Max and I wandered up Madison Avenue after school, scuffing the pavement with our sneakers, making fart noises with our armpits, angling the mirrors of parked cars in the hopes that drivers would see their own eyeballs during crisis moments in midtown traffic. At the twin phone booths outside Taso’s Pizza, we flicked the coin return levers but couldn’t get any change that didn’t belong to us. Then I had the idea to make a collect call from one pay phone to the other, inches away.

Max was magnificent. He let it ring twice before answering and he didn’t crack up when the operator told him that a Mr. Julius Rosenberg wished to reverse the charges.

“Why, yes, operator,” Max said graciously, thrusting his chin against the puffy collar of his down jacket to deepen his prepubescent voice, “I’d be more than happy to pay for a call from my dear old dad. I’ve really been missing his electric personality.”

We jabbered awhile on the phone company’s dime, grinning at each other and saying lame things like “long time, no see.” There was something remote and echoing about the way Max’s voice came to me: in one ear, he was very close; in the other, he was miles away.

When nobody came along and got annoyed at us for tying up both phones, we left the receivers dangling in their booths and went around the corner to Jolly Chan’s, where I had an egg roll and Max chugged half a bottle of soy sauce just because.

On our way out, we ran into Fathead, shlumping along Madison in that Eeyorey way of his. He was wearing his ridiculous chemical-warfare fatigues—“vo-looom-inous green pants that gather at the ankles,” as Max always mocked them. You could tell by the hopeful look on his face that he’d been following us. He was always following us.

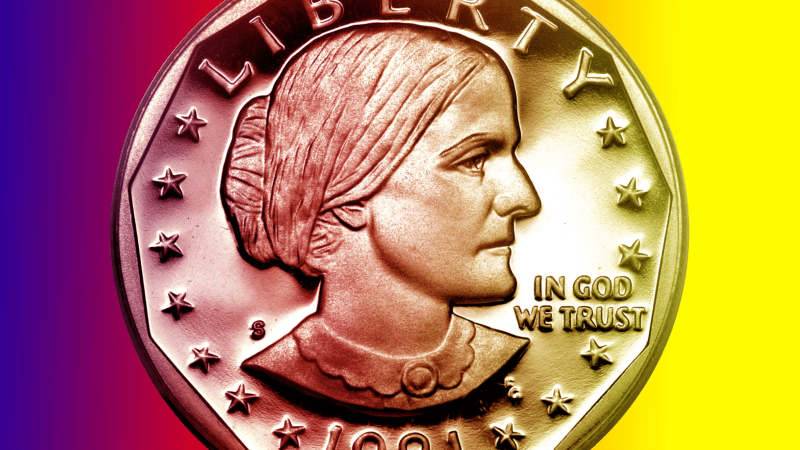

“Hi guys,” he said. “Is it okay if I hang out with you?” He was moving his hand around in the pocket of his big pea jacket, and I thought he was actually going to show us his stupid Susan B. Anthony dollar again. It was uncirculated and shiny, and he carried it around in a clear plastic slipcase he’d probably gotten from the Gimbels coin department. Sometimes he even brought along a little magnifying glass so he could point out the fine detail of Susan B’s hair (blah-blah-blah) and show you how the tiny letter D under the wreath meant the coin was minted in Denver.

Nothing in my life was as important to me as that silver dollar was to Fathead. There was no lamer hobby on the planet than coin collecting—even Fathead must have known that on some level—but something, maybe the way his hand sometimes wandered to that silver dollar when someone mentioned playing chess or hearts with their folks, made me think that the coin had been a gift from his mom, who had died in an electrical fire a couple years earlier. Some said her electric blanket had shorted out while she was in it. Others added that she was so zonked from her nightly bottle of Stoli that she hadn’t woken up until the smoke was too thick to escape.

One time when Tom Neale got sick of seeing that silver dollar and accused Fathead of having the hots for Susan B.—“that dead lady with the hideous haircut”—Fathead had shoved him against the water fountain and gone off to cry somewhere.

It was easy to see why Fathead missed her, because she really was one of the best moms in our class—far more interested in her kids than my checked-out parents, anyway. She was always making him these tasty tuna sandwiches with scallions, and she always cared about what he was up to. But she didn’t care too much, if you know what I mean. She gave him plenty of room to do whatever Fathead kinds of things he might want to do.

“Sure, you can hang out with us,” I now found myself telling him, and I think I meant it. It hadn’t felt like Max and I’d been doing much of anything, but now it did.

