In his first week in office, President Trump and his legion of corporates and billionaires declared war on women by imposing global health restrictions on funding of NGOs that provide abortions; war on indigenous people by pledging to build the Keystone pipeline and reinstate the Dakota Access pipeline; war on the arts by threatening to end the NEA; war against women’s bodies by threatening to gut the DOJ’s Violence Against Women and defund Planned Parenthood; war on the earth by denying climate change, signing off on massive deregulations and hiring the head of Exxon as secretary of state; war on even our ability to dissent by declaring the press the opposition party. This is an all-out assault.

The Trump administration is asserting its power to undo years of social justice work, and is doing so with arrogance and aggression, and no ear for irony. Only a day after the women’s march where around five million people took to the streets across the world, it gutted funding for women’s health. On Holocaust Remembrance Day it barred Muslim refugees from seven countries from entering the US and announced the imminent building of a wall between the US and Mexico. The question we are confronted with every moment of every day of this new administration is what does a majority population do when our values, laws, rights, and humanity are being destroyed by a minority government that has total control of the executive, while the legislative branch exerts no meaningful check even as that power runs amok? How do people protect the marginalized populations under siege—or themselves? When every right and freedom is under attack, what kind of response is required? What do disempowered populations do with their rage and injury when they feel so utterly disregarded and attacked? What responsibilities do we have when we see a regime that has the potential to destroy this country and the world?

These are huge questions and I think this series could not arrive at a more important time.

The question of violence versus non-violence has been debated for years. Throughout history, we have seen state violence and individual violence arise—some are labeled as righteous and politically justified and others defined as terrorists or thugs. The unfolding of these narratives usually has to do with who is in power.

Around the world, women have been suffering political oppression and worse for years, but we do not expect them to be violent. We tell ourselves that women who take up guns are aberrations. We are terrified of women’s rage, their fierceness, and their righteousness, so we create narratives and projections that deny their power of agency and authority. We tell ourselves that they kill for their husbands, that they are merely pawns, used and misused in a men’s game. They don’t have their own politics. Not “real” politics. They get drawn into “bad” situations against their will. They don’t know what they’re doing. We frame these stories any number of ways, but make sure that militant women are never the central characters, never voicing and determining their own story. This is far easier than confronting the depth of female commitment, radicalism, and vision. How does a mother watch her baby starve or her daughter be raped by soldiers of mining companies occupying her land without retaliating? How does a women continue on when she herself has been raped and re-raped by soldiers in a war fought over her country’s resources? How do women not go insane when they witness the daily assault of corporations and their proxy militias on their land, their water, their children, their husbands, their sons?

