Loose Canons

“I don’t understand.”

Mr. Morris removed the boy’s paper from its folder and placed it on his desk. He looked up at the slender brown man in the ill-fitting suit fidgeting uncomfortably in the seat across from him. The boy’s father, Mr. Jenkins:

“It’s just I know my son… I mean I know what he is capable of.”

Mr. Morris nodded. Trying to explain to pitifully confused parents why their child had failed was surely the least pleasant of his duties as assistant dean of West Wesley Preparatory School. The situation was always that much more difficult when the boy in question was like this one and clearly bright. If troubled. Mr. Morris had reviewed the boy’s file and was convinced that the mistakes in his current work were intentional. But they were still mistakes.

“Uncle J was not a killer. He didn’t even no that man. They thought they could frame him because he had a reputation, because the police new he sold drugs. But that didn’t mean he was a killer. He just gave folks what they needed to dull the pane.”

“Now, Mr. Jenkins. I want you to know that we at West Wesley do not consider these scores to reflect, in an absolute sense, your son’s intelligence. But it is simply not possible for William to retain his current scholarship with grades like these.”

“Uncle J. was smart. He always made a prophet.”

Mr. Jenkins winced and clutched his stomach. If the information on William’s original application was correct, then the man was an attorney of some sort. William was not, as he claimed, from “the streets” but rather the undesirable edge of a comfortable suburb, one of five African Americans carefully selected by the scholarship committee to walk the corridors of West Wesley without mop, spatula, or competitive benefits. Much of what the boy had written was therefore lies. But sometimes there was a deeper truth to lies, if only in the need for them.

“Walked out the wrong door one knight is all that happened. Turned down the wrong alley and saw something he wasn’t supposed to sea. A mad swirl of dark shadows, clenched fists wrapped around pulled back triggers. A circle of seven angry gangsters and the barrel of a gun standing over an other man down.”

“I have circled all of the relevant passages so that—”

“I see them,” Mr. Jenkins said. He picked up the paper and held it in front of his face.

Mr. Morris stared at a blank page.

“A lot of folks would have just kept walking if they saw something like that. A lot of folks would have turned and ran. But Uncle J wasn’t like a lot of folks. He couldn’t stand to see no man pray upon the week.”

While Mr. Jenkins read, Mr. Morris considered his appearance: the jittery movements, the hunched shoulders, the frayed cuffs of his jacket. This was the fifth time this year a parent had been called in to discuss the boy’s academic performance yet only the first time Mr. Jenkins had seen fit to show up for the appointment. Mr. Morris knew from experience that very often when young boys took such precipitous downturns it was in response to negative stimuli in the home, a fact which made the decision to revoke the child’s scholarship all the more heartless, his own relationship to that decision so untenable.

“Let me reiterate, Mr. Jenkins. This is not an expulsion. Should the boy’s grades improve by the end of the semester, you have my assurance. I will personally see to it that his scholarship is reinstated.”

“‘Stay out of this,’ those gangsters shouted and pointed to the won lying at their feat. ‘This fool ain’t nothing but a worthless junkie. He ain’t your problem and this ain’t your fight.’”

“He’s got a lot of words in here saying two things at once,” Mr. Jenkins said finally.

Mr. Morris nodded. Actually, they said three things. They told a story.

“What I mean is, if you read it out loud, if you just listen to the sound of it, it makes perfect sense. So these are spelling errors but the logic is there.”

Mr. Morris frowned. Clearly Mr. Jenkins had no intention of discussing what his son had actually written. Yet nothing happened in a vacuum. That, in fact, was the school’s primary concern.

“Perhaps, if you just let him rewrite it…”

“I can’t do that. Quite frankly, there have been other incidents, minor disciplinary infractions, nothing serious in and of themselves. But given the violent imagery in some of your son’s work… Well. Some of his teachers are concerned it might constitute a pattern.”

This was understatement. The boy’s teachers were convinced he was a loose cannon and wanted to be rid of him all together. If it weren’t for Mr. Morris’s efforts to intercede on the child’s behalf, he would have been expelled.

