how his accent had sounded in middle-school Spanish, what his allowance had been and what he had spent it on—but it seemed imprudent to ask, or against our home philosophy: these were things of which he had sloughed himself, by chance or choice, and they had not made it to our home.

We both sat on the futon, clicking. Judith exclaimed, “This person wants—” I won’t repeat it. I tried to ignore her like Nathaniel did, but it didn’t protect me from her like it did him.

“But that reminds me. I have a really gross question,” she said.

“Is it true,” she said, “with your crazy diet, what I’ve heard, about vegans, you know, like the purity.”

I said nothing.

“About the palatability.”

“What I’ve heard,” she said, and I banned a user, “is that from a vegan guy, you know, it tastes much better.”

“It tastes just the same as everyone else’s,” I said, boldly on the everyone, to show her I wasn’t prudish, or hadn’t been. I looked up at her and set my face.

“I think you’re lying,” she said, and tapped a finger to her red lips.

There was then an unpleasant lurch in my body. I imagined that my bowels were moving. I went into the bathroom for relief, but passed nothing. But for a good deal longer I sat in the tiny room, listening to Judith’s movements beyond the door.

“Hey, do you think something smells?” she called.

“I’m in the bathroom,” I said, meaning to imply I oughtn’t be spoken to. Only when she laughed and said, “No, it’s sickly sweet,” did I realize it sounded like my answer to her question. Embarrassed, I flung myself back into the living room.

“Something smells bad in your kitchen,” she said, and walked around it, yanking her head back in long, sniffing inhales.

“I don’t smell anything,” I said. Someone who never left the house, I thought then, was in unique danger of becoming blind to an offense. Judith reached with both hands onto the top of the refrigerator, which she could do on tip-toe. I had to drag one of the two kitchen chairs to stand on to reach such a height.

“Oh my God. Oh my—God—!”

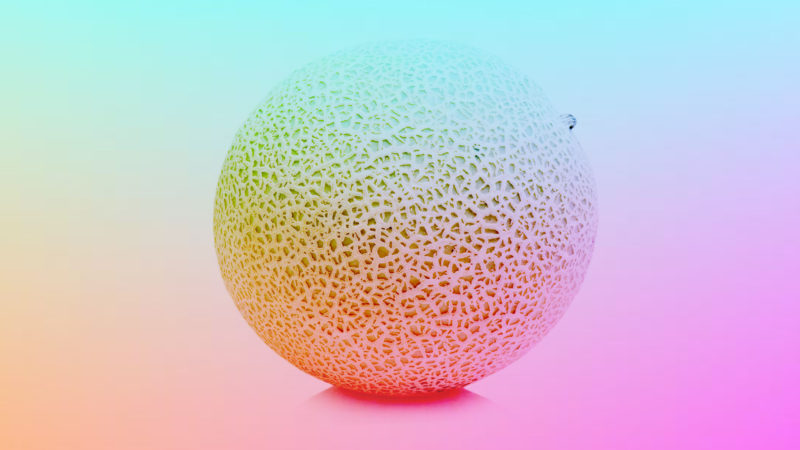

She retrieved a single cantaloupe, blotchy with rot. Two of her fingers had pushed clean through its soft head.

On Columbus Day we all took off work. Nathaniel stayed home and, in the daytime, in the light, the living room was too, too small for three of us, plus Gustav, who twitched, and Emilie, whose movements were slow and mysterious as she prepared herself. She was nesting among Judith’s things, we thought. Judith had set out further, purposeful piles of clothes in case Emilie could make use of them.

Nathaniel took me into the bedroom and in the cool, white light, made love to me. Alternately I covered my mouth to be silent and my eyes to block the light, which shone orange-pink through my fingers.

There came a prolonged cough from the living room, and finally, a sneeze.

“Jesus,” Nathaniel said, and pulled out of me. I hoped, silent and still, that he would overcome the moment and begin again, but he reached instead to take the condom off.

“Your period’s starting,” he observed. Embarrassing, to be informed by him.

“It’s early,” I said helplessly. “It’s like a week early.”

“It’s Judith, I bet,” he said. “I bet you’re syncing up with her.”

I put on my underwear and bra and pressed my legs tight together to walk to the bathroom. Judith, on her bed, was clicking, and her eyes were wet again. Just don’t read it, I wanted to tell her but didn’t. Just clear it all away. Then I remembered the allergy that made her look moved and unsettled no matter what befell her in our home.

I closed the door and sat on the toilet and a fat glob of blood dripped out of me, and then there was a wave of cramps. Then I heard a very small noise: I had interrupted Emilie. In the clean white tub she lay licking small, naked things. Only two of them. For that we were lucky. It could have been up to six or eight. They were pink and orange, and made tiny jerking movements like animatrons. Emilie licked them over and over with big swipes of her head.

She was almost finished—they were mostly clean, and she had eaten up most of the mess. She was smart to do it in the tub where I could help her clean it up, I thought.

“Hey, are you almost done?” Judith said, clear as if there were no door separating us. “I think I have my period.”

The kittens kicked their froggy legs out behind them to propel their faces into Emilie. Judith knocked on the door. “Can I come in?” she said, louder. I could see her single eye flashing in the keyhole, and I pressed my thumb into it, and felt the swell of my flesh into the cold space.