“You guys mind if I get an egg roll?” Fathead asked.

“Go ahead,” Max told him. “We’ll wait out here.”

“Cool.” He went into Jolly Chan’s, the blinds clacking against the glass door behind him.

Max glanced at Fathead through the open slats of the blinds, then at me. He didn’t have to say anything: the second the Chinese guy started taking Fathead’s order, the two of us went tear-assing up the block toward Fifth Avenue, choking on our laughter and looking over our shoulders. We still had nothing to do, but we wanted to not do it without him.

When we got to Fifth, we hung a right around the corner and rested our butts against an apartment building, panting for breath with our hands on our knees. A graffiti-tagged green bus lumbered past, trailing a dirty pennant of smoke.

You could see where some city workers had been ripping up the sidewalk across the street. The men had gone home, but they’d left behind a big hole surrounded by a flimsy orange fence made of small plastic circles, rows and rows like those six-pack rings that seagulls choked on.

There was something wrong with the city’s insides. Four water mains had burst in the past three months, each in a different part of Manhattan. Flash floods coursed through lobbies. People and things got wet and damaged.

What puzzled me was the randomness of it all. The exploding pipes were a lot like Dad’s plantar warts, which he scalded each night with a cotton puff dipped in acid; the virus was gliding around in the bloodstream, and you never knew where it would pop up next.

Two of the water-main explosions had happened just a few blocks from our house. The first, under a crosswalk on Eighty-seventh Street, flooded the Papaya King basement, nearly drowning a stock boy who couldn’t swim. The second break was even bigger. On one of the coldest days of the year, a big fat pipe had burst outside Loews Orpheum, and an upside-down waterfall surged out of the sidewalk, pinning a Ford Pinto against a parking meter. By the time I went to look at it the next day, the whole corner of Eighty-sixth and Third was an unskatable ice rink, the frozen turmoil of its surface ringed by blue police barricades and flapping yellow tape. The freezing water had held fast the body of the Pinto, jailing it behind a fanged fringe of icicles.

But the hole that Max and I saw on Fifth Avenue hadn’t been caused by any explosion. It had just appeared, the way some holes do.

“Let’s check it out,” Max said. “Maybe they left behind a hard hat or something.”

We crossed to the Central Park side of the avenue, and as we got close we heard the noise: a long low hiss like when you let the air out of someone’s bicycle tire. More curious than ever, we leaned over the orange fence, peering down for no more than a second before the heat rushing upwards from the hole struck us in the face and made us jerk our heads back.

“Shit,” Max said. “That’s hot!”

“Yeah,” I told him. “But at least it’s a dry heat.”

We stuck our heads out again, more slowly this time, and blinked into the hole. About six feet down was a huge sizzling pipe, maybe half the width of a Checker cab. Exposed on all sides and hissing with heat, it ran in a straight shot from the uptown side of the hole to the downtown side. It was brand new. Not a scratch on it, not a flake of rust.

“Wow!” I said, before I could stop myself. I hated when I said, “Wow.” It sounded so dorky.

Max hawked up a blob of phlegm and spat it down onto the pipe. It sizzled and vanished. I tried it, too, but kept missing. It was so frustrating. My spit wasn’t as chunky as his.

Lazily, Max spat a bull’s-eye on the pipe again to show me he could.

“You know,” I said, hoping to change the subject, “I bet that thing’s hot enough to fry an egg on.”

Max looked at me. “You figure?”

We went and got a dozen eggs from a deli on Madison. Before we paid, I was careful to open the carton for inspection, the way my mom always did. Standing in front of the humming freezer, I lifted each egg one at a time, rotating it in the light to make sure it wasn’t cracked. This seemed to offend the deli owner, a squat Greek guy with flecks of gray in his mustache.

“You don’t got to look at my eggs, boy,” he said. “I don’t sell broken food.”

The pipe was still hissing away when we got back. I gently cracked an egg on the sidewalk and allowed the white goop to ooze off until I had the yolk isolated in half a shell. Leaning way over the fence, I tipped out the yellow and watched it plop down onto the pipe, where it sizzled sloppily down the curved metal and scudded off into the dirt. Again and again I tried, without any luck. I wanted badly to be the first to fry one up.

Max didn’t throw any eggs. He stood still with a single brown one in his palm, watching me fail. When I’d tossed four of my six, he said, “You really think you can do it from way up here?”