“A pattern?”

“Blam! They tried to shoot him. Uncle J. dodged the bullet and Boom! Boom! Fought them off with his bear hand.”

“Profits,” Mr. Jenkins said softly. Like he was conceding something. “Profits and prophets…”

“Yes, Mr. Jenkins. Homophones.”

And not even that, really. Mr. Jenkins kept saying fate, perhaps to emphasize his point. When really it was more like fit and fête. “False cognates can be tricky.”

“But why do you think it’s so confusing for him?”

Mr. Morris sighed. All at once the full weight of the moment pressed in upon him. He’d read William’s work, had reviewed his file. He was still convinced that the boy had enormous potential. Yet in a few moments Mr. Jenkins would gather his belongings, walk out the door, and that would be that. The matter would be completely out of Mr. Morris’s control. Perhaps he would never see William again.

“Already he could here the sound of sirens behind him, police man coming with his flashing red lights. Those gangsters took off running but it was too late. The man on the ground was already gone.”

“You’re not understanding me,” Mr. Jenkins said. “I’m asking you an actual question. Perhaps it’s some sort of cognitive development issue, one that has not been properly assessed as yet. Because it seems to me that most people couldn’t even read a generation or two ago. Everything had to be sounded out. So how did they differentiate?”

“What?”

“Between profits and prophets.”

A quote from Shakespeare popped into Mr. Morris’s head:

You taught me language and my profit on it

“I’m asking you what you think.”

Mr. Morris winced. “I think, Mr. Jenkins, that to let your son rewrite this paper, to reinstate his scholarship without consequence, would be tantamount to a form of theft. It would not be fair to the other students, and quite frankly, it would not be fair to your son.”

He rose to his feet.

“Go home, Mr. Jenkins. Tell your son to look up false cognate in the dictionary. Then consider your options very carefully. Because I sincerely believe there is still a place for William at West Wesley. But he needs to understand that there are consequences to his actions. Just like everyone else.”

Mr. Morris waited for Mr. Jenkins to leave his office. Then he sat back down and brooded over the unpleasantness of his duties as assistant dean.

He was still an educator, after all. When was the calling more profound than when presented with a student like this one? The boy had talent; it took talent for an eighth-grade boy to fail with such resolution and Mr. Morris perceived this, was not so circumscribed by his duties as assistant dean that he no longer recognized art. But what if he was the only one who saw it? What if he was the father figure the boy so clearly needed? The steady hand, the guiding glance. The push.

“They said he was the killer and took him to jail. The man who razed me, only Papa I ever new…”

He could feel himself becoming agitated and sought solace in a picture of a smiling young woman he had placed on his desk years before: his wife. He stared at the photograph for a long time, trying very hard to focus on a single point, the glint in a woman’s eye.

“A misunderstanding was all it was. All Uncle J. was trying to do that knight was keep the piece…”

He blinked.

The Brown Bomber

So I’m a drug dealer now, Hank Jenkins thought. He shoved his son’s paper into the pocket of his jacket and walked down a long hall, still struggling to make sense of what had just happened. He’d lost an argument, although it hadn’t been much of one. Now he had to go home and tell his mother that William had lost his scholarship. Other arrangements would have to be made.

A group of boys marched by in uniform and Hank looked down at the floor, at the hem of his pants sagging over his shoes, laces skidding across the tiles in counter rhythm to his footsteps. He was wearing one of his old suits that his mother had kept for him but somehow it didn’t fit anymore; when he put it on that morning she’d muttered something about his needing time to grow back into it. Then smiled, straightened his tie, and pushed him out the door. As if coming to West Wesley to talk to his son’s dean was just the first in a series of simple tasks that led to him getting his life back and soon enough everything would be like before.

Hank had kissed his mother’s cheek just like he shook the dean’s hand and then made sure to look the man straight in the eye. All the while aware that every gesture, every word from his mouth, would be interpreted as the attempted correction of a misunderstanding he was not responsible for. Because what his son had written was not Hank’s story. He was no one’s Uncle J. Yet he had spent three months behind bars due to a single night in some ways similar to the one the boy described. Except Hank wasn’t a drug dealer. He was an attorney. And it wasn’t a prison where he’d served the majority of his sentence. It was a psychiatric ward.

