Before BP destroyed habitats and livelihoods in the Gulf, Monsanto landed in India. A filmmaker on the time of the GM cotton suicides, and what was learned.

Our products provide consistent and significant benefits to both large- and small-holder growers. In many cases farmers are able to grow higher-quality and better-yielding crops.

—Monsanto, Pledge Report, 2006

It was December 2006, and we had barely arrived when a funeral procession came around the corner of an alley running between whitewashed walls, shattering the torpor of the little Indian village under the burning sun. Wearing the traditional costume—white cotton tunic and trousers—the drummers led the group toward the nearby river, where the funeral pyre had already been set up. In the middle of the procession, weeping women desperately held on to robust young men with somber faces carrying a stretcher covered with brilliantly colored flowers. Gripped by emotion, I glimpsed the face of the dead man: eyes closed, aquiline nose, brown mustache. I will never forget this fleeting vision, which stains Monsanto’s great promises with infamy.

Three Suicides a Day

“Can we film?” I asked, seized by sudden doubt, as my cameraman questioned me with a motion of his head. “Of course,” answered Tarak Kate, an agronomist who heads an NGO specializing in organic farming who was traveling with me through the cotton-growing region of Vidarbha, in the southwestern Indian state of Maharashtra. “That’s why Kishor Tiwari brought us to this village. He knew there would be a funeral of a peasant who had committed suicide.”

Kishor Tiwari is the leader of the Vidarbha Jan Andolan Samiti (VJAS), a peasant movement whose members have been harassed by the police because they have insistently denounced the “genocide” caused by genetically modified Bt cotton in this agricultural region, formerly celebrated for the quality of its “white gold.” Tiwari nodded when he heard Kate’s answer. “I didn’t say anything to you for security reasons. The villagers inform us whenever a farmer has committed suicide, and we come to all the funerals. Right now, there are three suicides a day in the region. This young man drank a liter of pesticide. That’s how peasants kill themselves: they use the chemical products the transgenic cotton was supposed to enable them to avoid.”

As the procession headed off toward the river, where the body of the young victim would soon be cremated, a group of men approached my film crew. They looked suspicious, but Tiwari’s presence reassured them: “Tell the world that Bt cotton is a disaster,” an old man said angrily. “This is the second suicide in our village since the beginning of the harvest. It can only get worse, because the transgenic seeds have produced nothing.”

“They lied to us,” the head of the village added. “They had said that these magic seeds would allow us to make money, but we’re all in debt and the harvest is nonexistent. What will become of us?”

We then headed toward the nearby village of Bhadumari, where Tiwari wanted to introduce me to a young widow of twenty-five whose husband had committed suicide three months earlier. “She’s already talked to a reporter from the New York Times,” he told me, “and she’s ready to do it again. This is very unusual, because usually the families are ashamed.” Very dignified in her blue sari, the young woman met us in the yard in front of her modest earthen house. The younger of her two sons, one three years and the other ten months old, was sleeping in a hammock that she rocked with her hand during the conversation, while her mother-in-law, standing behind her, silently showed us a photograph of her dead son. “He killed himself right here,” said the widow. “He took advantage of my absence to drink a can of pesticide. When I got back he was dying. We couldn’t do anything.”

As I listened to her, I recalled an article published in the International Herald Tribune in May 2006 in which a doctor described the ordeal of the sacrificial victims of the transgenic saga. “Pesticides act on the nervous system—first they have convulsions, then the chemicals start eroding the stomach, and bleeding in the stomach begins, then there is aspiration pneumonia—they have difficulty in breathing—then they suffer from cardiac arrest.”