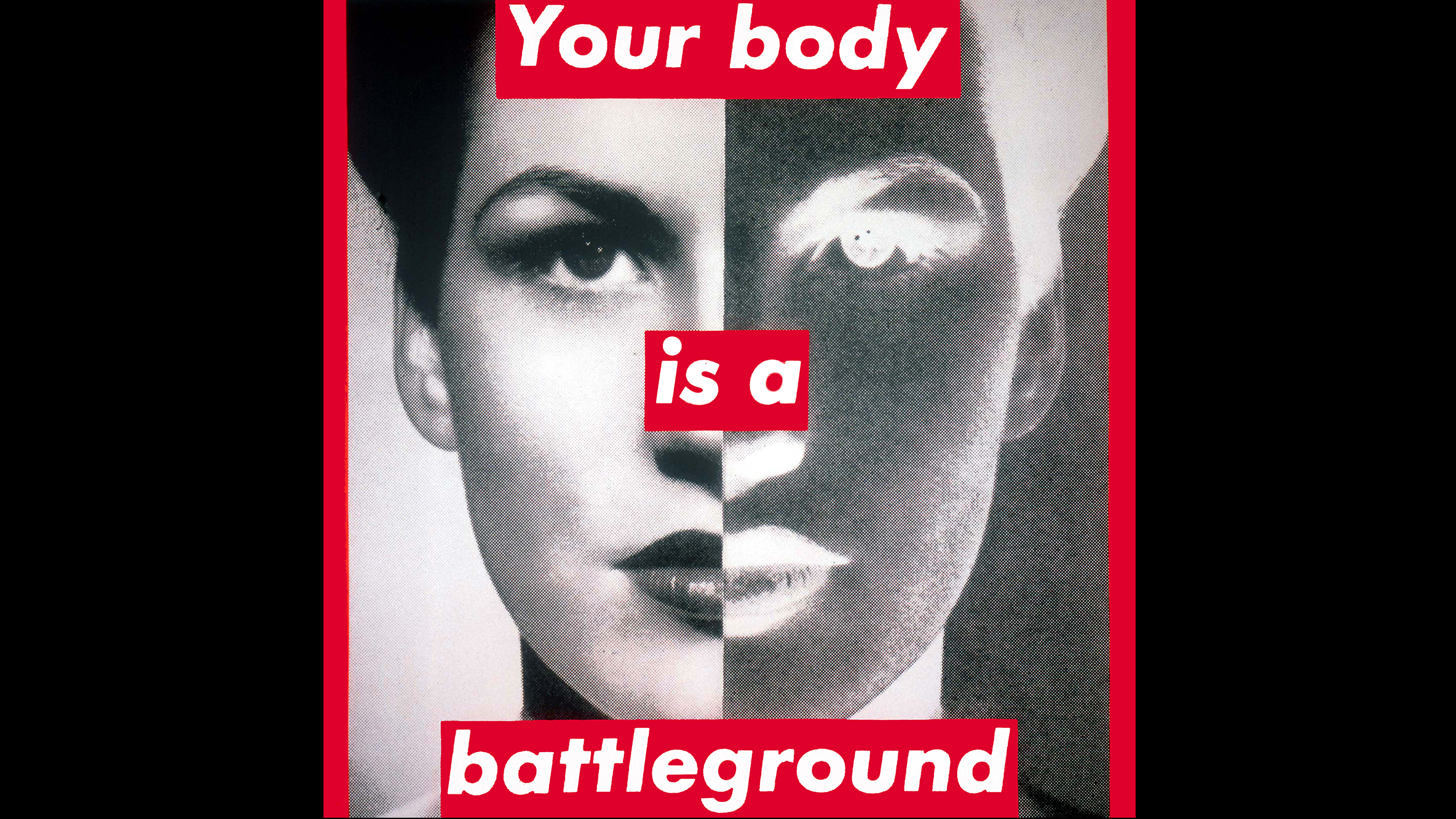

Women don’t even have the right to our own violent fantasies—let alone to the expression of those fantasies. We have been trained to suppress them as if to express them would reveal an alternative self buried deep below the sexist borders. We are trained to stuff our feelings, to be polite. To be peacemakers.

But there are women who break out of this mold. Isn’t crucial that we investigate what drives them to become militants, what pushes them over so many social and cultural borders? Can we brush aside accumulated clichés about women warriors enough to ask, and see: What if women who pick up guns are not lost, not pawns or followers, but political agents who are very clear in their purpose?

Through this series, writers do not seek to advocate violence, but to explore it. What can militant women teach us about our own rage, our own resistance, about expanding the borders of how we define female boldness and bravery? I spent years in a writing group at Bedford Hills Correctional Facility in New York, working with women who had been incarcerated for violent crimes. In listening to their histories of violence and oppression, it struck me that each of these women had acted out. For better or worse they had not remained passive in the face of inordinate cruelty, racism, sexual abuse, economic deprivation. I forced myself to really examine what it means for a woman to cross the line, to take power in her own hands, to refuse to be a victim. This examination means going beyond the simplistic judgment of right and wrong.

What is the function of women in movements for liberation? What does it mean for women to put their bodies on the line? On what basis can we judge women who live in the deepest state of oppression—who face morbid poverty, violence, displacement, rape, destruction of their homeland, imperialistic interventions—for taking up arms? We need to investigate what women fighters are thinking. What they are learning. It is very easy to have a knee-jerk reaction against violence when one lives with privilege and safety. Let us move beyond what is easy.

Some great writers have already done serious writing on the topic. When Arundhati Roy was accused of believing that non-violence was futile, she wrote in her seminal piece “Walking with the Comrades”:

Non-violence and in particularly, Gandhian non-violence, in some ways needs an audience. It’s a theater that needs an audience. But inside the forests there is no audience when a thousand police come and surround the forest village in the middle of the night, what are they to do? How are the hungry to go on a hunger strike? How are the people with no money to boycott taxes or foreign goods or do consumer boycotts? They have nothing. I do see the violence inside that forest as a ‘counter violence.’ As a ‘violence of resistance’…. I don’t think that there is any romance in it. However I’m not against romance. I do feel it’s incredible that these poor people are standing up against this mighty state.

I have interviewed women guerillas in the mountains of the Philippines and the indigenous Lumads fighting back against the mining corporations stealing and poisoning their lands, women in US prisons involved in the Black Liberation movement in the US imprisoned for violent acts. It is clear in joining militant movements that women escaped traditional oppressive gender role assignments in every society. Every woman I spoke to talked about rage, rage and helplessness in the face of state power. For them, becoming an armed militant was a way of expressing political outrage and not being rolled over by the neoliberal, racist, capitalist patriarchy. It was a way of keeping dignity and fighting for their families and land and traditions and life itself. It was a way of surviving.

What can we learn from women whose sense of injustice and desire for freedom led them to become militant revolutionaries? I don’t know about you, but I wake up every day in a state of rage, trying to hoist myself from a panicked pit of helplessness. For many across this country and the world, this rage and helplessness is not new. Marginalized communities do not see the Trump regime as an aberration but rather a continuation of what they have been suffering for a very long time. Now this horror has come for the more privileged, and the ever-mounting rage and helplessness is the direct link to the struggles and reality of women fighters around the world. It is critical we explore the stories of women who pick up guns, their histories, their oppressions, their journeys and experiences, so we may learn from their mistakes and victories. Now is the time to deepen our understanding of the sacrifice, commitment, determination, and dedication that make up their fierce resistance. And I think there is no better time to explore and understand female rage.