Furthermore, the police were already there.

Hank stopped walking. He glanced over his shoulder as a terrible thought occurred to him. What if there was actually something wrong with William? Some synaptic breach in his nervous system, something passed down paternally?

But then he remembered that couldn’t have been it. Whatever else was wrong with Hank he’d always done well in school. If he’d passed along anything it would have been perfectionism, an obsessive need to exceed others’ expectations. He had been diagnosed with, among other things, OCD. It had been explained to him several times during the past year that that was why he was so easily agitated, why he didn’t always know when to leave well enough alone.

He pushed through a heavy wooden door and passed into the bright sunlight of the afternoon. He walked to the corner, sat on a bench, and watched a man push a mower across a rolling green lawn. Another group of children ran by, book bags bouncing on their shoulders as they jostled and pushed each other down the block.

As Hank watched them make their way across the street another terrible possibility roared through his mind. What if William was stupid? Too stupid to understand the opportunity he’d been given, too stupid to do the work required to maintain his place?

He took a deep breath. If William was stupid, then surely Hank could not be held responsible. That was something the boy must have inherited from his mother.

Hank’s ex-wife, the boy’s mother: perhaps the only one who’d never believed there was anything wrong with Hank. The one person who’d never wavered in her faith that he had not, as the police claimed, suffered some sort of drug-induced psychosis that night. No, instead she was furious, convinced he had done it with the sole intent of publicly humiliating her. How else to explain how a man of his intelligence would allow a misdemeanor charge of public urination to escalate into a felony altercation with the police?

All he’d been trying to do that night was take a pee. He’d gone to Henry’s Bar with his brother after work and, at some point, needed to use the bathroom. The urinal was broken so he stepped outside. Walked out the wrong door, turned down the wrong alley… Saw something he wasn’t supposed to see: a man on the ground being struck repeatedly by two police officers. Yet it was clear that the suspect, if that was what he was, had already been subdued. There was no reason to hit him anymore.

Hank had spoken without thinking, been punched in the groin for his trouble, and when he continued to protest was hauled off to jail. There he’d remained for the next twelve hours, at which point he was informed that the only one who’d be facing criminal charges was him. Because they were in him: the drugs. He knew that they were, even before they demanded he take the blood test.

Just like he knew what he had seen.

A bus pulled up to the curb. Hank waited until the doors opened then stood up and reached into his pocket. He found the coins his mother had given him, dropped them into a metal slot, and made his way down the aisle.

At first he’d thought about suing the city, filing a complaint for violation of his civil rights. But the only one who could corroborate his version of events was the man on the ground. Turned out he was a 24-year-old named Sam Brown whose criminal record would have made him useless as a witness, even if he had been willing to testify.

Hank found a seat and stared out the window, watching still more children move up and down the sidewalk.

They’re like little inkblots, Hank thought. Like the ones they’d shown him before his competency hearing: “Tell me what you see…”

Who knew how long his life might have gone on the way it had been if it hadn’t been for that night? Getting dressed for work each morning, kissing his wife at the door, smiling before his superiors, and snorting coke only every now and then at his desk behind a locked door. Walking among his co-workers without ever really being (in truth, he was always vaguely aware of this) wholly present.

The bus pulled to a stop at the entrance to City Park and Hank climbed down. There was a TV news van parked in front of the entrance and a small crowd had formed just inside the gate watching a reporter interview Mayor Montgomery about the brand-new recreational center that had been completed as part of an ongoing effort to revitalize the Southside. Hank kept his head down and pushed through the crowd. He walked through the park until he found his old dealer rolling a cigarette, perched on the railing of a bench. The man raised the cigarette to his lips and drew the edge of the paper along his tongue. When he saw Hank, he smiled in recognition and nodded to an orange fanny pack strapped around his waist.

