There is a wall papered with photographs whose corners overlap, a small television screen connected to headphones, and across the room, a darkened corner flickering with projected photos of New York City subway stations. From somewhere, “Copy ” by the Plastics is playing, and in another corner, a screen shows a fish-eyed Keith Haring bopping, his glasses streaking little paths of movement. It could have been an art space anywhere. It could have been 1980, before the artist’s work became wrist-watches and bed sheets and anything else that could hold three-color printing. But it is in fact 2012, and near Haring’s silent dance party is an iPad set up to record comments on the show, “”Keith Haring: 1978-1982,” March 16 to July 8th, 2012, at the Brooklyn Museum. In the afternoon on opening day there were ten comments, (“The exhibit is the best I’ve seen yet!”), that reflected the awing effect of seeing over one hundred Haring works on paper, over 150 of his “archival objects, ” and multiple videos.

The name Keith Haring—rockstar of the art world, New York City street artist, activist—has lost its status as a household name. Polling a random but relatively diverse group of people before I sat down to write this, only one knew who Haring was. I was surprised. I was not surprised, though, to find that all of those same people recognized his work. Even if the man behind the work has been obscured, Haring’s iconic primary colored or black lined figures—dogs, dolphins, babies, hearts, people, pyramids; radiating lines—are visually synonymous for most people with late 20th century art.

It’s hard to believe that someone like Keith Haring could ever fall into obscurity, but if there was anything that this well-curated show made me aware of, it was how seldom I’d seen Haring’s work in public spaces, or heard him talked about.

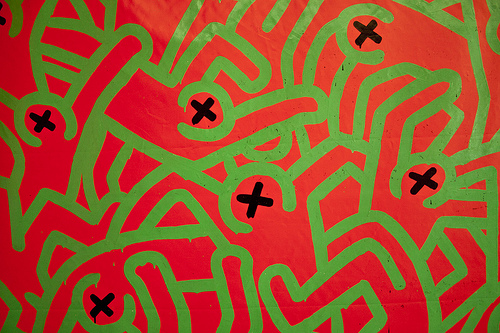

The Haring show at the Brooklyn Museum “…is the best I’ve seen yet! ” because it managed to capture the genius of someone prolific beyond his years, epic beyond his person, and delivered a window onto the depth of a body of work too easily pegged as commercial pop. The exhibit opens with a nine-foot figurative painting of a familiar Haring theme (“Untitled,” 1982) set against a red wall, on the fifth floor. Nearby is a row of Haring’s self-portrait polaroids—square-frame glasses, hangdog expression (or bored), a sometimes broken-out face. The exhibition, which the pamphlet says is “the first ever large-scale exploration, ” of Haring’s work, flows from one piece to another. New York Post assemblages (anti-Reagan propaganda), delicate line drawings on paper, graphite penises in a building-scape. A video, “Painting myself into a corner, ” (1979), shows Haring working rhythmically to Devo; red geometric forms, “Haring’s Alphabet ” (1978); and one after another of his Sumi ink paintings (mostly untitled), are staggered on walls, in cases, and on screens. Walk up to the paintings and see the way the strokes are laid confidently, like calligraphy, from one end to the other, solid in color without weak points in opacity, and precise white space between designs. Excerpts from Haring’s journals are printed here and there on the walls: “I am interested in making art to be experienced and explored by as many individuals as possible…”

And: “In painting, words are present in the form of images. Paintings can be poems if they are read as words instead of images.”

And: “The public needs art—and it is the responsibility of a ‘self-proclaimed artist’ to realize that the public needs art, and not to make bourgeois art for a few and ignore the masses.”

In a biopic on Haring’s life (Universe of Keith Haring, 2008) are stills of him in his native Pennsylvania, where he was raised on comics before heading to art school in New York City. In just seconds of film time, and what seems like moments in real life, Haring’s paintings are selling for thousands of dollars right out of his studio. Suddenly he is internationally known. When he is invited to Madonna’s wedding, Haring takes Andy Warhol as his plus-one.

In a New York City that was pumping out creativity and crime and movements that people tend to rhapsodize about, Haring’s art was stamped over the city streets and subways. It was like he channeled or digested the zeitgeist, keeping time with its furious pace. Then in 1990, at 31 years old, Haring died of AIDS.

Combined with the breadth of the work, the period music piped in, and the tablets available for attendees to draw, the Brooklyn Museum show is finely curated to deliver Haring’s motives. It’s hard to believe that someone like Keith Haring could ever fall into obscurity, but if there was anything that this well-curated show made me aware of, it was how seldom I’d seen Haring’s work in public spaces, or heard him talked about. There are existing Haring murals in New York City, which you can look up here, and Haring’s public bathroom mural at the LGBT Community Center was recently restored. But there seems to be no public trace of the thoughtful street artist now being displayed at the Brooklyn Museum. There is no sign of coupling figures, chalked on black paper, embracing beneath their own mistletoed energy in the subway these days. Haring’s work has been relegated to shops, the pop that made his art seem like Hallmark rather than grit, while the art that hangs in museums is mostly removed from the masses, re-appropriated by an art world that tends to his message in the only way it knows how.