Anil Kondba Shend, the husband of the young widow, was thirty-five, and cultivated about three-and-a-half acres. In 2006, he had decided to try Monsanto’s Bt cotton seeds, known as “Bollgard,” which had been heavily promoted by the company’s television advertising. In those ads, plump caterpillars were overcome by transgenic cotton plants: “Bollgard protects you! Less spraying, more profit! Bollgard cotton seeds: the power to conquer insects!” The peasant had had to borrow to buy the precious seeds, which were four times more expensive than conventional seeds. And he had had to plant three times, his widow recalled, “because each time he planted the seeds, they didn’t resist the rain. I think he owed the dealers 60,000 rupees. I never really knew, because in the weeks before his death he stopped talking. He was obsessed with his debt.”

What came next was an incredible scene in which dozens of peasants spontaneously declared, one after another, the amount of their debts.

“Who are the dealers?” I asked.

“The ones who sell transgenic seeds,” Tiwari answered. “They also supply fertilizer and pesticides, and lend money at usurious rates. Farmers are chained by debt to Monsanto’s dealers.”

“It’s a vicious circle,” Kate added, “a human disaster. The problem is that GMOs are not at all adapted to our soil, which is saturated with water as soon as the monsoon comes. In addition, the seeds make the peasants completely dependent on market forces: not only do they have to pay much more for their seeds, but they also have to buy fertilizer or else the crop will fail, and pesticides, because Bollgard is supposed to protect against infestations by the cotton bollworm but not against other sucking insects. If you add that, contrary to what the advertising claims, Bollgard is not enough to drive off the bollworms, then you have a catastrophe, because you also have to use insecticides.”

“Monsanto says that GMOs are suitable for small farmers: what do you think?” I asked, thinking of the firm’s claims in its 2006 Pledge Report.

“Our experience proves that’s a lie.” said the agronomist. “In the best case, they may be suitable for large farmers who own the best land and have the means to drain or irrigate as the need arises, but not for small ones who represent 70 percent of this country’s population.”

“Look,” Tiwari interrupted, spreading out a gigantic map he’d gone to get from the trunk of his car.

The vision was startling: every spot in what is known in Vidarbha as the cotton belt was marked with a death’s head. “These are all the suicides we’ve recorded between June 2005, when Bt cotton was introduced into the state of Maharashtra, and December 2006,” the peasant leader said. “That makes 1,280 dead. One every eight hours! But here, where it’s blank, is the area where rice is grown: you see there are practically no suicides. That’s why we say that Bt cotton is in the process of causing a veritable genocide.”

Kate showed me a small space where there were no death’s heads. “This is the sector of Ghatanji in the Yavatamal district,” he said with a smile. “That’s where my association is promoting organic farming among five hundred families in twenty villages. You see, we don’t have any suicides.”

“Yes, but suicides of cotton farmers are nothing new; they existed before GMOs came on the scene.”

“That’s true. But with Bt cotton they’ve greatly increased. You can observe the same thing in the state of Andhra Pradesh, which was the first one to authorize transgenic crops, before it got into a battle with Monsanto.”

According to the government of Maharashtra, 1,920 peasants committed suicide between January 1, 2001, and August 19, 2006, in the entire state. The phenomenon accelerated after Bt seeds came on the market in June 2005.

Hijacking Indian Cotton

Before I flew off to the huge state of Andhra Pradesh in southeastern India, Kishor Tiwari was eager to show me the cotton market of Pandharkawada, one of the largest in Maharashtra. On the road leading to it, we crossed a column of carts loaded with sacks of cotton pulled by buffalo. “I warn you,” Tiwari said, “the market is on the edge of exploding. The farmers are exhausted, the yields were catastrophic, and the price of cotton has never been so low. This is the result of the subsidies the American administration gives its farmers, which has a dumping effect on world prices.”