Hank frowned. They’d sucked all the secrets out of him that night, drained his life like blood from a needle. He’s lost his job and his wife, and his license to practice law had been suspended. All that was left was an encroaching sense of oblivion and an overwhelming desire to get high. The only problem was how to pay for it. He didn’t have money or anything else to offer anyone anymore.

But he knew where he could get it.

“I’ll be right back,” he said. Then turned around, walked to the end of the block, and climbed the steps to his mother’s front door.

He found her in the kitchen, dressed in a housecoat and slippers, hips shaking in jagged spasms as she stood over the stove beating an egg in a small ceramic bowl. When she heard Hank come in she turned around and smiled.

“What did the man say, Hank?”

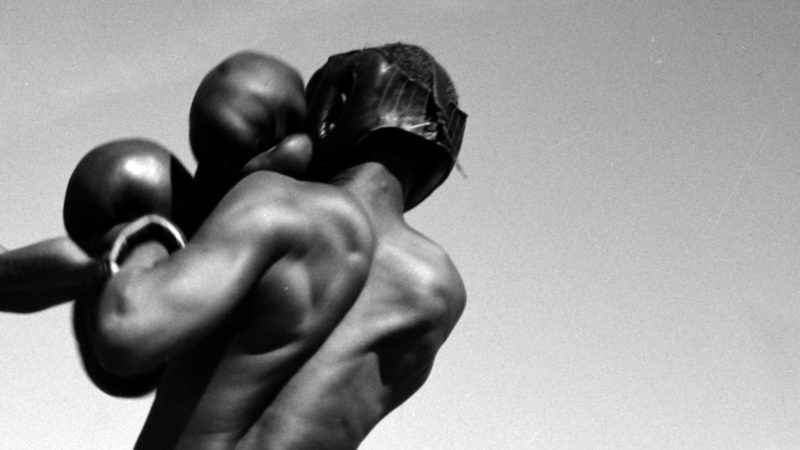

Hank looked away from her, toward the living room: the sea-foam shag carpet, the green paisley-print wallpaper, the low couch where his brother Daryl now sat, watching TV. Towering above the entire room was a life-sized portrait of Hank’s father back in his pro boxing days, bare-chested and glove-fisted as he crouched beneath a banner that bore what had been his professional moniker before he retired from the ring, settled down, and married Hank’s mother: The Brown Bomber.

Everything looked exactly the way it had when Hank was growing up.

“Hank? Did you talk to him? Get it all straightened out?”

Except for the tarp. Shortly after his father passed his mother had begun wrapping the room in plastic as a way to keep it clean for those rare occasions when company came to visit. Plastic runners crisscrossed the carpet, plastic covers enveloped the cushions of the couch, plastic sheeting draped the front of the glass-door cabinet that was stuffed to the bursting with souvenirs from his father’s career. Things that had sat untouched for years, things his mother couldn’t even be bothered to dust anymore. Things that could have been sold to help pay for Hank’s appeal.

He looked at his mother. “It’s all kind of mucked up at this point, Ma. I didn’t get back in time. The boy lost his scholarship and I can’t afford the tuition right now. You know very well it’s going to take some time for me to get back on my feet.”

His mother gasped: “You mean he’s been expelled?”

She was watching him the way his son used to in his old life, whenever he went out of town for a legal conference then came home and realized the boy had been expecting some sort of present. Like a child who’d been disappointed before.

“Not exactly. The dean said he was welcome to continue. I just have to pay for it.”

“Well, what does that mean? Some kind of payment plan?”

He looked around the living room. His mother was basically living in a mausoleum wrapped in plastics. Yet they both knew that there was thousands of dollars’ worth of memorabilia in the cabinet alone.

“We might have to sell some of Papa’s stuff.”

“What? You want me to sell Papa?”

“It’s not Papa, Ma.” Hank shook his head. “It’s Papa’s stuff. I’ve told you before, people remember Papa and some of them would pay a lot of money for these things you’ve got here. If we sold just a few of them we could probably get enough to cover the boy’s tuition. And Dean Morris promised William could get his scholarship back if he improves next term.”