I wiped my hands on my jeans. “What, you wanted to actually go down there?”

Max eyed his egg, moved his tongue around in his cheek. “I was thinking of it.”

“Yeah, me too,” I said. “I just wanted to sort of practice up here first.”

Down we went. We slid the egg carton under the plastic fence and clambered over it, using the little orange rings for footholds. Once inside, we gripped the wooden frame of the fence and let our legs and upper bodies dangle into the hole. Max let go first, and seemed to land all right.

“Come on already, ” he said from below. “What’re you waiting for?”

I hung there a minute, listening to the big pipe scald the air behind me. Finally I let my fingers slip and dropped straight down, scraping my cheek painfully along the side of the hole — anything to keep from getting scorched by that pipe. But my knees buckled when my Keds hit bottom and Max had to grab me to keep me from falling against the burning metal.

He steadied me, and for a second we were still, his hands on my shoulders, our faces just a few inches apart. Neither of us was too happy about that, so we quickly moved off to opposite ends of the hole.

It was horribly hot down there, and the hissing made it feel even hotter. We took off our down jackets. The pipe, which was suspended about a foot above the bottom of the hole and came up to our waists, was even bigger than it had seemed from up on the street. Without looking at each other, Max and I each hunched forward and set about trying to fry the perfect egg.

My yolk stayed in place this time at the top of the pipe, but now the white gave me trouble, dripping down both slopes at once and instantly drying into a flaky brown mess. Max was having a much better time of it. He seemed to have coaxed his fried egg into a nearly flawless sphere, prodding it with fragments of shell, or maybe his bus pass. I couldn’t tell for sure how he did it. He had his arm in front of his work, to keep me from copying.

A couple feet above our heads, two mothers with strollers strode by, gabbing in cheery voices. One of them said that some other mother’s kid was “bad news.” A jogger in gray sweats huffed past. Nobody looked down.

My eggs were a disaster. This was no good. True, the collect call had been my idea, but ditching Fathead had been Max’s, and so was climbing down to do the frying, and he’d been the only one to spit on the pipe, and now his egg was coming out better than mine.

“We’ve got a problem,” I said, trying to sound really earnest.

Max didn’t look up from his cooking. “What is it?”

“How’re you going to eat that?”

“Eat it?” He stared at me.

“Yeah. How’re you going to eat it?”

It only took him a second to recover. “Ohh, you mean what am I gonna use for silverware. I thought I’d just kind of scrape it off with my keys or something.”

“Yeah, but what’re you gonna do for a plate?”

I had him there, so we climbed out of the hole and went back to the deli. This time we got two cups of coffee, loaded up with four sugars each because we both secretly thought coffee was gross, along with a couple of aluminum take-out plates, plastic utensils, salt packets, and another half-dozen eggs.

“Hey,” the deli guy called after us as we were leaving. “What happen to those egg I already sell you?”

“They broke,” Max said.

“Yeah, faulty merchandise,” I added. “Must’ve had some tiny cracks I didn’t see. The light is very poor in here, you know.”

On the way back to our hole, I pointed out to Max how dumb we’d been to blow all our money without getting even a small package of bacon.

He stopped and gaped at me. “That would’ve been sooo cool!” he said, his cheeks reddening with excitement, and at that moment I would have given anything to get us that bacon.

Dropping into the hole was easier the second time around. Unfortunately, the moment the cooking started up again, my damned yolk broke, and as I was laboring to salvage some kind of half-scrambled omelet, a shadow fell over my end of the pipe. When I looked up, there was Fathead’s big old beachball noggin poking over the orange fence. He saw me see him, saw that I had no plans to acknowledge his existence, and moved his shadow down the pipe from me to Max.

Max flinched at the sudden shade and glanced up. “Oh, it’s you,” he grumbled. “Go away.”

Fathead didn’t listen.

“Cool pipe,” he said instead, leaning on the fence. “But what’s with the freaky sizzling sound? Doesn’t that mean the pipe is under some big-time pressure?”

I still didn’t acknowledge him, but I did stop and listen, one more time, to that searing hiss, which had burnt away virtually all street sounds ever since we’d first dropped into the hole. That hissing noise was all around us, like a mist or a gas you couldn’t see. It was hard to know if it was supposed to sound like that.

“Hey Fathead,” Max said. “Got any money on you?”

Fathead’s eyes got all big and panicky for a second and he pushed himself away from the fence, slapping frantically at the pocket of his pea jacket. Then, apparently finding what he was looking for, he breathed out a relieved sigh and leaned forward again.