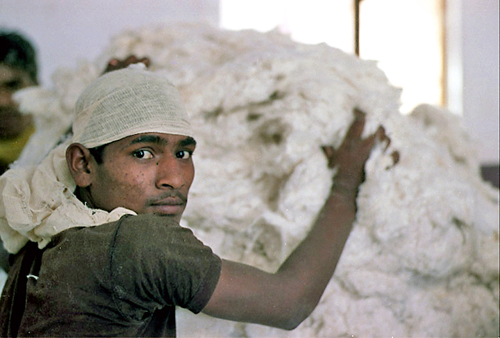

We had barely gone through the imposing gate into the market when we were assailed by hundreds of angry cotton farmers who surrounded us so we couldn’t move. “We’ve been here several days with our harvest,” one of them said, brandishing a ball of cotton in each hand. “The dealers are offering a price that’s so low we can’t accept it. We all have debts to pay.”

“How much is your debt?” Tarak Kate asked.

“Fifty-two thousand rupees,” the farmer answered.

What came next was an incredible scene in which dozens of peasants spontaneously declared, one after another, the amount of their debts: 50,000 rupees, 20,000 rupees, 15,000 rupees, 32,000 rupees, 36,000 rupees. Nothing seemed able to stop this litany running through the crowd like an irresistible tidal wave.

“We don’t want any more Bt cotton!” yelled a man whom I couldn’t even pick out from the crowd.

“No!” roared dozens of voices.

Kate, clearly very moved, asked: “How many of you are not going to plant Bt cotton next year?”

A forest of hands went up that, miraculously, the cameraman, Guillaume Martin, managed to film, even though we were literally crushed in the midst of this human tide, which made filming extremely difficult. “The problem,” said Kate, “is that these farmers will have a lot of trouble finding non-transgenic cotton seeds, because Monsanto controls practically the entire market.”

Beginning in the early nineteen nineties in fact, at the same time as it was setting its sights on Brazil, the world’s second largest soybean producer after the United States, Monsanto was carefully preparing the launch of its GMOs in India, the world’s third-largest cotton producer after China and the United States. An eminently symbolic plant in the country of Mahatma Gandhi, who made the growing of cotton the spearhead of his nonviolent resistance to British occupation, cotton has been grown for more than five thousand years on the Indian subcontinent. It now provides a livelihood for seventeen million families, mainly in southern states (Maharashtra, Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh).

Monsanto also organized several trips to its St. Louis headquarters for Indian journalists, scientists, and judges.

Established in India since 1949, Monsanto is one of the country’s major suppliers of phytosanitary products. There is a large market for herbicides and especially insecticides, because cotton is very susceptible to a wide variety of pests, such as bollworms, wireworms, cotton worm weevils, mealybugs, spider mites, and aphids. Before the “green revolution,” which encouraged the intensive monoculture of cotton with high-yield hybrid varieties, Indian farmers managed to control infestations by these insects through a system of crop rotation and the use of an organic pesticide derived from the leaves of the neem tree. The many therapeutic properties of this tree, venerated as the “free tree” in all the villages of the subcontinent, are so well known that it has been the subject of a dozen patents filed by international companies, obvious cases of biopiracy that have led to endless challenges in patent offices. For example, in September 1994, the American chemical company W.R. Grace, a competitor of Monsanto, secured a European patent for the use of neem oil as an insecticide, preventing Indian companies from marketing their products abroad except if they paid royalties to the multinational corporation, which was also flooding the country with chemical pesticides.

These were the chemical pesticides that caused the first wave of suicides among indebted cotton farmers in the late 1990s. The intensive use of synthetic insecticides produced a phenomenon well known to entomologists: the development of resistance by the insects to the products intended to combat them. The result was that to get rid of the insects, farmers had to increase doses and turn to increasingly toxic molecules, so much so that in India, where cotton covers only 5 percent of the land under cultivation, it alone accounts for 55 percent of the pesticides used.

The irony of the story is that Monsanto was perfectly capable of benefiting from the deadly spiral that its products had helped create and which, in conjunction with the fall in cotton prices (from $98.20 a ton in 1995 to $49.10 in 2001), had led to the death of thousands of small farmers. The company praised the virtues of Bt cotton as the ultimate panacea that would reduce or eliminate the need to spray for bollworms, as its Indian subsidiary’s website proclaims.