“You believe that?” Daryl shouted from the couch. “Why should Ma pay all that money to send the boy to some fancy private school when he doesn’t even want to go?”

Hank frowned. It was still hard to look at his brother and not think about the night of his arrest. Daryl, after all, was the one who had insisted Hank meet him at Henry’s.

We never see each other anymore. Just come out for a couple of hours, it will be like old times. Unless you don’t want to hang out with me now that you—

“I wasn’t talking to you, Daryl.”

“Yeah, well, I’m talking to you.”

Daryl set his beer down on a vinyl cloth draped across the coffee table and stood up. He was still wearing his green uniform from work.

“Did it ever occur to either of you geniuses that maybe he’s just tired of being the only black kid at that school? It’s got him feeling all alienized and, can I be real for a minute? I think it’s starting to affect his mind.”

“Hush,” their mother said. She pointed toward the ceiling. “The boy can hear you, you know.”

Hank glared at his brother. He still remembered the look on Daryl’s face that night, when he ran outside and found Hank propped against the hood of that police car. The way he stopped and stepped backwards, telling Hank to be cool and not to worry. He said he’d meet him at the city jail with bail money and—

“Just stay out of this, Daryl. It doesn’t concern you.”

“Bullshit it doesn’t. Who do you think was looking out for the boy while you were gone, Hank? Me and Ma, that’s who. You can tell your snooty ex-wife I said so too. She doesn’t pay any attention to that child now that she’s got her new man. Just so long as he doesn’t get in her way. Ask Ma.”

“Quiet,” their mother said. “Don’t talk so loud.”

“William needs to go to school right here, Hank. Be around his own people for a change. I mean I understand you just want what’s best for him but fuck… Look what they did to you.”

Hank turned back to his mother.

“Ma? Are you listening to me? Did you hear what I said? Because it’s really quite simple. Either we find a way to pay or William will have to go to school somewhere else. Do you understand?”

“I think so, son.” She stared at the portrait of The Brown Bomber and sighed. “You want me to sell Papa…”

Hank shook his head. Oblivion, he thought.

He stared at The Brown Bomber’s gloved fists.

“I’ll be right back,” he said. Then turned around and marched up the stairs.

When he reached the second floor he walked down a dark hall to the bedroom where he and his brother had grown up. William was in there now; his ex-wife had consented to weekly visitations and Hank could hear the boy talking to someone on the phone. He leaned forward and squinted through the crack in the door, saw the boy’s legs swinging over the edge of a messy bed as he wound the phone’s cord around and around his forearm, another poster of his father glaring back at him from the boy’s closet door.

If only Papa was still here, Hank thought. The Brown Bomber would have known what to do, would have been willing to do whatever was necessary to make things right. The Brown Bomber, who had lived his life as if he truly believed he could smooth out the entire world with the force of his fist and the flat of his palm…

He took a deep breath and pushed through the door just as his son was hanging up the receiver.

“Who was that?”

“Mr. Morris.”

“The dean? He calls you at home?”

“Sometimes.”

Hank squinted. “Isn’t that… unusual?”

“I don’t know. Honestly, he’s never done it before. He said he just wanted to tell me how much he hopes I’ll be back next year. He thinks I have potential, whatever that means. He said he liked my paper.”

“That’s what he said?”

Back in Mr. Morris’s office Hank had said there was a logic to what William had written, but that was just the lawyer in him, trying to plead a case.

“What else does Mr. Morris say to you?”

“I don’t know.” The boy shrugged. “The usual stuff…”

“The usual stuff? Is there a reason he can’t talk to you about the usual stuff during school hours?”

“Not if I’m not going to school there anymore. He wants me to stay at West Wesley, says I need to buckle down and do my work so I can realize my full potential. He said he hates thinking about me winding up just another statistic.”

“A statistic, huh?” Hank nodded. He sat down on the edge of the bed next to his son and stared at the poster of The Brown Bomber, shirtless and gleaming as he clenched his fists and somehow managed to snarl and smile at the same time.

