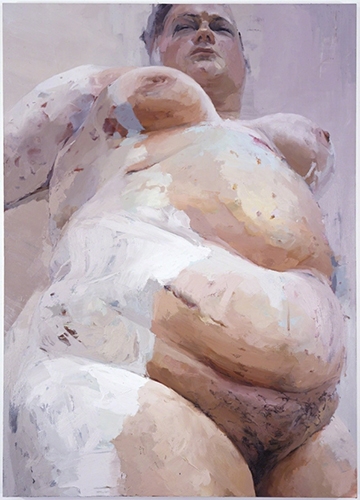

The body of Gigi Sauvageau was famous in our school, her long neck a question mark posed over pale shoulders, her enormous breasts bolstered by the rolls of her generous abdomen, that crevice dividing her navel, a shadow familiar to us all. Her pillow-sized pink thighs gleamed where they touched, and they touched everywhere. Because this was the early ’80s, the fact that Gigi shaved nothing was unremarkable aside from the fact that she was, consistently, brunette.

We were first-semester art students, most of us new to the city, awed by East Village grit, and determined to prove ourselves here. Armed with newsprint pads and tackle boxes stocked with charcoal crayons, razor blades, and kneaded erasers, our task was to render Gigi’s body in shades and shadows, or, as she challenged us from the posing platform, to capture “le moment” happening around Gigi Sauvageau.

Unlike other life drawing models, Gigi left her kimono untied during breaks, the silk fabric framing her jiggling front side as she circled the studio, eyeing our work, doling out either precise, cutting remarks, or praise delivered so sharply, the receiver would realize only hours later that a compliment had been hurled instead of a bomb.

“This one?” Gigi said the first time she paused behind my easel.

Our instructor, Iampolski, clarified: “Foster, you mean?”

“Foster?” Freeing a lock of dark hair from the perspiration beaded along her collarbone, Gigi considered my work. “Foster thinks he has talent,” she said and moved on.

Life modeling, we quickly learned, was Gigi Sauvageau’s life calling. Bragging of her popularity across a circuit of the city’s art schools and universities, she’d distribute business cards offering private sessions with the dubious invitation, “Because you never know when the mood’s gonna strike!” I still have mine, a faded blue cardstock with raised lettering: Gigi! Below that in script, Amor fati!, hovering above a street address in Williamsburg, then a seedy outpost in North Brooklyn.

Considering herself a medium of les postures, Gigi always began with a strange ceremony of closing her eyes and fluttering her fingers, claiming to “read the class” to determine which position we needed. Then, favoring reclined diagonals, she’d sink her hips to the platform, thighs anchoring her surprisingly lithe torso. “And now, we begin,” she’d sigh, allowing her body to relax, flesh following her spine’s lead like a tremulous afterthought.

Like most models, Gigi minded our time, transitioning us from one-minute warm-ups to ten-, fifteen-, and grueling thirty-minute poses. But instead of the typical oven timer, she used a round-faced alarm clock emblazoned with the brand name BIG BEN. Requiring constant rewinding and resetting, Big Ben was not an easy assistant.

“Benny,” she’d say, “is our little master.” Or, “Le temps!”—her lips exploding on the last syllable as we raced against Benny’s dreaded alarm.

Floyd Swesson, the only native New Yorker in our group, openly despised Gigi.

Iampolski watched Gigi’s classroom theatrics adoringly. The two clearly had some type of history, though none of us could envision what that history might be. Engaging in the conventional sexual pas de deux with Gigi would have posed an anatomical threat to Iampolski, whom we called, childishly, “the poor imp.” Added to this juvenile intrigue were glimpses of Iampolski’s tiny, devoted wife, who chauffeured him to school in a dying VW bug every Wednesday afternoon.

Floyd Swesson, the only native New Yorker in our group, openly despised Gigi. Where we saw shape, line, and shadow—a nude—he saw a naked overweight woman who spoke of herself in terms that violated what he knew.

One session, after Gigi called out insensitive Swesson for his overly aggressive, “masculine” lines, he retorted, “And what can you draw, Gigi?”

Opening her arms, her silky sleeves draping like wings, she announced, “Swesson! Gigi gives!”

Floyd Swesson worked maintenance in his uncle’s Williamsburg warehouse, the building where Gigi had lived for so many years, there was no way she could be legally extracted. He liked to remind us that her unit had no shower or tub. He even described the unheated communal toilet on her floor, no bigger than commode and sink, leaving us with the unfortunate visual of poor Gigi steering her generous rump inside the tight confines to do her business.

In the studio, he’d back up whenever Gigi neared him. “She stinks,” he liked to say.

The fluke of fate that forced Swesson to confront Gigi eye-to-ass (his term) in our classroom didn’t surprise him. He said we’d learn soon enough about the city’s predilections for toxic reunions and random run-ins. What troubled him more was Gigi Sauvageau’s sainted status at school. She was a con artist, he insisted, a Franco-phony poseur.

One assistant who ran study sessions for Fundamentals of Light countered Swesson’s disgust, insisting Gigi’s great mass was a “study in shadows,” her tendency to overheat our opportunity to master the “subtle essence of gleam.”