In 1993, Monsanto negotiated a Bt technology license agreement with the Maharashtra Hybrid Seeds Company (Mahyco), the largest seed company in India. Two years later, the Indian government authorized the importation of a Bt cotton variety grown in the United States (Cocker 312, containing the Cry1Ac gene) so that Mahyco technicians could crossbreed it with local hybrid varieties. In April 1998, Monsanto announced that it had acquired a 26 percent share in Mahyco and that it had set up a 50-50 joint venture with its Indian partner, Mahyco Monsanto Biotech (MMB), for the purpose of marketing future transgenic cotton seeds. At the same time, the Indian government authorized the company to conduct the first field trials of Bt cotton.

“This decision was made outside any legal framework,” said Vandana Shiva, whom I met in her offices at the Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology in New Delhi in December 2006. The holder of a Ph.D. in physics, this internationally known figure in the antiglobalization movement received the “alternative Nobel Prize” in 1993 for her service to ecology and her efforts against the control of Indian agriculture by multinational agrichemical corporations. “In 1999,” she told me, “my organization filed an appeal with the Supreme Court denouncing the illegality of the trials conducted by Mahyco Monsanto. In July 2000, although our petition had had not yet been considered, the trials were authorized on a larger scale, on forty sites spread over six states, but the results were never communicated, because we were told they were confidential. The Genetic Engineering Approval Committee had asked that tests be done on the food safety of Bt cotton seeds, used as fodder for cows and buffaloes, which thus might affect the quality of milk, as well as on cottonseed oil which is used for human consumption, but that was never done. In a few years, Monsanto had carried off a hijacking of Indian cotton with the complicity of government authorities, who opened the door to GMOs by sweeping away the principle of precaution that India had always upheld.”

“How was that possible?” I asked.

“Well, Monsanto did considerable lobbying. For example, in January 2001, an American delegation of judges and scientists very opportunely met Chief Justice A.S. Anand of the Supreme Court and vaunted the benefits of biotechnology at the very time the court was supposed to issue a decision on our appeal. The delegation, led by the Einstein Institute for Science, Health, and the Courts, offered to set up workshops to train judges on GMO questions. Monsanto also organized several trips to its St. Louis headquarters for Indian journalists, scientists, and judges. The press was also extensively used to propagate the good news. It’s appalling to see how many personalities are capable of stubbornly defending biotechnology when they obviously know nothing about it.”

It should be noted in passing that not only Indian personalities fell for Monsanto’s line. A company press release on July 3, 2002, reported with obvious satisfaction that a European delegation had gone on a tour of Chesterfield Village, the biotechnology research center in St. Louis. “The delegation of visitors represented government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, scientific institutions, farmers, consumers, and journalists from twelve countries that are involved in biotechnology and food safety,” according to the press release.

“Do you think there was also some corruption?” I asked.

“Well,” Shiva answered with a smile, searching for words, “I don’t have any proof, but I can’t exclude it. Look at what happened in Indonesia.”

On January 6, 2005, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) launched a two-pronged proceeding against Monsanto, accused of corruption in Indonesia. According to the SEC, whose findings can be consulted on the Web, Monsanto representatives in Jakarta had paid estimated bribes of $700,000 to 140 Indonesian government officials between 1997 and 2002 for them to favor the introduction of Bt cotton into the country. They had, for example, offered $374,000 to the wife of a senior official in the Agriculture Ministry for building a luxury house. These generous gifts, it was claimed, had been covered by fake invoices for pesticides. In addition, in 2002, Monsanto’s Asian subsidiary was said to have paid $50,000 to a senior official in the Environment Ministry for him to reverse a decree requiring an assessment of the environmental impact of Bt cotton before it was marketed. Far from denying these accusations, Monsanto signed an agreement with the SEC in April 2005 providing for the payment of a $1.5 million fine. “Monsanto accepts full responsibility for these improper activities, and we sincerely regret that people working on behalf of Monsanto engaged in such behavior.”