“You know, son. I realize that there are a lot of things we haven’t really had a chance to talk about yet. But the truth is… Well. Sometimes Caucasians can get some pretty wild ideas about what black people are like, the things we are capable of. That’s why we have to be very careful that our gestures are not misinterpreted.” He looked at the poster of his father and thought back to the night of his arrest, the young man he’d seen lying on the ground. “I tell you it’s dangerous.”

“What do you mean, Dad?”

“That story you wrote. I can’t help but wonder if, perhaps subconsciously… Do you think that when you wrote it you were just trying to say what you thought that man wanted to hear?”

“Who? Mr. Morris?”

“I’m only asking because I know you.”

“No you don’t.”

“I mean I know what you are capable of,” Hank said. “You know better than to make mistakes like that. And all that stuff about drug dealers and gangsters. You don’t associate with people like that. You weren’t raised that way. Why would you feel the need to write about things like that?”

William looked down at his shoe. He pushed his fingers through the laces and wound the bow around and around his thumb. He shook his head.

“Truth?”

“Well, of course. I’m your father, you can tell me anything.”

“I don’t want to go back there.”

Hank nodded. He placed his hand on his son’s back. “Son, I know it’s difficult now. But one day—”

“No, I mean I’m NOT going back,” the boy said. “I want to go to school right here, in the neighborhood. I already told Mr. Morris and when mom comes to take me home, I’m going to tell her too.”

Hank stared at his son. He realized he’d forgotten again: that it was not his decision anymore. He didn’t have the money to keep the boy in school and they both knew it. So what the hell were they even talking about?

Oblivion, Hank thought and shut his eyes. He stood up.

“Wait, Dad, where are you going?”

“I’ll be back.”

He walked out of the room and shut the door behind him, then stood alone on the other side listening to the sound of the TV downstairs.

So William had done it on purpose: let all those people at that school think he was a fool in an effort to have his way. Hank would never have dared do something so stupid as the boy because he knew his father would have beaten his ass. The Brown Bomber had ruled over his family with an iron fist, but Hank always told himself he would be a different kind of father, just like he’d worked so hard to be his own man. And what did he have to show for it? He’d lost his career, his wife and, apparently, control of his own son. All because something inside him would not allow him to lie about what he’d seen. It was a willful act, an assertion of selfhood that, because it seemingly occurred within a void, gave the entire turn of events an air of self-destruction, the illusion of choice. What kind of choice was his son making, he wondered. What had he taught his son about what it took to survive this world? Or what survival even meant?

After a while he wiped his eyes, took a deep breath, walked down the hall until he reached his parents’ immaculate bedroom.

As he pushed through the door his heart pounded, a sensation Hank instantly recognized as a strangely soothing vestige of the fear he’d felt as a child whenever he entered his parents’ room without permission. He walked to the edge of the bed and got down on his knees as memories of his father’s voice ran through him, like a shiver.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing, boy?”

Hank used to wince in fear every time he heard his father call his name but those were also the days when everything felt simple and safe, The Brown Bomber’s heavy hand hanging over everything like cloud cover. The man had been a groundskeeper for as far back as Hank could remember, but, lest anyone forget there had been a before, the entire house was a monument to someone who’d been strong enough to fight his way out of some salt-water southern slum with his bare hands.

“And I’ll beat the fool out of you too, if that’s what it takes.”

Hank threw back the edge of the comforter and felt around underneath the bed until he found a large hatbox. He pulled it toward him and removed the top. Inside it was an enormous pair of boxing gloves. He reached inside one and removed the small pearl-handled pistol that had been stuffed into the palm.

“Don’t even think about messing with my things. You hear me, boy? Cuz I will beat the tar outta you.”

He set the pistol on the floor and turned the glove over. A heart-shaped diamond brooch, a gold watch, and a dozen stray bullets tumbled onto the floor like spare change.

“I will beat the stupid.”

He put the first glove down, reached inside the second, and pulled out a fat roll of cash tied up in a gold money clip.

“I will beat the ugly.”