“Nope,” he said. “Spent my last dollar on that egg roll. Why’d you guys take off, anyway? It wasn’t my fault it took so long.”

Max tapped his plastic knife on the steampipe. “Fathead?” he said. He spoke the name slowly, even patiently.

“Yeah?”

“Go away. Can’t you see we’re working here?”

I looked up again, eyed Fathead closely. He was hanging his arms way over the orange fence, trying to get close to us. The bendy plastic gripped him under the armpits and shaped itself around three sides of his body, hugging him like a net.

“Wait a second,” he said suddenly. “I hope I didn’t give you guys the idea just now that I was scared of that pipe. Not at all.” When we didn’t respond, he said, “So is it alright if I come down there with you?”

“Well, we’re kind of having a potluck down here,” I told him, shaking my head ruefully, as if the matter were out of my hands. “And I’m not sure it would be fair to all the other guests if we just let you join us without bringing a little something to the table.”

Fathead laughed. A small, nervous laugh. “Like what?”

“Like, oh, bacon, for instance.”

“Oh, come on. I told you I don’t have any money.”

“Who said anything about money?” I asked. “Just steal it.”

“Yeah,” said Max, gesturing at the mess of sticky eggshells and salt packets and spilt coffee lying in the dirt at our feet. “We stole all this stuff.”

“Come on, guys, please. Can’t I just come down and watch?”

I hated when Fathead whined. “Bacon!” I told him, turning back to my mangled egg. “That’s all I have to say to you: Bacon.”

Fathead trudged away, dragging his shadow behind him. I watched it glide along the pipe and up the dirt wall before slipping out through the holes in the orange fence. It seemed to take its time, as if it wasn’t sure it wanted to hang out with him either.

“You’re nuts if you think Fathead’s gonna steal anything,” Max told me. “He’d never do it, not in a million years.”

“You’re right. That’s how I know he’ll pay for our bacon.”

“But he just told us he was out of money.”

“Yeah,” I said, “but that’s ’cause he wanted us to forget all about that special someone in his life, that extra special lady who’ll sacrifice herself to buy stuff for him if he wants it bad enough.”

Max looked at me blankly. “Who’s that?”

“Oh, you know,” I said, prouder of myself than I’d been in a long while. “Old Susan B.”

Max stared at me with his head cocked to one side, as if he couldn’t quite believe my mind had thought of something so ingeniously awful. His face broke out in a big, puzzled smile.

But he wasn’t yet prepared to cede the field to me. For as I watched, he pulled out his bus pass with a flourish and used it, ever so delicately, to flip his egg.

Truth be told, it looked almost tasty — over-easy and more or less round. Turning his aluminum plate bottom-side-up so the wrinkly sides wouldn’t get in the way, he deftly slid his egg onto it with his plastic knife. He was being almost dainty. After a careful sprinkling of salt, he sat down Indian-style on the bottom of the hole, rested the plate on his left knee, and prepared to dig in.

I looked at my own tortured egg on the pipe: charred around the edges, raw and glisteny on top. Revolting, yes, but there was no turning back now. I scraped what egg I could into my take-out plate with my knife and quickly tipped the whole disgusting mess into my mouth.

I swear, that half-soft lump of egg felt so much like a squashed canary in my mouth that I even thought I could feel its beak scraping that bell-clapper flap of skin at the back of my throat. I swallowed hard, gagged, swallowed again. Then I closed my eyes tight and counted to ten to see if I would die.

When I opened them again, the first thing I saw was Max sitting cross-legged on the ground like a yogi, grinning from ear to ear, savoring his perfectly cooked egg. I don’t know whether he really thought it tasted all that good or not, but he sure said “Mmmm” a lot, and he kept patting his belly.

That’s when Fathead came back. “Hey fellas,” he called down to us in a weak voice I could barely hear over the hissing.

For a second, I thought Fathead had let me down, but when he leaned over the fence, I spotted the very thing I was looking for. Sticking awkwardly out of a front pocket of his pea jacket was that glorious yellow-and-red package—the bacon!

“You didn’t say what kind you wanted,” Fathead said morosely, “so I got this hickory-smoked stuff. I hope that’s okay.”

“You bet it’s okay!” Max told him. “C’mon down.” And turning to me he said, “This is going to be soo cool, Damon. I mean, think about it: the scent—the farm-fresh scent—of hickory, wafting down Fifth Avenue toward the Guggenheim!”