“She sweats, you mean,” Swesson said.

The dull drone who lectured us on Practical Business Skills for Artists suggested more convincingly that Gigi showed up on time, still charged what she did ten years ago, and, as she’d been around longer than many of the school’s instructors, might have some vague union measure covering her oft-rendered hide.

Instead of Gigi’s vulnerability, we saw only the complications her body created for us.

But by mid-semester, the upperclassmen had revealed to us the secret behind Gigi’s long reign: her proven ability to “see.” Once or twice a year, she’d filch a student’s painting from its easel and, within a few years, that student would encounter unexpected success—an inexplicable leap in technical skill, an unexpected invitation to a prominent group show, or perhaps a contract with a lucrative ad company. Gigi didn’t facilitate these successes. She didn’t even seem aware they had happened. But her eye had proven so consistent, no one confronted her for fear of breaking the spell, and soon enough, our class too, Floyd Swesson aside, joined the hopefuls vying for St. Gigi’s approval.

As soon as we believed, though, the change came. We should have noticed the signs. For God’s sake, we were there to learn how to see. But we were young, our faculties poor. Instead of Gigi’s vulnerability, we saw only the complications her body created for us—the elusive sheen of sweat across her abdomen, that intricate web of human netting between her thighs, the impossible quiver following the catch of her breath while we tried to pin down “le moment” as if it were a butterfly.

“She is dead, Foster.”

“Who’s dead?”

“Gigi!”

I’d arrived to the studio early for a conference Gigi had insisted Iampolski hold after detecting what she termed “le maybe” in my drawings during our previous studio session. Despite his handwritten cancellation sign, I’d entered. Iampolski had dimmed the lights and arranged our easels in a half-circle, each one holding a variation of Gigi’s Last Posture. Clutching his glasses in his trembling hands, Iampolski turned his eyes toward me and delivered the news. Her heart, of course.

“I’m sorry,” I said. Shamefully, I couldn’t help but notice how his makeshift shrine showcased my drawing of Gigi, the one she had blessed. Only my work captured not the lift but the lifting of her waist, the turning of her wrist, and the shape-shifting complexity of her stillness. I could see how her body had heightened my ability to make a figure be.

“She was my vision.” Iampolski’s voice trembled, failed even by the crutch of his Old World formality. “Her body was sacred to me.”

Fearing intimacy, the 19-year-old boy in me wanted out of the conversation, out of the studio, away from the embarrassment of an old man’s grief. After enduring a pause long enough to convey respect, I left poor Iampolski to his tears.

In the hall, a few students hovered by the sign on the door.

“Gigi is dead,” I told them.

“Class cancelled?”

I nodded.

A pretty girl who’d ignored me the entire semester shrugged and turned for the nearest exit. Another pair slapped a high-five and followed.

I remained, uncertain of where to go. I was disoriented by the uncomfortable nearness of death and bitterly disappointed the conference with Iampolski hadn’t taken place: she, with her proven eye, had selected me. On my way into school, I’d entertained the fantasy of Iampolski’s assurances that an artistic career would blossom effortlessly in front of me, that the world had overlooked my gifts. But, just as Gigi had steered Iampolski’s gaze toward me, she’d snatched it away.

Swesson appeared in the hallway. “Should have known the old crackpot would cancel,” he said after reading the sign. “You heard about Gigi?”

“Just found out.”

“Drama, of course,” Swesson said. “No other way out for Madam Gigi.”

Depressed over the unfulfilled promises I’d never received, I listened to Swesson’s sneer of a story. In Williamsburg, the whole building had to be evacuated after Gigi’s body was discovered, the other tenants forced to wait outside until the body was removed with enormous (his emphasis) difficulty. No next of kin. They’d just been allowed access into her unit that afternoon, his uncle hoping to confiscate valuables to recuperate lost rent.

Swesson shrugged. “Last chance. Wanna see le chateau Gigi?”

Numbly, I followed him to 14th Street and boarded the L train for Brooklyn and Bedford Avenue.

In Williamsburg, as Swesson led me down a side street toward the East River, a female voice taunted us with propositions from the velvety interior of a Lincoln Town Car. “Trolling for Hassids,” my unreliable narrator explained, tucking a cigarette into his mouth. The only other hint of humanity came from an after-hours car repair shop, its door rolled open to the street, the metallic ring of hammer to metal and manhood growing louder as we neared it. I glanced inside, but the thick-armed composer was hidden beneath an open hood.

Despite Swesson’s nonchalant swagger, I could see he was watching our backs. And that he could see I didn’t know how to.

We stepped into a darkness that smelled eerily of Gigi.

Near the East River, we came to a five-story brick warehouse with detailed moldings and masonry hinting at a prettier past. As Swesson navigated a series of locks on the front door, I imagined Gigi doing the same on similarly barren November nights, braced for the building’s cold concrete innards. Inside, we rushed beneath the high-ceilinged hallway and up five flights of stairs, chased by the echo of our own footsteps.

At the top, yellow police tape draped across a small, oddly placed door.