In truth, Hank had known where his parents hid their emergency stash of cash since he and his brother were twelve and ten years old, but would have never dared touch it while his father was alive. Now he removed the clip and counted out nine hundred dollars. It wasn’t enough to pay the boy’s tuition, but it was options. Enough for a decent suit, enough for a bus ticket out of town, enough to get his hands on whatever that man in the park had hidden in his fanny pack…

Hank hadn’t yet decided what it was he needed most.

“You hear me, boy?”

Hank looked down at his father’s glove. Profits and prophets, he thought. As different as he and The Brown Bomber may have been, he was still his father’s son, a product of how he’d been raised. That was why it didn’t matter what they did to him or how much the truth cost him. He was never going to lie about what he’d seen. In part it was because he was a good man, an honorable man, a man who despite his many flaws tried to do the right thing. But it was also because he knew what The Brown Bomber would have done to him if he ever found out Hank had backed down from a fight.

“Now get up off your knees, son. Act like you got some pride.”

Hank shoved the money into his pants pocket then put the pistol back in the glove and pushed the hatbox under the bed. He smoothed down the comforter and stood up just in time to hear the click of a door closing behind him.

“Son?” Hank said and got no response.

He’d barely made it halfway down the stairs when a voice called out, “It’s all right, you know,” followed by the low squeal of plastic. When he looked in the living room Daryl was still sitting on the couch, head pivoted away from the TV and smiling at him.

“I mean there’s nothing wrong with William if that’s what you’re worried about. He just doesn’t want to go to that school anymore.”

“How do you know?”

“He told me.” Daryl shrugged. “He tells me a lot of things. He and I talk.”

“Is that right?”

“Well, of course. Just trying to be a good uncle. And now that you’re back… I want you to know that I’m here for you, Hank. I mean that. Take you to meetings, whatever you need. You just let me know.”

Hank nodded. He thought about the way Daryl had smiled at him that night at the bar, the way he’d laughed when he pulled that pipe from his pocket.

“Relax, Hank. Let’s have ourselves a good time. You’re not at work and your wife’s not here. It’s just me, remember? Your brother.”

Here was a man who could handle his high. An uncle…

Hank reached into his pocket. “Why don’t you help me with this.”

“What is it?”

“William’s story, the one he turned in at school. Maybe you can make sense of it, seeing as how the two of you are so close.”

He stood near the couch and watched his brother’s lips move as his eyes scanned the page.

After a while Daryl said, “That’s crazy,” and put the paper down. He looked at Hank. “What?”

“I’m just trying to figure out where he got this stuff from.”

“Well, why are you looking at me like that? Hank?”

“Did you tell my son I was a drug dealer?”

Daryl frowned. “I knew it,” he shook his head. “That’s just typical, isn’t it? Everything’s got to be my fault. Right, Hank? No matter what happens, you always got to find some way to blame me.”

“What’s going on out there?” their mother shouted from the kitchen.

“I mean, here you are, one foot out of the fucking nut house and you’re going to try to make it my fault that your kid is screwed up?”

“What are you saying?” Their mother walked out wiping her hands on her apron. She smiled toward the ceiling. “He’s not screwed up. Nobody in this house is screwed up. Why would you say a thing like?”

“You’re missing the point, Ma. Which, by the way, is also typical. The point is Hank’s trying to blame me.”

“Just answer the question, Daryl,” Hank said. “Did you tell my son I was a drug dealer or not?”

“Your son?”

“Yes. My son.”

Daryl shook his head. He looked at his mother. He looked back at Hank.

“Fuck, Hank. No… I mean, of course not. I mean, I may have said some things. But nothing like what he wrote there.”

Hank turned to his mother. “Are you hearing this?”

His mother frowned. “Yes, son. I hear it.”

Then why don’t you do something, Hank thought. Why won’t you help me?

“It’s like this, see? You were gone and we didn’t even know when you were coming back. Naturally your son—my nephew—has got a lot of questions. And the truth is it’s fucking sad. I mean no offense but that’s the truth of it, it’s just fucking sad. So, I might have told him… some things. Just trying to prop you up a little bit. Trying to turn a negative into a positive some kind of way. Give him a little something to work with. I guess he must have got confused somehow…”

“So better to be a drug dealer than a so-called addict? Is that what you mean?”