I don’t know if I’d ever seen him so happy. He was shaking his head at me with a kind of awe, his cheeks practically as red as his down jacket. I would’ve eaten half a dozen of those putrid eggs just to see that look on his face.

Fathead did an okay job lowering himself into the hole, though I could’ve sworn the pipe shook when his big old combat boots landed in the dirt. Pulling the Oscar Mayer package from his pocket, he murmured, “Well, anyways, here’s your bacon, guys.”

Now that was a perfectly fine thing for him to say, but there was something wrong with the way he looked when he said it. His neck was all droopy, like it didn’t have a bone in it, and his eyes were kind of milky, and his voice sounded broken or something. It sort of depressed me, and made me not want him or his bacon around anymore.

Max, I don’t think he noticed all that, because he went ahead and asked Fathead a pretty harsh question: “So, big guy, how many dollars does a pack of bacon like this go for? I mean for someone who doesn’t steal it the way you did.”

Fathead slipped his hand into that front pocket of his pea jacket again, out of habit I guess, and the thing is, I saw him not feel anything in there. When his hand came out all empty, he looked down at the dirt, and his lips did a funny kind of twitch. I couldn’t see his eyes.

“A little under a buck,” he said, very quietly. The way he said it, I could tell he was thinking about the Susan B he’d just parted with. That got me wondering, and I wondered if he wondered how that Greek deli guy was treating his mom’s coin. Whether he’d just tossed old Susan B. under the tray in his cash register with all the other weird currency he got, Kennedy half-dollars and things, or if he’d Scotch-taped her to the dirty tiled wall behind him as a trophy, next to the first dollar bill he’d earned in that store. I wondered if, from now on, every time Fathead went into that deli to buy Wacky Packages, he would have to look at her hanging up there on that wall, taped next to those cheesy old blue-and-white postcards from Crete.

It might’ve been the heat, but Fathead’s eyes were almost teary as he ripped open the bacon package with his teeth. When I tried to give him a hand, he shook me off roughly and said, “I got it. Okay?”

You should’ve heard the sizzling sound that went up when Fathead put that whole slab of bacon on the pipe. It was deafening, like the crashing of grease-swollen thunder clouds, and I probably would’ve been scared, except the bacon immediately launched itself off the far side of the pipe and into the dirt. Max gave out an obnoxious cackle, which made Fathead rush to retrieve the bacon. Lying on his side on our half of the hole, he stuck his thick left leg under the pipe, his thigh no more than three inches from its scalding surface, and worked the pink and white lump back to our side with his boot. When he stood up with it in his hands, the oily slab had a crust of dirt and gravel clinging to its surface.

I pulled a face. “I hope you don’t expect us to eat that now.”

“Yuck,” Max said.

“It’ll be fine,” insisted Fathead. “I’ll just brush it off. It’ll be fine, I swear.” He was practically panicking, and I was afraid he was really going to cry. “Look, it’s coming off,” he kept saying, desperately rubbing the bacon on those chemical-warfare pants of his. It left a funny-looking stain.

“Lookit, Fathead!” guffawed Max, pointing to the grease smear. “You’ve got the Pelopo neeesus on your leg! Right there on your “vo-looom-inous green pants that gather at the ankles!”

“Okay, okay,” he said, his voice cracking, “but look! You can hardly even tell it fell in the dirt. We’ll just cook it right up.”

He was really making me depressed.

“Listen,” I told him, “I’m not really too hungry anymore. I mean, I just got through eating an egg and everything.”

“Yeah,” said Max. “I wanna leave some room for dinner, too.”

I started to climb out of the hole. So did Max.

“Come on, guys,” Fathead kept pleading. “Just hang on a second! This bacon will be totally cool. I swear.” He was really whining now, and I couldn’t get out of there fast enough.

When Max and I were standing up on the street again, I leaned over the fence and looked down at Fathead in his casket-shaped hole. At his feet was part of the greasy bacon wrapper, clear plastic like the slipcase he’d always used to protect Susan B.

“Seriously, guys,” Fathead said. “Why don’t you come back down? There’s like five pieces of bacon here that don’t have any dirt on them at all!”

“That’s fabulous,” I said. “That means you can have exactly five pieces to yourself. What could be more fair than that?”

Jesus, Fathead was depressing me. He was just standing down there alone, looking up from that hole with those sad milky eyes, hugging that lump of stripy pig fat to his chest, cradling it.