“They’ve already finished!” Swesson said disappointedly. He glanced around the desolate hallway. From below, the growl of a baritone rose so lonely and dreamlike, I couldn’t tell if it was a human voice or a sigh from the bowels of the building.

Swesson peeled back the tape, inserted another key from his ring, and we stepped into a darkness that smelled eerily of Gigi.

He turned on a light. A bare bulb tethered to the ceiling revealed a studio hardly bigger than a walk-in storage closet, which was perhaps the room’s intended function. A double sleeping bag and narrow mattress had been kicked to the side. An overworked hot pot and electric cooking burner sat on a shelf beside bags of Oreos and boxes of macaroni and cheese. A row of silky plus-sized kimonos hung from a clothesline strung across a corner, their feathery sleeves and hems agitated by our intrusion. In the center of the room, a balled-up white sports sock.

Through a large window, a spill of light across the black water, from Manhattan, intensified the bleakness of the shoreline in front of us.

I felt uncomfortable. We were spying on the shabby remains of a proud woman I hardly knew, a woman we’d laughed at, a woman who’d died alone in the very place we stood.

Unfettered by guilt, Swesson squatted in front of a safe, sizeable given the room’s dimensions. Its door hung open. “They already cleared it out,” he sighed.

“Maybe she didn’t have anything,” I said, wondering if we had the right to be in Gigi’s place, let alone the right to open things.

He pulled out a heavily beaded bra, a costume piece gone moldy under the armpits. Tossing aside the relic with disgust, he slid out a stack of stretched canvases that had been disregarded by the elder Swesson, who had gotten there first. As if cast again under Gigi’s spell, we considered each one. They seemed to be student works, varying in capability and stored in an arbitrary order. Gigi’s face and physique grew younger and older and younger again before us.

These were her chosen. Had she held on to them, certain of their future worth? Or had she hoarded them to feel a little less lonely?

Swesson slid out an elaborate frame wrapped in fabric. He pulled away the cloth, and we were faced with a childlike Gigi—naked on white fur—staring through a film of pigment and linseed. Vitality glowed beneath her pale skin. Her puckered lips shone open, ready to deliver. In those angled brushstrokes, I saw a far more advanced version of that same clarity her body had triggered in me.

“Iampolski?” Swesson noticed the signature first, that same scrawl that was scratched across the cancellation sign on the studio door. A dated invitation and a clipped newspaper review of a group show in a well-known gallery were in an envelope taped to the back of the frame.

Later, I’d learn Iampolski’s painting had caused a brief ripple in the local art scene, thanks to a charged but complimentary review that highlighted his history (dramatic escape from Soviet Russia, a promising stint at the Sorbonne) and a reporter’s follow-up interview with Gigi, who doled out eccentricity like catnip. The painting, tagged for purchase by a famous collector, might have made Iampolski’s career, but he’d refused to sell, insisting the work belonged to his muse Gigi.

This, I suspect now, fueled the intensity between them, that shared moment of vision and fame that never returned. But that night, Swesson and I were only two 19-year-old boys disturbed by the talent held hostage in an old man’s frustrations and terrified by his anonymity.

“Trash,” Swesson said decisively, and slid the portrait back into the safe, noting his uncle might get something for the frame.

A familiar tick caught my attention. I saw Big Ben beneath the kimonos.

Swesson followed my gaze. “Take it,” he said, grabbing a bag of Oreos to “make the blasted trip worthwhile.” He tore open the seal and started shoving cookies into his mouth before we even made it down the stairs.

Gigi’s shrouded body slid feet first and hung perpendicularly to the ground, arms strapped at the wrists, white sheets fluttering.

Back on the street, Swesson pointed toward the fifth-floor window and told me more about Gigi’s departure from the building she’d refused to leave for so many years. After her body was found, the oversized stretcher made exit through the small door impossible. A hook and ladder truck was called, enabling emergency workers to take the stretcher through the window, but one of the workers lost his footing, starting a cascade of mishandlings. As the evacuated tenants and a peck of Swessons watched from the walk, Gigi’s shrouded body slid feet first and hung perpendicularly to the ground, arms strapped at the wrists, white sheets fluttering.

The workers grasped at the stretcher’s frame, desperate to right their error, and Gigi’s enormous body rose like Jesus during the Ascension, that oldest of exits, impossible to outdo.

A gunshot near the pier punctuated the end of Swesson’s story. He threw the empty cookie bag onto the street, and we walked toward the subway, Big Ben ticking under my arm.

Iampolski managed to drag himself through December though cataracts hijacked his vision, the cruel side effect of some life-prolonging medication, and he retired at semester’s end. I finished my degree and, despite being the last to receive Madam Gigi’s approval, turned my eye toward that science of codified human fears and desires otherwise known as theology.

But to this day, whenever a beam of sunlight directs my eye to a graceful architectural detail above a city walk, or when I detect the moon-white smudge of a hen-of-the-woods mushroom clinging to a Central Park oak, or when I’m arrested by the gaze of a woman certain of her bodily powers amid the democratic swill of the subway—I pay tribute to Gigi. For she, as in the clichéd accounts of so many prophets, enabled the blind to see.