“Yeah, so-called. Something like that.” Daryl shook his head. “Why not?”

Hank stared at his brother. He could feel his heart pound in his chest as scattered memories of the night of his arrest swirled in his mind like a flock of startled birds. There he was, back in that dark alley, staring at a red brick wall. Thinking about all the work he still had to do when he got home, thinking about how he was going to explain that to Daryl without hurting his feelings. That it had nothing to do with the company, it was simply time to call it a night.

“You feel better now, Hank? Is that what you wanted to hear?”

Next thing he knew there was a strange sound behind him: a thump, a muffled gasp, the shuffling of feet. And somehow, he felt compelled to turn around.

“Of course I didn’t tell him those things about you. What, just because you lost it you think I’m crazy too? You’re fucked up, man. Fucked up for even asking me that question.”

There he was, in the back seat of a police car. Bouncing over potholes as the sound of his own gasps merged with the wail of sirens, the flashing lights, the voices from the front—

Bastard junkie, sit

—all hurtling him toward the blank wall of the now.

“I’m on your side. You hear me, Hank? It’s me. Remember? Your brother.”

Hank balled his fist. He lurched forward and stumbled over an extension cord; the goose-necked lamp fell to the floor as Daryl stepped backwards and flinched.

“Watch yourself now, Hank. Don’t lose your cool.”

Hank gripped the collar of Daryl’s shirt with his left hand and swung wildly with his right. The impact of the blow knocked his brother against the cabinet of souvenirs. The unsheathed Brown Bomber stared down at his two sons as the glass door shook and shattered and the tarp fell across their bodies like a veil.

“Stop!” their mother cried.

Hank squinted at his brother crouched beneath him. Pieces of glass flickering like stardust in his hair, lower half of his face smeared with blood bubbling from his nose.

Like little inkblots, Hank thought and raised his fist.

False Cognates

William Jenkins stood on the front porch of Mr. Morris’s house, still unsure about whether he should have come. He was just about to retreat down the front steps when the door flew open and Mr. Morris appeared.

“William? What are you doing here?”

“I changed my mind,” William stammered. “I want to stay in school, take advantage of this opportunity to make something of myself.”

“Well, good,” Mr. Morris said. “But it doesn’t entirely answer my question.”

He looked around the quiet street. “How did you find my address?”

“I looked it up. Wasn’t hard to figure out where you live, where your wife works…”

“You shouldn’t have done that. It’s quite the violation… of privacy. You should come to my office during school hours.”

“I can’t if I’m not going to school there. Anyhow, you called me at home so I figured it was okay. I just wanted to tell you I want to stay. I’m willing to put the work in to make good grades, start acting right, taking my assignments seriously. Want to take advantage of this opportunity to make something of myself. Don’t want to be just another statistic.”

“Well, I’m glad to hear that. I do believe that if you apply yourself, nothing can stop you from achieving your goals. If your father can just come up with the money—”

“Awww, he doesn’t have any money,” William said. “Mr. Morris? All that stuff I wrote? None of it is true. I don’t have an Uncle J. My dad is the only one I know who’s ever been to jail and he’s not a drug dealer. He just had a nervous breakdown and lost his job is all… He’s just plain crazy.”

“Well, I am sorry to hear that,” Mr. Morris sighed. “On the other hand, I’m glad you trust me enough to—”

“I’ve got something, though. I found it in a hatbox under my grandparents’ bed. It’s what you call memorabilia. Probably worth a lot of money, maybe enough to pay my tuition.”

“Is that right?”

“It’s why I came over. I want to show it to you.”

Mr. Morris glanced back inside the house. His wife appeared in the hall, arms folded in front of her chest.

He turned back to William. “Son, I don’t think that now is the right time to—”

“Just have a look at it, will you?”

Mr. Morris sighed. He stepped out on to the porch and shut the door behind him.

“All right, son. What is it?”

William smiled and reached into his pocket.